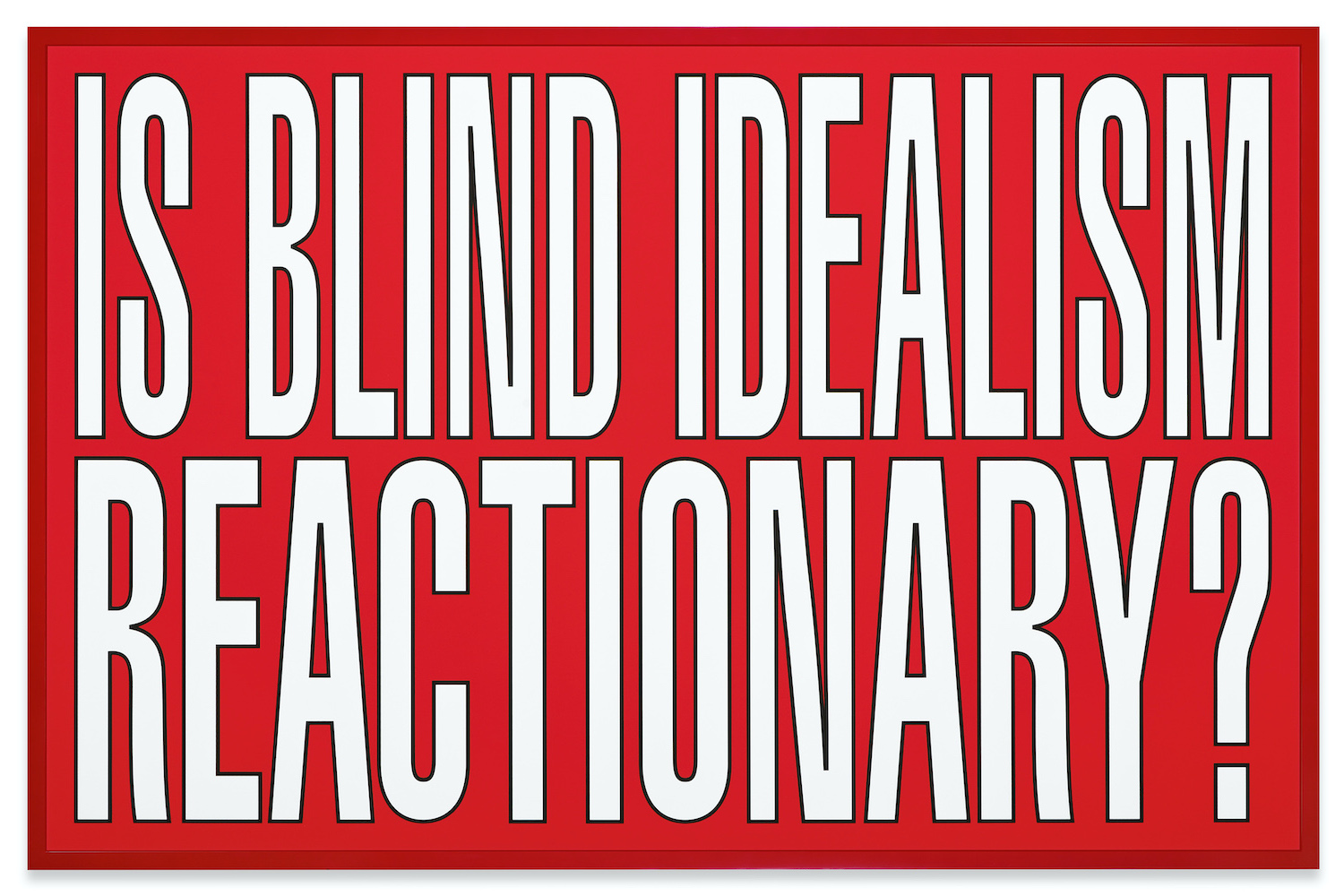

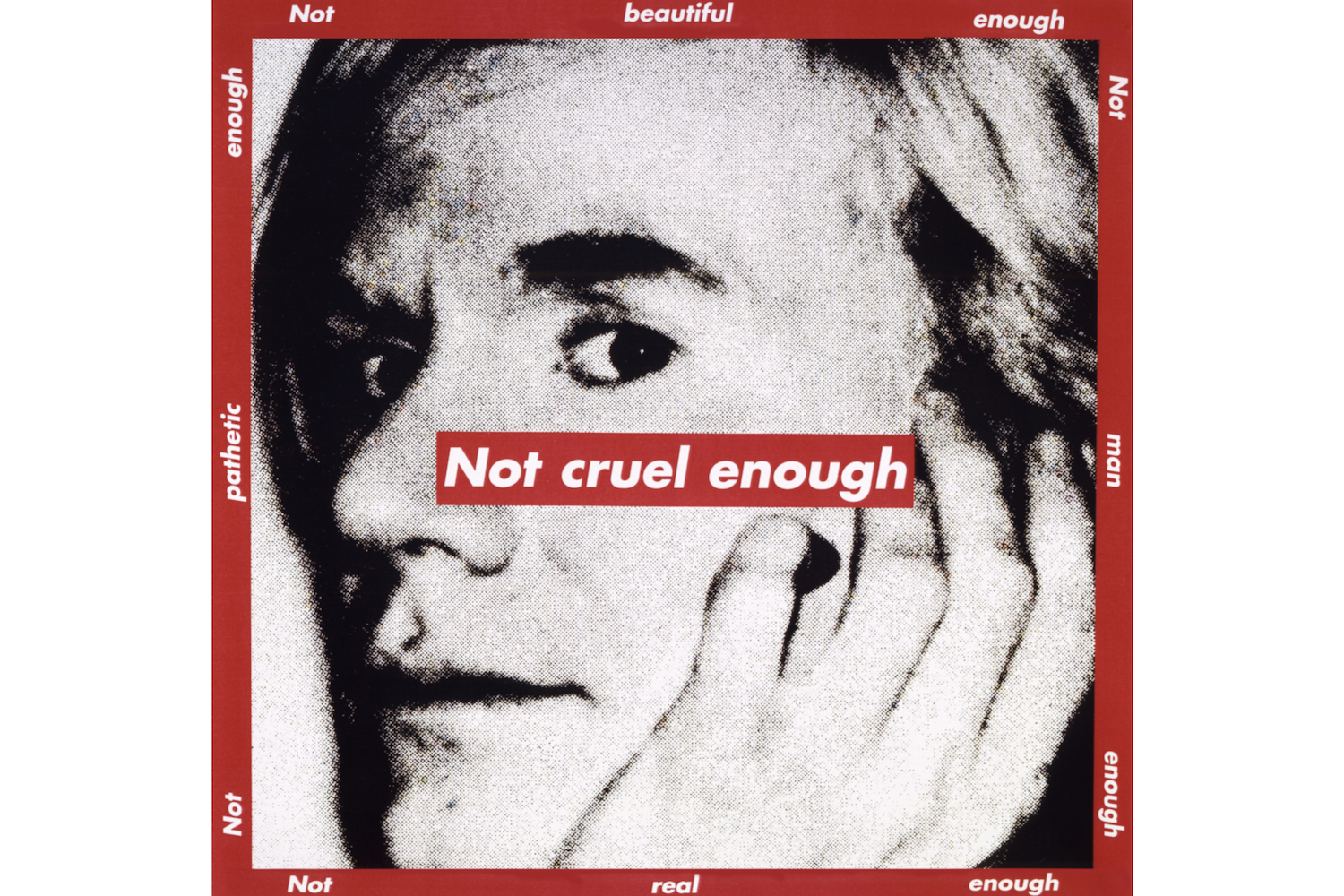

Barbara Kruger’s work has come to represent a host of negative affects for art historians and critics, and it is in those dark, painful, and discomfiting emotions that the work finds its criticality and deconstructive qualities. So we are told, or perhaps, ironically, indoctrinated — fictions become history, indeed. We understand Kruger’s work to be oppositional, paranoid, skeptical, probing, threatening, refusing, dismantling, denuding, castigating, withholding, chastising, ridiculing, combative, dissecting, extracting, exposing, embarrassing, accosting, and detached. In many activist contexts, these qualities are necessary, but I wonder if they take a toll, if they produce stasis instead of opportunities. I have always thought of Kruger’s use of text as written on the wind, as it were, somewhere between the page and the pen and an untethered gust. Her words and her writings are emissaries of the tradition of melodrama in which the film need not be believed or disbelieved, loved or reviled. The melodrama’s medium is itself belief; it is love and revulsion. Perversely, the application of terms like cool, critical, and detached to Kruger’s work allows the historian or critic to enact their own detachment from empathetic and capacious looking, from the handmade, from the emotionally excessive, from all that might be considered sincere, from a poetics as such that does not require the validation that visuality and criticality provide.

