During the making of her exhibition “Moving Off the Land II,” currently on view at Ocean Space in Venice, Joan Jonas maintained an ongoing dialogue with the marine biologist and ocean explorer David Gruber. Jonas’s experiments with video and performance in the late 1960s and early 1970s continue to influence artists working today, and animals and the “natural” world have been recurring touchstones in her multifaceted practice. On the occasion of her show at Ocean Space, she focused on underwater ecologies and the manifold creatures inhabiting them. Below, Jonas and Gruber respectively describe the way their dialogue unfolded over the past year and a half; how during this process they delved into the topic of communication between marine mammals and the impact of sound pollution; and what we can learn from nonhuman linguistic patterns.

Joan Jonas

Nature has always played an important part in my work. In recent years, the environmental situation has become more and more important to me and visible in my work, due to the increasing threats to our livelihoods and that of numerous other species. I based the installation and performance Reanimation (2013) on the novel Under the Glacier (1968) by the Icelandic writer Halldór Laxness. It is a fantastical dark tale set in the western part of rural Iceland. Since the subject involved the magical beauty of a particular glacier, I had to consider the fact that glaciers are now melting. Laxness wrote poetically about bees, birds, and fish. And so his descriptions of the miraculous everyday survival of these creatures, as well as their dances, became part of the work as well.

I have continued to explore environmental concerns while focusing on these creatures that inhabit our world in the piece I did for the US pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2015, titled They Come to Us without a Word. In 2016, Ute Meta Bauer, who curated the pavilion, invited me to do a performance in Kochi, India, during a convening she organized with Stefanie Hessler for the TBA21–Academy. I felt that it would be important to become involved with a group of people who were addressing serious questions concerning the ocean and its survival. The videos and drawings in what I have come to refer to as the “fish room” — a room in the Venice pavilion — was a starting point.

