Every year when I teach my art history class deconstructing the Western tradition of modernism I start with Romanticism, anchoring the movement in the colonial context from which it emerged. Orientalism and fantasies of the noble savage are explored to embody these connections, and the quote I often use to explain the latter is by George Catlin: “We travel to see the perishable and the perishing,” he wrote in his journal in the 1830s. “To see them before they fall.” It never ceases to shock me that Catlin, whose Wikipedia page still describes him first and foremost as an “American adventurer specializing in portraits of Native Americans in the Old West,” could have no awareness of the rapacious nature of his observations. But then all one has to do is consider the world he lived in, the carte blanche pass he had as a white man who could treat his archival project of documenting the remaining indigenous communities he encountered as one of righteous salvage.

The Palestinian-born artist and filmmaker Jumana Manna’s explorations into land rights, plant taxonomies, and the ongoing struggles for sovereignty in the Middle East implicate this same colonial mindset in the twenty- first century. Throughout her work, she reveals the consequences of an archival impulse to procure and control not just nature, but culture and knowledge as well. Speaking of her film Wild Relatives (2018), for example, which considers the power dynamics of centralized seed banks and industrial agriculture, Manna reminds us that Catlin’s disturbing sentiment is still very much with us: “They are another manifestation of this classical modernist contradiction of the urge to preserve the very thing being erased, and this has been a red thread in much of my work.”

Manna’s film entwines the stories of two seed banks in particular. The first is the International Center for Agriculture Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), which originated in Lebanon, moved to Syria during the Lebanese Civil War in 1976, and remained there until that country’s 2021 revolution required it be moved again. The goal was to return the seed bank back to Lebanon, but the seeds never made it. So in 2015, for the first time since its inception in 2008, the Global Seed Vault in Norway — the second seed bank in Manna’s film, and the world’s largest repository of wild and domestic seed varieties — issued a series of duplicates.

In a particularly telling scene in Wild Relatives, Manna attends the press conference for this historic event in Svalbard, Norway, the arctic coal-mining island that houses the seed bank deep inside the bowels of a mountain. There we hear its Norwegian representative subtly admonish ICARDA’s delegates, stating: “Ideally, we have this [vault] as a security deposit for the world and we hope, to be frank, that it never needs to be used again. Because if things work around the world as they should, then we shouldn’t need to take seeds out. But because of the situation in Aleppo, as we all know, it needed to be done.” No mention of the devastating destruction of Syria — a geopolitical pawn among imperial powers vying for its energy resources — or the fact that the Global South has for millennia generated the bulk of seeds that now reside in the Global Seed Vault. Instead we are shown the superiority of a Western nation invested in its image of neutrality, which, like the seedbank itself, is ultimately a myth. It is Syrian refugees — nearly all women — living in Lebanon who become the real heroes of Manna’s film as we watch them painstakingly reconstruct ICARDA’s former collection of 40,000 regional seeds in the fertile Bekaa Valley. In moving, poetic scenes that foreground the beauty of the verdant rolling hills in which they work, Manna imbues her essay film with a bucolic beauty that does not hide the contemporary political conditions that shape her subject’s existence and labor.

Wild Relatives emerged out of an earlier research-based project, Post-Herbarium (2016), which connects the art of botanical illustration and still life to the history of colonialism via the Lebanese herbarium established by the nineteenth-century botanist George E. Post. The American missionary, who gathered thousands of specimens from Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt, is credited with being the first to write about the flora of the region in English. Post-Herbarium features intricate landscape and floral still life collages made from the cut-up packaging of cleaning products, conveying not only the impact of consumer culture on the environment but Western attitudes toward the “dirty” Global South. Other elements — empty bleach bottles, large plywood cutouts of regional plants, sculptures resembling storage systems, and a mise-en-scène of the missionary’s desk — suggest extricable links between Post’s religious agenda, the rise of settler-colonial Zionism, and the archive’s formation. Other elements — empty bleach bottles, large plywood cutouts of regional plants, sculptures resembling storage systems, and a mise-en-scène of the missionary’s desk — suggest extricable links between Post’s religious agenda, the rise of settler-colonial Zionism, and the archive’s formation.

