In “How to Disappear,” a song from her last album, Norman Fucking Rockwell!, Lana Del Rey leads us to expect a how-to manual, but she gives us a poem instead:

“Now it’s been years since I left New York / I got a kid and two cats in the yard / The California sun and the movie stars / I watch the skies getting light as I write / As I think about those years / As I whisper in your ear / I’m always gon’ to be right here / No one’s going anywhere.1

Such an unabashed display of sentimentality is compounded by the photographic and/or painterly image on the album’s cover, in which Del Rey clings to a man, a handsome man, and she clings to the American flag and Americana, and she clings to kitsch and she clings to melodrama and the problematic histories that each of these normative and patriarchal phenomena might provide, even as they all sink together. Staying with the doomed ship (loving the doomed ship, even) is an act of radical generosity.

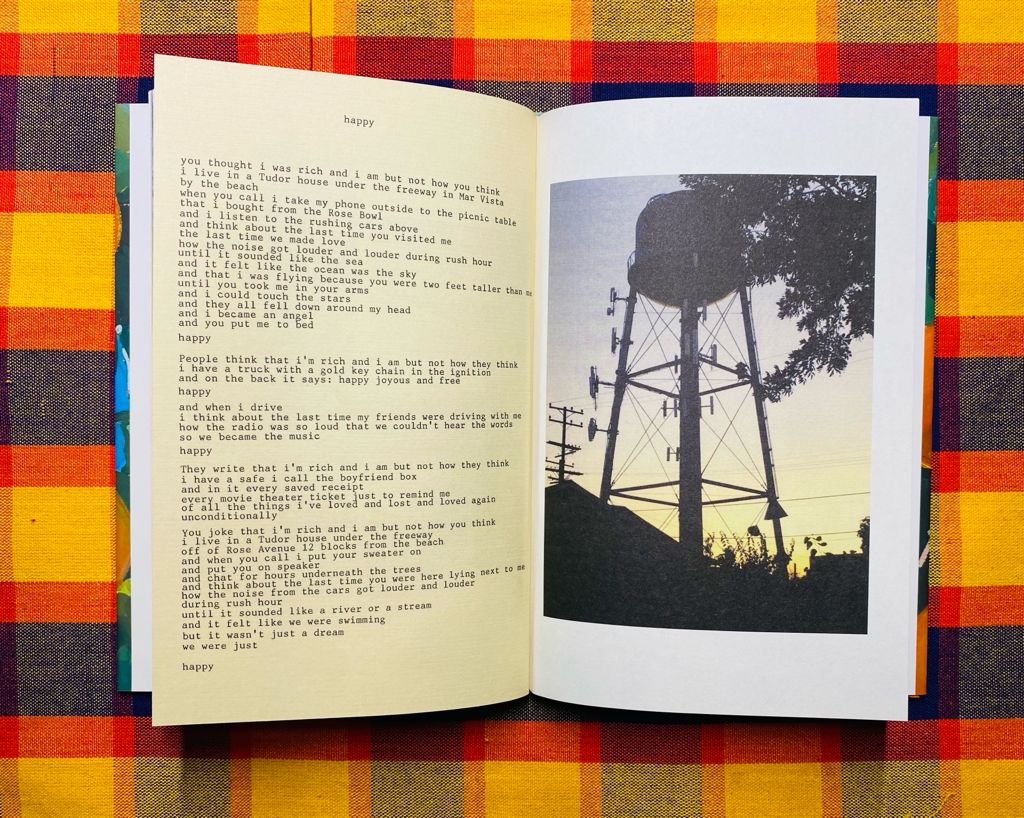

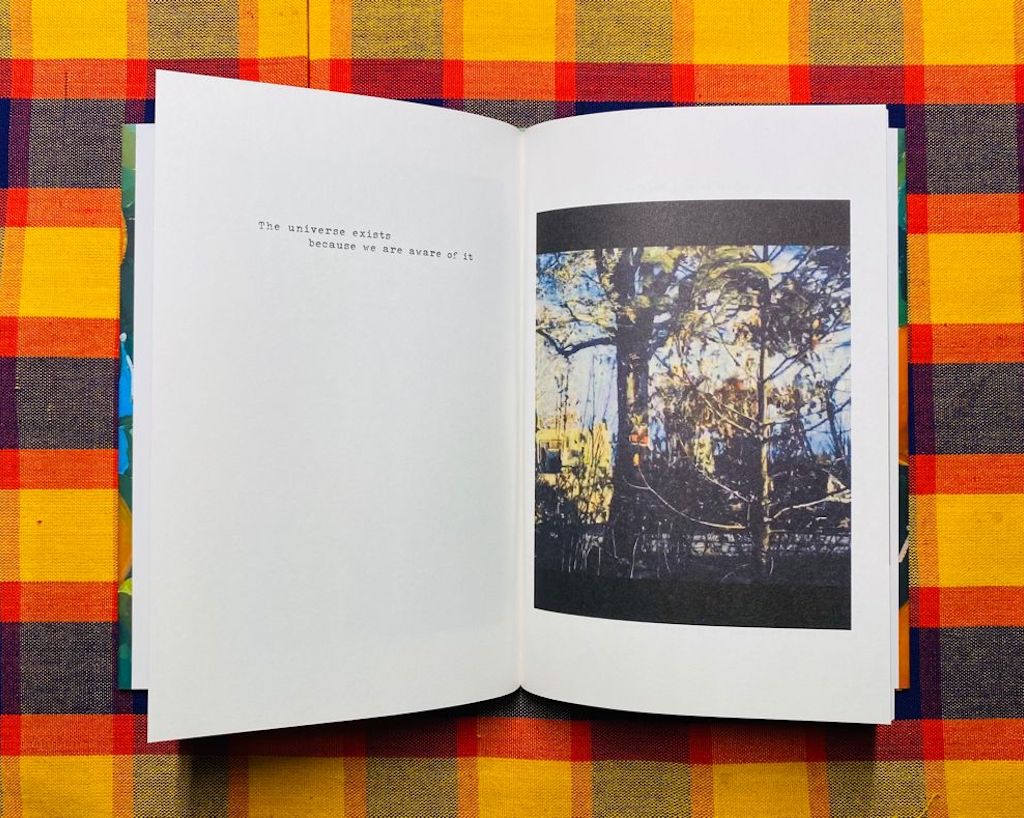

Indeed, one way to disappear would be to live one’s so-called real life as if it were Written on the Wind or Imitation of Lifeor Melancholia or Brokeback Mountain or cherished photographs that we want to be documentaries but are in fact fantasies (as might be the case with the Del Rey’s photographs, both archival and original, that are interspersed in her new poetry book Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass). It might be too painful to experience life as if it were a movie, so we insist, for our own sakes, that Del Rey must be ironic, that she is deconstructing something, that she is telling stories of fictional characters from whom we can maintain a respectable distance, or that these stories are only about her, someone who we can relentlessly critique for claiming to speak only to majoritarian values. We praise her when she appears to disappear, that is, when her work and her histories, her storytelling, her photography, the daydreams of the early 2010s, the men she