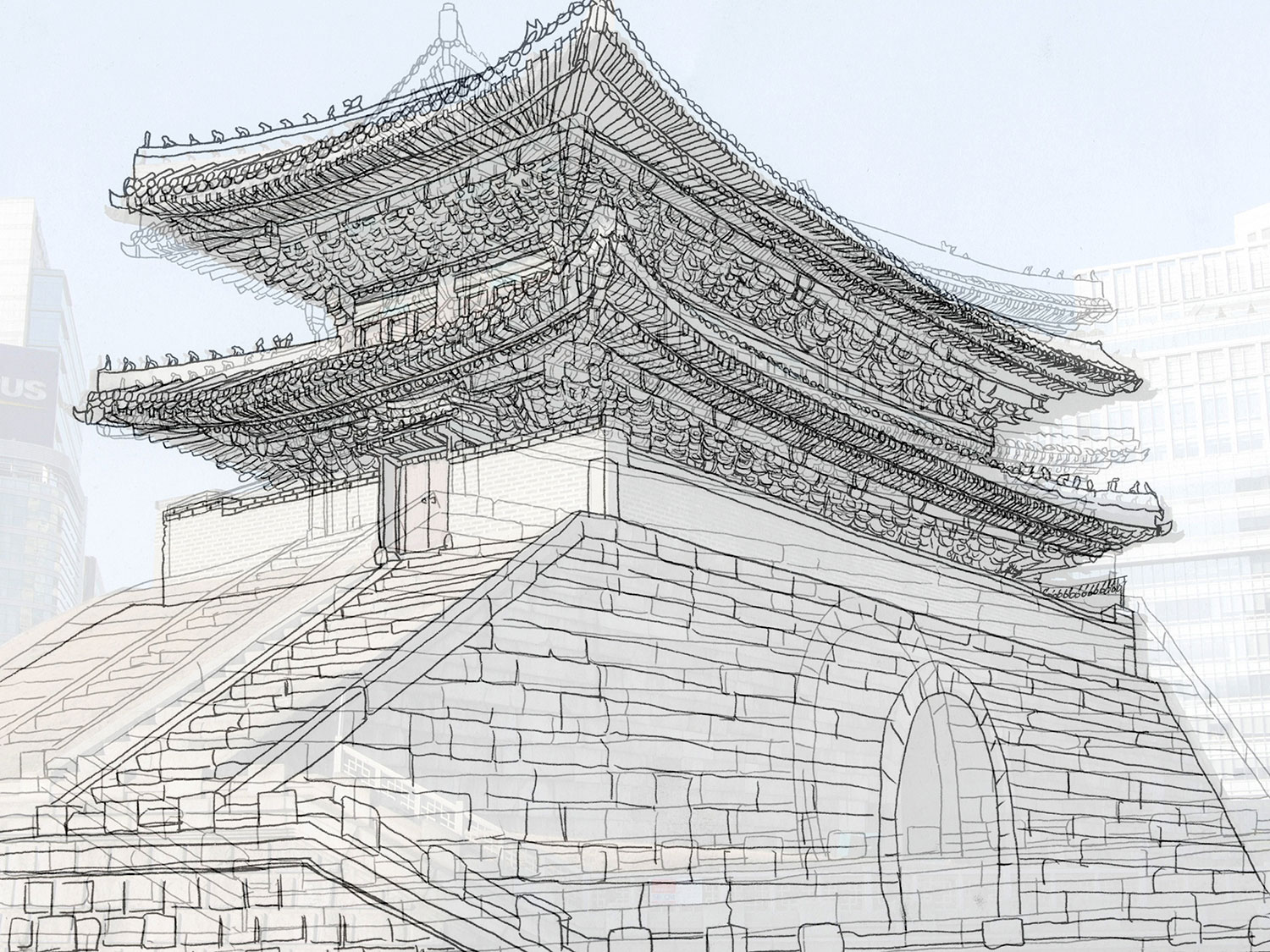

I hadn’t been back to China since 2005. An eternity considering the country’s rapid transformation, its urbanization and economic development, which started some twenty years ago in an attempt to catch up with the era of modernity. That was when I began traveling there myself, up to several times a year, each time feeling like a privileged witness to dramatic changes: new sidewalks, highways, towers and shopping malls. And simultaneously, in metropolises like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, the first exhibitions and cultural infrastructures that enabled Chinese contemporary art to transition from the underground to the public eye.