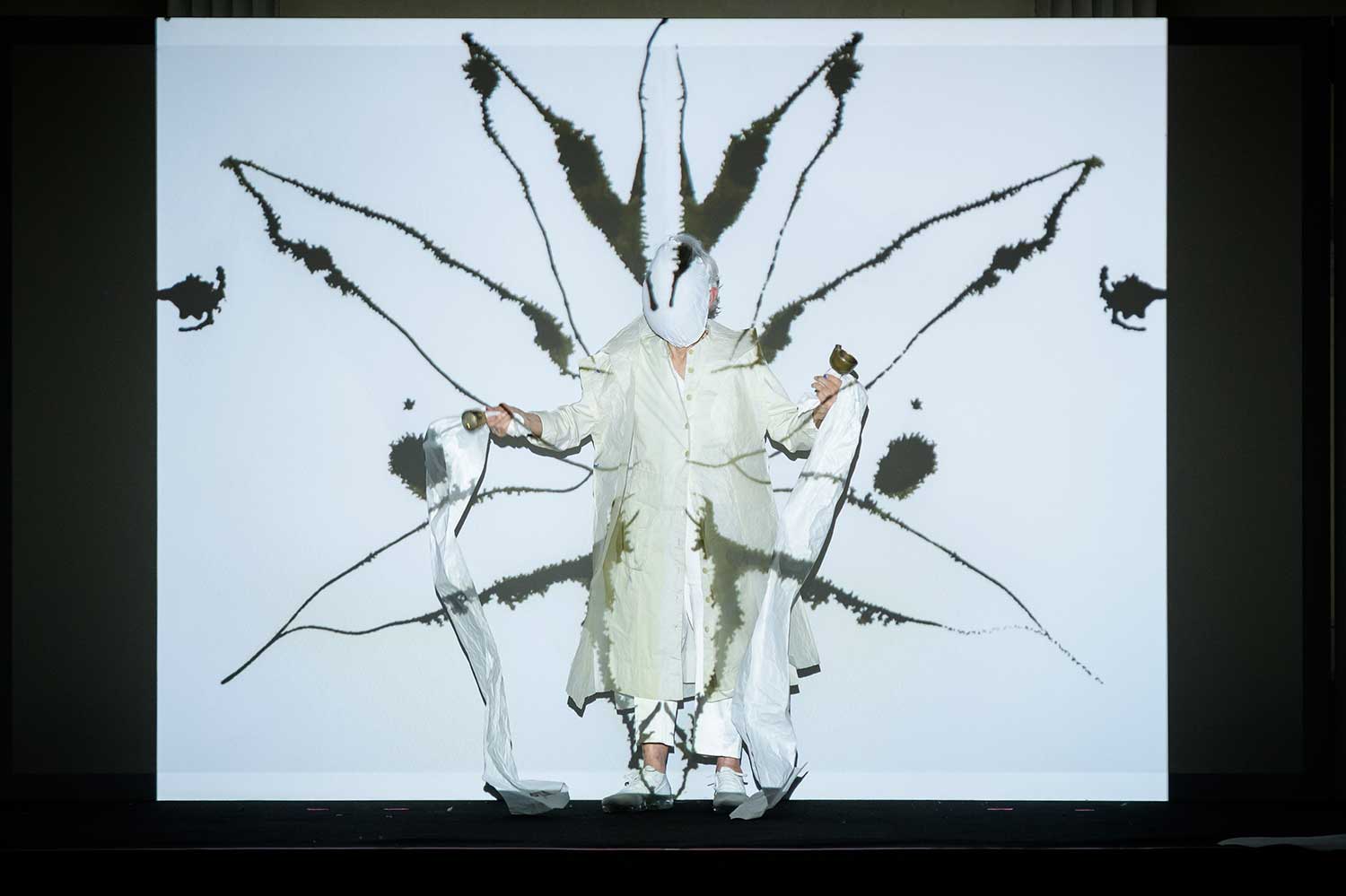

The first version of the performance Moving Off the Land was presented on a small outdoor stage on the Vasco da Gama Square in the old town of Fort Kochi as a lecture-demonstration. The setting was next to a place where a number of local fishing boats are moored. The audience included many local people of Kochi. Many had probably not experienced a video performance, and they responded with enthusiasm. I was thrilled by this chance to communicate with some of the people living in Kochi.

About a year later, at another gathering organized by the TBA21–Academy in New York, I met David Gruber and started to read about his work. His research is fascinating, and I got particularly interested in it because of his focus on fish perception. In my own work, there is an underlying focus on how we perceive and how we see what lies before us in our world. In my performances, installations, and single-channel video works, I experiment with materials and simple technologies such as mirrors, distance in landscape, and/or video in order to alter perception and vision. So when I read that David is concerned with how fish perceive, and how he is developing ways for us to experience the phenomenon of biofluorescence in the deep sea, I was immediately drawn to his work.

David Gruber

The First Encounter

As a child and teenager, my early experiences with water were from the highly polluted Passaic River in New Jersey, a riverscape of abandoned factories that is considered one of the most contaminated stretches of water in the United States. I fell in love with the life of the river — its small fish (such as carp and sunfish) and arthropods that became enmeshed in my clothes while wading in it. This was how I first got to understand “nature.” As my world expanded, I’ve had the opportunity to travel to the most spectacular regions of our planet, including the deep sea. I’ve been consistently studying life from many angles: microbes, corals, fish, and plants. It is apparent how intertwined us humans are with these creatures, and my science has evolved to take on these interconnected aspects. I have also been very fortunate to learn about phenomena that had not yet been known to humans. One of these is the world of biofluorescence, how some animals who live in a blue-colored world have evolved ways to transform the almost singularly blue ocean light into a diverse spectral visual palate. This led me to wanting to better understand the world from the perspective of marine creatures, to see the world how they might see it. I was presenting this work at The Explorers Club in 2017 when I first met Joan Jonas. Joan was talking about works such as They Come to Us without a Word, which includes videos she had shot in aquariums. She mentioned she has a specific aquarium in Norway that she prefers, as it has local fauna and she can spend hours observing the fish. I was taken by the emotional aspects Joan brings to her art. While watching this footage, I felt her connection to the fish’s perspective. The work is multidimensional: sounds, mirrors, changes in distance and perspective, shots of young people performing overlaid onto the footage, and, of course, Joan herself. Experiencing Joan’s work evokes feelings in me that are related to my underwater experiences and deep connection to the submerged community. An inner fish.

