Just days before the US election, as Americans were grappling with the fallout of a global pandemic, a summer of protests targeting police brutality, and collective anxiety around the future of the nation, I sat down with acclaimed artist Julie Mehretu. We met at Marian Goodman Gallery, where the artist’s most recent exhibition of new work, “about the space of half an hour,” intimated an elephant in the room that neither of us could escape; the show’s title and the eponymous suite of paintings made in 2020 nod to the end of times. According to Mehretu, the title “speaks to the uncertainty of our current moment and the precarity of our future.” This feeling of uncertainty is echoed, if not foreshadowed, in the scripture of Revelation 8:1, in the moments of silence in heaven after the seventh and final seal of rapture has been unleashed on the world. “None of us knows what’s going to happen.”

Mehretu’s awareness of these struggles is what motivated her to continue working through the most challenging moments of 2020. “This is precisely the time when artists go to work,” she says, quoting Toni Morrison with admiration.

In the show, Mehretu dedicates an entire canvas to Morrison’s novel A Mercy — a striking narrative about enslavement and generational trauma told through the life of a young girl named Florens. The work is a beautiful example of the artist’s signature style of mark-making emblazoned in a flurry of gold and garnet, inspired by the work of the late writer whose texts and critical approach Mehretu revisits often. “For me, I felt so grateful that I had this practice to go to, this place to go to during the shutdown; this refuge, at Dennison Hill, a place in the country where my family could go to quarantine and where I could get lost in work,” Mehretu shared. The farm and creative haven in the southern Catskills became a non-profit in 2004, but Mehretu’s involvement in the creative community began in 2001. “I made my first solo show in the city up there and then this group of paintings,” Mehretu recalls. “I felt so grateful to have a way to metabolize this time.” And what a time it has been. The pandemic and a heightened awareness of racial bias in the United States have exacerbated and magnified the extent to which the institutions of capitalism and white supremacy have divided Americans along race and class lines.

“As we move through this time of precarity, and [consider] the catapulting manner in which neo-capitalism has pushed us further and further away from any kind of possible democratic future, you move into this place where you have to invent some other ways. That is the driving force of Denniston Hill.”

To examine the development of Mehretu’s style and technique from 2001 to 2020 is to be cognizant of varied shifts in scale, opacity, and color. The recent works highlight the feeling of universal smallness one feels in the presence of Mehretu’s monumental abstractions, albeit on a much more intimate scale. Faced with the COVID-19 shutdown, the artist, like many others around the world, was forced to reimagine her practice, though this limitation seems to have opened the door to new experiments with her familiar mode of abstraction. “These paintings came quickly, but I had like six months of uninterrupted time with them,” Mehretu admits. For an artist who engages in countless interviews, travel, and programming around exhibitions, and who usually spends summers in Berlin, a span of six months of uninterrupted time does not come around often. Creating in a space where days and weeks don’t necessarily mark the same passage of time as they once did but are instead reminders of the collapse of that time, allowed Mehretu to think critically about time, space, and the forms that inhabit her paintings. The artist urges, however, that “time has always been important in my work, from the layering of all this architectural language, and this aspect of — or the capability of — collapsing time in that.

