“After Images” at Julia Stoschek Foundation in Berlin is an exhibition without images — or almost. Most of the more than thirty works fit the “time-based” focus of the foundation’s collection, which emphasizes film and video. But since most of the pieces in the collection include images, the exhibition primarily consists of loans and new commissions.

The curation unfolds along the space of the foundation, which is housed in a former Czech cultural center — a sober, modernist structure on a street corner in Berlin’s former East. The large windows are curtained with stiff, pleated fabric, which gives the space an almost liturgical appeal. For this show, the rough spaces alternate between museum-like rooms and darker, immersive ones.

The first room falls into the former category. Here Trisha Donnelly’s untitled slab of rose marble (2023) lies on the floor. Donnelly requests that there be no documentation of her work — no images — but the foundation playfully counters this by pairing it with Ghislaine Leung’s Monitors(2022), a camera connected to a baby monitor on another floor. No image is recorded, but the device ensures a fleeting image, changing the monitor’s usual purpose.

Donnelly’s works, which run through the exhibition like a red thread, include a sound piece and an almost painterly video work that is painfully slow to watch. Just when you least expect it, the abstract piece bursts into activity. It is paired with a richly layered composition for piano, violin, and cello by the musician Laurel Halo, who, for the first time, created a piece for an art space.

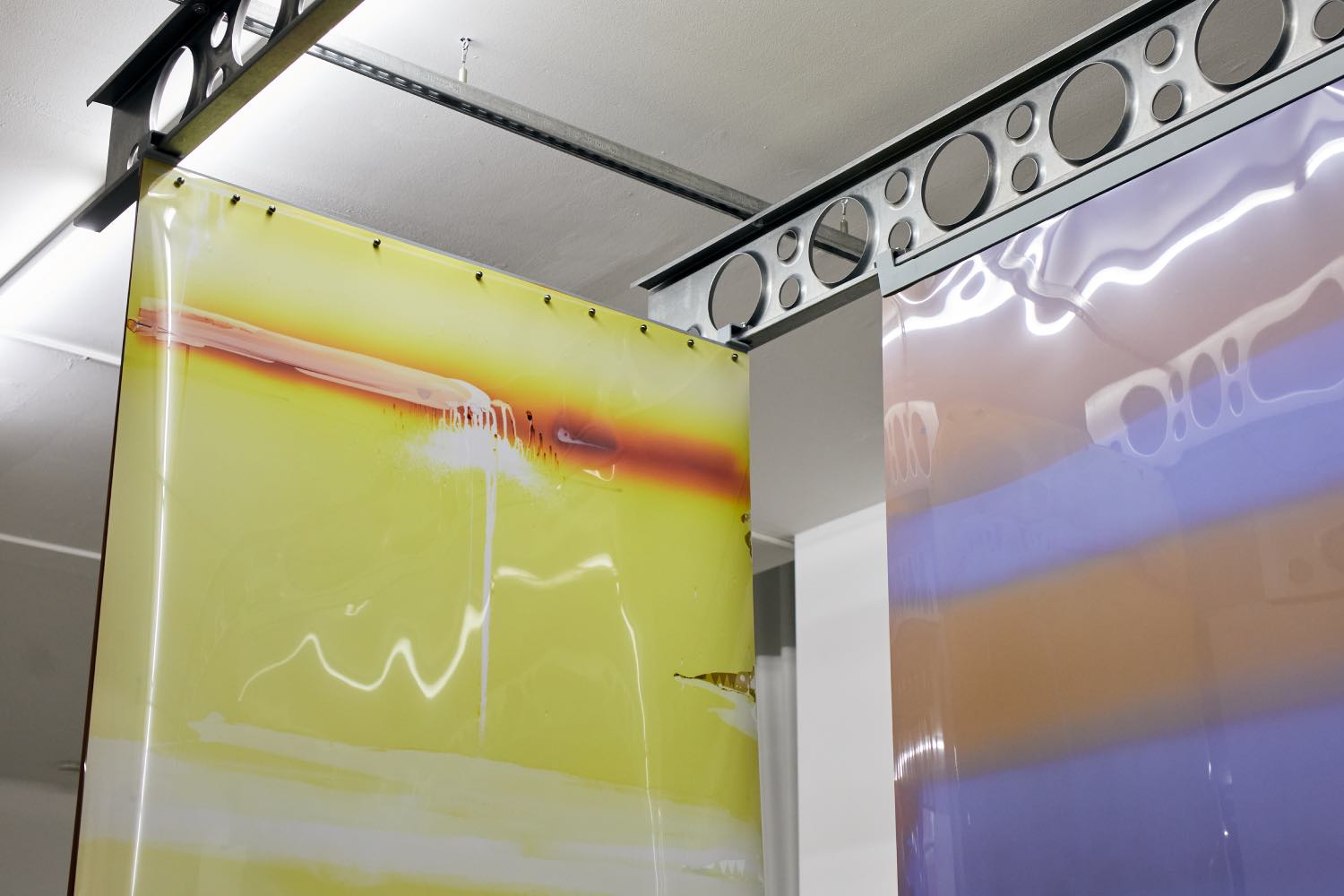

Movement through space is a key concept in the exhibition, recalling Sergei Eisenstein’s essay on montage and architecture from the 1930s. For Eisenstein, architecture, animated by bodily movement and time, serves as a precursor to film. Perhaps Lotus L. Kang’s installation Cascades (2023) echoes this interplay. The artist’s large-format, light-sensitive celluloid strips are suspended from the ceiling, and they have been exposed in a greenhouse in New York, resulting in earthy hues of purple and burnt orange. The pieces, which Kang calls skins — and indeed they resemble organic hides — are not fixed, and thus will, imperceptibly, change over time. Kang juxtaposes them with tatami mats, in which she hides photos and small bronze sculptures. The installation is full of images, albeit invisible ones.

