Reality: this nominal territory we all inhabit but which no one can own or control. Simply defined, “reality” is the state of things as they are or appear, not as we might wish them to be. Though one might philosophically assume its ontological independence from human concerns, the appearance of reality rests completely on individual perception. The word posits an all-encompassing condition behind which sprawl manifold elements and perspectives. Thus can reality be understood as inherently unstable. Artists have long been preoccupied with the question of reality and our relationship to it; as contemporary reality grows more and more complex, progressive and protean, so the task of engaging it through art becomes increasingly challenging. It now requires a robustness of purpose and approach that not every artist can sustain.

Liu Wei gives us much to talk about on the subject of reality. He now works among a gated cluster of buildings in the untidy migrant village of Shijiacun, not far from Beijing’s world-famous ex-factory 798 art district. That the artist drives to work every day from his home in the uptown Lido area to this makeshift, sub-legal zone has been remarked on by critics who rightly see this journey as at once a physical and historical one, sampling the stages of urban development as it sweeps out with centrifugal force from the city’s core. Liu Wei himself says his working method is closely informed by this environment. Asked how this development makes him feel, Liu replies that this is simply his reality, one evocative of momentum and progress.

The visibility of Liu Wei’s art has increased significantly in recent years. Two solo exhibitions of his work were mounted in 2009, in Paris and Beijing, and his work had a strong presence at both Art Basel and SHContemporary, and in the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art’s survey of key new generation artists. In 2010 Liu Wei appeared in the Shanghai Biennale, and in Spring 2011 the major solo outing “Trilogy” was held to much acclaim at the Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai. This year brings an eponymous show to White Cube — Liu Wei’s first solo exhibition in London. On display is an untitled work from 2011: a miniature citadel rising from a rocky outcrop, all carved from a stack of paperback books; it is vertiginous and futuristic, yet rough-hewn from printed matter — now a carrier of the past. Also there is Merely a Mistake II (2012), a massive, seven-meter-high example from the series that takes urban debris, discarded as Beijing’s old neighborhoods are destroyed (wooden slats, beams and frames), and uses it to fashion strange bolted geometric sculptures evocative of Frankenstein-esque pavilions, altars and portals. They are painted with bland Chinese institutional greens and cheap domestic browns, plus starker tones of lacquered black and light natural wood. The series “Merely a Mistake” presents a strikingly fluent language easily adaptable to different kinds of form, but maintains an ephemeral edge that hinges on the absence of an ostensible purpose or destination for these pieces. They sit at once monumental and prickly in the blanched rooms of galleries that are, as Pauline Yao noted recently in a very thoughtful text, a world away from the cluttered, assaulted architectural context of their origin.

Liu Wei — like his contemporaries Wang Jianwei and Song Dong — makes artistic use of these discarded fragments of architecture and furniture. Pastel-painted wood has become a veritable China-brand artistic medium, and its renewed existence through the components of Liu Wei’s sculptures is easily synonymous with China’s rapid urban development — itself a stock-phrase both within and outside the country. It is under this easily digestible aegis that “Merely a Mistake” is delivered to audiences in London. But while other artists might use this material in the context of nostalgia or history, Liu Wei’s approach is pragmatic. From the perspective of his reality in Beijing, these materials are simply there: the readily available flotsam of urbanization. They could be understood in terms of tangible reality, occupying space immediately before the viewer in relation to their own physical being. For Liu Wei, this emphasis on their plain existence is important because he aims only to extract from what is already there and reconstitute it in such a way as to represent his own attitude. His is less an attitude of artistic expression than simple articulation. “You can’t really create anything. Everything already exists,” he told Jérôme Sans in an interview, “…it’s just a question of how you see it…” There is a powerful determination, too, in how the “Merely A Mistake” series is put together. In the mathematically measured, aligned and conjoined limbs and planes of once-disparate wooden pieces is a potent prerogative of control — something the artist says he has to have. There is structural integrity in the visible nuts and bolts, and it is this synthesis of visual form and the rationale of its production that Liu finds conversant with direct experience as a process of cognition.

Asked what he feels he is most loyal to in his work, he answers: “My attitude.” Lui’s working method follows an organic process wherein the sources of inspiration — conversations and the sights gleaned from day-to-day life, for example — could lie anywhere. This places his work increasingly within the overall frame of a vehement, ever-unfolding reality, one visible and conceivable only at ground level in Beijing. Such a state of quick self-consumption and constant re-forming of the urban body is unimaginable in Europe, where no megacities even exist.