The negative emotions that characterize Kruger’s work might evince more general fears about language, imagination, and how we choose to mobilize them. The “paraliterary” turn, to quote Rosalind Krauss, that accompanied post-structural theory carried with it a concern that literary criticism would become fluffy, insubstantial, anti-critical, and even complicit—melodramatic, even. 1 Krauss discusses how the literary qualities of post-structural theory were used to denigrate it, and this war around criticality is distinctly gendered. She describes Derrida’s famous lecture on Van Gogh’s shoes, in which Derrida speaks in a falsetto, as if he were “a woman who repeatedly breaks into the measured order of the exposition with questions that are slightly hysterical, very exasperated, and above all short.”2 It is hard to not be reminded of the standard discourse around Kruger’s photo-collages here. Derrida’s feminized performance, according to Krauss, “functions to open and theatricalize the space of Derrida’s writing, alerting us to the dramatic interplay of levels and styles and speakers that had formerly been the prerogative of literature but not of critical or philosophical discourse.” 3 The feminized voice (or, considering Krauss’s evocation of theatricality, we might call it a queer voice) therefore enacts the literary or poetic quality of Derrida’s deconstructive strategy. Yet again, the Other becomes the un-consenting bearer of intellectual novelty without receiving serious attention in and of itself, which is a frequent phenomenon in Krauss’s writings. Indeed, Kruger’s work often becomes de-politicized and de-poeticized inasmuch as the artist’s feminist activism becomes subsumed into post-structural generalities that purport to speak to the subject, even as they obliterate the gendered, sexed, raced, and classed body in service of a universalizing deconstruction. In any case, why do we always focus on the shortness, the exasperation, the abruptness, of Kruger’s words and not allow them to aspire to narrative, to paragraphs and memoirs?