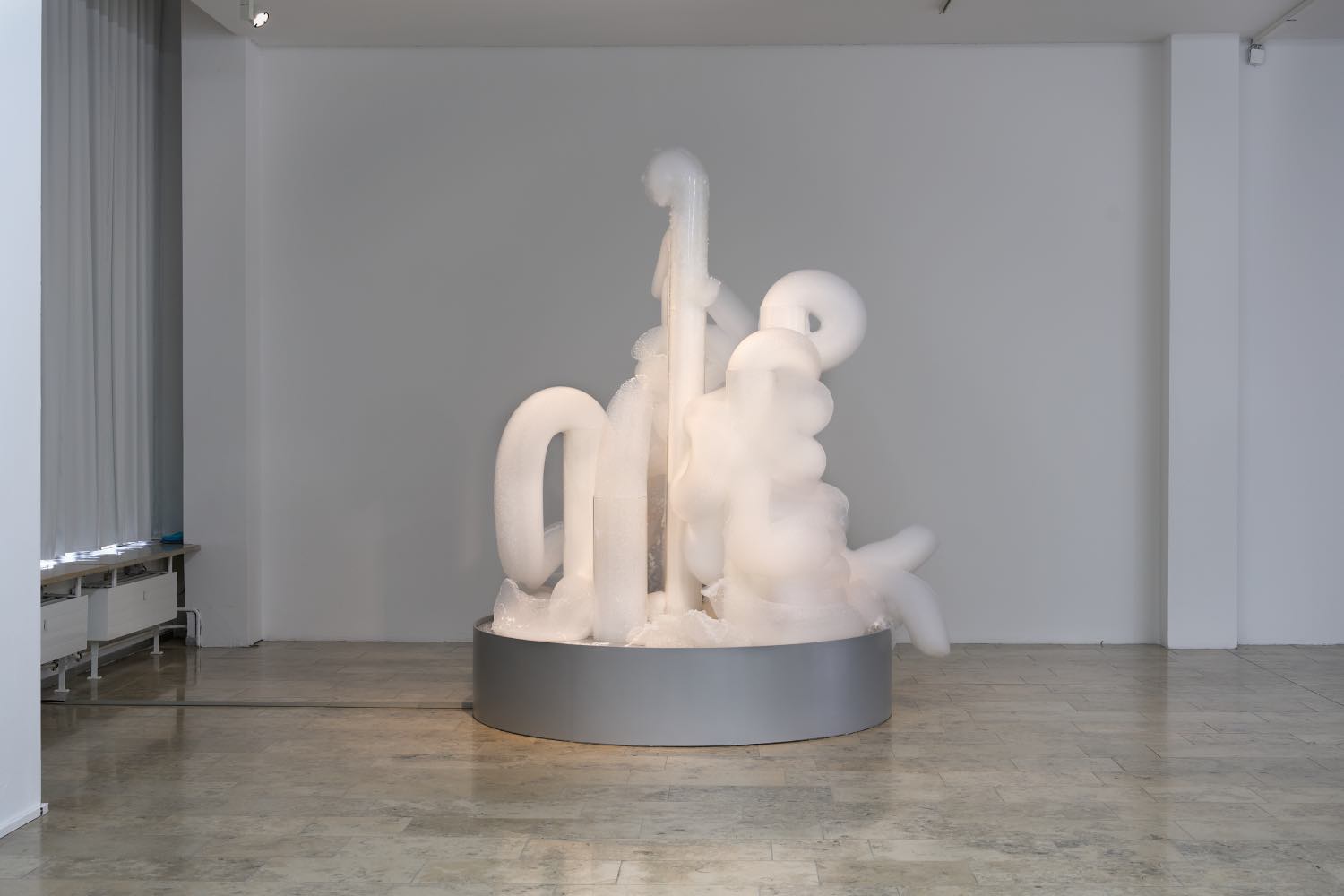

The shift from brightly lit rooms to darker, immersive ones resembles a kind of contrapuntal montage, addresses senses other than the visual. One room is bathed in turquoise light, and on the floor Chaveli Sifre placed four glass sculptures in the shape of four limbs, filled with camphor, a fragrant substance that passes directly from solid to gaseous at room temperature. David Medalla’s slow-moving foam sculpture Cloud Canyons (1963/2018) invites touch. Then, like a hyperactive descendent of Medalla’s languidly meditational piece, Paul Chan’s colorful, anthropomorphic pieces from the ongoing series “Breathers” (both from 2024) wave zanily, like video works without a screen. Rosa Barba’s installation One Way Out (2009), which uses projectors and empty film strips that get progressively scratched, suggests a self-consuming medium. At times, the exhibition aims to reduce screen time, often avoiding images in the traditional sense in order to explore other media. By doing so, it reflects on the ways contemporary art creates images obliquely.

The show’s title has at least two meanings. The phrase “after images” suggests a state beyond images, or, like “postmodern” or “post-internet,” hints at the persistence of something thought to be passé. However, to me, the show critiques the hierarchy of the senses, with vision at the top as the sense that is most discerning and closest to reason. Touch, hearing, and smell (taste is absent from the exhibition) might prime us for rethinking how we interact with the world; and somewhat hidden in that shifted focus is a critique of enlightenment reason, which, at the outset of modernity placed vision above the other senses. The title “After Images” can also be read as a paraphrase of the unrepresentable. However, much discourse around the inadequacy of images in past decades has been linked to the depiction — or its absence — of violence, war crimes, and genocide. Although this exhibition is not about the failure of visual representation, it is notable how few works deal with violence.