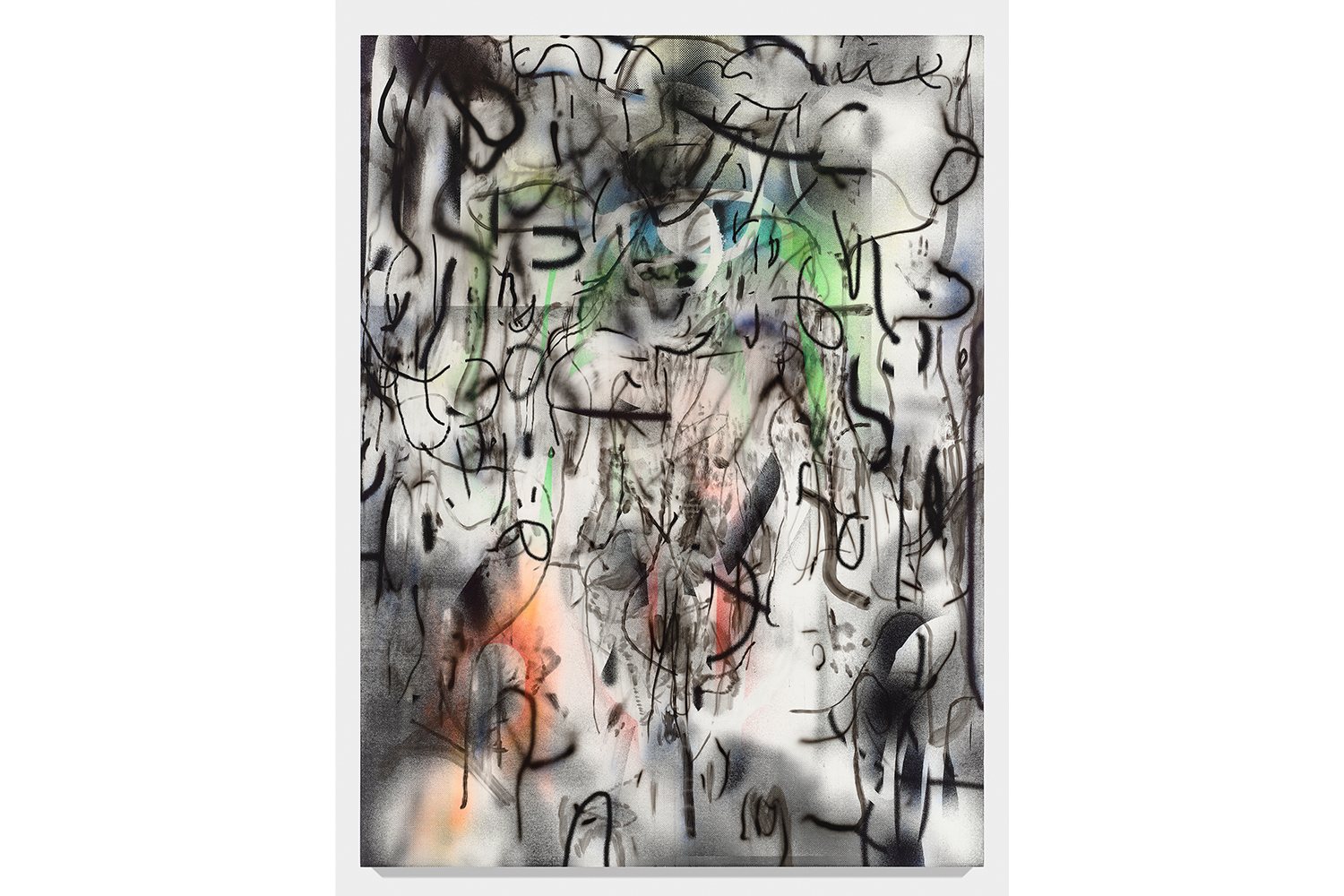

I think even in front of Conversion (S. M. del Popolo/after C.) (2019–20) or A Mercy (after T. Morrison) (2019–20) in the other room, there’s this aspect that reaches back almost to the Renaissance in a way, and then kind of catapults forward.” Perhaps, more than ever before, Mehretu steps out from behind the veil of complexity to embrace an approach to abstraction that is increasingly fluid. The intricate layering of architectural plans and cartographic renderings has all but disappeared, allowing a visible tension between the figurative and the abstract, between line and color, to emerge. There’s a tenuous relationship that can be detected in some of the works in which Mehretu painstakingly labors to construct an image or an abstraction, and at other times deliberately erases and obfuscates forms. “That whole thing becomes experiential where there isn’t necessarily language at hand for this visual experience. It becomes this time-based experiential dynamic. It’s a visceral experience.”

Like many artists before her, abstraction has been the hallmark of Mehretu’s practice since she began painting and, despite the current resurgence in figurative painting among Black artists, Mehretu has remained dedicated to the practice, though not at all limited by it.