Of central importance is Krauss’s assertion that the new paraliterary texts, like those by Derrida and Roland Barthes, cannot be reduced to critique: “The paraliterary cannot be a model for the systematic unpacking of the meanings of a work of art that is criticism’s task.”4 Krauss goes on: “Nothing is buried that must be ‘extracted’; it is all part of the surface of the text.”5 Her argument does not, however, engender an art-historical appreciation of poetry. Indeed, the literary faded away into a clichéd rehearsal of the text’s construction as such, always in service of the dominance of visuality and the surveillance of critique (not to mention the primacy of the institution in legitimizing those frameworks). While post-structuralism insisted there was nothing behind the text, it also negated the possibility of anything within the text, other than pessimistic signs of its own making. I do not think, however, that this is what the poetic writings of Barthes, Derrida, or Julia Kristeva aim to achieve. Like Kruger, their work is as much affirmative as deconstructive, and equally connected to a multiplicity of meanings as one in particular that pricks and draws blood. However, despite a reliance on Barthes, Derrida, Kristeva, and Kruger (who has become the exemplary artist for how we teach postmodernism) to tell its stories, art history remains entrenched in critical/complicit binaries that relentlessly detach poetics and academics. I do not tell any of my professors that I teach my undergrads to read Barthes’s Camera Lucida as if it were poetry, for example. Sometimes being sad and gay and craving sex in the face of death is enough. In fact, I have always thought that I could only write about Barbara Kruger through poetry and not academic prose.

