The environmental catastrophe that is currently unfolding before our eyes has a single culprit at its source — the human being. Of course, there are compounding and complicating factors, and, yes, as any elementary school science book will tell you, the earth has undergone previous cycles of warming and cooling, entire animal species have been wiped from the planet before, and fluctuations of greenhouses gases predated the invention of the automobile. But it is a fact that too much carbon into the atmosphere, put there by human beings, is the root cause of the climate changes presently observed, from warming temperatures and intensifying weather patterns to acidifying oceans and waning biodiversity, all of which are worsening at exponential rates.

New York–based artist Mark Dion has been witness to these and other ecological changes, and has centered his multidisciplinary art practice on them since the 1980s. He is often grouped with other contemporary artists invested in ecological issues, but unlike many of their activist-oriented activities seeking to expose the destruction, catalogue the environment, or translate scientific data in order to sound the alarm on climate change, Dion has approached the issue more holistically using the multifaceted vehicle of art. “Science is very good at telling us how things work and what things are, but art can put those facts into a context, which is social, historical, and even subjective,” states Dion. “Science tells us what things are, but art can express how we as a society and as individuals feel about that. This is far from an uncomplicated form of communication; it can express ambiance and contradictions, melancholy, and a range of very sophisticated human experiences.”1

Dion recognizes that humanity’s lack of care for the environment is not an issue of missing information — we have more than enough — but rather of will. And how do you change human will? Perhaps by exploring how things are learned, collected, represented, historicized, memorialized, and ultimately experienced and felt. The natural world is a primary arena for the expression of power and ideology. What, indeed, is more freighted than the placement of “man” at the top of animal hierarchies, the extraction of natural resources from the global South, and the idolization of certain species, like panda or polar bears, over others that are more important ecologically, like plankton or bees? If we understood how our knowledge and experiences of nature form (or, are formed), could we begin to reform them? Dion’s work offers us a vast mirror reflecting our own participation in the construction, and destruction, of the culture of nature and the nature of culture.

The relations between species, including humans, have long interested Dion. In 1992, he completed a series of early sculptures whose title, Concrete Jungle, refers to the dense and overlapping ecosystems present in urban environments. In Concrete Jungle (The Mammals), cats, rats, and cockroaches commune amid human refuse. This work and a number of sculptures that followed present what biologists call “r-selected” or opportunistic species — persistently adaptable creatures, like the German cockroach, starling, or zebra mussel, that have thrived as human civilization has expanded, in part by feeding on its waste. These species interest Dion for illustrating how “the whole idea of nature as something separate from human experience is a lie,” as he and his fellow artist and friend Alexis Rockman provocatively write in their book Concrete Jungle.2 Citing dioramas of pristine landscapes in natural history museums as a source of this fiction, Dion has undertaken a series of revisionist diorama works in which “culture was at the center of nature.”3

In Landfill, 1999–2000, pollution is the star of the staged scene. Black substance oozes from toppled barrels, and a dead tree rises from a dune made of garbage. When completing this sculpture for the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, Dion commented: “Here, there’s nothing that’s not been affected and exploited by humankind. I’m replacing the organic, natural base of the food pyramid with a cultural base, consisting of things that have gone through the process of human consumption.”4 Within this degraded landscape, mice, rats, and gulls scavenge to survive: their picking at products made of animal parts, adorned with animal logos, or intended for domestic pets completes an ecological circle. The background, exquisitely painted in traditional diorama style, depicts only human intrusions on the land: a dumpster, a factory, and the silhouette of a distant city. Finally, the elaborate scene is set within a standard four-by-eight plywood shipping container on casters, associating it with the circulation of commodity capitalism. Dion’s sculptures highlight human impact on the earth and other animal species through the naturalized mode of the diorama, inviting scrutiny not only of the heaped trash but also of the fiction of a landscape separate from human beings. Concrete Jungle, Landfill, and numerous other sculptures by Dion highlight the intersecting spheres of the human, animal, plant, and cultural, revealing these to be deeply interdependent.

In the early 2000s, Dion undertook a number of interactive, public sculptures inspired by the passions of botanists or birdwatchers, and infused with a sense of history, humor, and activism. South Florida Wildlife Rescue Unit, 2006, was inspired by botanists at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Miami, who told Dion stories of trespassing on land about to be developed in order to collect endangered plants and transplant them to safe locales, thereby “rescuing” wildlife. The yellow truck sculpture that dominates the installation, a fictional “unit” intended to carry out this work, embodies attributes present in many of Dion’s sculptures of the period. It is foremost a “mobile laboratory,” complete with all the necessary tools and equipment with which to undertake the delicate work of plant removal and the rapid retreat required to avoid reprisal. Its side opens up to provide a large window through which interested individuals outside the unit can interact with those specialists inside. Dion also designed an official seal and uniforms for the “wildlife rescuer,” giving a persona to the botanist-cum-activist vision. But how exactly do we demarcate “wild” from “cultivated”? Isn’t rescuing wildlife a self-defeating endeavor? Such public sculptures, including related works like Mobile Gull Appreciation Unit, 2008, and Buffalo Bayou Invasive Plant Eradication Unit, 2011, reflect the roles that we as humans assume, the tools we use, the judgments we pass, and the behavior we inhabit in interacting with the natural world.

