A collective endeavor of Greek antiquity — no less than eighty different artists worked on the frieze alone — the Parthenon was built between 447 BC and 438 BC under the orders of Pericles, following a democratic debate, and overseen by the sculptor Phidias. It measures ten meters high and approximately seventy meters long by thirty meters wide. As a temple, it was designed to house the colossal gold statue of Athena, along with the treasures of the Delos and the silver reserves of Athens. The precious metal could thus be melted down to make money to finance the war in the event of a Persian attack. This was the first time a temple had been built to celebrate both gods and men on equal footing; neither priestess nor cult resided there permanently. Converted into a Christian church in the Middle Ages and a mosque during the Renaissance, the Parthenon became, in modern times, the symbol of democracy and Western cultural supremacy. From the late eighteenth century onward, it served as the most influential architectural model for the design of secular buildings and institutions, both public and private (national assemblies, museums, banks, libraries, courthouses, academies, and universities), throughout the world.

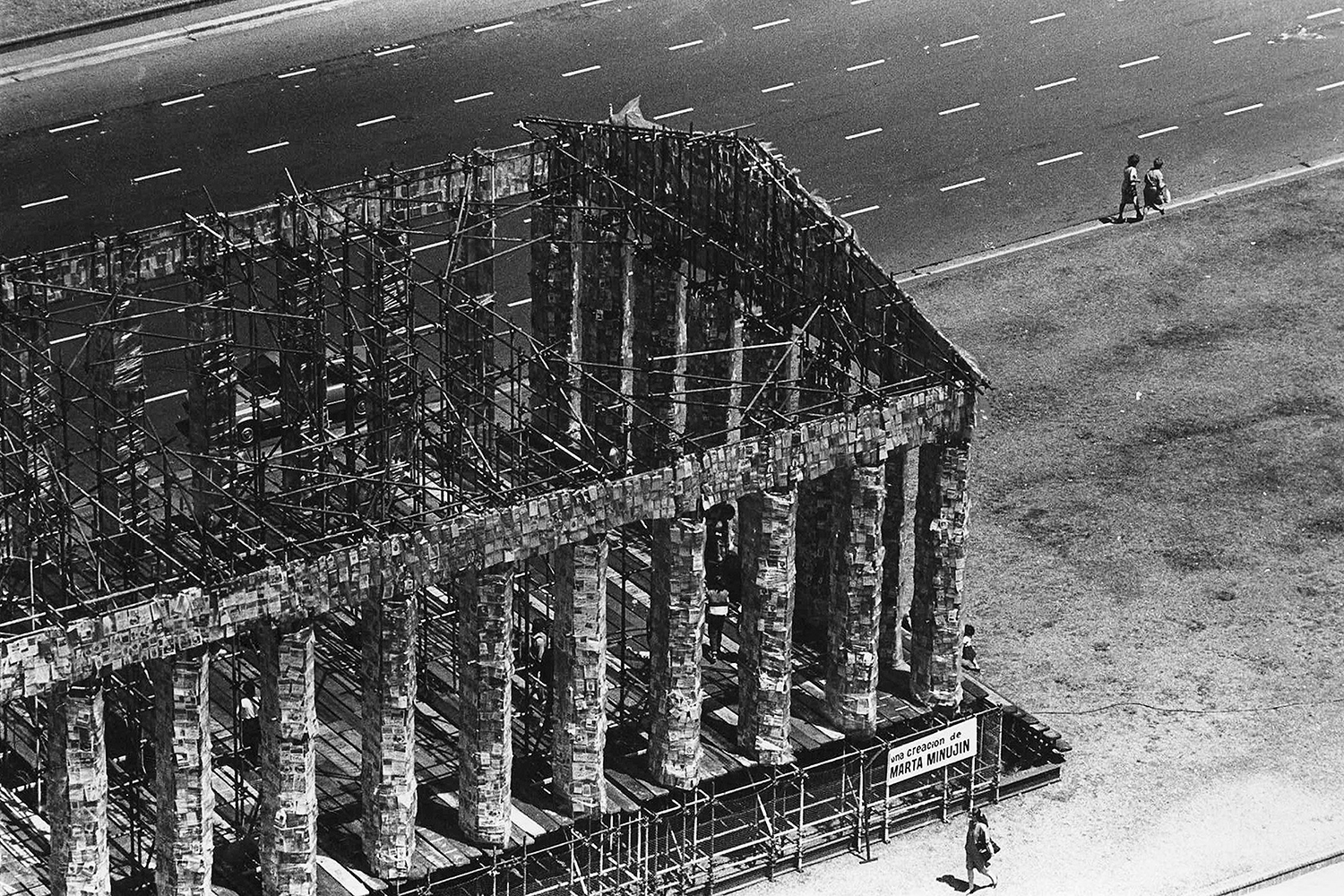

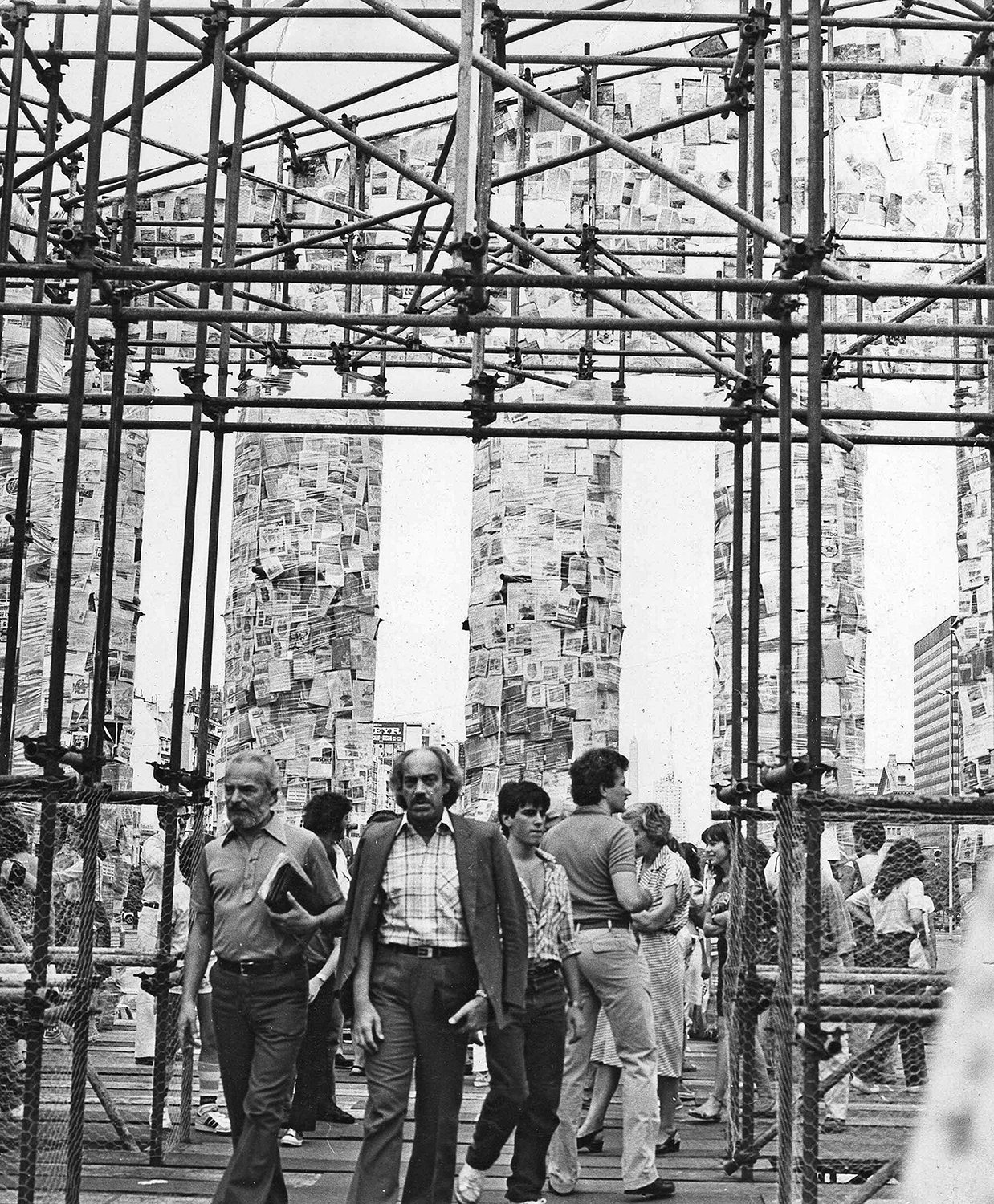

In 1983, the Argentinian artist Marta Minujín adopted the Parthenon as an aesthetic and political archetype of democracy, the latter corrupted in Argentina by a ruling “national Catholic” dictatorship at the time of the fall of the military junta. As part of her La Caída de los mitos universales (The Fall of Universal Myths), a series of large-scale public art projects, the artist’s aim was to collectively erect a replica of the Greek temple from books that had been banned during the military dictatorship.

