The etymology of the verb “desire” refers to the disappearance of a star from human sight — desidere in Latin. Katharina Grosse’s exhibition “Shifting the Stars,” currently on view at Centre Pompidou-Metz, explores the idea of linking desire and the scale of seeing through an examination of the notion of the sublime, articulating color and painting in relation to the human body and architecture. Its four monumental installations are spread from the Centre Pompidou’s forecourt to the main entrance hall and the ground-floor gallery, where they interact intensely with the architecture of Shigeru Ban and Jean de Gastines. All the installations — except for Untitled (2024), which features uprooted trees and folded canvases — use sprayed colors in expansive proportions, pushing the limits of human perception. The works offer generous reflections on landscape and color, providing an extraordinary experience of scale and spatiality.

The first wonder of the show is the reinstallation of The Horse Trotted Another Couple Of Metres, Then It Stopped (2018), originally conceived in Sydney and here overflowing the museum’s Grande Nef. The title of the exhibition alludes to the displacement of this work from one continent to another. The spectacular scale of the suspended, multifolded, and sewed canvas transforms it into a landscape to be traversed. Grosse creates a meditative and immersive experience, encouraging viewers to walk on it and perceive its angles and folds as spatial creations. The enveloping quality of the work makes it resemble a suspended, enormous yet humble canvas bag when approached from the outside — like a nest, a matricidal membrane, or a basket — that echoes the form of the Grande Nef.

In Untitled (2024), the other installation presented inside the gallery, the artist employs a more sober language. The site-specific nature of this work, which features oaks and hornbeams from the neighboring Vosges region, selected in consultation with the National Forestry Commission, creates a thoughtful balance with the color splash of the other installation in the same space. The elegant folds of the canvas surrounding the tree trunks and the clusters of roots question again the notion of landscape. Grosse’s work enters into direct dialogue with natural elements linked to the sublime — such as tempests, storms, and earthquakes — suggesting these absent narrative forces could have caused the brutal uprooting depicted in the installation.

Conceived and built in the artists’ bedroom in Dusseldorf, The Bed (2004) is generously offered to the public at the heart of the entrance hall, where it faces large windows that expand the work’s scope. The partially bombed room and its quotidian objects become a testimony to discarded intimacy, with folded sheets, girly shoes, piles of books, items of clothing, and cardboard boxes. Here details matter, such as the splashed spines of Virginie Despentes’s Vernon Subutex 2 and 3 (both 2015) appearing among a very eclectic pile of books by French authors, from Henry de Montherlant to Jules Romains and Zola’s meta-work L’Oeuvre (1886). The references seem to expand like the possibilities offered by an intimate space in exile.