The long history of Black artists working in abstraction, both artistically and musically, has been a primary influence on the artist’s technique, as well as a radical foundation for the language she uses to conceptualize her own practice. One explicit historical reference, which appeared across the body of works in “about the space of half an hour,” is to the work of David Hammons’s body prints composed in the 1970s. In Mehretu’s first suite of paintings, the allusion to the physical human form appears most prominently, but also extends throughout the work in the form of stray handprints and fingerprints, which starkly contrast Mehretu’s use of airbrush finishes. She explains, however, that the work also references other great abstractionists, such as Jack Whitten and “the cosmologies, fractions of light, spaces of liberation, and other ways of thinking through this experience that we have. You can go back to Coltrane — there’s so much rich history in mining abstraction for liberation,” the artist assures. “In fact, most of the newer paintings that are in the LACMA survey each have a shout out to an important piece of abstract music from the Black radical tradition and, in that, point to a place of imagination and desire that insists on something else .It maintains itself and it continues to invent itself despite every effort to extinguish it.”

Through her practice, Mehretu celebrates and makes space for the Black radical tradition in the art world, though Mehretu doubts that Black feminist thought and critical race theory are going to save the art world from its race and class problems.

“I would be skeptical [ about thinking that we are moving towards that [way of thinking] because I really feel like what we’ve witnessed and we’ve experienced as a culture in the past, is a constant co-option of efforts when there is some kind of shift,” she argues. “And the filling of that space with a reactionary reclaiming of aesthetics. We’ve seen it from the early ’90s, after we saw this kind of really amazing identity political work that came to the fore. You know, the 1993 Whitney Biennial, the “Black Male” show… all this stuff. And then you saw the denial and co-option of that in the mid-1990s by the desire to go back to beauty — The Return of the Real (1995) by Hal Foster, Air Guitar (1997) by Dave Hickey — and like what happened with that? It was this way to evaporate identity politics from aesthetics. It also happened in the late 60’s and early 70’s after the civil rights movement. And critically, I think you see that delineated in the history of Black abstractionists and how, where, and in what space their work could exist. In terms of white criticism, there was the denial of the right to abstraction.”

In this context, the Édouard Glissant quote that Mehretu uses to introduce the works in the show is presented with greater clarity. In his essay titled “For Opacity,” the Martiniquan writer, poet, and critic declares, “We clamor for the right to opacity for everyone.” In Mehretu’s case this opacity can be interpreted both formally and figuratively. “I think amongst the writers of créolité — Glissant, Fanon, etc. — there was this really radical way of thinking about themselves, as unique to their experience in the Caribbean. The continual colonial project experienced in places like Martinique, Guadeloupe… What’s so interesting about what happened in that context was the insistence on Créolité, the hybridity of self, this constant negotiation between the colonial self and the [experienced self], similar but unique from what Dubois expressed with double consciousness. Here: the complexity lay in that one wanted to create within that, rather than acquiesce to the kind of forced descriptive/explanatory model that is expected here in the United States. I’m not saying that artists did that. Most people actually tried to articulate themselves in very complex ways, whether through literature like Baldwin or Morrison, or in the decades of abstraction that we’ve seen. There was this effort to relocate what a narrative is and who one is in that, and that is super crucial.”

“What I loved about that quote is that I had been insistent on abstraction since I started to work, and I found it to be this liberating space. So the right to opacity can also be the right to abstraction. I remember, I even had a critic ask me one time. ‘Well what does this mark mean?’ He literally went through the piece and asked about every mark.” My question to Julie in response was rhetorical: “Who does that serve?” “Exactly,” Mehretu responded. “But that’s what is expected of Black artists; this articulation of who you are, like defending yourself. And I think it comes up in that quote, to go back to Morrison, when she says,

‘The very serious function of racism is distraction.’

Because if you are constantly having to define yourself and constantly having to prove yourself as part of a constant exhausting negotiation with racism, it’s undermining, and that is very destructive to creative process and invention and space. I think you have that [in jazz]. Jazz became this form for that space of abstraction and liberation, it was invented as a form for that space, but I think in visual arts we’ve had a different sense of hegemony for so long that it didn’t allow the inclusion of particular practices — and I want to specify — from particular practitioners.” For Mehretu, opacity is a space of liberation.

“Within opacity and within the creative space of how do you invent something else? begs the question, Who are you? and How can you be something culturally other than this flattened caricature? That’s the goal. There’s no transparency to who we are as individuals and our lived experience; its fully opaque and I love that.”

