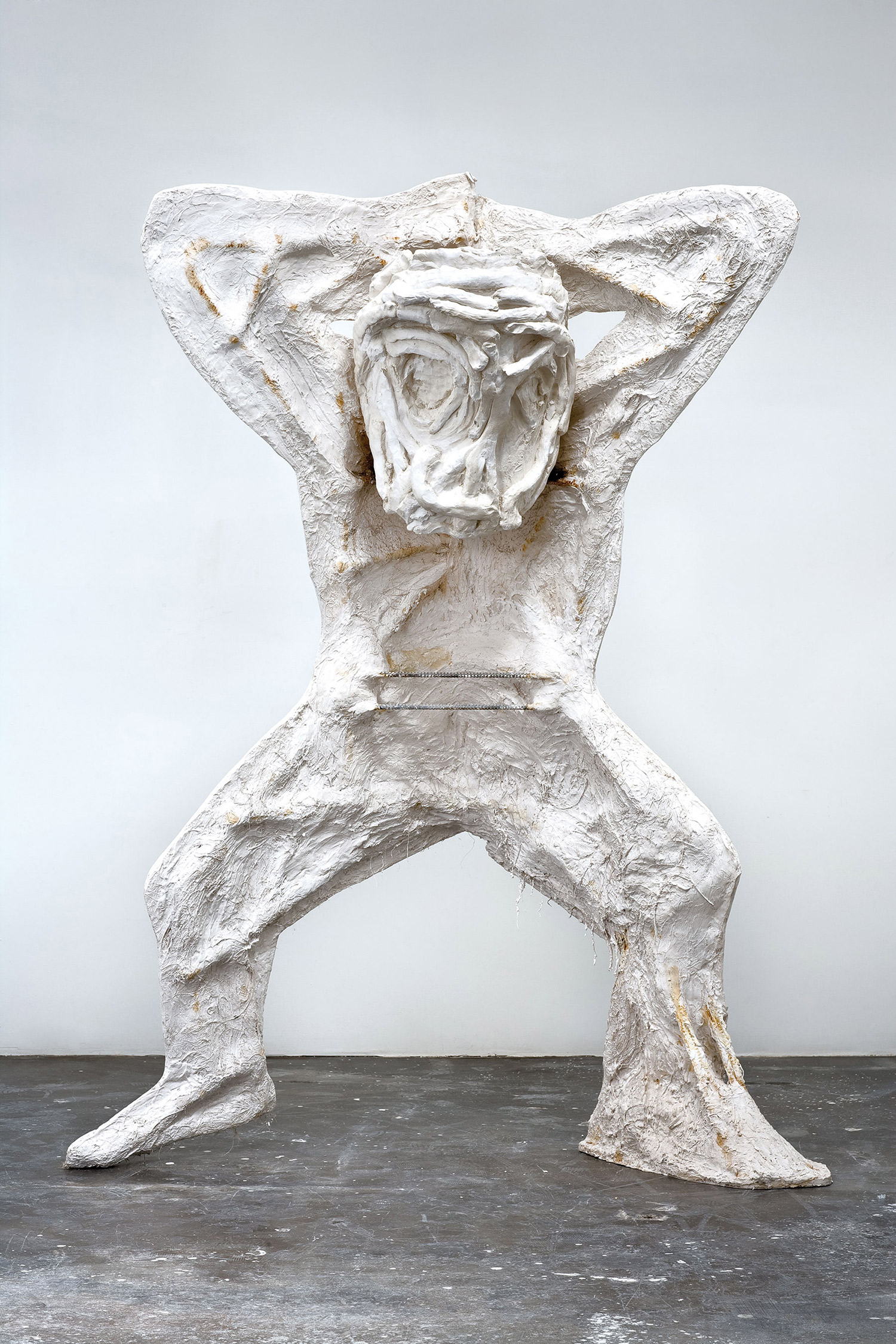

Family Dollar (2009). Courtesy the Artist and Master Piper, London. Photography by Anna Arca.

In his introduction to The Metastases of Enjoyment (1994), the philosopher Slavoj Žižek recalls an outraged student taking him to task after delivering a lecture on Hitchcock to an American campus in 1992. The student railed at him for daring to talk about Hitchcock while there was a war raging in the Balkans. Žižek realized he had unwittingly violated a ‘silent prohibition’ — he was behaving like a ‘normal’ American rather than a ‘victim’ of war. He explains: “The unbearable is not the difference. The unbearable is the fact that, in a sense, there is no difference. There are no exotic, bloodthirsty ‘Balkanians’ in Sarajevo, just normal citizens like us. The moment we take full note of this fact, the frontier that separates ‘us’ from ‘them’ is exposed in all its arbitrariness, and we are forced to renounce the safe distance of external observers.”

