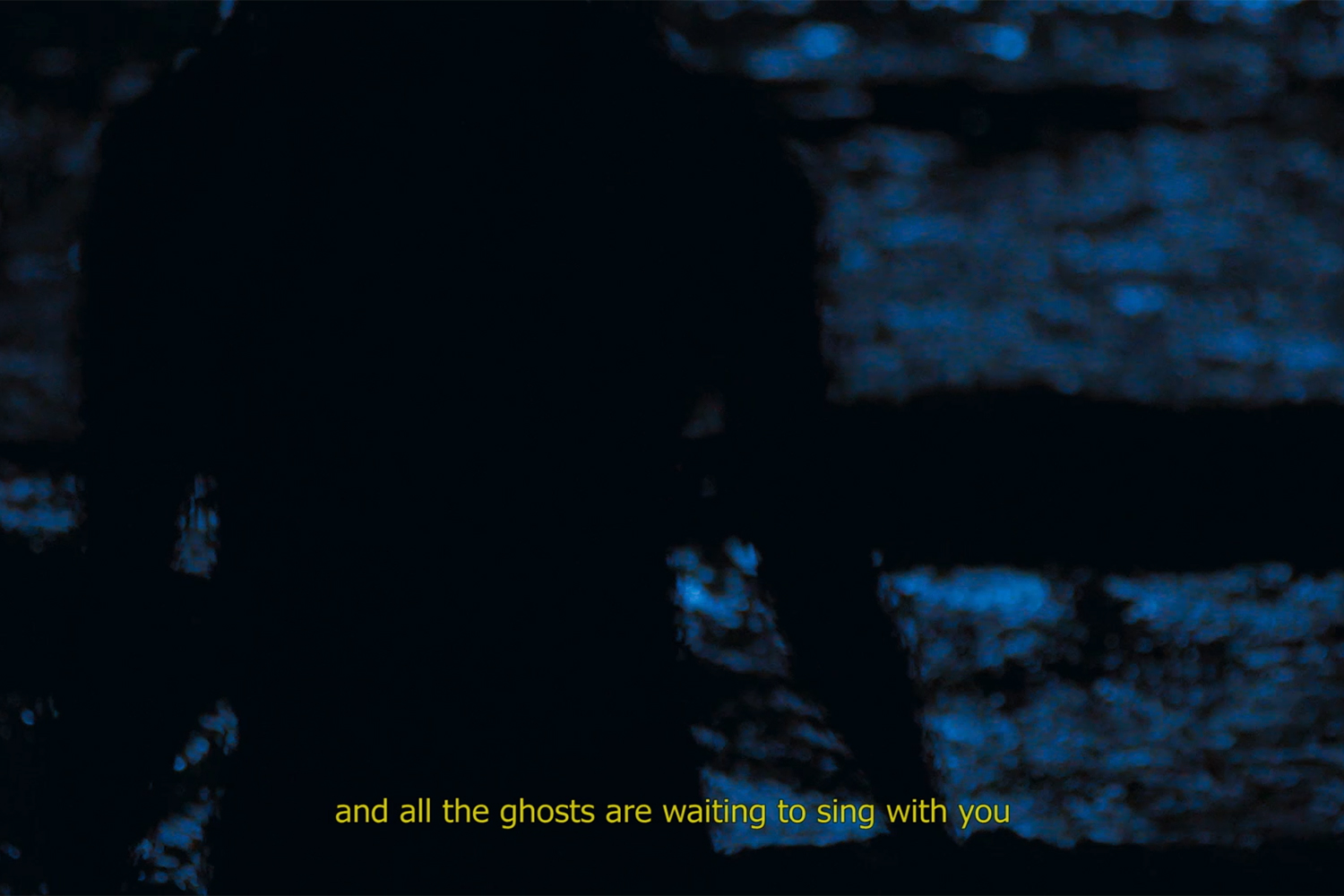

“Follow my voice,” urges the shaman in the beginning of Korakrit Arunanondchai’s video Songs for dying, 2021 (co-commissioned by the 13th Gwangju Biennale, Han Nefkens Foundation, and Kunsthall Trondheim). The camera follows an elder woman wearing a ceremonial garment. The colors of the images are tinted blue as if in a dream, and the medium’s voice is represented by an abstract drone-like sound, her words only legible by subtitles. She goes on: “All the ghosts are waiting to sing with you. Your consciousness is scattering, let it become light. You can be everywhere in any time. And soon be everything.” Cut to a group of people encircling a tree, their arms swaying high in the air. As the skies light up with the rising sun, the shaman is descending to a beach where burned candles are arranged in a circle made of dirt. Where there were people just a moment ago, now there is only a toy rabbit left looking upon the scene.