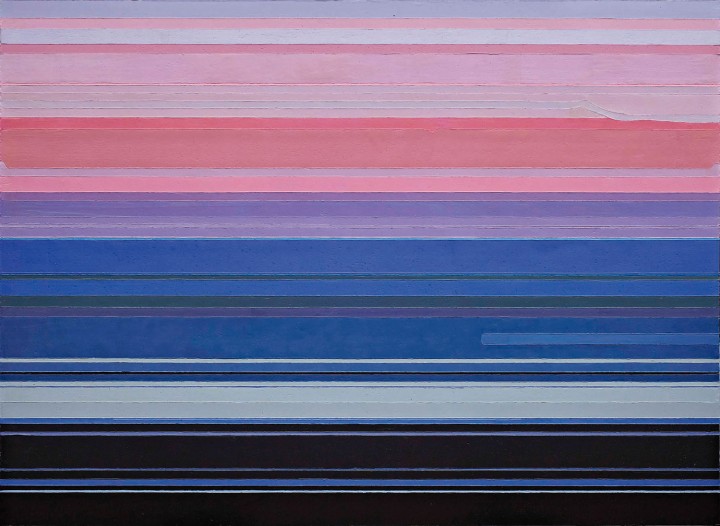

Liu feels the proliferation of short-term attitudes in China has a great impact on the production and reception of art; in the West, he remarks, people take time to solve problems, while in China they may seem superficially to have been solved, but in fact have not. In terms of how this affects his work, this environment provides a richer scope for thinking and making. It contributes to increased anxiety and more progression — a climate he finds productive. “It maximizes everything,” he says. Interestingly, he moves from this idea to that of China’s current structure as being a very simple one in terms of its systems, which serve a singular, full-throttle mentality. What has been deemed the “cyberpunk levity” of Liu’s most recognizable painting series “Purple Air” (2006-2010) suggests a mode of expression for the urban Chinese situation; the paintings’ densely synthetic, humming verticals were struck first with a computer mouse then rendered in atonal acrylic on large canvases by the artist’s assistants. “Meditation” (2010-2011) is a more recent series of sculptural paintings that steamrolls its predecessor’s poppy vertical lines into deeply furrowed slabs of gray oil paint. Gray, to Liu Wei’s mind, represents China: a monotone color that nonetheless requires a mixture of all the others to achieve it.

Instability and irresolution are thus productive states; Liu Wei sees his work as a means of understanding reality, not as an end-point. Surprisingly, perhaps, he finds the latter idea attractive, but inappropriate to the current phase of his practice. He comments also on the contemporary mentality of Chinese artists afraid of positing their work as such. With a note of disappointment, Liu has said that once works are determined for presentation they are already “the dregs of thought.” This sustenance of active authenticity forms one of the many branches towards truth in Liu’s practice. Another found its form in a group of works exhibited at Beijing Commune in 2006 (the so-called “cropped” series), wherein Polaroid photographs of ordinary objects were presented alongside the objects themselves, which had been brutally sawn off to conform to the photograph’s composition. This marks a robust, witty rationale offering an almost embarrassingly literal truth to the viewer.

But beyond these kinds of visceral authenticity, the artist has developed a more socially responsible impulse dealing with reality’s attendant terms — certainty, veracity — in relation to the sociopolitical systems that attempt to influence people’s daily lives. Inlaid in Liu Wei’s outlook is a sensitivity to and suspicion of the outward projection of power, which has materialized in his work most memorably in the form of miniature architectures made of seditious materials. The infamous 2006-7 project “Love It, Bite It” commenced with a collection of international governmental buildings fashioned crudely from yellowish oxhide — the kind used to make dog chews. The idea was born of a connection Liu made between canines’ compulsion towards these treats and the human lust for power, and it was originally intended that dogs be let loose on these knee-high castles. Liu personally feels his is an unstable relationship with society, which he attributes to his idea of how the world is constructed; his practice seeks loopholes — things to be improved — and inserts his opinion as a way to make it better. He recognizes his work as political and sees himself, as an artist, as always responsible for questioning the existing reality.

For Liu Wei, then, the preoccupation remains ever the same: how to portray himself and his practice in reality. A painting might be ‘real’ on the basis of beauty, but what really stimulates the artist is the question of how to turn his work into an influence or attraction within reality’s pervasive field. Now is not the time for finite artistic statements. Liu Wei does not hesitate for a second in defining what, amid his reality in China, are the most pertinent questions society’s members should be asking: “How do you live as a decent human being? How do you enact being an individual?” In words and in art, his is a powerful accountability.