The Continued Dialogue

We began corresponding in June 2017 and met again in Boston in April and May 2018, when Joan was on fellowship at the Gardner Museum and I was a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. She visited me at Radcliffe, where we discussed our respective perspectives. She shared videos of her work: Vertical Roll (1972), Waltz (2003), They Come to Us Without a Word and Stream or River Flight or Pattern (2016–17). And I shared videos of my underwater research. I also gave her a photocopy of Thomas Beale’s The Natural History of the Sperm Whale (1839), a text that inspired Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851). We met again at the Gardner Museum, where Joan gave me a tour and told me about a project in which she was drawing animals found in the Gardner’s collection. I enjoyed hearing her perspective on art and what she appreciated about specific artworks. I recall at first feeling very insecure that Joan would perceive my questions as pedantic. But this was not the case. It created an even ground for dialogue where I could ask anything I wanted about art; and she could of science.

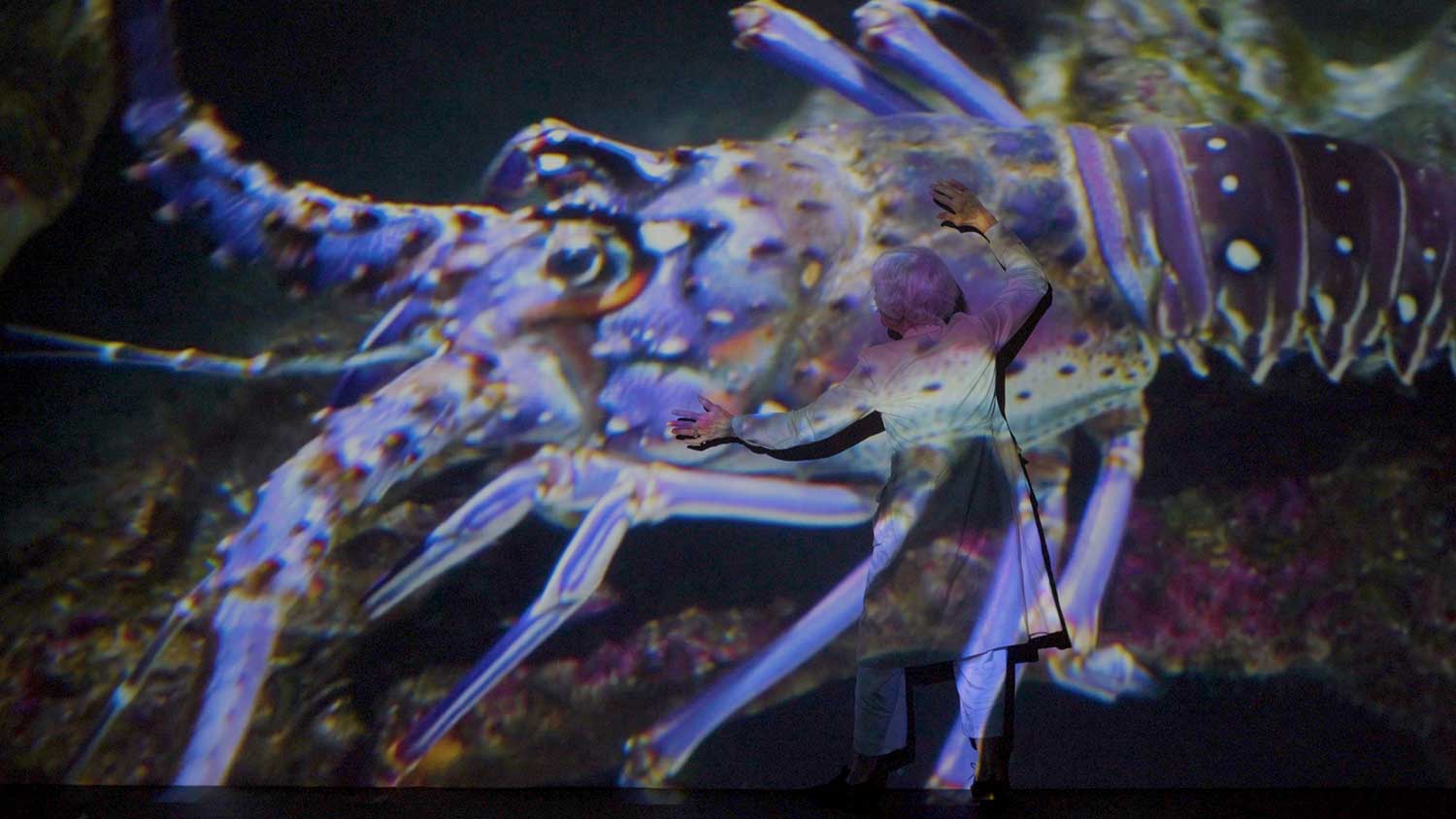

As I delved more into Joan’s work, I began to select which videos (of my thousands of hours of recordings) might be more interesting to her. This included my scientific videos of newfound biofluorescent marine species such as the lined sea horse (Hippocampus erectus), the weedy seadragon (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus), the hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), as well as biofluorescent corals and deep sea imagery my team had just taken of a rare Deepstaria enigmatica jellyfish, and the vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis). These were shot with a new low-light camera we developed, and had an eerie quality we’d not seen before. Within a few weeks, Joan had reimagined some of this footage into Moving Off the Land when she performed it once again, this time at the Tate Modern Turbine Hall in May 2018. That month, I used the same footage for a science publication, “In situ observations of the meso-bathypelagic scyphozoan, Deepstaria enigmatica (Semaeostomeae, Ulmaridae)” in the American Museum of Natural History Novitates. The hyperspectral footage from the “turtle-eye camera” project will soon be submitted for scientific publication.

From August 10–13, 2018, I visited Joan at her summerhouse in Cape Breton. On this trip, we had the opportunity to engage in extensive conversations. I also witnessed the deep connection Joan has with Ozu, her dog, and filmed him as he was playing with the surf on the shoreline. Ozu has appeared in Joan’s previous works. In her video Beautiful Dog (2014), he wore a GoPro camera hanging off his collar, which filmed the beach landscape