In Korakrit’s universe, subjectivity is distributed among many — among all. There is no single protagonist with a stable “I,” but personhood can move from a human to a tree to a ghost, or inhabit all of them at once. In the shaman’s words: “You can be everywhere in any time.” Perhaps more fitting than the word “universe” to describe Korakrit’s world is the word “ecosystem.” I consider ecosystems as not limited to physical entities understood as “living” in the Western sense, but encompassing all things existing, both living and nonliving, both technological and organic, both material and spiritual, both past and future, both those we can know of and those we cannot fathom. In Korakrit’s videos, these divides come undone for continued process and change, decomposition and renewal. In our present moment of intensified grief for people passing due to a deadly virus, and of the deepening dawning that the Global North is not immune to social disaster or the climate catastrophe that it is largely causing, his videos offer both connectivity across material and spiritual divides, and ways of mourning. In his all-embracing ecosystem, the specificity of experience and of local histories is the root of wider-reaching ramifications. His videos do not attempt to unify and annul differences, but seek to consider them in an ever-changing network of shifting perspectives and essences alike.

In the next scene in Songs for dying we find ourselves in a hospital room. We see two hands caressing one another, one old and one young. A voice speaking Thai instructs: “Now we will practice dying. Try to imagine yourself sleeping alone on a bed in a dimly lit room. Next to you is a machine for your heart rate… In a few minutes your last breath… How many lives do I have to live to see you again?” In Korakrit’s most personal work to date, we witness the death of his grandfather, who has appeared in many of his previous videos. The disembodied voice continues as it guides us through a meditation on the process of dying, followed by a crescendo of electronic music and a cascade of images splicing together people holding up flashing cell phones, shots of a market place, the artist’s grandfather playing piano, an eye, a transparent plastic bag filled with organs, elements from Korakrit’s previous videos, and footage recorded at a memorial site on Jeju Island in South Korea. The work was commissioned by the Gwangju Biennale, Han Nefkens Foundation, and Kunsthall Trondheim, curated at the latter by my colleague Katrine Elise Pedersen. The Jeju massacre in 1948 was largely labeled as a communist uprising and the Korean state prohibited it from being discussed for almost sixty years. It was only through the work of shamans that the atrocities could be addressed, obliquely. The shamans became the mediums able to pass the threshold between what is permitted by state power and what cannot be addressed, between official reality and trauma. They became vehicles for grief and mourning.

A third main layer of the video is made up of the pro- democracy protests in Thailand. Similar to the shamans, who after the Jeju massacre mediated suppressed history, the protestors rely on proxies to be able to address the military-monarchy ruling class. By law, the Thai king cannot be spoken to, let alone criticized. To bypass this prohibition, demonstrators avail themselves of stand-ins such as the yellow inflatable rubber ducks that have also been used in protests in Hong Kong, or the three-finger salute from the Hollywood movie series Hunger Games, signaling defiance to authority. These objects and gestures are able to channel dissent while their signification remains ambivalent, thereby circumventing illegality. Throughout Korakrit’s ecosystem, objects and symbols transubstantiate and extend beyond their time through a distributed consciousness that outlasts their own existence.

