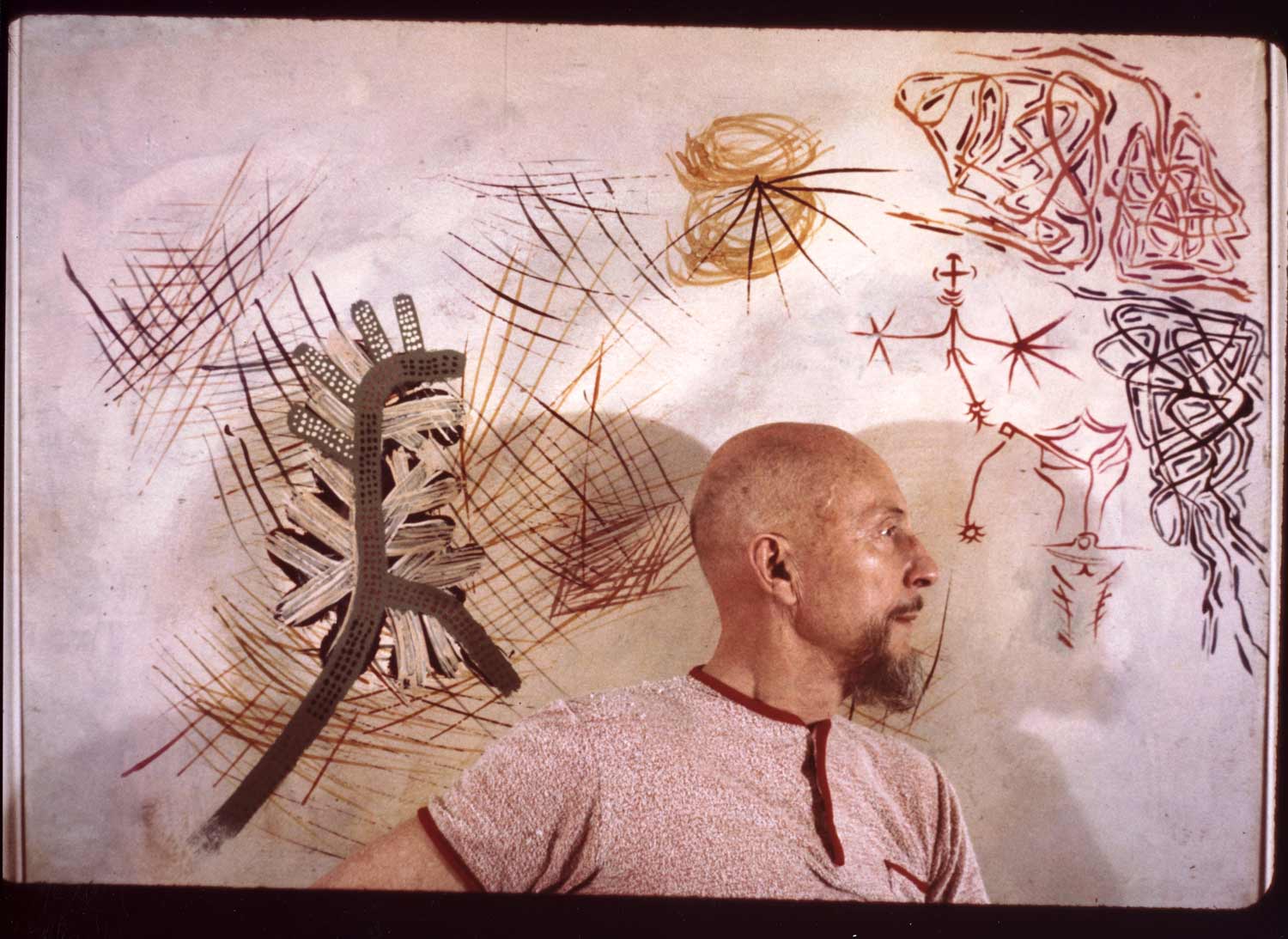

Light, noise, and motion form the nucleus of the career of Len Lye. This exhibition, spanning his early adulthood forward, makes a compelling case for much more than the artist’s contributions to experimental filmmaking. Born in New Zealand with time spent in Australia before moving to London and eventually New York, Lye’s earliest interests exhibit the same problematics as his European modernist peers. A desire to harness external indigenous culture meets the organic in his earliest film, Tusalava (1929) — an animation of dancing forms alluding to microscopic fertilization and tribal imagery. Like all of his time-based work, it seems wildly ahead of its time.