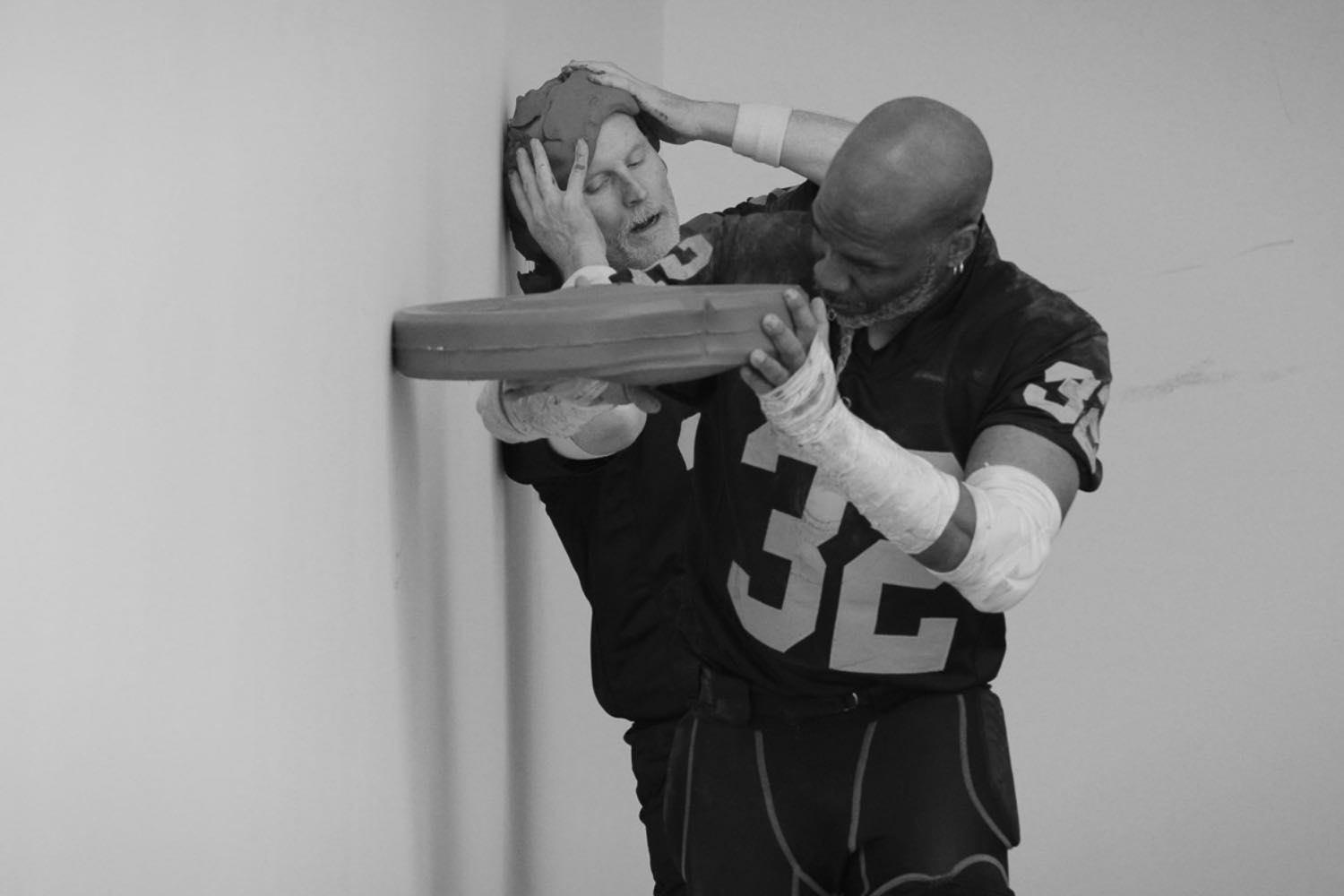

That is not to say it’s absent. In the large cinema upstairs, “After Images” culminates in the operatic, multi-sensorial installation Silence (2024) by LABOUR, a collaboration between Farahnaz Hatam and Colin Hacklander. The piece references Zoroastrian sky burials, and the composition is inspired by Iannis Xenakis, who likewise worked with the distribution of sound in space; at the center is a claw-like sculpture that looks like it should topple at any point (it is held upright by strings), which is a three-dimensional rendition of Xenakis’s handwritten notation. Strobing lights and cascading sound make for a cathartically abrasive sensory experience. At the end there is silence.

That is not to say it’s absent. In the large cinema upstairs, “After Images” culminates in the operatic, multi-sensorial installation Silence (2024) by LABOUR, a collaboration between Farahnaz Hatam and Colin Hacklander. The piece references Zoroastrian sky burials, and the composition is inspired by Iannis Xenakis, who likewise worked with the distribution of sound in space; at the center is a claw-like sculpture that looks like it should topple at any point (it is held upright by strings), which is a three-dimensional rendition of Xenakis’s handwritten notation. Strobing lights and cascading sound make for a cathartically abrasive sensory experience. At the end there is silence.