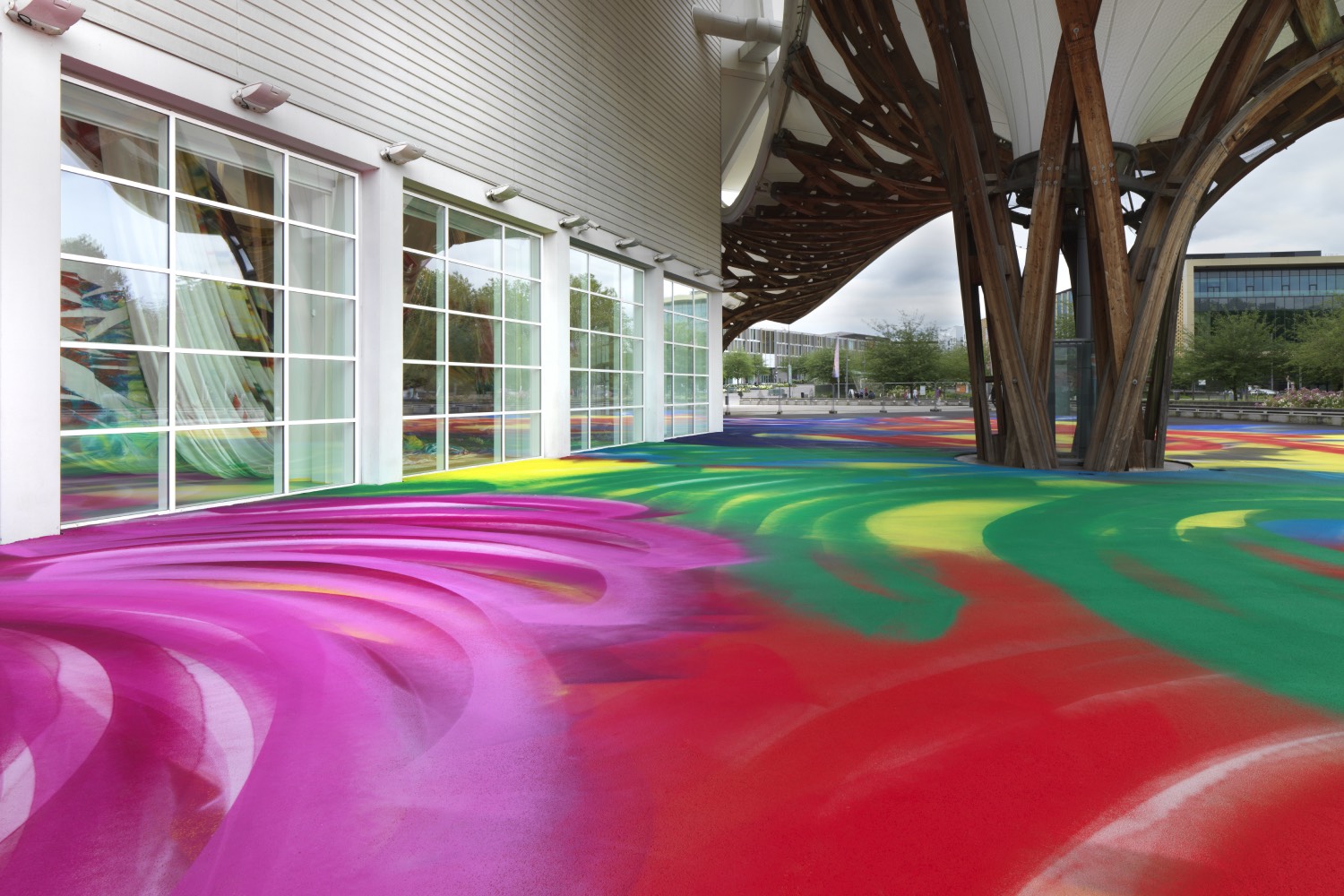

In the courtyard of Centre Pompidou is Shifting the Stars (2024), a vast in situ horizontal floor painting. Its grounding quality and immediate joyfulness are evident as passersby walk or bike over it. Splashes of vivid colors unconsciously evoke a hopscotch pattern without any imposed path, reflecting the creation of communal spaces with a sincere, earthly quality. This titanic layering of sprayed colors disperses energy throughout the surrounding area.

Where is the sublime born? What is it born from? The exhibition seems to suggest that it emerges from a recognition of the tension between nature and artifice. The transcontinental conversation between Europe and Oceania serves as a metaphor for an earthy scale, akin to the architectural scale that has fascinated Grosse since the beginning of her career. This belief in the potential of every shape of the world is evident in works such as the eggs she painted as a child in 1973 or Atom Outside Eggs (2007). One might also recall Grosse’s series of mural paintings, “psychylustro” (2014), along Philadelphia train tracks: seen from a moving train, the landscape and murals are perfectly framed by the train’s windows, expanding through daily journeys, speed distorting the scale of perception as part of the work. Grosse raises questions about our capacity to perceive motion in relation to our own bodies and to our ways of moving through the world. Our journeys are like those of the stars; color is a means to create commonality, and achievements are promises.