Unfortunately, the fad for auto-theory has not helped the situation, seeing as much writing in that genre devolves into a box-ticking process of hitting all the coolest texts while universalizing relentlessly from a place of self-narration, drenched in the irony that privilege affords. Yet, to add to a paranoid litany, as is customary in academia, it must be noted that those who focus on sincerity likewise miss the point, fascinated as they are by a masculinist, heteropatriarchal, and paradoxically elitist anything-goes attitude. I am thinking here of David Foster Wallace’s “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction,” which is perhaps the ur-text for the problematic and revered Quentin Tarantino or Lars von Trier brand of sincerity, which is often merely a masquerade for sexist and racist nostalgia.6

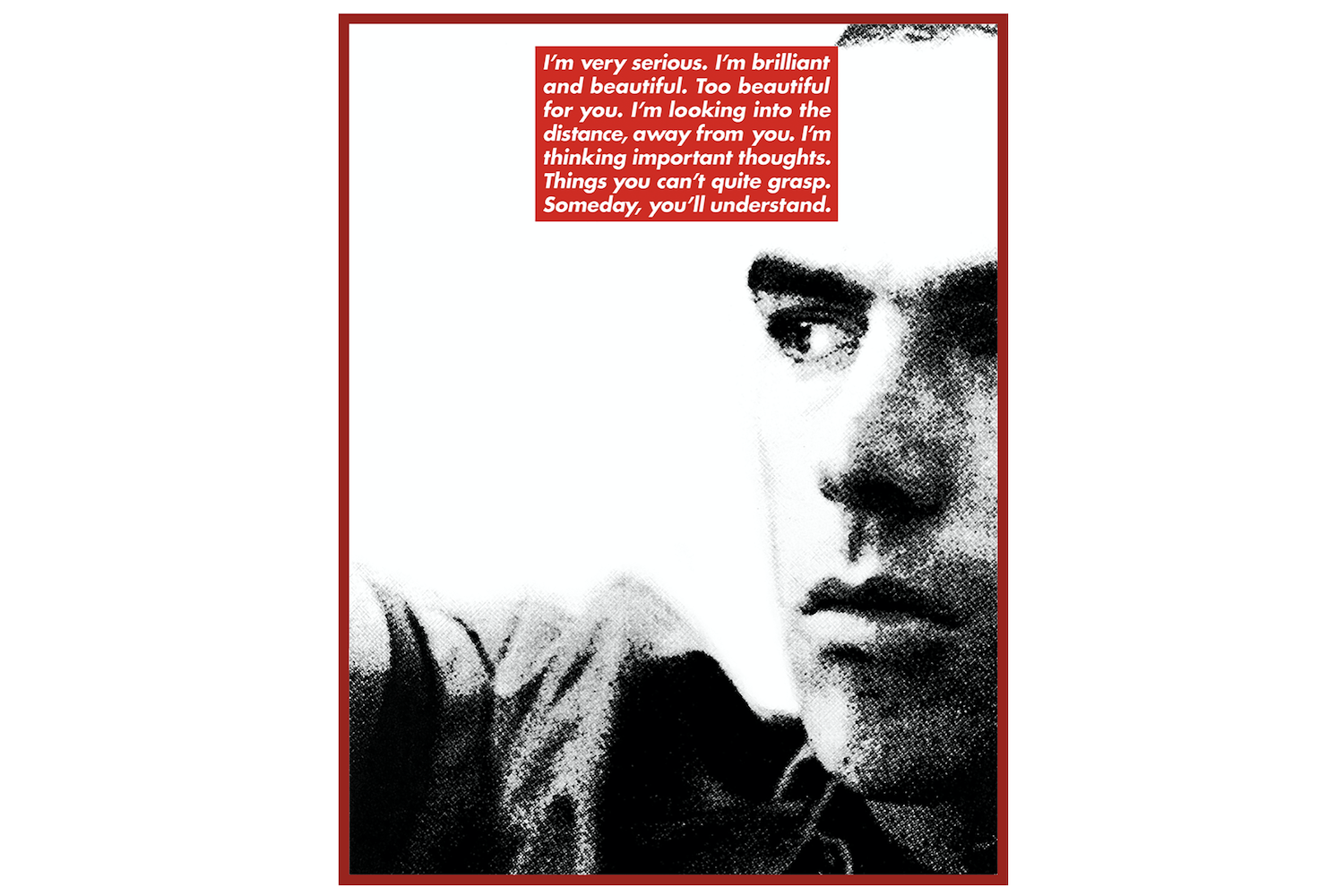