The Parthenon of Books, Kassel, documenta 14, 2017

In presenting The Parthenon of Books as part of documenta 14 in Kassel, in 2017, Minujín did not merely intend to stage a retrospective exhibition of a work dating from 1983. Global power relations have changed since then: they no longer feature communist or right-wing military juntas, but rather those of a capitalist junta, one of the facets of which is embodied by the International Monetary Fund. For the artist to intervene in Kassel, Germany, meant updating her practice of subverting questions of originality by using the same archetype (in this case, the Parthenon, as she had already done on several occasions) in the context of a major international exhibition in 2017. As a collective exhibition, documenta 14 not only chose to address the stereotypes of ancient and contemporary Greece (the birth of Western democracy, the current financial and refugee crises) from the vantage point of the German city of Kassel, but as a curatorial project that upheld its aim by inhabiting Athens as its site of reference. In the critical exchange between Kassel and Athens, Germany and Greece, northern and southern Europe, Minujín chose to restage a presentation of the Greek Parthenon on the Friedrichsplatz, the city’s main square, at the center of a unified Germany transformed every five years into a “documenta Stadt.”

Historically, the gathering of banned books from around the world, with which Minujín erected her temporary architectural installation, took place at the site where the Nazi regime staged book burnings in the years leading up to the Second World War. The initial iteration of the Parthenon of Books in Buenos Aires, in 1983, was local in scope. In 2017, the gathering of books was carried out on an international scale and thus took into account the new balance of power imposed by neoliberal capitalism. This resulted in the first international scientific survey of banned books and the context in which they were outlawed. The survey was made possible in collaboration with students from the University of Kassel and published online.1 The Friedrichsplatz was the site of book burnings in 1933, organized and carried out by German students under the auspices of the National Socialist German Students’ League (NSDStB) as part of the “Action against the Un-German Spirit.” The propaganda campaign began on April 26, 1933, when blacklisted books were collected throughout Germany for burning. The Students’ action received the full support of bookstores and libraries. A specialist journal of the Union of German Librarians and a gazette of professionals in the German book industry published a list of and commentary on blacklisted books. Similar commentary was repeated by student representatives across the county as they threw books to the flames: “Against the overestimation of the instinctual drives that destroy the soul, for the nobility of the human soul! I throw the writings of Sigmund Freud to the flames.” Destruction by fire was not, however, the prerogative of the Nazis regime: 350,000 books were lost in the Allied bombing of the Fridericianum (which, at the time, served as a state library) in 1941 and 1943.

Historically, the gathering of banned books from around the world, with which Minujín erected her temporary architectural installation, took place at the site where the Nazi regime staged book burnings in the years leading up to the Second World War. The initial iteration of the Parthenon of Books in Buenos Aires, in 1983, was local in scope. In 2017, the gathering of books was carried out on an international scale and thus took into account the new balance of power imposed by neoliberal capitalism. This resulted in the first international scientific survey of banned books and the context in which they were outlawed. The survey was made possible in collaboration with students from the University of Kassel and published online.1 The Friedrichsplatz was the site of book burnings in 1933, organized and carried out by German students under the auspices of the National Socialist German Students’ League (NSDStB) as part of the “Action against the Un-German Spirit.” The propaganda campaign began on April 26, 1933, when blacklisted books were collected throughout Germany for burning. The Students’ action received the full support of bookstores and libraries. A specialist journal of the Union of German Librarians and a gazette of professionals in the German book industry published a list of and commentary on blacklisted books. Similar commentary was repeated by student representatives across the county as they threw books to the flames: “Against the overestimation of the instinctual drives that destroy the soul, for the nobility of the human soul! I throw the writings of Sigmund Freud to the flames.” Destruction by fire was not, however, the prerogative of the Nazis regime: 350,000 books were lost in the Allied bombing of the Fridericianum (which, at the time, served as a state library) in 1941 and 1943.