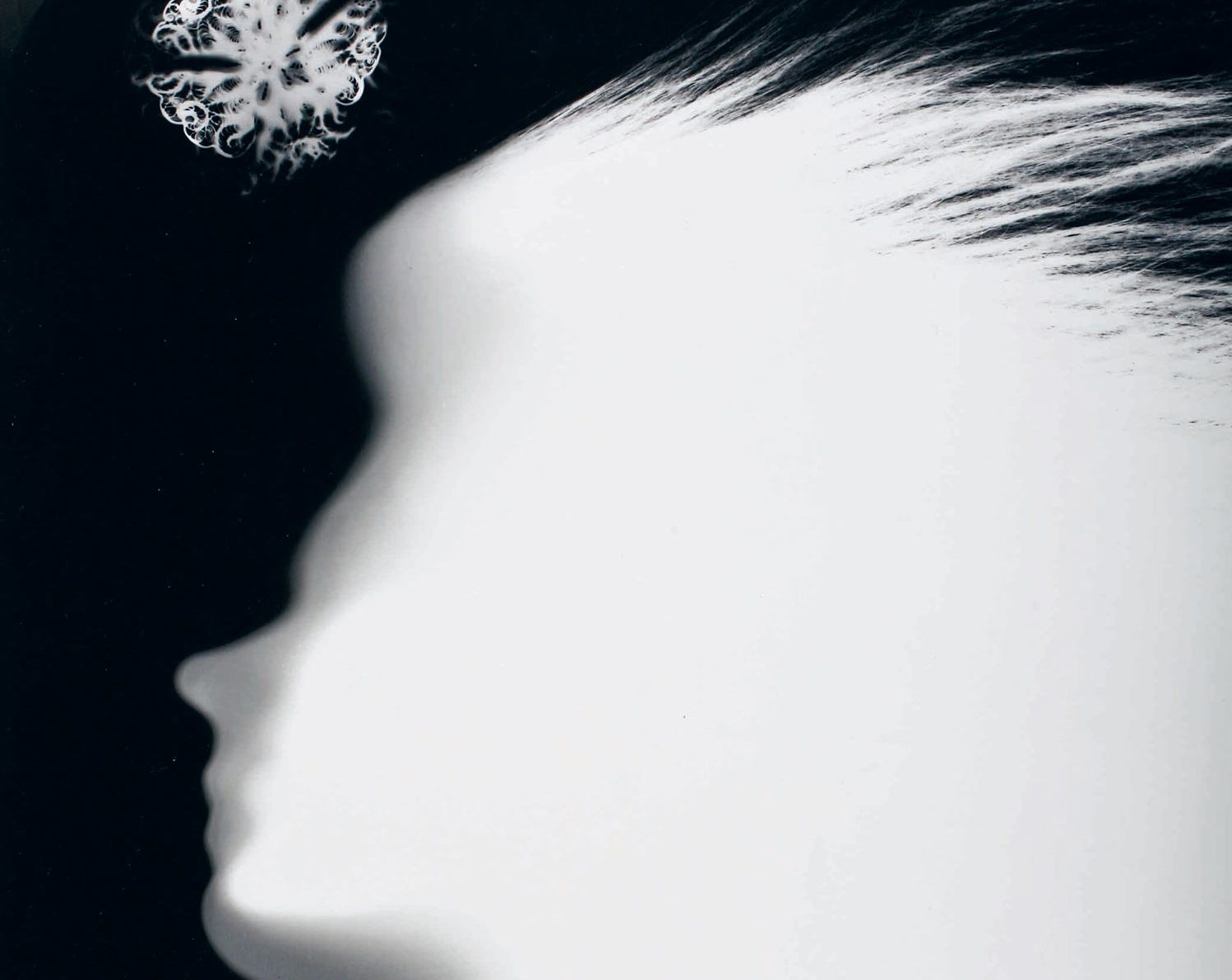

Photograms like Self Planting at Night (Night Tree) and Earth Magnetic (both 1930), previously exhibited in major Surrealist exhibitions, are brilliant and a privilege to view. They combine biomorphic shapes that recall river systems, cell cultures, and internal universes in a way that feels concise yet ever-expanding. Near identical motifs appear in batiks, the cover of a hand-printed book, paintings, and later photograms. Lye’s commitment to returning to his own ideas and imagery across decades is a central aspect of his career.

Nearly all of Lye’s cinematic work is on view, strategically interspersed so as to prevent both internal competition and external fatigue. Kaleidoscope, A Colour Box, and Rainbow Dance (all 1935) were commissioned for commercial reasons, yet all fulfill Lye’s artistic intent. Vibrant, musical, and near psychedelic, they are shown at the giant scale they originally would have been presented at when screened in cinemas and seen by millions. Rainbow Dance, in particular, is shocking for how much it anticipates Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940), early MTV music videos, and Apple’s silhouetted iPod commercials from 2003.

Lye’s later kinetic sculptures are mixed, but the range and amount exhibited is staggering. Grass (1965) resembles its title with long stainless-steel wires slowly rocking back and forth. It is graceful both visually and audibly, the opposite of Storm King (1964) whose metal protrusions jack back and forth rapidly, fuck-joke style. But it’s Universe (1963) that shows the potential magic of his materials. A large loop moves amoebically left and right, gently striking a hanging ball and adding musical chance to a hypnotic visual. All show a desire to continue cinematic explorations in the plastic, as the light striking his metal surfaces becomes a near-physical dancing form.

The final room introduces plans for never-completed monumental projects and dreams. Universe Walk (maquette) (1960s) was conceived for Death Valley, a singular massive experience of magnetic movement, warping noise, and twisting metal. Seemingly somewhere between hell and Heizer, nearly all the elements exist elsewhere in the exhibition in a variety of scale. It’s this piecemeal extension of movement, sound, and image over time that define Lye’s vision. It’s a full career worth lingering over.