At Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, songs by Meredith Monk lure viewers into the church nave. Large LED screens, suspended from wooden beams, play videos until a final piece that is only sound. A disembodied chant lingers in the room, which is austere for a church but ornate for an exhibition space. All this is part of “Calling,” a retrospective of the American artist’s work, who has been active since the 1960s when she staged performances at Judson Memorial Church in Downtown Manhattan. She exhibited at the Walker Art Center in 1998, and now, after two and a half decades, her work is in art spaces again, as Haus der Kunst in Munich and Oude Kerk in Amsterdam present a joint retrospective of her work.

Gathering Monk’s work for a museum show requires transformation. The 1942-born artist does not primarily make self-contained things that can easily be exhibited, much less in a white cube — which is presumably why both venues decided against such a setting.

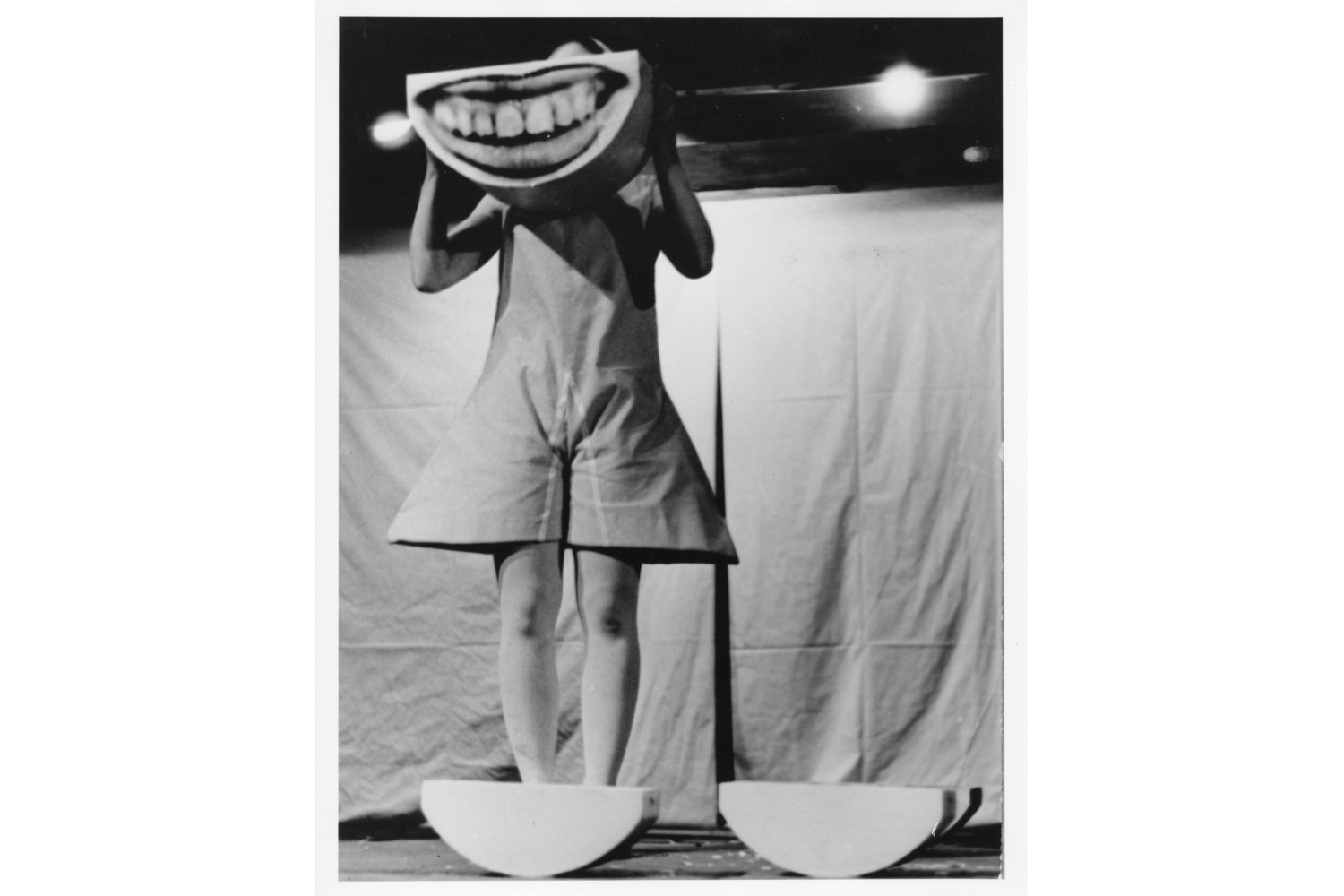

A case in point is 16 Millimeter Earrings (1966). The performance includes a film projection, recordings, and live singing. But what is it now — a documentation, a restaging? Haus der Kunst presents it in a nook of curtains. The net dress that Monk wore during the initial even, a table, and other objects are placed in front of the projection. In the mid-1960s, 16 Millimeter Earrings marked a turning point for Monk. For the first time she used all the media that came to define her work: film, dance, singing.

Monk continued with Juice (1969) at the Guggenheim Museum, New York. A group of performers, wearing red boots and dressed in all white like a cult, sang wordless chants on the spiral ramp of the museum while one of them arrived on horseback via Fifth Avenue. The second part took place in a small theater with fewer actors, and the final instalment was on view in the artist’s loft. In Munich and Amsterdam, the parts are presented side by side, almost like a diorama. Piles of red boots convey varying degrees of immediacy.

