“Ghost and Spirit,” the first major UK retrospective of Mike Kelley’s work, begins with “Personality Crisis” (1982). Three large signatures: first, “Mike Kelley” in prepubescent cursive, with looping L’s and curly K’s — it’s school-girl-cute; second, “Mike Kelley,” like runes carved into iron — it’s death-metal-hard-core; third, individual characters dissolve into one meandering snail trail, like a biro lost in a bag — it’s abject. Born into a Catholic family in the Detroit suburbs in 1954, Kelley’s identity crisis began at age fourteen. In 1968, he felt caught in limbo, “too young to be a real hippie, but just old enough to be eligible for the Vietnam draft.”1 His sisters were postwar, but he was Pop, that is, mediated and alienated. Kelley would spend the best part of his artistic career exploring how anchorless people forge ties with the world.

Adjacent is The Poltergeist (1979), texts and self-portraits inspired by early twentieth-century spirit photography. Kelley’s eyes roll back, cotton-wool ectoplasm streams from his nose. In this opening room (they’re arranged chronologically), the unruly secretion of line and spirit briefly formalizes into lemniscates and Venn diagrams — attempts to make sense of, externalize, and interrelate forces. In Monkey Island: Travelogue (1982–83), an all-seeing eye/I plots topographies with a proclivity for binaries (two buttocks, two hemispheres). One sketch resembles a dissected insect — opposing left and right wings, solitude and society, life and death. Another reads like a pirate’s map in search of “X,” dotted with landmarks — “mainland,” “whirlpool,” and “devil’s treasure.”

A couple of rooms later, more maps look for buried things. One is the blueprint for Educational Complex (1995), a tabletopmodel of past “haunts”— the institutions that shaped Kelley — reconstructed, unfaithfully, from memory. That model is too fragile to show, but we do see Sublevel (1998), an underground equivalent depicting the basement of CalArts, from which Kelley graduated in 1978. These reconstructions responded to the scientifically questionable 1990s notion of “repressed memory syndrome” which captured popular imagination. Sites Kelley could not recall — for whatever reason, many inferred abuse — were lined with pink crystal. Pink, because regardless of what’s outside, Kelley said, “it’s all pink inside.”2

Repressed memories were key to Freudian psychoanalysis, to which Kelley was not devote but nonetheless attracted by its absorption into popular culture. The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss considered Freud one of his mistresses along with geology and Marxism; each engaged in excavating hidden realities — an ID, a bedrock, a base — that explain visible orders. This Structuralist approach doesn’t subscribe to one school of thought over another but seeks out “the smallest common denominator of all thought,” the enduring structures (above/below) and the cultural variations they take (Freudianism, etc.). I see in Kelley an associate of Lévi-Strauss whose Structural study of myth Kelley near-perfectly relayed describing UFOs: “One can only retrieve archetypes, aspects of a collective unconscious that find their way into our perception as social clichés. […] A UFO is always a flying saucer. Such regularity of form is reminiscent of the standardized motifs in folk art.”3

Pink crystal walls give way to entire cities of crystal, frozen in belljars: the “Kandors” series (1999–2011). Studying comics, Kelley found that illustrations of Kandor — Superman’s hometown — were inconsistent, yet each filled gaps in the ekphrastic text with interpretive details. Kelley revels in memory’s malleability — its continuities and discontinuities. Recalling Gertrude Stein who, he observed, said “the same things over and over again” each time “slightly reworded,” Kelley was constantly re-constructing, re-enacting, and re-membering.4