met along the way, disappear in favor of some hidden meaning we ascribe to her work that we insist is actually anything but sincere if we are to enjoy it (and if it is, in fact, sincere, it is all wrong). Yet we might believe the artist when she writes of Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass, “[These poems] are eclectic and honest and not trying to be anything other than what they are.” If Lana Del Rey is “about” anything, she is “about” belief, which is not the same as sincerity.

It has been suggested that Del Rey finally “grew up” in Norman Fucking Rockwell!, that her melodramatic fantasies about cocaine and daddies and biker gangs finally disappeared, and with that suggestion, I worried that I too would disappear, because I (like Lana, I think) am not ready to grow up, nor do I automatically equate the death of youthful fantasies with artistic quality.

My discomfort ran deeper than the annoying need to tell everyone, and tell them often, that I loved Del Rey’s work since Video Games first made its way, with confused and thrilling clicks, into the discourse in 2011. There was absolutely nothing like it, hearing that song for the first time, in a strange house across the street from a cemetery while on study abroad in Cambridge, UK. I was not a bad girl; I was not an object of desire; I was not as self-destructive as I wanted to be (yet); I still had not disappeared. In Del Rey fashion, I would stand outside the apartment that I shared with a charming stoner and smoke cigarettes and look into the cemetery and I was sure I would see Sylvia Plath’s ghost. I had heard somewhere that Plath and Ted Hughes had first met at that burial ground on Botolph Lane, though I later learned that I was mistaken. One might still love a lie, so every time I return to England I stop by that very street and imagine myself there and imagine Sylvia there among the tombstones. I leave a cigarette butt each time in and among the mossy cobblestones on Botolph Lane — an ersatz and suicidal memorial to myself.