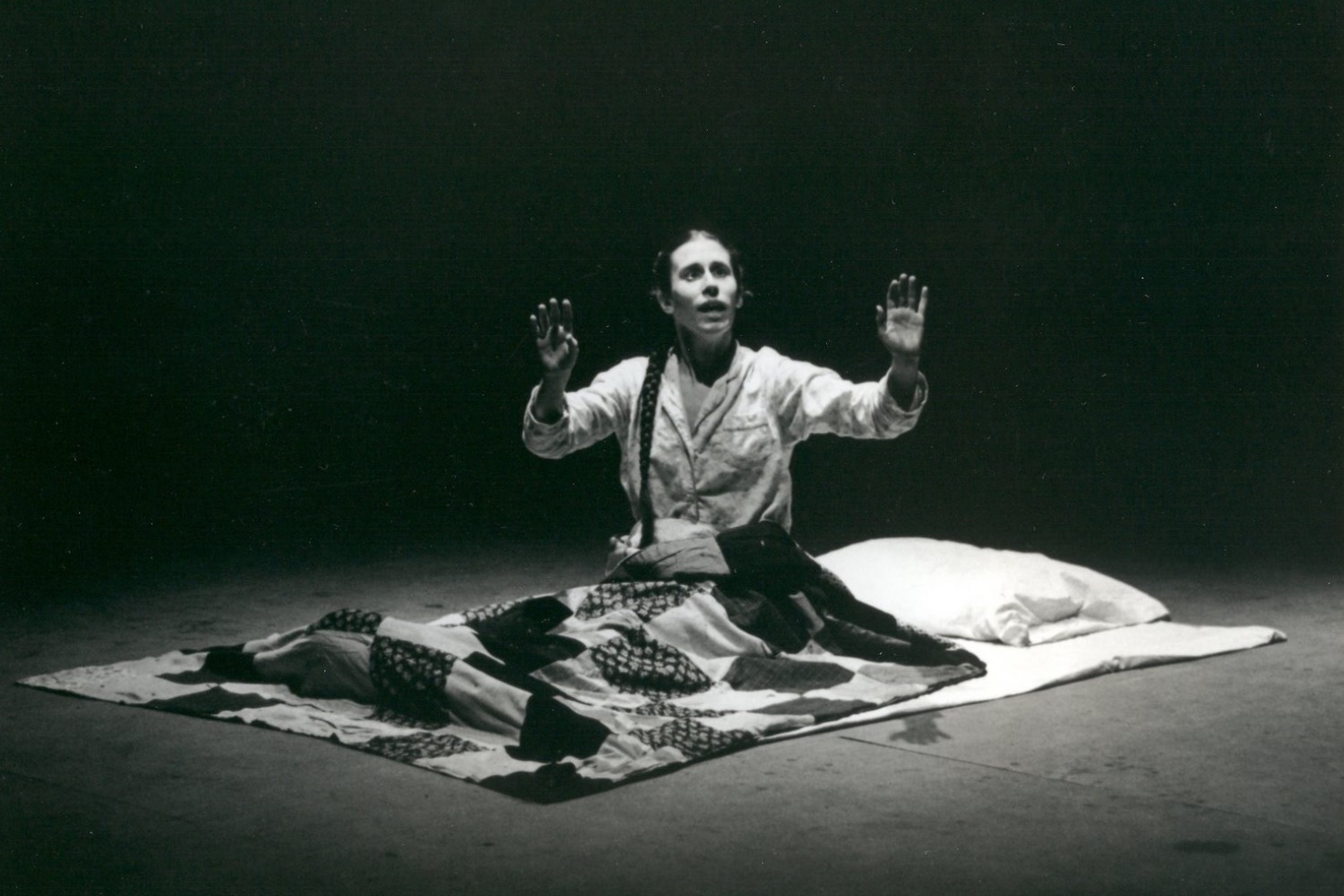

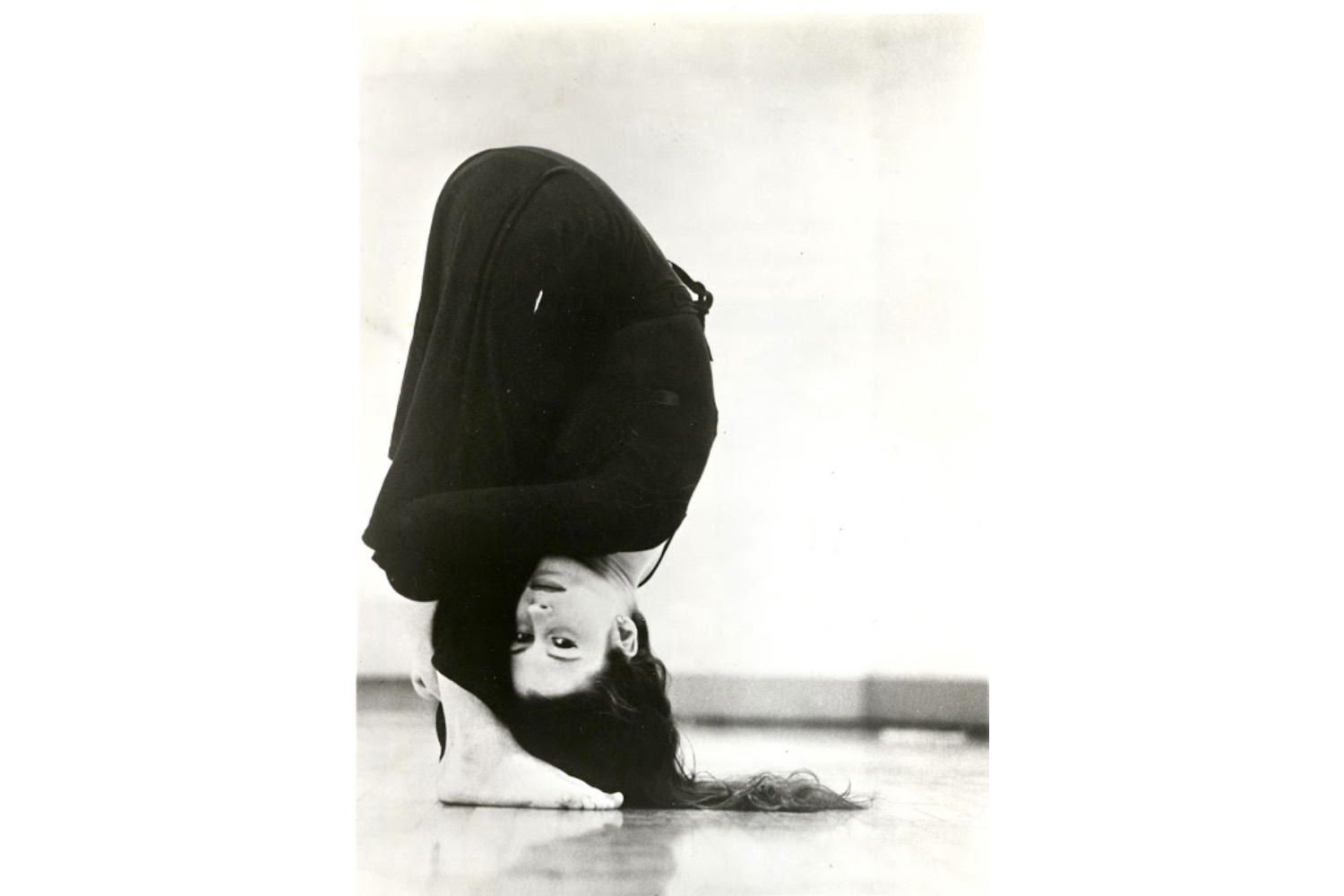

Possibly Monk’s disregard for fixed disciplines originated in her friendship with Black Mountain College teachers and alumni. Maybe it started much earlier. With an eye condition that complicates perception of space, as a child Monk was trained in eurythmics, in which bodily movements are used to express music. “The dancing voice. The voice as flexible as a spine,” Monk noted in 1976. She uses it like an instrument, with glottal sounds and shifts in pitch, and Dolmen Music (1981) is a prime example of the extended vocal technique she employs. It overlays polyphonic chants and percussive vocalizations that often collapse into indistinct chatter.

At Oude Kerk, Silver Lake with Dolmen Music (1981) fittingly occupies the choir, where chairs replicate the performance in which singers sat facing each other. Monk is interested in ritual, and the piece appears exclusive to the