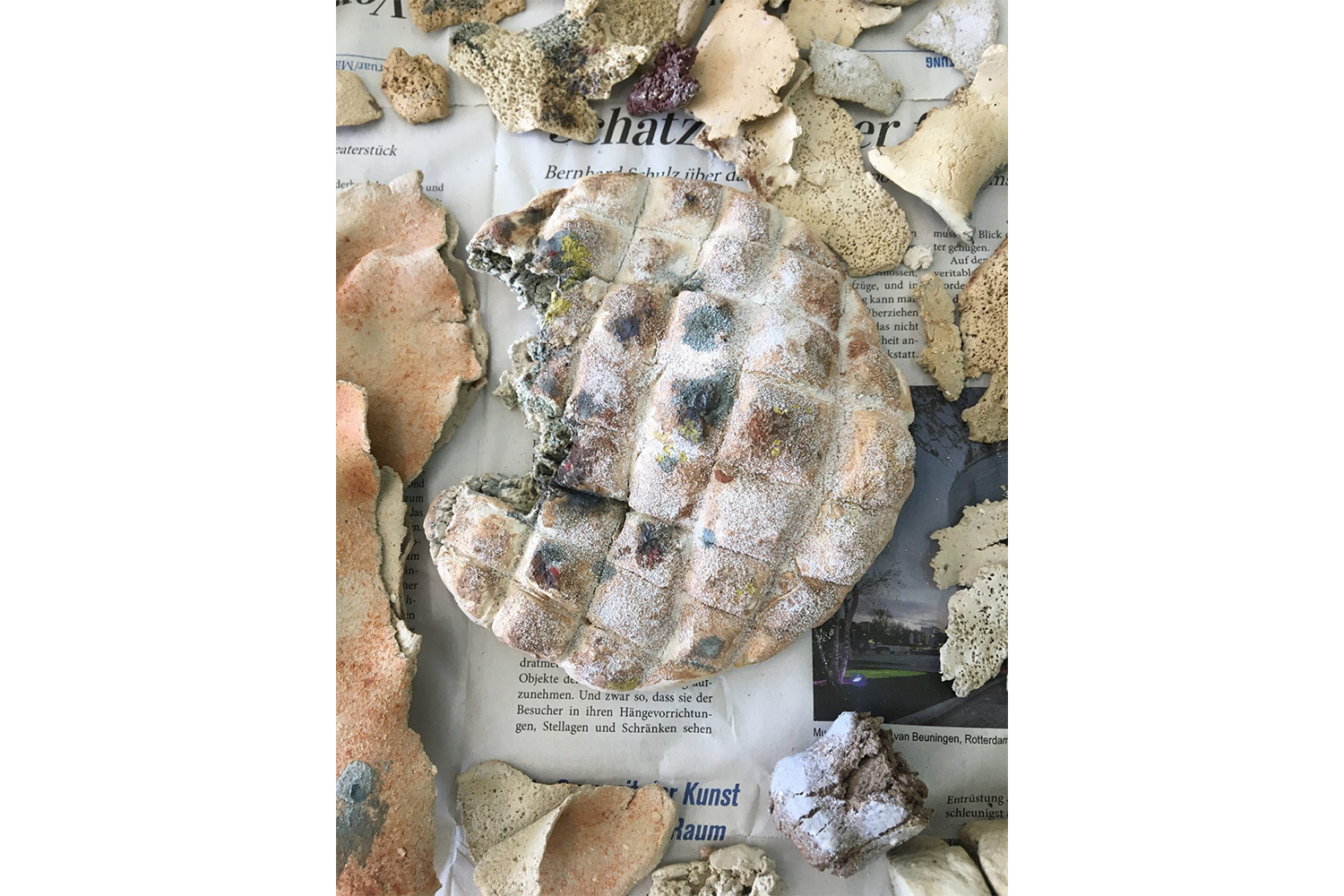

Manna’s “Cache Series” (2018–ongoing), an abstract series of ceramic sculptures, likewise engages the history of grain storage systems to invoke the politics of extinction as a cultural and ecological term. The series underscores the loss of sustenance-based agricultural traditions in the face of industrialized systems of farming designed for accumulation and profit. In her current solo exhibition at MoMA PS1, “Break, Take, Erase, Tally” (2022), these clay vessels take center stage, reproducing the rural khabya containers used for millennia throughout the Levant. Some faithfully recreate the small structures while others render them in various states of ruin to convey their forlorn, now obsolete status. The chambers are laid out for viewers like ethnographic specimens atop the kind of modern steel grates used in climate- controlled storage systems for agriculture and museums alike.

Ranging from flat interlocking geometric squares to standing biomorphic forms, they are depicted in a variety of colors — terra-cotta, egg-shell white, mint green, and chocolate brown — that evoke the land to which they belong, their soft edges and lime-plaster surfaces echoing these associations. The sprawling architectonic forms also allude to the abandoned and destroyed villages from which they come that have been long displaced by war and urbanization. Like the ceramic slag and broken pottery that surrounds them, they are mournful specters of self-determination and sustainability.

In what is perhaps Manna’s most personal work to date, the film Foragers (2022) takes up this theme of self-determination to yet again underscore the power relations and contradictions inherent to colonial concepts of preservation. Foragers is both a celebration of culinary traditions in her native Palestine and a critical examination of recent Israeli laws prohibiting the age-old practice of scavenging wild edibles. The hybrid fiction-documentary stars actors and non-actors alike, and grew out of Manna’s quarantine experiences during COVID when she returned home to live with her parents in Shu’fat, Jerusalem. At the heart of the film is the government crackdown on the gathering of akkoub, a cross between an artichoke and asparagus, and za’atar, an herb in the mint family. Collected for centuries by Palestinians, these plants are now being legally protected based on dubious claims that they are endangered.

The absurdity of the fervor with which Israel’s so-called green patrol hunts down those who dare to pick them on expropriated land that historically belongs to them drives the tragicomic tone of the film. Domestic scenes of elder women laboriously pruning akkoub — a prickly plant — in their kitchen are juxtaposed with re-staged court hearings where those accused of breaking the law are forced to defend themselves. That a people whose very existence is daily threatened by Zionist expansion is held to account for practicing ancient foraging traditions on their own land is not only ironic, but a strategic means of furthering Israeli claims to that land. Writing about the work in an e-flux article, Manna sums it up as such: “Over the past seventy years Palestinians themselves have been treated as an invasive species in urgent need of elimination and control. The protection of one form of life — nonhuman life — has been used as an extra tool to suffocate a people who have survived attempts at cultural erasure and ethnic cleansing.”

Manna’s ability to tease out the Zionist enterprise as a giant restoration act in and of itself is a powerful lesson — that the appropriation of nature in the name of science and environmentalism often masks colonialist agendas. Like Catlin’s messianic project nearly two centuries earlier, the notion of preservation as a moral act of rescue continues to paradoxically threaten indigenous people worldwide, whose struggle to maintain their rights to stolen lands cannot be separated from their very survival. Manna’s work asks us not to forget this, and warns that if we do we are all doomed.