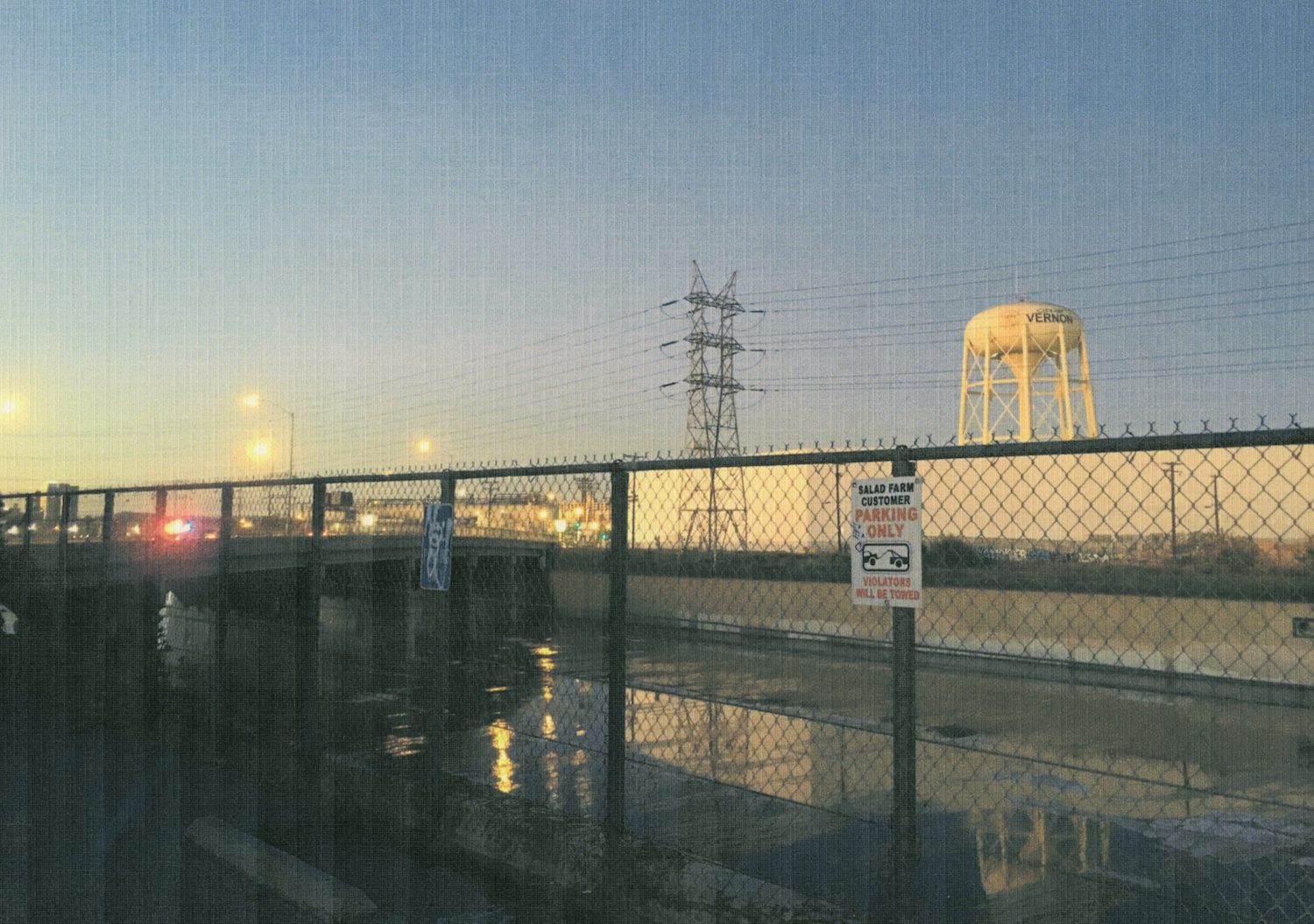

In “The Land of 1000 Fires,” one of the poems in Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass, Del Rey pays homage to a bleak, industrial wasteland just outside of LA proper. It bears no resemblance to Botolph Lane, and yet they are the same. My framer is in Vernon, and I love to drive around with my boyfriend Felipe. Vernon’s beauty appeals to those who might wish to be swept up in it, to be transient in it, to die in it, and those who do not identify with it and instead marvel at its juxtapositions of water and steel and expansion and claustrophobia and hidden alleys and open spaces that cannot hide violence. I have come to learn, thankfully, from Lana and Felipe alike, that both ways of relating to Vernon are beautiful and valid.