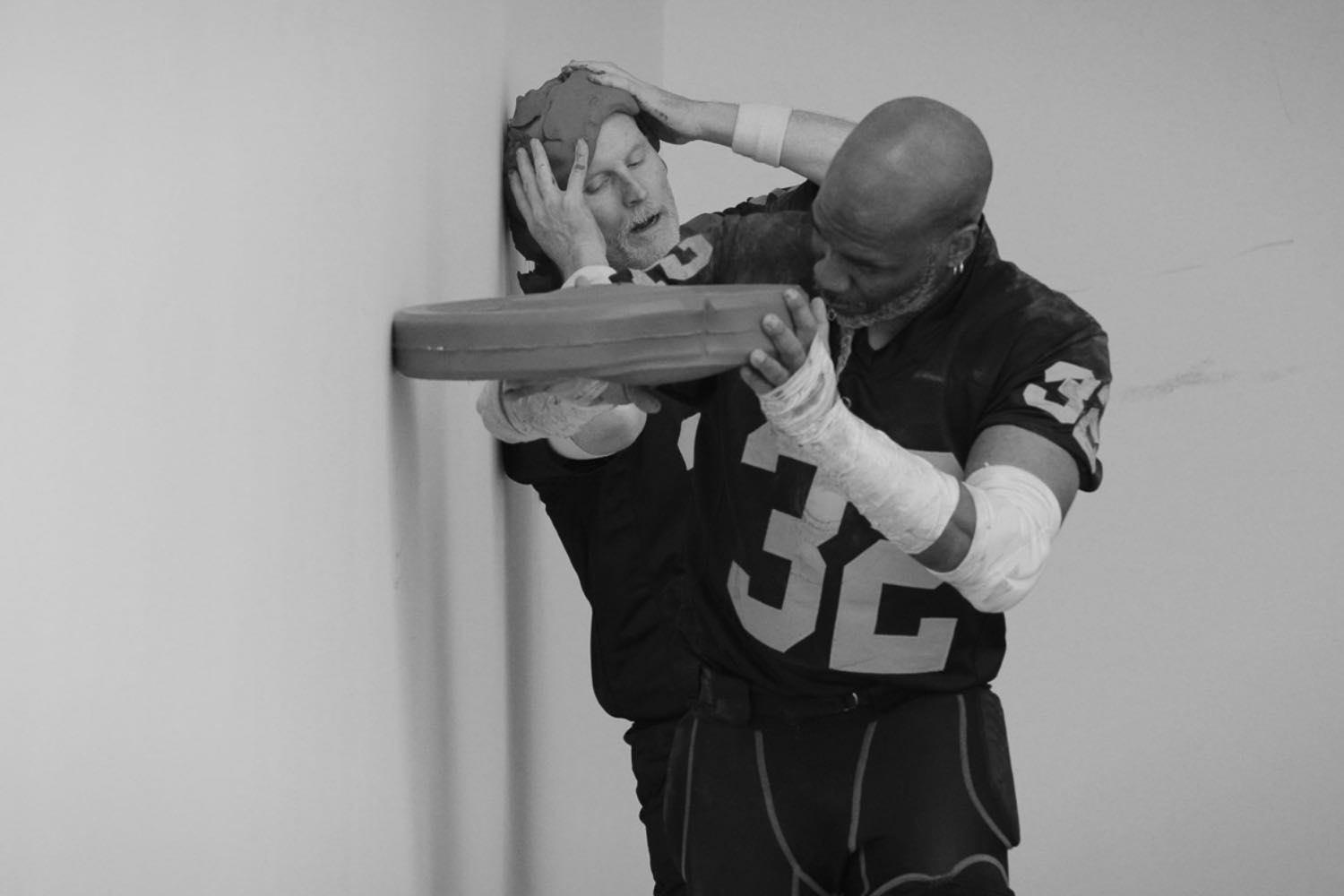

The penultimate room houses Day is Done (2005–06), a Gesamtkunstwerk of thirty-two videos, stills, sets, and props from “Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction” (2000–11), re-stagings of high-school pantos, nativities, and “dress-up-days.” It’s kitschy, campy brilliance, loaded with clashing genres and pop-cultural references. Kelley noted it’s “all about common cultural rituals,” more specifically, those occasions when institutions authorize carnivalesque behavior. “Fun Fridays” aren’t freedom, but these social phenomena bring us back to the question of what binds us to the world. Throughout Tate Modern’s “Ghost and Spirit” we see Kelley interrogate the relationship between belief and truth, cults and conspiracies, and the institutional upkeep of certain belief systems over others. Kelley shows us, from a distance but not without compassion, the clichés that sustain us.

If it feels like the show ends abruptly then it does. Kelley took his life at age fifty-six. Gus Van Sant, speaking about his novel Pink (1997), said “pink” is where “we go when we die, so it’s a lighter word for death.”5 For Kelley it was all pink inside, and perhaps, I think, pink is a lighter word for belief — what makes life worth living and what can make it so hard.