Considering Mehretu’s desire for opacity, she is very willing to discuss her process, so long as it is on her terms. The artist’s work has become highly technological in its use of media imagery and the layering of forms via paint, ink, and other processes.

“Making work, it’s always like one small step leads to another, and usually there are the kind of mistakes or happenings, surprises or other things, that happen by chance in the studio.

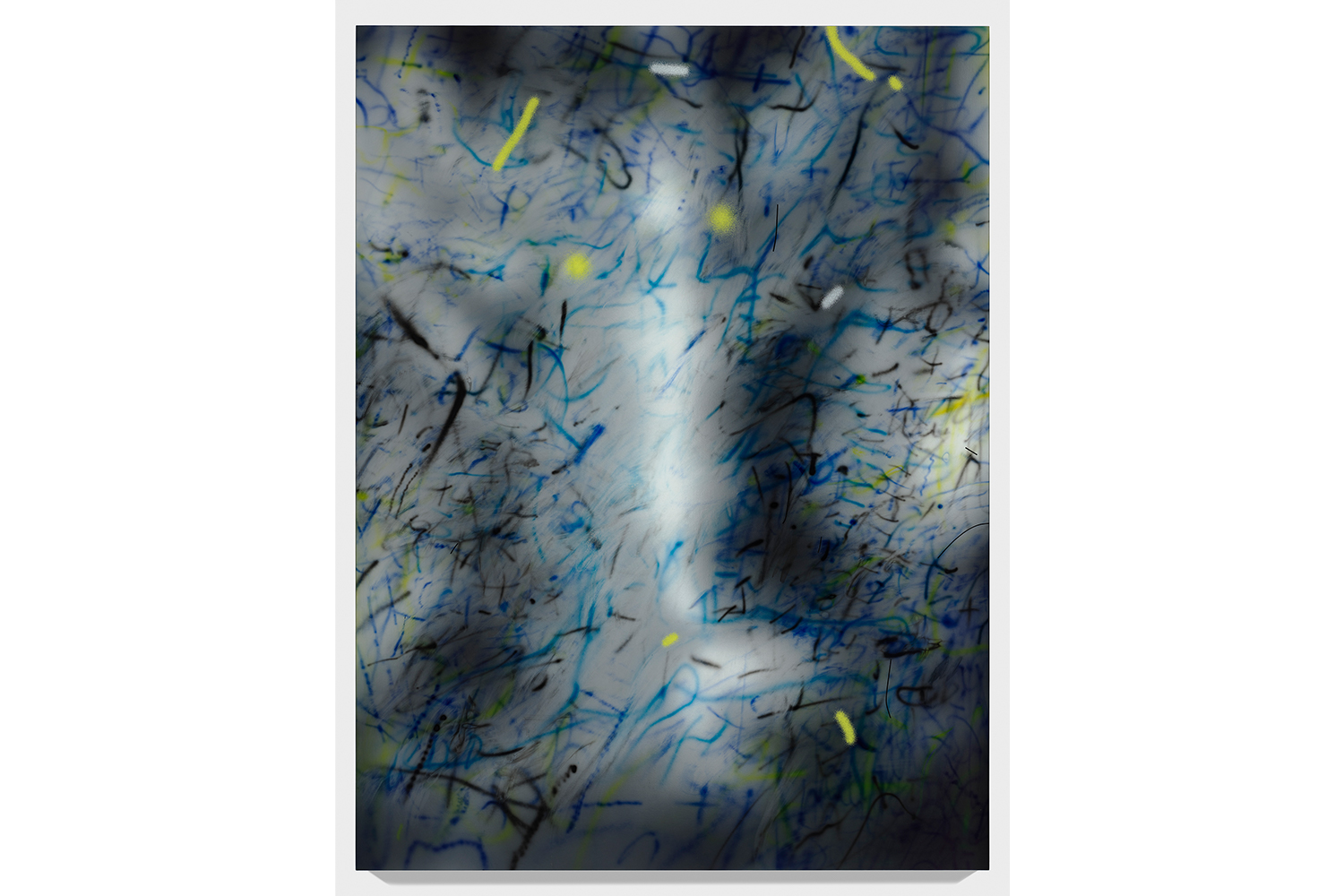

A serendipitous thing leads to a whole new thing.” This is how Mehretu explains the process by which she began using mass-media photography as a base for her paintings. “One time I was projecting and tracing these buildings onto the canvas from news media photographs. I was tracing this image of this bunker in Iraq, Saddam Hussein’s palace where all these press conferences took place, and which the Americans bombed to smithereens. At one point when I was projecting it, the projector was blurred and you saw this blurred image on the page. And, I don’t know, something was so profound to me, and so potent, in that image. It felt like everything I was trying to do with this architectural drawing just emerged in this blur. It felt like the specters of that image, the light and the forms, allowed for this other kind of dynamic to exist in the image. So, then I actually decided to start playing with that in Photoshop… I really wanted it to look like this kind of haze of a blur where you can’t see the image yet the form and suggestion of color and light are still apparent. It also kind of reminded me of [twentieth-century] experimental photography where photographers tried to play with the mystical and attempted to photograph the spirit, the ghosts around us, and a lot of it ended up being just optical shit that would happen with lenses but they would catch the illusion. The blurred photographs reminded me of that effort, as if you could catch something else with that photograph if you looked at it blurred. It also gave you the light, line, and space without the definition of the actual image, and I was super interested in that. Like, how do we intuitively respond to these things?”

The way images are presented to us today, however, has significantly changed how we interpret photography. “I think that what the media does to photographs — and I’ve been working with this archive of media images for twenty-five years, constantly pulling from the world around me — what we’re experiencing now is a deluge of that.

We consume images more than we consume food. It is the fundamental staple to how we understand ourselves and our time, who we are, and where we are.

And for each person, that can be a radically different reality. But still, there is this kind of constant, weird, intuitively connected place where we are, where we understand certain events, certain times. There are specific images that always rise to the top, that become definitive. You can think of 9/11 and you know what those images are. You can think of Charlottesville and you know what those are. They become recurrent. Those are the kind of images that would haunt