In recent years, the increasing pace of this transformation has been constantly reported in the news. China’s prosperous economy, combined with major cultural reforms, have encouraged investment in the art market while generating a sudden proliferation of hundreds of museums and dedicated institutions, both state run and privately funded. Record-breaking market and auction results have placed Chinese contemporary art at the forefront of international attention.

In the meantime, however, other kinds of shocking excess were also reported. The power of the Communist Party remains largely unchanged, and there have been numerous examples of social control, limited freedom of expression and censorship, especially on the Internet. Economic development has given rise to unprecedented political corruption and moral degradation, generating extreme social disparity as well as serious environmental crises.

Today, China finds itself at a crossroads. What is happening to Chinese contemporary art, even when positive, cannot be separated from a rapidly changing context, both extravagant and ambivalent, challenging and ideologically confusing.

I wanted to go back and see for myself. Because China’s social changes are to some extent expressed through rapid physical transformations, I chose to record my whole cross-country journey with a camera. Snapshot photography has the advantage of being an immediate and objective mirror of reality while simultaneously offering the viewer a space for personal interpretation. It’s an ideal support when a situation can’t be easily put into words, and when any attempt to analyze it (particularly by an outsider) might turn out to be hasty or biased.

I’ve returned to China twice over the last few months, focusing mainly on the art world and its social background. I visited the main artistic centers, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Hong Kong, as well as some remote rural areas where audacious artistic projects are taking shape. It was impossible not to be fascinated by the new face of the country, the telescoping of the most advanced and ancient timeframes, a rate of development that is no longer imaginable in the West. I was totally amazed by the metamorphosis of the artistic landscape, its internationalization, its energy and vitality prompted by considerable investments of finance and media. Against a background of two large-scale global events, the 9th Shanghai Biennial and the 4th Guangzhou Triennial, I attended many openings and conferences, and I visited a myriad of new galleries, art spaces and museums, some of which were still under construction. I was stunned by the gigantism of some of the newly opened state museums, such as China Art Palace and Power Station of Art in Shanghai, as well as the growth of the 798 art district in Beijing which, early in 2005, was still in an early stage with just a handful of galleries. Today this art zone includes more than 150 galleries and art institutions, including Arte Continua, Boers-Li Gallery and the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, as well as plenty of trendy shops and restaurants that attract hoards of tourists and local hipsters. It’s a paradigm of the new culture that has emerged over there in just seven years.

All this might give the impression that China is a place where anything is possible, where the future of the art world will inevitably play out.

However, under this spectacular surface, the reality of the art world there reflects the profound paradoxes of the society upon which it thrives. Commercialization and censorship have largely shaped the art scene, promoting a mainstream interest in commercial success. Yet the frenetic expansion of museums (which actually has more to do with national pride and profit) is not without risk. The speed of development, as well as a lack of consistent funding and professional expertise, have resulted in a very fragmented scene without much cultural coherence. It is striking that a majority of exhibitions are focused on Chinese contemporary art, yet there is not a single museum or permanent collection that displays a comprehensive overview of the last thirty years of its history. There are countless cacophonous promotions that treat Chinese contemporary art as a fashionable brand. The most commercially oriented shows are mounted alongside seriously curated exhibitions, like the valuable artist retrospectives on Zheng Guogu at Vitamin Creative Space in Guangzhou, Yang Fudong at OCT Contemporary Art Terminal in Shanghai, Liu Xiaodong at Today Art Museum in Beijing, as well as thematic shows featuring the young generation of post-Mao artists: “CAFAM Future: Subphenomena” curated by Beijing Art’s Museum of Central Academy of Fine Arts, which traveled to Guangzhou (the Center for Art and Culture was inaugurated on this occasion), and “ON/OFF” at UCCA in Beijing.