uninitiated. But Monk’s work is never hermetic. When it comes to her music, she is usually grouped with other minimalists; however, she steers clear of the deadpan cool of composers like Philip Glass. Her pieces are like “folk tunes of a culture she invented herself,” as critic Greg Sandow wrote in 1986, and they have a strong narrative pull.

Take Quarry (1977), which includes a film projection. Initially, it was shown as an opera, telling the story of a sick child who has visions about fascism and the Holocaust. The movie, consisting of carefully constructed tableaus, does not seem like the work of someone who has picked up the camera on a whim. Monk would follow it with longer film narratives, such as her carnivalesque film narratives, such as her carnivalesque 1988 feature Book of Days, reiterating the motif of the seer-child and visions of totalitarianism. She splices medieval Europe and 1980s New York, where AIDS echoes the plague. The film ends with a pogrom, like a premonition of modern antisemitism and racism.

In the interstice between the worlds of art and music, a shared language is often lacking. Perhaps this double retrospective also addresses the limits of curating an artist who works between film, sound, and dance. But the shows achieve a sharp focus on something else. In a performance of Songs of Ascension (2008), singers descend and ascend fantastical double helix shaped stairs, as if movement, space, and sound were the bare bones of narrative. As Monk wrote in the 1970s, the voice could be “a tool for discovering, activating, remembering, [and] demonstrating primordial/prelogical consciousness.”

“Possibly Monk’s disregard for fixed disciplines originated in her friendship with Black Mountain College teachers and alumni. Maybe it started much earlier. With an eye condition that complicates perception of space, as a child Monk was trained in eurythmics, in which bodily movements are used to express music.”