Ligia Lewis is a choreographer, performer, and director whose work is characterized by an eclectic, often dissonant fusion of elements. Deadpan and affect, slapstick and melodrama merge and uncouple in performances delivered with a baroque feel for drama amid stretches of waiting or silence. Lewis’s main medium is dance, and her work is primarily shown in theaters, although also increasingly in museums and video formats — regularly in Europe, and less frequently in the US and UK. Across venues and media, Lewis’s practice emphasizes the limits of what choreography can do and be in relationship to politics and representation. Spoiler alert: not a lot. It’s with this specific awareness that Lewis’s broader project might best be characterized as a fearless reorientation of hope, driven by exploring theater. We spoke about her talents and training, life abroad in Germany, and recent work.

Isabel Parkes: I’m consistently struck by the variety of choreographic styles and references you combine in your work. Can you tell me about this multilayered quality and where you think it comes from?

Ligia Lewis: My love of the theater comes from spending plenty of time in them. My earliest theatrical engagements were performing in Europe with a dance company based in Belgium, and then for various independent choreographers. While I was compelled by some of the investigations that occupied the different artists, I couldn’t find work that fully held my subjectivity or my specific interest in questions of racial embodiment. Nonetheless, being in theaters gave me space and time to dream.

I have also always been very curious about experiments that happen within the theatrical frame, and I’ve remained committed to seeing a lot of work; this has meant I’ve met many kinds of performers and been seduced by a lot of different things. I’ve studied, too — for example taking method acting and mixing it with authentic movement, a somatic practice I’ve engaged with for a long time.

But really, I’ve stayed curious. Exploring genres and gestures like melodrama, deadpan, and psycho-thrillers permitted me to stage my subjectivity in relation to others, and to build work I wanted to see. It also allowed me to work more from intuition, from a psychic space, moved by impulse and urgency.

Through genre- and fiction-making, I’ve been able to speak back to the fictions and truths of race. My work employs hybridity and is always part of a longer process.

IP: Do you mean hybridity in terms of how you combine form with content?

LL: Exactly. When you’re tackling any sort of complex issue, for example critical questions of the body, like I am trying to do, hybridity seems like the only way. It allows me to avoid essentialized narratives. We are as much a product of what we purport to be as what the world determines for us. I think a lot about fiction-making as a way to build outwards from the tropes that made bodies. My work is an attempt to throw thinking into action without providing answers for historical errors that we still feel in the present. I wrestle with expressive concepts and build works out of these concepts.

IP: Can you give an example of the hybridity you’re describing?