The Exhibition of the Production of Space

The Exhibition of the Production of Space

In Minujín’s work, the question of space is reflected in social relations, which only exist in and through space — their medium being essentially spatial. Her projects entail the kind of spatial practice that Henri Lefebvre sought to define by associating it with materiality, sensuality, use, and practice, as opposed to exchange, communication, and theory. For the artist, what defines a temporary counter-space is a collective texture or fabric that serves to reveal an ideology (economic or coercive) in action, present in public spaces. In his essay “Composition et parcours – Auguste Choisy et le pittoresque grec,” Jacques Lucan states that “For the Greeks […] construction and art are one and the same thing: form and structure are intimately linked. The ‘orders’ invented by the Greeks (Doric, Ionian, Corinthian) are the structure itself; the notion of ‘order’ contains that of structure, so that external appearance and internal composition (structure) in Greek buildings are indistinguishable: the first contains and reveals the second.”2 Minujín’s use of the Greek temple, in 1983, or again in 2017, is not merely symbolic as has been suggested, nor does it function in the sense that the Romans understood in their time: “The Romans saw in the orders they took from the Greeks only a decoration that could be removed, eliminated, transferred, or replaced by something else.”3 Minujín’s decision to use recyclable scaffolding as a cheap material to erect her Greek temple complies with a “spatio-analysis,” in Lefebvre’s sense, in that it both serves to problematize the context in which it is installed and, above all, aims at a particular practice — the exhibition of the production of space. The production of space, as Lefebvre developed it, encompasses architecture in its relation to social space and those who participate in it. Minujín’s intervention in public space, which extends over time without conforming to the opening and closing dates of an official event or its mode of paid access, embodies qualities that resemble those championed by a number of contemporary architects, in that it takes place via a collective endeavor that both reveals and conceals the urban structure.

The generative schemas of the New-Territories (S/he) agency under the direction of François Roche, for example, use VIABs (construction machinery) that are integrated into the building itself in order to generate the reticular structure of the building’s construction. VIABs are comparable to the cranes present on the site of the Parthenon in Kassel, where they served as moving organs suturing the skin of banned books covering the peripteral colonnade. In the case of Olzweg,4for example, the name given to the VIAB used by the New-Territories agency for an uncompleted museum project for the FRAC Centre in France, from 2006: to construct the building, a crane was designed to insert household glass bottles into the building’s facade, the bottles being provided, as a community service, by the recycling industry from the region where the museum is located. The building’s construction was to take place over a ten-year period in order to develop a long-term exchange with the building’s users. In the case of Minujín’s Parthenon of Books, the physical book, which is today often considered obsolete and anachronistic, conserves, in a paradoxical way, an anthropomorphic quality, in that, as a material object — a parallelepiped — in the human field of vision, it is, at the same time, the mental projection of a space or fiction. Yet, transformed into a physical building block, the book underscores our attachment in thought to the phenomenal realm of space as Henri Lefebvre astutely describes it in his The Production of Space: “The whole of (social) space proceeds from the body, even though it so metamorphoses the body that it may forget it altogether — even though it may separate itself so radically from the body as to kill it. The genesis of a far-away order can be accounted for only on the basis of the order that is nearest to us — namely, the order of the body.”5

