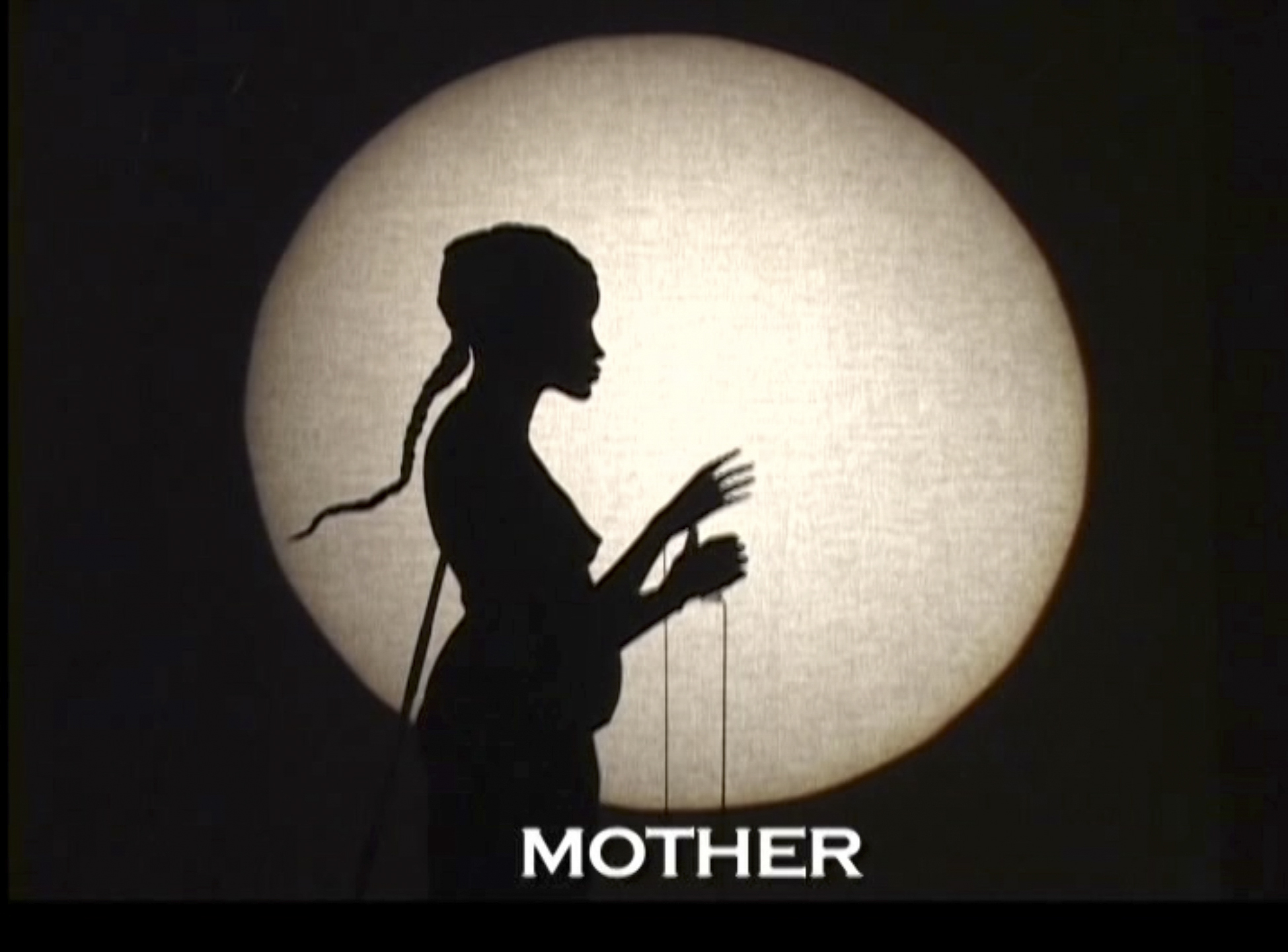

Coinciding with the artist’s Tate Modern Turbine Hall commission, Sprüth Magers London presents the first retrospective of Kara Walker’s films. In addition to notes, storyboards, and wall-mounted puppets, the exhibition, devised by curator and writer Hilton Als, includes eight color and black-and-white videos set in the antebellum American South during the time of the transatlantic slave trade. Acted out with small black paper puppets and silhouettes, the films reveal how narratives and cinema produce and reproduce African American history and trauma.

In Walker’s cut-out characters, black and white become caricatures — they’re reduced to their most basic, base form. Bulbous lips and bulging rumps. Floppy long fringes and pointy noses. Like the silhouette, the stereotype “says a lot with very little information,” Walker has said.

8 Possible Beginnings or: The Creation of African-America, a Moving Picture by Kara E. Walker (2005) is based on Song of the South (1946), Disney’s Uncle Tomish depiction of the southern states after the civil war. In Walker’s interpretation, a white boy threatens to have Uncle Remus whipped if he doesn’t tell him a story, reflecting the way Hollywood’s founding fathers reinforced black mental servitude, long after the abolition of slavery.

Other films invert the stereotyped hyperactive black male libido, seen as a vile threat to white women’s honor and purity. In Fall Frum Grace, Miss Pipi’s Blue Tale (2011), the governess attempts to seduce a plantation worker. He rejects her advances, most likely for fear of accusation of rape. She eventually ensnares him under her mangrove-root-like dress, but they’re caught by the master, who in a fit of jealous rage mutilates and murders the black labourer. Conversely, in Six Miles from Springfield on the Franklin Road (2009), a film derived from historical, first-person testimony, a gang of white men subject a young black girl and her family to sexual violation, murder, and arson. The contrast in narratives exposes the way legal protection favours white women, a disparity still seen today in the disproportionate number of black men killed by US police, powerfully shown by Arthur Jafa’s video Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016).

Earlier in Fall Frum Grace, perhaps in a dream, the master breaks into tears after terrorising a black man, reflecting a contemporary form of white guilt that often comes with a tendency to appropriate or lay emotional claim to black trauma. As Zadie Smith writes in a 2017 article for Harper’s Magazine titled “Getting In and Out: Who Owns Black Pain?,” many things belong to black people: “our voices, our personal style, our hair, our cultural products, our history, and, perhaps more than anything else, our pain. A people from whom so much has been stolen are understandably protective of their possessions, especially the ineffable kind.” As with the artist’s monumental Tate installation Fons Americanus, a giant fountain that critiques the brutal legacy of the British Empire, white viewers of the Walker’s films are split between well-intentioned empathy and carefully measured deference. I can’t speak for black audiences; that is for a black critic to do.