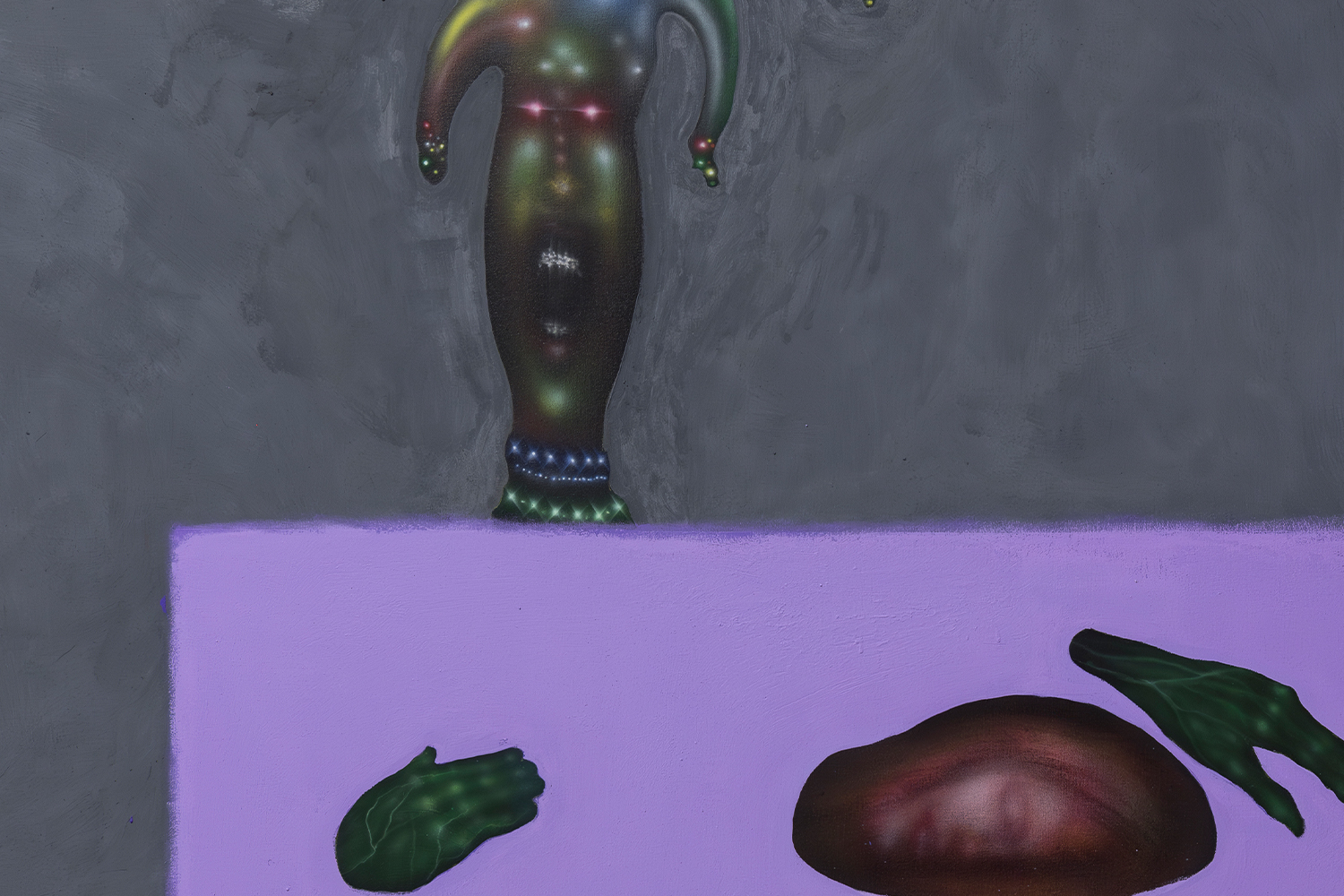

LL: I’m thinking about the hybridity of Adrienne Kennedy’s oeuvre and her work with experimental formats, as well as how, with Kennedy’s work, you often fall in love with a thing that might very well kill you. Kennedy’s work speaks to the complexities, expressions, and horrors of interraciality, as well as of being in a world with a universal concept of being. Acknowledging that my presence disrupts this myth offers me a space to occupy and to depart from. I recognize the theater as distinctly not neutral, which is why my work is saturated in color, sonic landscapes, and movement; I find a slice of possibility in its spaces of friction.

IP: The verb “antagonize” sometimes gets used to talk about the effects your work has on audiences, and I want to probe that loaded characterization.

LL: A way for me to approach some of the things that I love has been to recognize that some of those things cannot necessarily hold me. Early on, during my time in Germany, it became very clear to me that there was something fundamentally missing. In Europe, the danger of a universalized logic — of Europe as the tastemaker and as the home for aesthetics — is everywhere.

That’s not even to mention the whole ghosting of the Afro-Deutsch community, of Black and brown people spread across Europe. This place is the producer of so much historical violence, while simultaneously the site of some interesting aesthetic engagements. Danger lies in erasing the stories that might help us move forward ethically in and through aesthetics.

IP: There’s irony in the fact then that you’ve been told that images in your work are too violent.

LL: Right, or too strong. I’m wrestling with five centuries of historical terror. Representation in and of itself is also not neutral ground. We are all implicated in different forms of violence just through seeing, as seeing reproduces the commonsense logic of racial hierarchy. So, unless we’re actively undoing common sense, then we are continuing the violent script of white supremacy. You know, I feel like a visitor and at times like an impostor here in Europe. I’m just observing, and then continuing to ask questions about what I see.