Figure-Ground

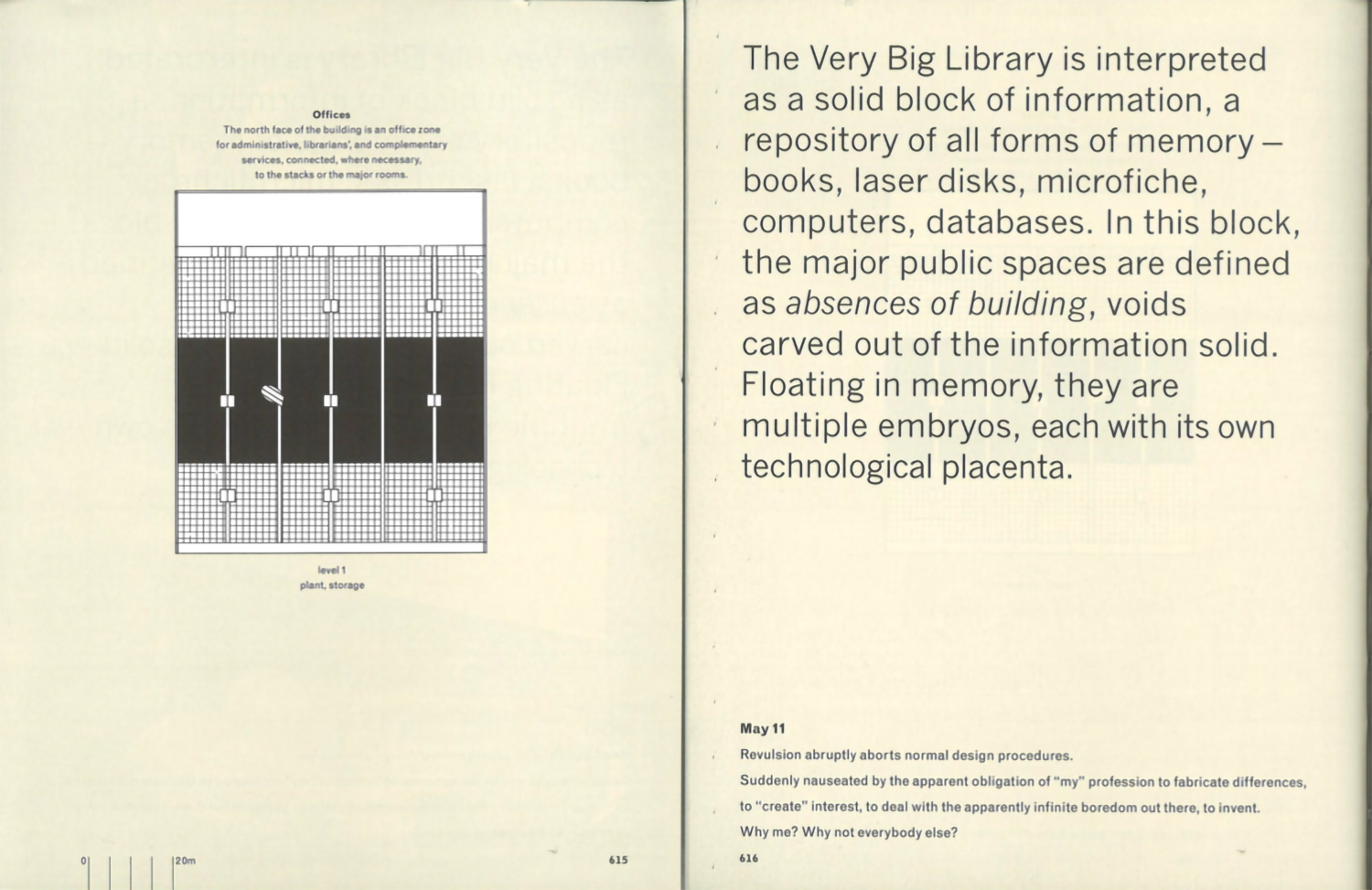

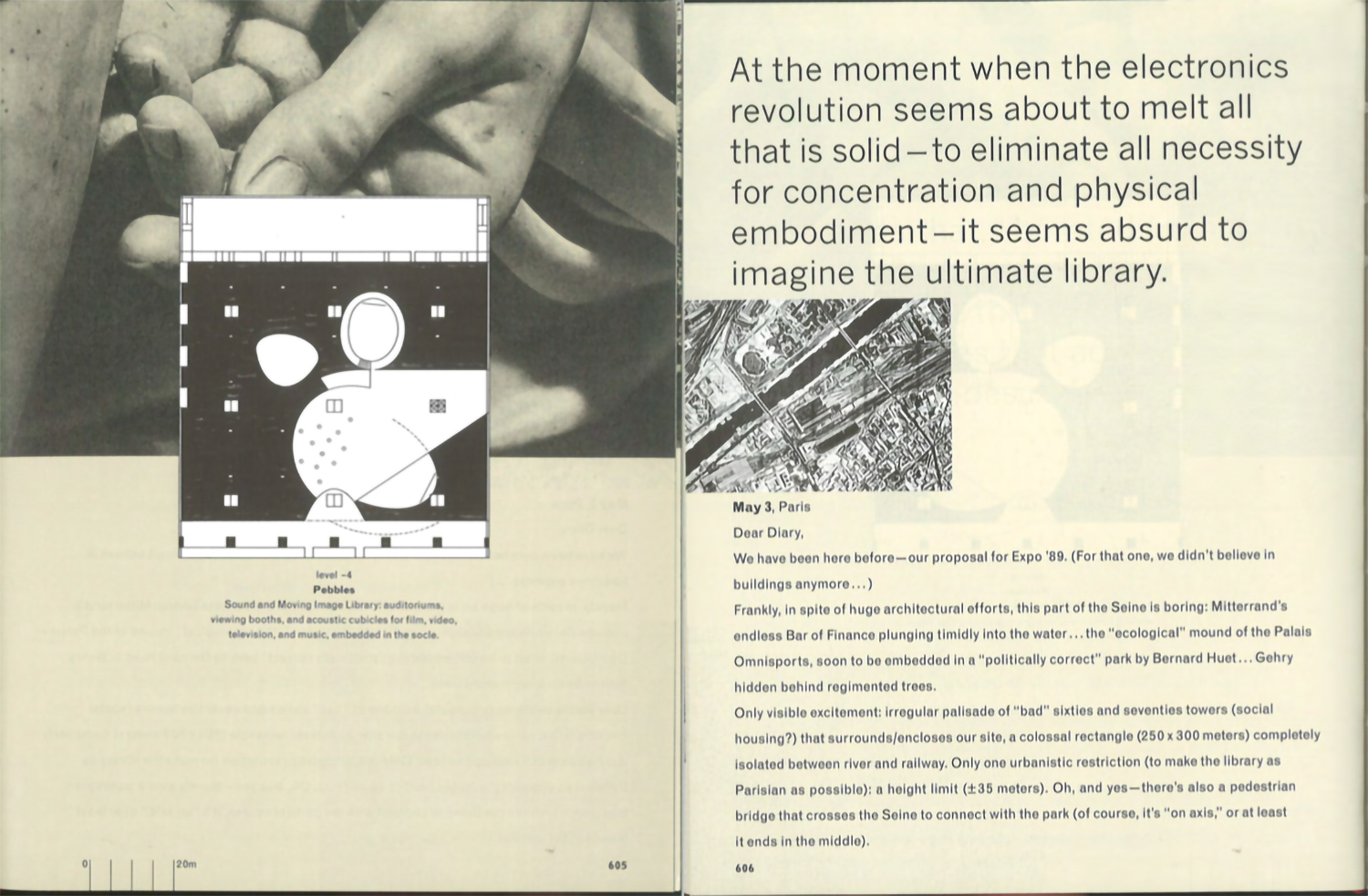

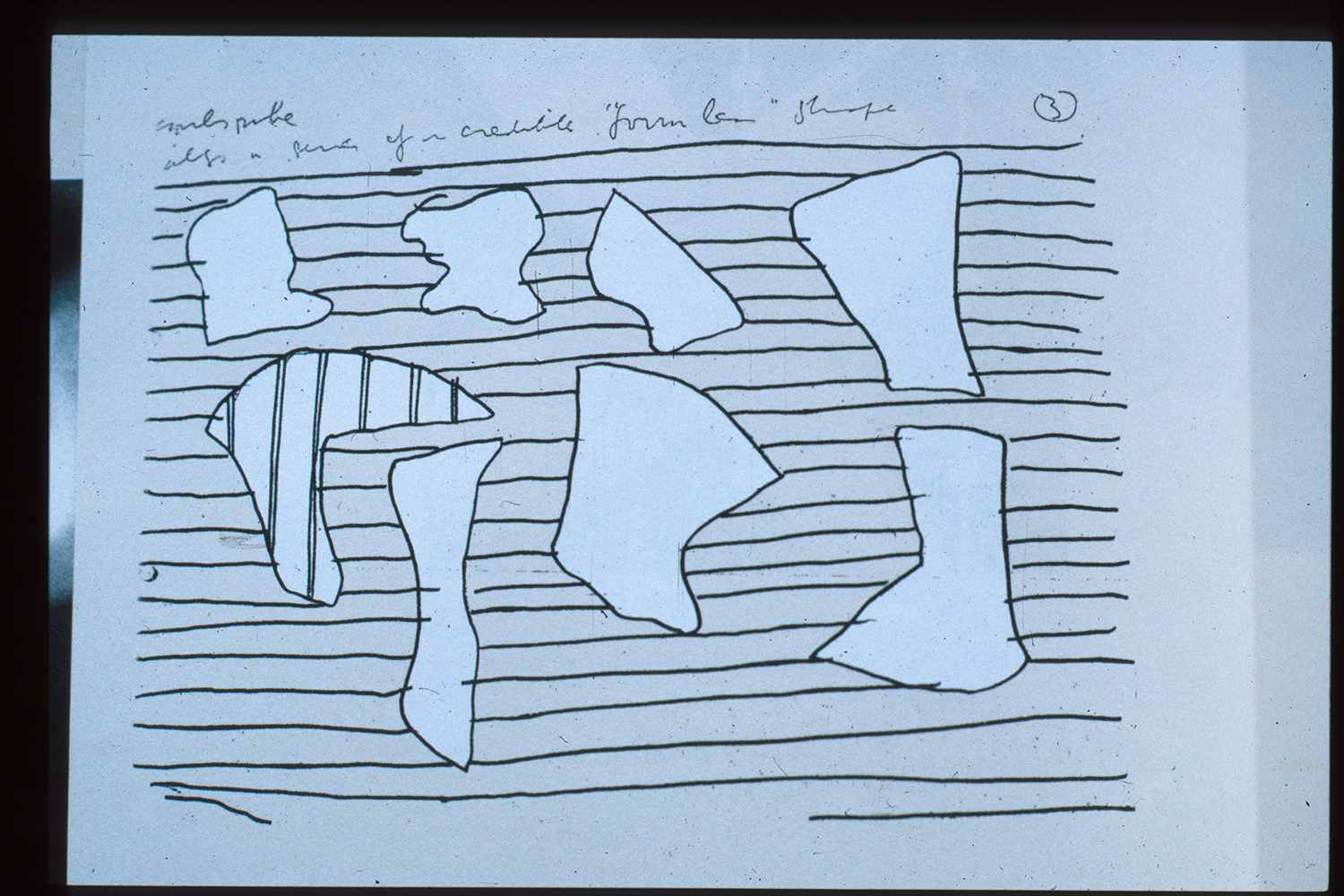

The banned book evokes a supplementary dimension that further enriched the Parthenon of Books as it was presented at documenta 14 in Kassel: the sign of an absence, a void, which paradoxically appeared as a shimmering brick demarcating a collective space. In 1987, another contemporary architect, Rem Koolhaas, developed a patent for his Strategy of the Void. For Koolhaas, only the “void” can be protected: “the last subject where certainty is still plausible.”6 He applied the principle of the void to his competition entry for the French National Library in 1989. A series of excavated voids, empty spaces that receive the public: “The library is envisioned as a solid block of information” in which “the major public spaces are defined as absence of building, voids carved out of the mass of information.” Minujín’s Parthenon of Books and Koolhaas’s project for the French National Library both “reverse the figure-ground relation — treating the void and thus the ground as a figure.”7 In 1989, Koolhaas envisioned on paper the production of space generated by a building’s public and users; something which Minujín was able to put to the test by making it a reality with her Parthenon of Books, first in 1983, and again in 2017.

Minujín’s spatial practice is socially based. The Parthenon of Books is ultimately the living construction of social and cultural relations, a site where a population could come together around her ephemeral architecture for a certain period in time and then disperse. Yet, the Parthenon of Books, as a collective endeavor, continues to exist, in a fragmented and dispersed state. The books have since been redistributed to visitors at the end of documenta 14 in Kassel, and henceforth line the bookshelves of public libraries and private homes across the globe. Such a collective momentum was instigated by an artist who does not hesitate to employ stereotypes. For example, her Perfume Operation from 1987, a transparent sculpture for which perfume was diffused along the main avenues in the center of Buenos Aires. Minujín’s exaltation is that of the intoxicating odors, noise, and warmth of urban reality — the air we breathe and share.

(Translation from French by Dean Inkster)