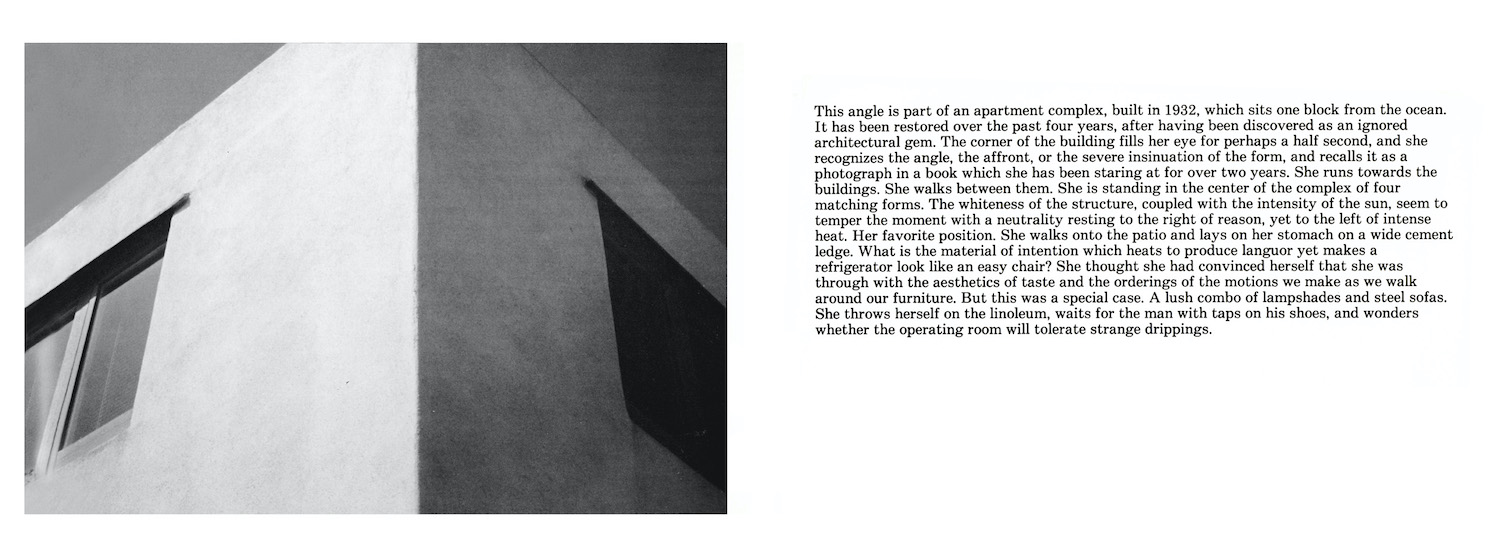

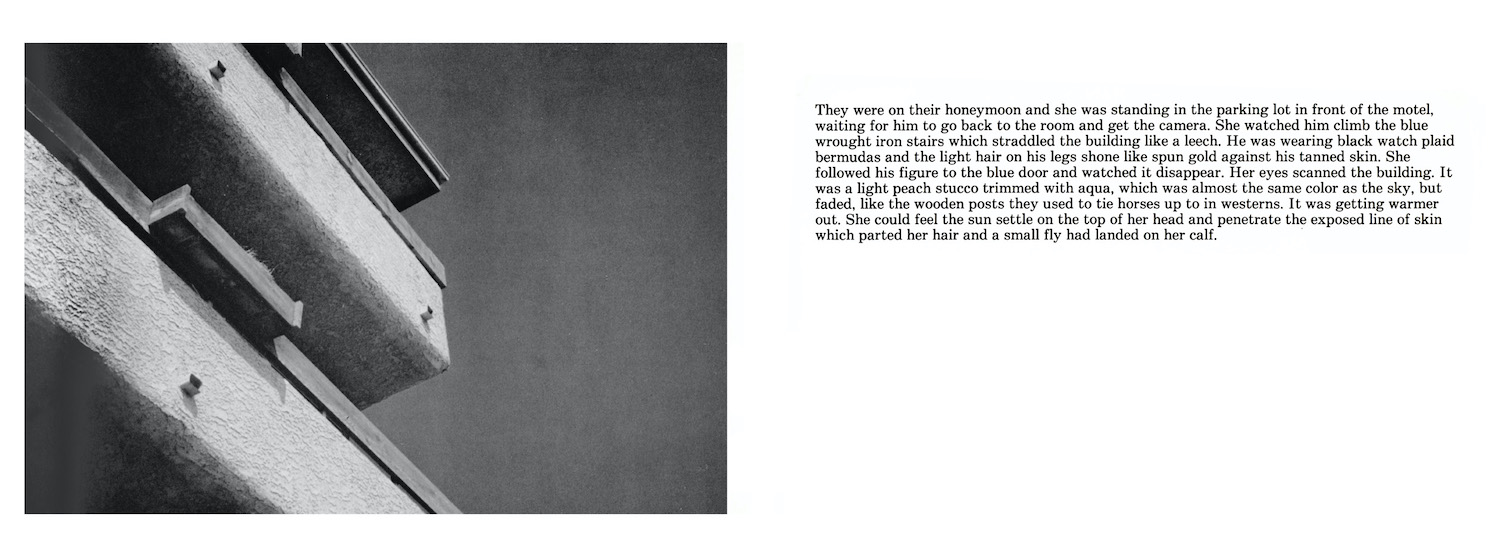

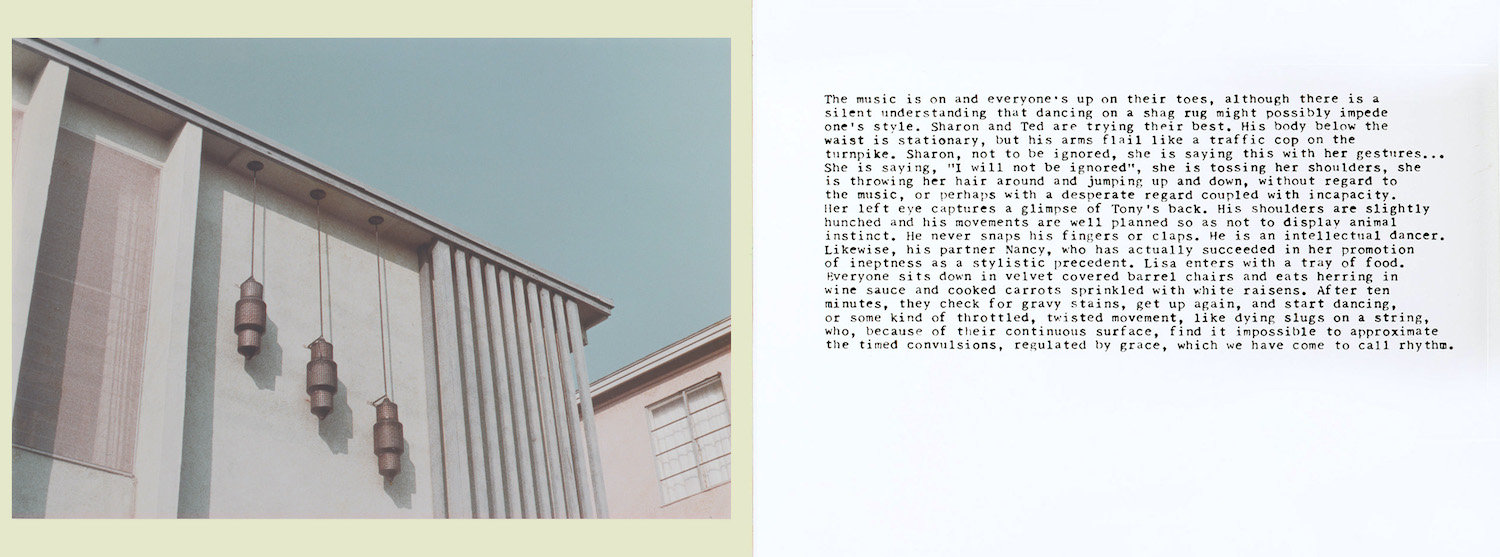

For these reasons, we might consider Kruger’s “Picture/Readings,” a series that necessitates a sustained engagement with its sentences and stories that precedes and even precludes our desire to fold them into critique. Completed in 1978 and self-published, “Picture/Readings” combines images, largely of the exteriors of houses in Berkeley, Los Angeles, and Deerfield Beach, Florida, with texts of filmic, novelistic, and melodramatic ambitions. Rather than short bursts of words scattered among images, the stories in Picture/Readings are long by comparison to Kruger’s more famous work and unceremoniously formatted in blocks. If one wanted to write a dissertation on “Picture/Readings,” one could certainly argue