IP: As you describe the violence of representation, of looking and being seen, I’m thinking of a great quote from New Yorker writer Vinson Cunningham, who described the “superfluity of meaning” in moments of white and Black bodies coming together on stage, playing out for predominantly white audiences. And I wonder if, when critics describe your work as violent, what they’re responding to is a superfluity of meaning. Like, what if we just said that the work of Ligia Lewis was too much?

LL: Right! The question of interraciality is a specific and particularly interesting one. I’m the product of an interracial marriage and I could speak to that, although I try neither to essentialize that experience nor to privilege it. Nonetheless, I just want to briefly speak to the fact that interraciality is something that we are all experiencing. Blackness is everywhere, and as the brilliant Zakiyyah Iman Jackson reminds us, anti- Blackness is everywhere. Interraciality, in part, can disrupt the notion that Black people are the essential opposite of the essential white. But in an anti-Black world, this acquires more troublesome meanings.

IP: As you say this, I’m thinking of how you work with archetypes in your casts of characters.

LL: Absolutely. Like the tragic mulatta who hangs herself in the beginning of Water Will (in Melody) (2018), or the Southern white belle that gets dragged into a horrible monster, opening the piece—archetypes emerge and I try to then disrupt the centralized logic of their characters. I’m always thinking through relations, through characters in relation to one another, because I’m trying to trouble the thing of power that seems to be so essential to the human and that we are all trying to work our way out of. I find that naming the thing is a way to move through it.

I don’t want to deny history, though a decade ago I think I was trying to do that. Now I’m ok sitting with all the mess that this world has created and simultaneously trying to dream up other possibilities. That means high stakes, much higher than just inclusion.

I’ll make jokes about which archetype has to die in a constellation of characters as a way to explore what that means when you say it in the frame of a theater. I want to attend to the fact that we are all organized around whiteness, just as we’re all touched by Blackness and anti-Blackness.

IP: As we’re talking about this, Ligia, I’m thinking of a moment in Still Not Still (2021) in which Cassie [Augusta Jørgensen] looks out at the audience and starts counting. Can you talk about that moment?

LL: Right. I asked Cassie to count all the white people, which is who I suspect are going to be our public. And this is because we know it in the history of theater. That moment is a way to turn around and be like, “We see you. Oh, one, two, three…” And before she does, she also says to Damien, her other white counterpart, “Kin. Good job.”

IP: In other scenes, Still Not Still does the opposite. It disrupts rather than acknowledges our complicit understandings of race and sexual relations.

LL: Yes, it heightens the violence of these and other visual marks. For example, at one point, when I ask Cassie to say, “I’m not your average white girl. But for a second, I thought the world was mine,” I am speaking back to white feminisms.

In those moments of performance, I’m exploring the thing of passing in gender and in race. I seek possibilities for coalition and entanglement, without a doubt, but I also trouble kinship, much in the spirit of Hortense Spillers. Kinship was the very thing that was removed from Black folks in the west, from the captive subject, right? In that moment I am getting at the difficulty of coming together.

IP: There’s a quality to Still Not Still that’s world shattering and world making.

LL: In my work, the commons becomes not troubled but sought after; collectivity is challenged as well as enacted.

What are the stakes in disrupting recurring images of Black death? This question is fundamental to Still Not Still. The final soliloquy, performed by Jolie Ngemi and me, reminds us of humans’ death drive. In Corey [Scott Gilbert’s] final entrance, after three loops of the Western macabre replete with endless dying and dancing, house lights come up and the auditorium is filled with Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell’s song, “You’re All I Need to Get By.”

This final moment for Corey—the moment his fall into his grave is disrupted—is the moment that I ask our audience how we might imagine a different world.

It’s not for me to necessarily create one, but to create the possibility of thinking about what’s at stake in creating one. It’s to suggest that we all must be active participants in that act.