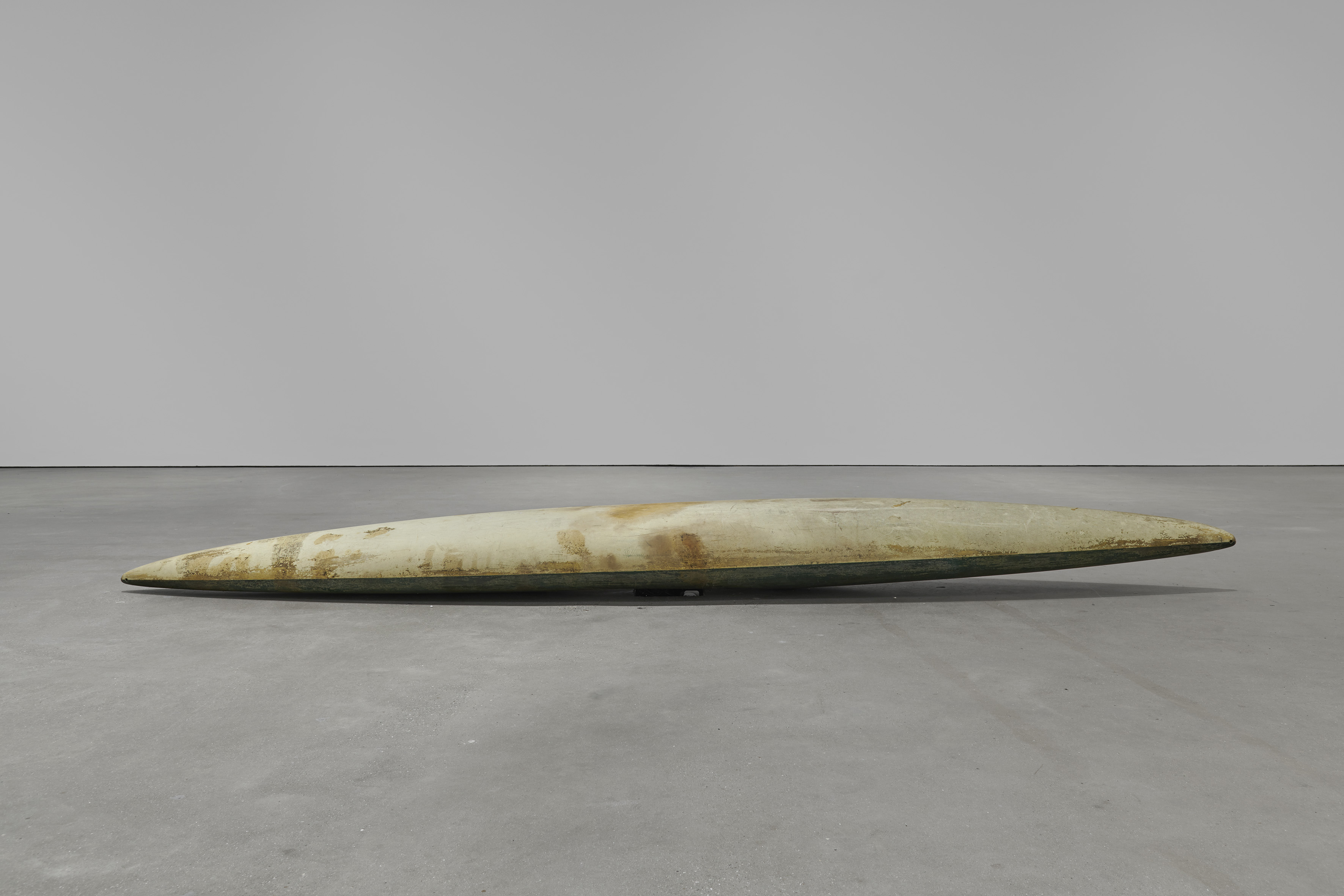

Writing in “The Spirit of Things,” the critic Barbara M. Benedict considers the rise of consumer society in relation to spiritualist movements in the nineteenth century. Writers of the time, Benedict observes, “represented spiritual meaning in the new idiom of the consumerist century: things.” In the societies of mass production that have developed over the rise — and faltering — of corporate globalization, the spirits Benedict speaks of in her essay still have not been exorcised; the object is a locus of spirit even when one object is designed to be materially indistinguishable from another. Michael E. Smith’s sculptural practice has concerned itself with the lives and histories of objects, and his new exhibition at Modern Art finds Smith in an elegiac register. A door mounted in the gallery’s information desk greets the visitor upon arrival. One passes through an open door to find a door that cannot be opened or closed. Smith’s cheap, mass-produced door may not lead one into a physical space as its numberless assembly-line cousins may do, but it leads to a kind of psychic space, an interior of a different sort. Smith, as a maker of installations, is intrinsically concerned with interiors that are distinguished as much by what they conceal as what they reveal. Two upturned canoes in the gallery’s downstairs space cannot help but evoke the beached carcasses of sea creatures — particularly as a whale recently was found washed up in the Thames nearby. Leaning over these objects, the viewer may discover the theremins hidden inside. The disruption of the electronic field produced by the instruments produces a sound that is sometimes thunderous, sometimes keening; a voice of invisible, ineffable forces.

A sense of unease pervades the show, but the exhibition is not without moments of humor. In the upstairs gallery one finds a sculpture made from basketballs and bedding trussed up by a steel rod into a kind of snowman scarecrow, and a backpack accented by this season’s must-have accessory: a catfish skeleton. Such objects may have been born in mass quantities, but Smith performs a kind of psychic inventory on them, creating space for the spirits they contain to address the culture that produced them.