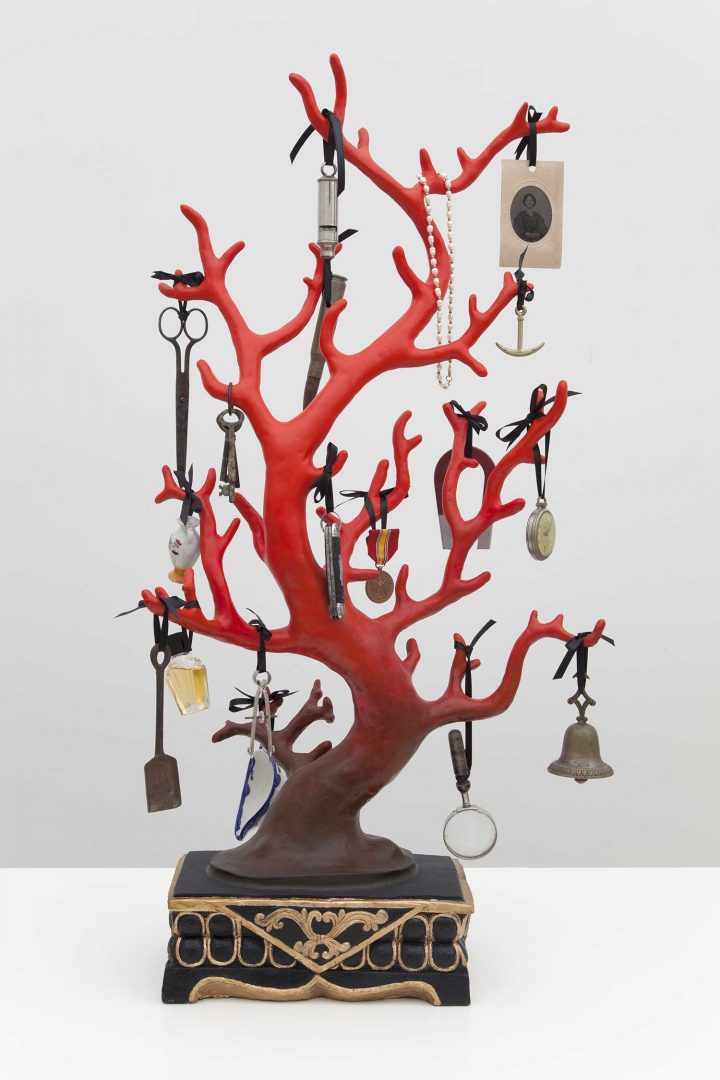

Dion is perhaps best known for his cabinets, inspired by the Renaissance Wunderkammer, especially their impulse to categorize and display collections amassed while traveling, foundational to the modern museum. He has led numerous expeditions of his own to sites and digs — including on the banks of the Thames River, in abandoned lots of New England, and on the construction site of the Museum of Modern Art in New York — to discover materials for his cabinets. In 2013, he joined a bona fide scientific expedition to the northern Pacific Ocean to study the massive accumulation of plastic in the oceans with a group of oceanographers, biologists, fellow artists, and others. Plastic detritus, some of it microscopic and some of it forming patches the size of the continental US, is altering ocean ecosystems, killing marine life, and leaching toxins. The trip ended with a cleanup of Hallo Bay in Katami National Park in southwest Alaska. Along a four-mile stretch of beach, participants collected an estimated four tons of garbage, from which Dion selected the objects that form his sculpture Cabinet of Marine Debris, 2014. Within a coolly gray cabinet, Dion organized the debris by type and size to create a stunning chromatic array. The sculpture is beautiful and awe-inspiring. People linger to enjoy and look closely at its contents, much like taking in the sea and landscapes along the Alaskan coast. The colorful buoys and fishing nets acknowledge and implicate the fishing industry while the plastic bottles and caps elicit the familiar domestic milieu. It is a beautiful and harrowing display that connects individuals and households to a global ecological epidemic that is literally strangling the plant and animal life of our oceans.

