The work of Latifa Echakhch is refreshing proof of how art can be communicative and socially educational without being patronizing or exploitative. Echakhch’s sculptures are very elegant and delicate, but the viewer shouldn’t let her discreet sensitivity in examining issues such as religion, geography and personal and collective history be deceptive. The visual and conceptual power of her combination of minimalism and romanticism is potent, and what comes across is a fundamental belief in the dignity of her subjects, even in her most severe critical moments. This achievement is largely ascribable to Echakhch’s gift for taking the best out of the materials she chooses. Ordinary items like sugar cubes, fragmented carpets and broken tea glasses are converted into silent testimonies of sentiments like nostalgia, anger and a sense of disheartenment towards failed utopias.

Part of Echakhch’s art seems to adhere to Naomi Klein’s theory about political battles moving to more sophisticated grounds and the necessity to reinvent the instruments for the fight. Echakhch’s acknowledgement of past forms of political activities is respectful and passionate, but is inevitably shaken by the implicit consideration that when it’s tribute time, it’s also time to move on.

Speakers’ Corner (2008) is an emaciated wooden soapbox that alludes to the famous Hyde Park square where people could step on improvised podiums and freely address bystanders on whatever topics.

Almost a readymade, it is a testament to a time when the corner was one of the few spots of democratic speech and freedom before street preaching and the Internet transformed the whole scene into an empty exercise.

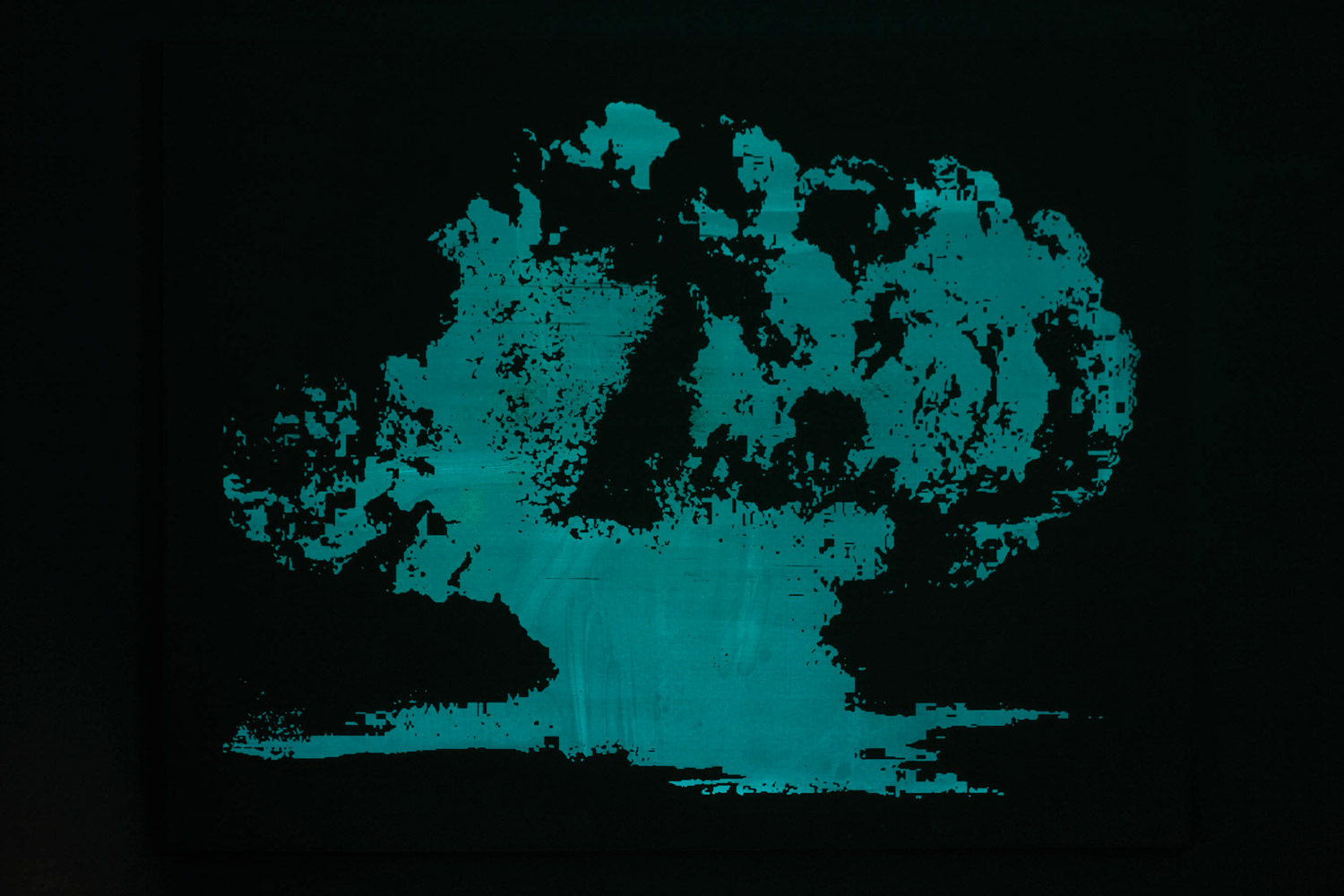

For Each Stencil a Revolution (2007) is an environmental sculpture named after one of Yasser Arafat’s aphorisms. It refers to the days of political leaflets and how these rudimentary pieces of carbon paper could be effective weapons for the divulgation of political credos. Glued on the wall and washed with splashes of solvent, the paper sheets generate a series of drips and pools and are coupled with a set of old rubbers dispersed through the room, suggesting a degraded suburban area and creating a stark contrast with the spiritual, almost ethereal quality of the surrounding deep-blue painted scenario.

The removal of contents and the consequent re-contextualization of the container is a process by no means unusual in Echakhch’s work. Fifty Fifty Fantasia (2007) is a group of intersected flagpoles bulging from the wall. Stripped of the banner that marks their identity, they engage an ambiguous dance that could be interpreted as either a moot brawl or a utopian act of unity.

Perhaps Echakhch’s ability to express complex ideas by simple gestures is still best represented in one of her early pieces, Snow in Arabia (2003). Consisting of a detuned TV monitor with a cube-shaped strip of black tape glued at the center, it testifies at once the agitation of manhood in its spiritual quest, the detached authority of religion and how this is pictured by the world’s most powerful and controversial media.