Just like Žižek, British painter Justin Mortimer crosses the line that divides ‘us’ from ‘them.’ His most recent body of works to date: “In Your Own Village” (2009-2010), engages with the horrors of war and brutality in a manner that forces us out of our comfort zone and into the realm of the uncanny. Horror becomes especially hideous when it occurs in homely or idyllic settings, and the stages Mortimer crafts for his representation of conflict are often benignly pastoral northern European landscapes. In Your Own Village (2009) depicts a traditional white-wall and timbered, red-roofed building nestled in a field across a river, while Depot (2009) features chocolate-box alpine villages. Take out the imagery of war — the mutilated naked corpses and the hooded, hanging figures — and you could be touring through northern France, Austria or Germany on a family holiday. This though is the point: it could be anywhere, it could be a day out; it could be home. Mortimer is constantly underlining that “there is never ‘them,’ only ‘us.’” Lest we fall into the trap of associating ourselves with a particular time period, race or geographical region, the artist deliberately selects material for his paintings from diverse sources and periods of history: Europe in the First and Second World Wars, the Balkans, Russia, the Middle East, Rwanda. The imagery is extraordinary in the worst kind of way: the cosy house depicted in In Your Own Village is on fire, and in the center of Theme Park (2009) a man hangs from a makeshift noose while a young man clad only in swimming trunks looks on. Yet through a process of re-assemblage — interweaving horror with nature and figures and buildings derived from his own holiday snaps — Mortimer draws us in. The acts of barbarism become part of real life: atrocities perpetuated in serene surroundings by normal people on other normal people who somehow became the ‘other’.