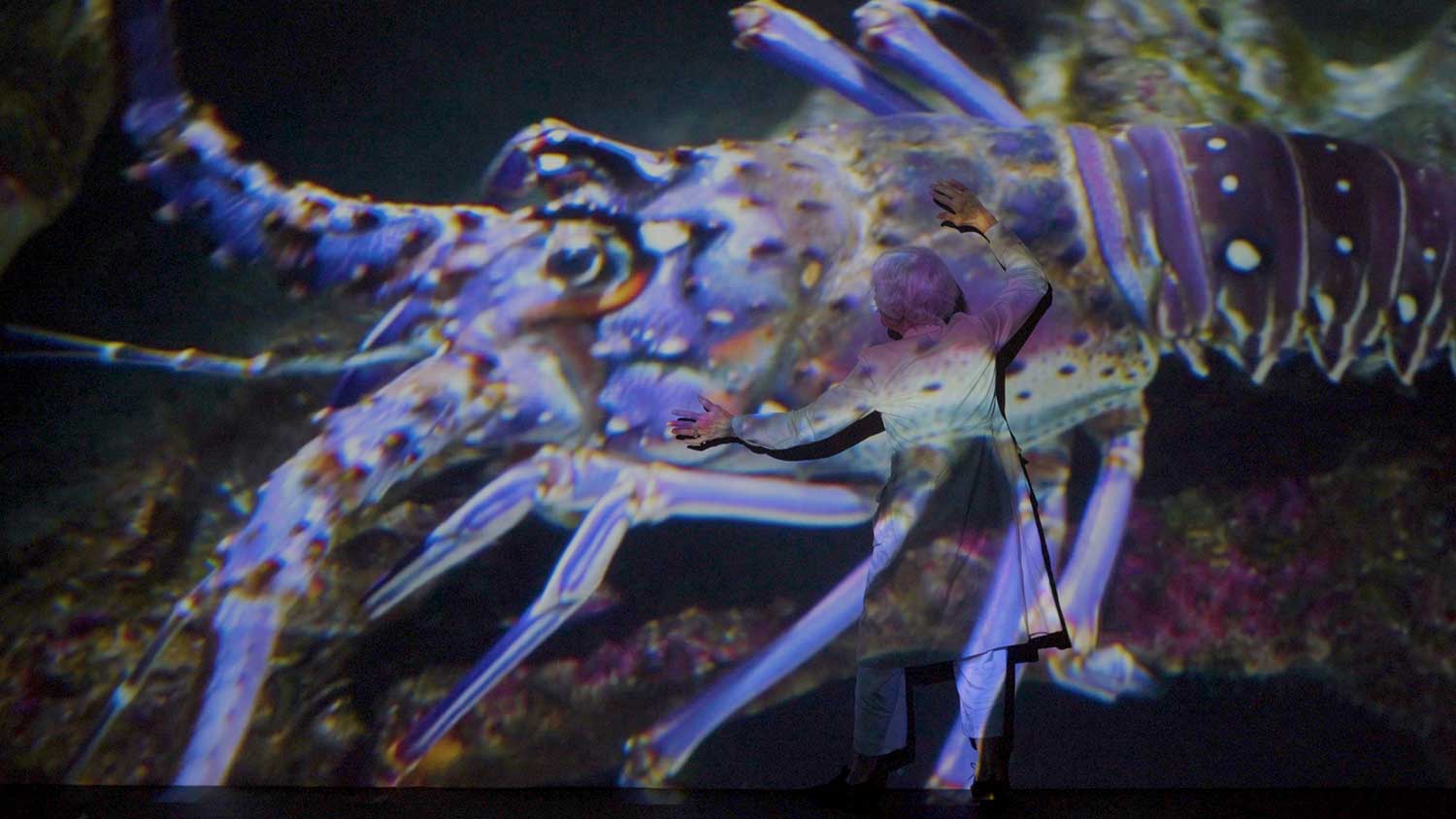

Dion frequently places his work between two bookends. The first is the enthusiasm felt by Europeans when discovering that the world was far more diverse than they had ever imagined. The second is the current sense of mourning for the loss of that diversity as animal and plant species are eliminated by development, pollution, hunting, and climate change. The word “melancholy” has appeared in many of Dion’s recent projects, and he has mentioned being the emotional mouthpiece of his many friends in the sciences. His work Field Station for the Melancholy Marine Biologist, 2018, constructed for Prospect 4 in New Orleans and installed in May 2019 at Storm King Art Center, reads almost like a memorial. The space recalls the tight workspace of a lonely scientist tinkering with subjects and tools that feel simply quaint — if also out-of-sync and futile — to the contemporary moment, especially given the gravity of marine life. The entire installation is hyperreal, so that every single object — and there are thousands, from postcards to pens, microscopes, and jars of specimens — is carefully selected and staged to appear just as it would, like a stage set that would also actually function as a field station. Most memorable when peering through the cracked window panes is the image that forms in the mind of the person who went to the station day after day, to study the books, collect specimens, and write field notes, monitoring the incremental but demonstrable changes unfolding in our oceans. I feel a swelling feeling of devastation at the futility of the endeavor, and also of inspiration that day after day this person dedicated his or her life to this project. Such a demonstration of will fills me with the hopeful reminder that human beings may also be the culprits of positive environmental change.