Other emerging structures like the Minsheng Art Museum and Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai, or the Times Museum in Guangzhou, while financed by banks and real estate companies, demonstrate their commitment through clear positions as contemporary art institutions focused on local dialogue , education and cultural exchange. There is potential for such new museums to build their collections and fill their oversized spaces by cooperating with international museums. Shanghai’s Power Station of Art hosted an exhibition organized by Centre Pompidou in Paris with some 119 masterpieces from its permanent collection. This option may become increasingly attractive as many public-funded European museums begin to face budget shortages and a lack of suitable storage space.

As a part of the museum boom, I also would like to point out the remarkable initiatives taken by individual artists who have attempted to develop critical programs in museums. They either create new institutions or take positions of leadership. Their actions are largely supported by their international experiences and charisma (until recently Zhou Tiehai was director of the Misheng Art Museum in Shanghai; Xu Bin became deputy director of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing and Zhang Peili is director of OCT in Shanghai). Organizations such as Video Bureau (led by Zhu Jia and Chen Tong), Arrow Factory (Pauline Yao, Wang Wei and others) in Beijing, Borges Libreria (Chen Tong) and HB Station (Times Museum, with Huang Xiaopeng and Xu Tan) in Guangzhou are all admirable examples of new artist-run spaces that promote research, education and dialogue with the public.

Although most of the new museums and organizations are products of intense urbanization, the art community has started to develop a collective consciousness of ecology and spirituality. They are now increasingly interested in exploring long-overlooked rural areas as their bases for experimentation. Vitamin Creative Space, a decade-old independent space and gallery (Guangzhou and Beijing), is now building its new headquarters in a rural village where artists and intellectuals will be encouraged to work through a new model based on sustainability. I was also very pleased to witness the most recent developments of the “Age of Empire” by the artist Zheng Guogo in the countryside of Yangjiang (county of Guangdong province), an ongoing laboratory of art production and social negotiation that is one of the brightest and most meaningful projects in the Chinese context today. This integration of cultural production and rural life can also be seen in the Bishan Commune project led by activist and curator Ou Ning.

Of course, the reality of Chinese society is far from utopian. My trips coincided with some major events that revealed contemporary China’s darker side. For me, someone used to having full access to the Internet, it was not easy to be suddenly cut off from the world due to government control. But I was there during an intense political season. Within an interval of a few days, the two biggest global powers, namely the United States (presidential elections) and China (the 18th Congress of the Communist Party), determined their new leadership. In China the event generated an enforcement of security bordering on paranoia, with a lockdown of access to even the largest newspapers like The New York Times and Le Monde.

I also experienced historically unprecedented air pollution levels as reported by the World Health Organization. China’s pharaonic transformation has all but eliminated any possibility for the preservation of the environmental ecosystem.

Traveling to China today is like entering Alice’s wonderland. It is full of excesses and paradoxes, with moments of euphoria, terror and absurdity. Many had long hoped that China would become the antidote to the Americanization of the world. Yet China is not, in its current state of transformation, a model of civilization. It is often a magnifying mirror of American production at its worst.

Today China needs an antidote. The freshly elected party leaders have promised to recover “the beauty of China.” Could this slogan be a possible point of consensus between the powerful and the grass-roots society of intellectuals and artists? What is certain, and what I have understood from these trips, is that China today has the means to be master of its own destiny. Let’s hope it can find, like Alice, the right exit. Otherwise, a whole country, a whole culture and a whole people risk becoming lost on their journey toward the future.