for the importance of architecture in Kruger’s photo-collages, since they are themselves syntactic architectures made from blocks of text and image building upon each other.7 What is there to be said, however, about Kruger’s words here? They are not declarations, but rather stories or narrative scaffoldings that interweave and become the built environments of a life, a psyche, a series of loves and disappointments, of bodies that come together and disentangle. For us to allow Barbara Kruger to tell a story would change everything.

One scenario in Picture/Readings recalls Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1964) and the latently queer film noir from which it emerged. Kruger’s protagonist Gail is listless and beautiful. With nothing to do but smoke and watch TV, she looks outside and considers the nature of the column that adorns the apartment complex. That glamorous, erotic boredom becomes akin to a film: “It was just like Gone With the Wind, having that column outside your window.” Of course, no life is actually just like a movie, even if the movie is Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. Kruger goes on:

She is looking straight ahead at Johnny, who is wearing a gray shirt. His head is buried beneath the hood of a red Mustang. His forearms are tan and full and the veins stick out of them. She loves that about him. She walks up behind him, throws her arms around his waist, and pushes her face hard into his back. She catches him off balance and pulls him to the ground, under the Mustang, and forces him, along with her, to stare at the underside of the car, promising him, that if they stare long enough, it’ll turn into a beautiful set of doric columns.