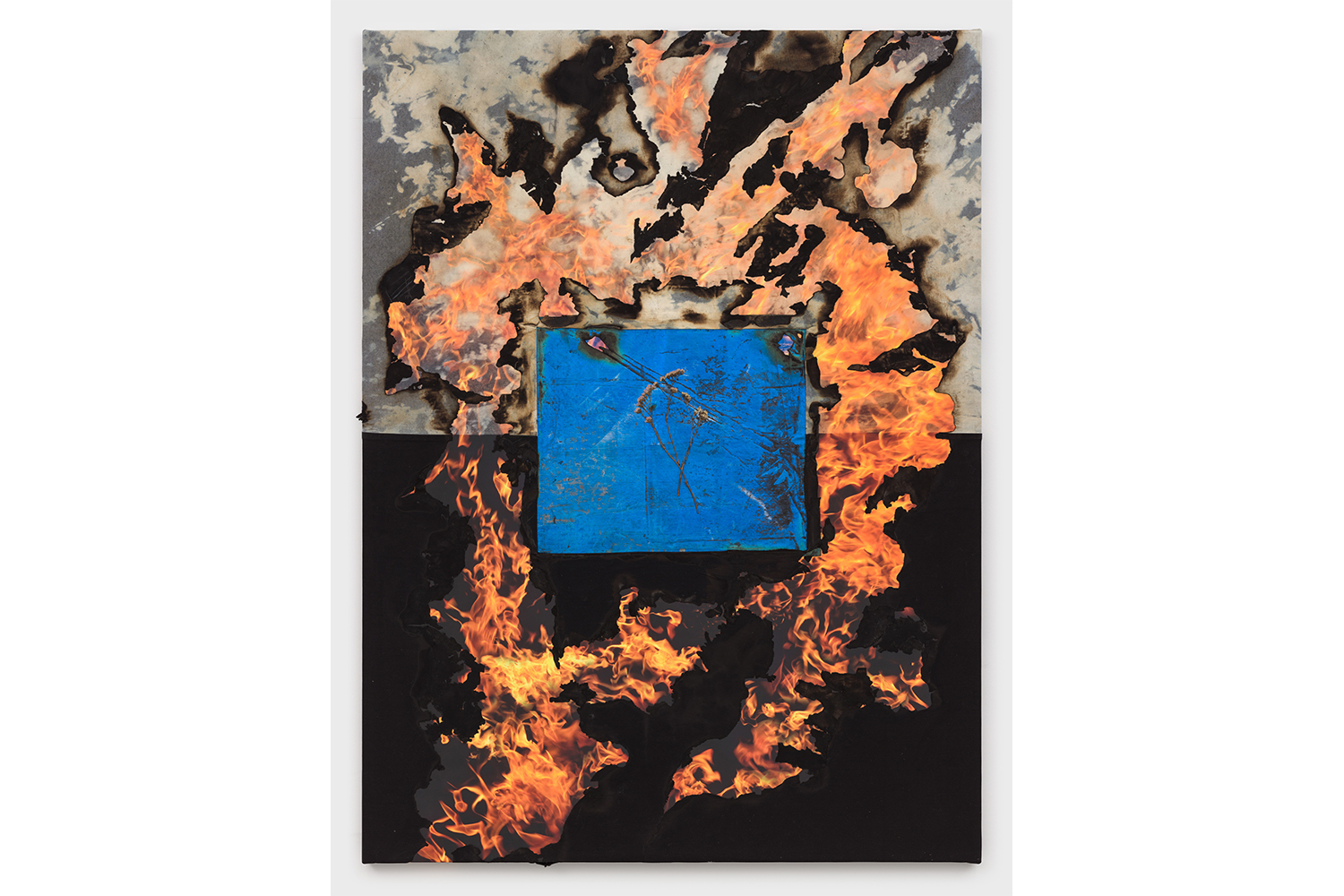

Addressing one thing through another, in fact channeling its very essence however transformed, speaks to the role of threshold objects in Korakrit’s videos. Taking on the function of portals, threshold objects recur throughout his practice. They can take the form of a shaman, of fire as an element of transformation, or of a movie. In previous works such as No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5 (with Alex Gvojic and Tosh Basco, 2018, commissioned by Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève for the Biennale of Moving Images), Korakrit explored the phenomenon of Ghost Cinema, in which films are passages between the physical world and its spirit counterpart. Ghost Cinema originated in Thailand during the time of the Vietnam War, when 16 mm projectors arrived in the region with the American GIs. In Thailand, many of the soldiers were stationed in Udon Thani, a strategic location in the northeast where recently a secret CIA prison was discovered. Key technologies for the military-industrial-media complex, the 16 mm projectors were used for the GI’s entertainment as well as to spread anti- communist propaganda. In acts of psychological warfare, the Americans also used the apparatuses to play abstract sounds and lights in the forest as attempts to scare off villagers and guerilla fighters. After the imperialist forces withdrew, they left the projectors behind. These were subsequently utilized by traveling film projectionists, and in the late 1980s, an incident occurred where an outdoor screening was seized by the serpent divinity Nāga as it craved an evening of cinematic entertainment. The event gave rise to shared movie screenings for humans and ghosts, organized by projectionists as well as monks, in which the projected film becomes a threshold object or a passage for the living and the dead by connecting both registers of worlds. In No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5, the Nāga is channeled by Korakrit’s longtime collaborator Tosh Basco, whose throbbing body, painted in green, signals the shifting of shapes, substances, and meanings at the core of the work.