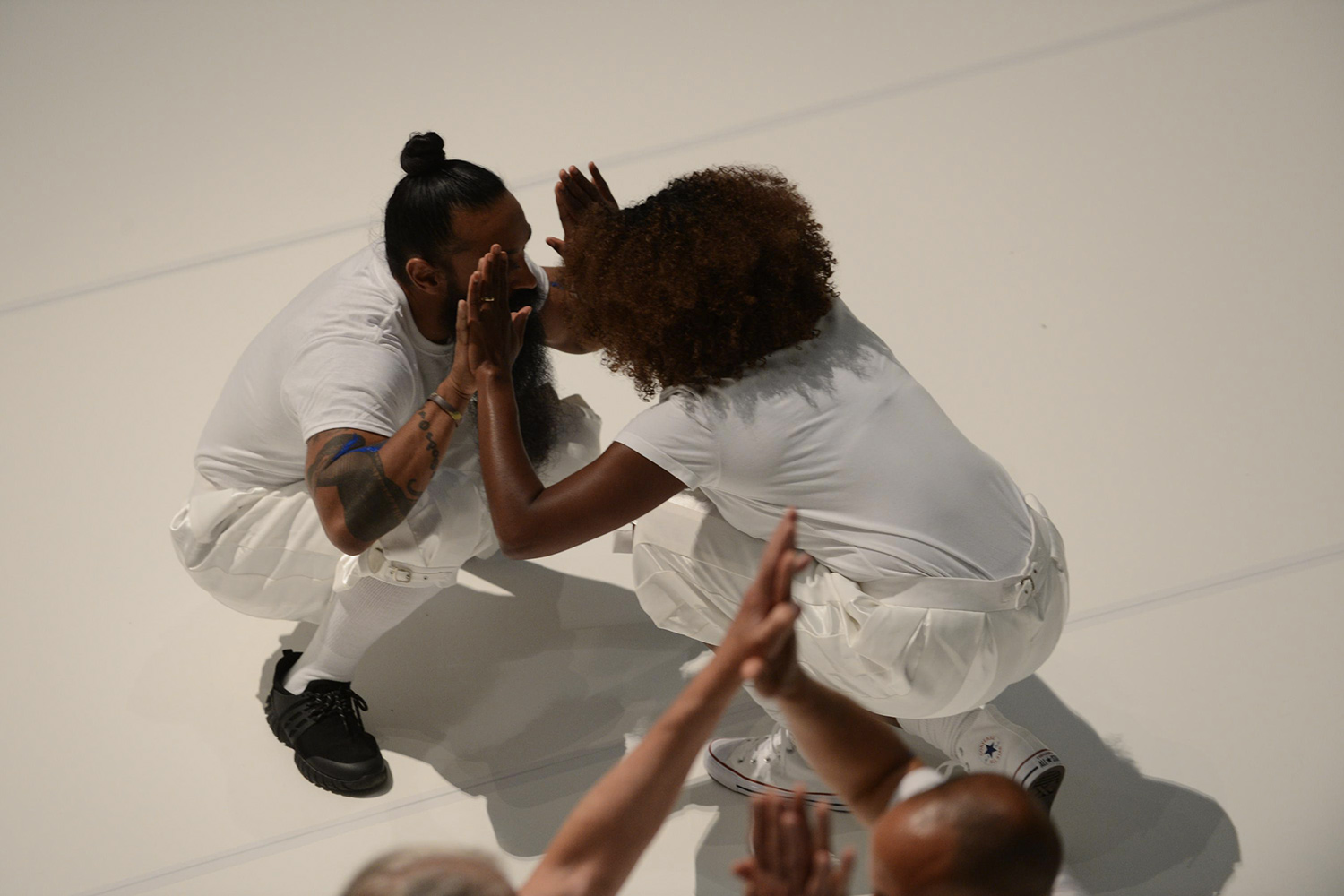

It follows that perhaps the only major change I would note between Born to Die and Norman Fucking Rockwell! is that in the former, I/we/Lana assume that he, the handsome chimera, will leave, no matter the immediacy of the beautiful pleasures and traumas he brings.

But with Norman Fucking Rockwell!, I would quote “Love Song” from the album as characteristic of a new outlook: “I’d like to think that you would stick around.” What we have learned in the interim, perhaps, is that we deserve to find happiness in certainty itself and not only the certainty of loss.

Of Vernon Del Rey writes, “I’ve never really fallen in love / but whatever this feeling is / I wish everyone could experience it.” Only those who have truly loved claim to have never done so, and there is nowhere better to feel, really feel, that paradox than in Vernon or on Botolph Lane, where trucks come and go, filled with drifters and Sylvia Plath and dead bodies maybe, or, just as thrillingly, nothing of cinematic or literary or photographic note at all. Falling in love, refusing to disappear, writing a love song with a happy ending: these are our mandates now.