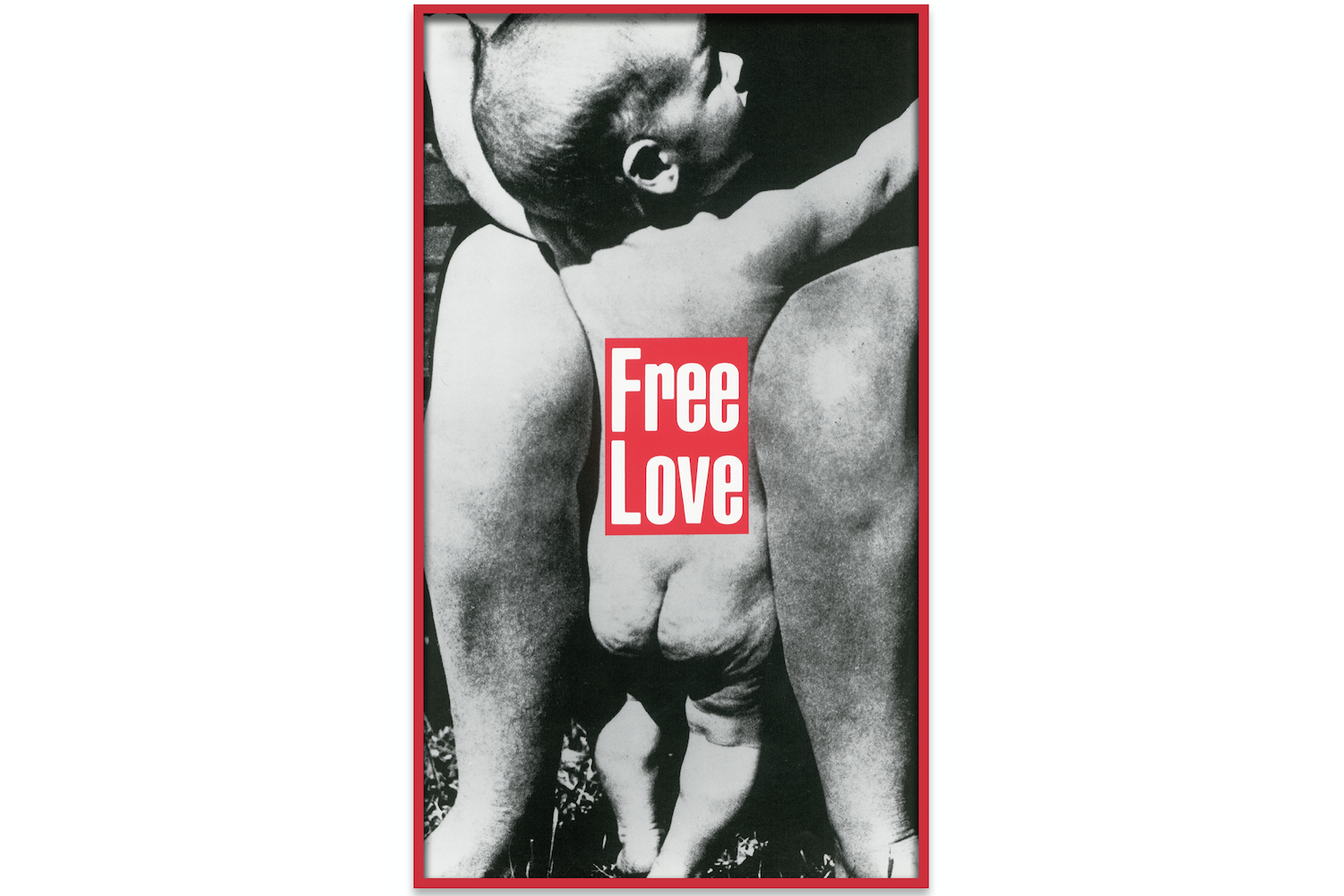

We might remember Derrida’s feminized, frantic interruption that Krauss relays and suggest that Gail enacts a similar self-insertion into the masculine narrative of her boyfriend who archetypally works at a gas station, in all its David Lynch glory. Laura Mulvey, a longtime theorist of Kruger’s work, and Peter Wollen write in their breathtaking essay on Tina Modotti and Frida Kahlo that beauty was an affliction for Modotti, a disability even, that precluded her from attaining critical success on her own, apart from the great men who history tells us enabled her.8 Likewise, Catherine Breillat writes: “For it is not love we crave but the look, and the one who inflicts, looks a little.”9 So too might Gail be afflicted, and upon her we and Johnny look; we inflict. We look and we inflict, just as we do when we undertake a formal analysis of a work of art. When reading Gail’s story though, we might jump immediately from form to content without dissecting and disembodying her. We might long for a happy ending, for love, at last, to save us from banality and tie us to countless others who have sought difference-within-cliché or oppositionality within complicity. We long for feminist optimism interlaced with lust and despair.

With these possibilities in mind, with the possibility for minoritarian subjects (artists and fictional characters alike) to maintain problematic connections to mass-cultural phenomena, we might release women, queer people, and people of color from perennially bearing the burden of theorizing difference and avant-gardeism. In any case, to call “Picture/Readings” either critical or complicit would miss the point entirely and neglect the constellations of identification between those poles. Sometimes, a stereotype is an action and not merely a gesture, to cite Craig Owens’s foundational essay on Kruger.10 A stereotype might be just appealing enough to get us underneath that car and consider the truths of engines and Doric columns and love. We need not always look under the hood, as it were, since it is all right there before us: it is the muscle car with a handsome, inattentive man beside it, ready to drive us off into the sunset. The cliché, the stereotype, and the melodrama all move, for we are always rearranging ourselves in proximity to them, and within that rearrangement might lie the pleasure of veins protruding from skin or the pleasure of rejecting such saccharine reductions of experience.