In the video, the spectral movie screenings are further interwoven with the spectacular rescue of twelve boys and their football coach from the Tham Luang cave in northern Thailand in 2018. In this hypermediatized event, the unlikely allies of Thai military, self-described technoking Elon Musk, monks, and spirit mediums supported the rescue operation while each seizing the event for their own PR purposes. State power, media, technology, spirit mediums, storytelling, capitalism, and globalization here were bound together into a complex material-spiritual assemblage. A voice in the video tells us: “Words make worlds.” This is true for legal systems as much as creation myths, storytelling, and propaganda. Korakrit’s videos ask us what worlds we want to create — worlds made up of complex ecosystems comprising politics, technology, and spirits alike.

Ecology in its more established sense is addressed explicitly in the video There’s a word I’m trying to remember, for a feeling I’m about to have (a distracted path toward extinction) (with Alex Gvojic, 2016, commissioned and co-produced by the Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art with support from I LOVE YOU The Project) — specifically ecological disaster and extinction. The work centers on a new fictionalized planet in the star system Alpha Centauri, the artist’s older brother’s wedding, Korean American rapper Yen Tech, and a rat — a species likely to survive apocalyptic events due to the rodents’ fecundity and relentless survival instinct. As much as the elements in each of Korakrit’s works connect — in this case bringing together divergent ecologies of distressed nature, space colonization, rituals celebrating love, science fiction, and apocalypse — his works are also tethered to one another through themes revisited or imagery appearing again and again. In Korakrit’s latest video Songs for living (with Alex Gvojic, 2021, co-commissioned by the Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst and Kunstverein in Hamburg with support from FACT, Liverpool), several characters and scenes from previous works resurface, for instance the shaman from Songs for dying, now standing inside the ruins of a burned building. A gang wearing black wings (or is it a group of bird-angels with human faces?) zoom through New York City on one-wheeled electric scooters at night, while a group of people ecstatically dance around a fire, and we follow a sea turtle swimming along an underwater pipe in sepia-tinted waters. The linearity of time and unidirectional progress, which is complicated in all of Korakrit’s works, is here more explicitly thrown into high relief as we watch a bird burning in reverse on a fire, and people walking backward into a body of water from which they seem to have emerged just a moment ago. They are clad in denim jeans, a material that recurs in Korakrit’s videos and lends itself as a surface to his paintings. Blue jeans are a transnational symbol of freedom emanating from America, but also emblematic of the working class, imperialism, and cultural hegemony. The plant from which the indigo color used to dye jeans is derived is entangled in colonial histories and brutal working conditions, such as in El Salvador under Spanish colonial rule, when Indigenous populations were forced to labor and were largely decimated. As with the three-finger salute from the Hunger Games series, appropriated by protesters in pro-democracy movements, the jeans here suggest that meanings can shift and that history is not equivalent to progress. Walter Benjamin’s “angel of history” would be too unequivocal an interpretation. Much rather, Korakrit’s reversals and recurrences seem to suggest that death for one means life for another on scales both large and small, that darkness gives shape to light, as Octavia E. Butler might say, and that Gaia connects all beings. We may not survive ourselves but that doesn’t mean that life will end. A rat or a turtle may know the way.

In Songs for living, the linearity of time gives way to a deep interwovenness of events and entities. An electronically distorted voice declares: “The word ‘is’ has no meaning.” It continues, “Their bones will turn into coral resting and waiting for them on the other side of time.” When Korakrit’s grandfather passed, his remains were scattered in the ocean together with flower petals, as seen in Songs for dying. According to the artist, the remains looked like coral that longed to be returned to the sea. The sequel of the video, Songs for living, culminates in chanting voices repeating the words “pieces of coral, pieces like bones.” In Korakrit’s ecosystem, all registers talk together like the roots of a tree, allowing it to connect and communicate with others. And from the tree, a new body may grow. In Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea series, the word for beginning is also the word for end. And the word for end is also the word for beginning.