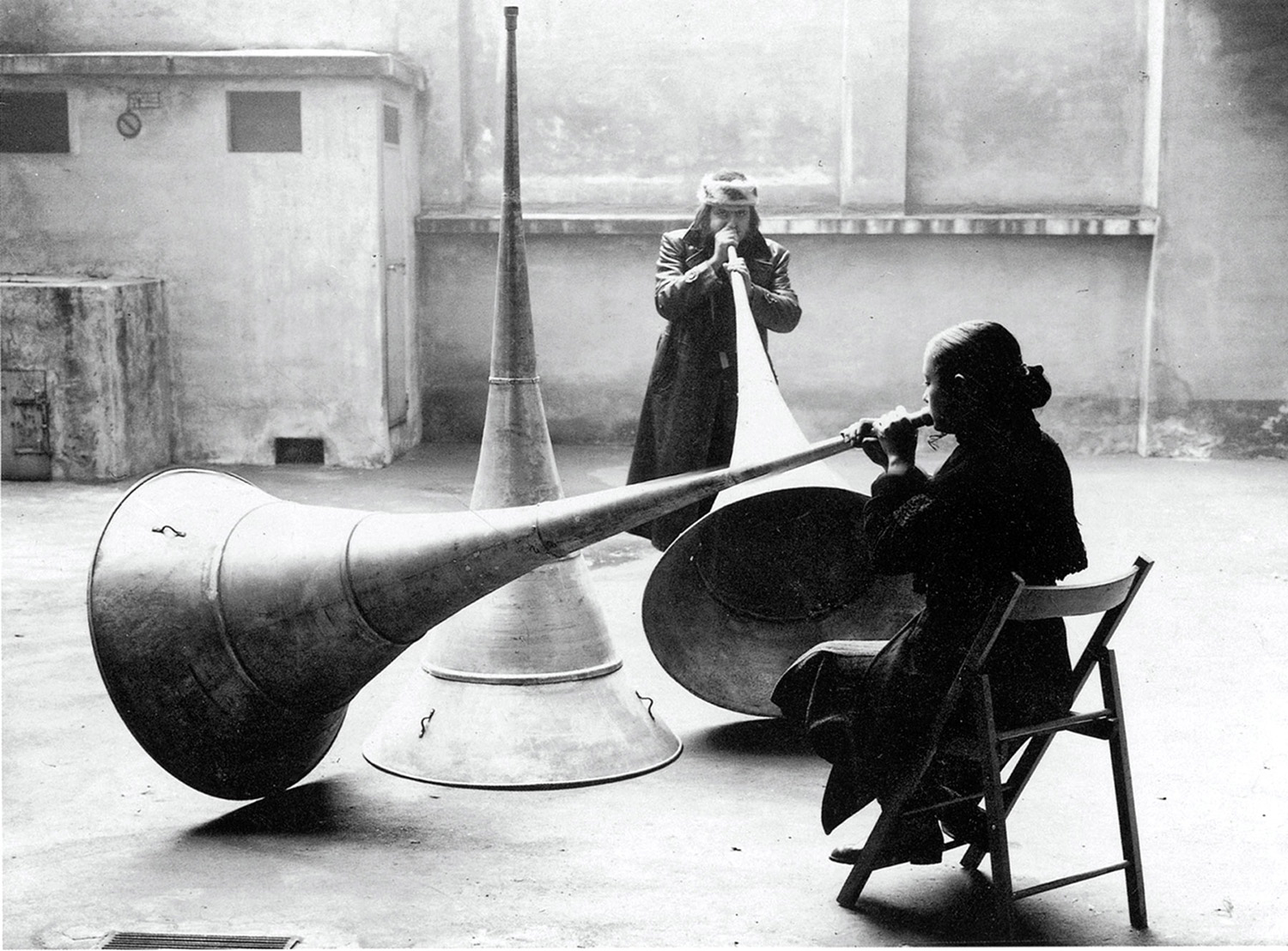

Cleaners (2009). Courtesy the Artist and Master Piper, London. Photography by Anna Arca.

In the wrong hands, Mortimer’s subject matter could become sensationalized. Prurience or a voyeurism for horror might creep unbidden into the work and destroy the fine and moving sensibility of the paintings. Alternatively he could become mawkish, belaboring the subject and falling into the trap of sentimentality that caught some of the Pre-Raphaelite painters late in their careers (the viewer is bound to compare Mortimer with for their shared attention to detail, close observation of nature and sensitive rendering of form and emotion). Mortimer’s paintings are successful, though a work such as Theme Park pushes things so far with its disturbingly eclectic arrangement of imagery as to risk catapulting the viewer out of the conceivable and consistent universe the artist has taken such pains to create. They are arrestingly beautiful — painted with a virtuosity and control that serves to sharpen the impact of the dramatic subject matter — yet even more than this, they are motivated by the artist’s deep compassion for the human condition. This is clearly conveyed by the tender, scrupulous attention he pays to the human form. Each limb, no matter how damaged, or torso, however bruised, is rendered with the reverence we might more readily associate with classical beauty. Critic Matt Price has already noted that “Mortimer’s paintings are not without precedent.” He inserts them into a long line of war and military-inspired works from the paintings of Uccello down to David, Delacroix and Gros. Like David before him, Mortimer is an adept handler of flesh; indeed the female nude and the small child often find their way into his desolate landscapes — fragments of beauty amid the chaos of war.

In addition to his delicate and respectful treatment of the human form, Mortimer’s personal history has found its way into his work. As a boy the artist was fascinated by military models, spending hours making diminutive airplanes, even creating complete scenes featuring occupied houses with miniature furniture, light fittings and sand bags. Perhaps this fascination for all things military occurred because his father was a naval helicopter pilot and the young Mortimer would hear stories of the campaigns he was involved with. But this interest doesn’t account for the artist’s fascination for the human form — most especially the leg and lower limb. Mortimer himself acknowledges that there is often a “high concentration of legs” in his paintings. Clearly this is no accident; it’s a motif the artist returns to again and again. In Community Project (2009) we see the back end of an open truck. Mortimer is careful not to give us the whole story — he plays with us, giving us just enough information to create our own interpretation of events, drawing us in and prompting our imaginations to do the rest. Bodies are piled high, but all we can see are legs twisting together and stacked in such a way it seems they are about to fall out.

Garden (2009-2010.) Courtesy the Artist and Master Piper, London. Photography by Anna Arca.

Mortimer himself was born with a twisted tibia that resulted in him having to endure endless operations and hospital visits as a child and young adult. He remembers feeling very scared of large hospital-related machinery such as the x-ray machine. The surgical dress code and stylized hospital materials paraded themselves through his nightmares — lab coats and doctors’ scrubs, masks, signs pointing to “hazardous waste” and dustbins and bags overflowing with human detritus. In the young child’s mind, we could well imagine that the war imagery and the intimidating machinery of the hospital could well become fused together. Perhaps Mortimer’s personal experience and childhood games continue to play a part in his work. Though Cleaners (2009) references the kind of suits worn by professionals after a chemical spillage, it is possible to map a strange course from the surgical scrubs to the mountain hikers, conspicuous by their absence from Mortimer’s alpine scenes. All is strange, all is surreal and yet all somehow fits.

Žižek argues that we all “imitate peace, live in a fiction of peace… this alleged normality is itself an island of fictions.” Mortimer’s works bring this home: in one strange way or another we’re all at war — there is no ‘them,’ only ‘us.’