me, I would find for myself, and those are the kind of images that, when you look back, become the stand-ins for that moment in time.” Mehretu has employed media images of protests in Charlottesville, California forest fires, and destruction caused by Hurricane Irma for the works in “about the space of half an hour.” In her survey show, the artist deconstructs other troubling spaces and events that persist in the public consciousness through the circulation of images.

“I study so much painting,” reveals the artist, “but it’s definitely a conversation across time and space.

So, I do think [time] is really a potent thing. And I think especially right now, because of all the conditions that we are talking about, the ideation of the twentieth century as a time of progress, and these kinds of possibilities of a progressing future, that if that is falling in on itself, we can only live in the moment.”

Our current moment, because of its difficulty and its disruption, awakened many to be critical of the illusion of progress. Even as organizers rallied the vote last fall in hopes that frustrated Americans would vote Donald Trump out of office, many expressed that the events of 2020 had exposed too much of the tattered fabric of the country for one politician to repair. It has been less than three weeks since the inauguration of President Joe Biden, and discontent is already brewing from citizens on the right and the left. These recent works are deposits of Mehretu’s practice as it continues to metamorphose — capturing the world around us as it changes and cycles back through repeated and unresolved histories, like a mirror through which chaos is refracted on the canvas. But Mehretu’s practice is also a reminder that the solution is not simple, and it is not necessarily hidden in our past or awaiting us in the future.

“It’s not just about survival, but in a way it is. You can look back on the past and make sense of things, but when you are in this moment of precariousness, or in war time, or whatever, there’s this kind of disintegration of a kind of expected future or a determined future.”

The present may be all we have, but Mehretu does not want her sentiment to be interpreted as blind pessimism.

“On the verge of extinction is invention,” says Mehretu, and she recommends a book titled The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruin by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing. The book centers on the anthropologist’s research into the history of the matsutake mushroom, a Japanese delicacy that grows mainly in barren landscapes destroyed by deforestation and other forms of environmental destruction. Summarizing the book, Mehretu explains, “It’s not because [the author] thinks that the ‘answer’ lies in the story of this mushroom, but that the story of this mushroom allows our imagination to think differently about how to live this precarious future. How do we make sense of it? And because this [mushroom] is a thing that actually lives off of deforestation, in that space of the abyss, if you will, how can you imagine a future in that space, since that is where we are.”