upside down through his back legs. In Waltz, Joan’s previous dog Zina was the “howling star.” Joan and Ozu have a beautiful interspecies relationship. Witnessing their connection and Joan’s relationship to the land and sea of Cape Breton influenced how I recorded footage of Ozu and the sea life beneath Cape Breton. We rented a fishing boat and went out for an afternoon with many of Joan’s local friends from the area. We all went in the water.

In January 2019, we met again in San Francisco where Joan had an exhibit at Fort Mason and also performed Moving Off the Land. This was a magical moment for me as I got to sit in the audience and watch. While it is Joan’s piece, I could feel some of our discussions in the sub-layers. It reminds me of the covert underwater biofluorescent system I’ve been examining. The performance had been shown on several previous occasions. Yet in the way that Joan usually works, she continued developing the performance, added video material, excerpts of literary texts, and scientific findings.

After San Francisco, we met several more times in New York in early 2019, where Joan has a studio and I have a laboratory. We continued to share ideas about aspects of interspecies communication, but also discussed books and movies that we had independently read and watched. We also visited the Mystic Aquarium in Connecticut together, where she filmed shots of a beluga whale that have since become part of her performance as well as the exhibition in Venice.

By this time, I had become increasingly fascinated with whales, in particular sperm whales. Their story and trajectory is marvelous. They came from the sea (as did we), but then went back to the sea. They have sophisticated social structures and dialects, and have had their large, complex brains much longer than humans, allowing them added time to evolve. They are masters of breath, capable of diving over a mile deep and using that same breath to echolocate better than a nuclear submarine. These are animals that have been hunted for the spermaceti oil that is part of their sophisticated sonic apparatus. When I dive with them, they are gentle and inquisitive. A gaze into their eye is transformative. Very few people have had this opportunity. I played Joan recordings of sperm whales and pointed out their lexicon of clicks, clangs, creaks, chirrups, and codas. Some of these sounds have been utilized in “Moving Off The Land II.” I am now working alongside cryptographers and machine-learning experts to apply modern technology to seek out deeper layers and patterns in sperm whale communication. We are also designing new tools to study whales noninvasively. I’m interested in finding ways of altering our own human perspectives. I believe that only by doing so can we learn to cope with the ecological urgencies of our time, and acknowledge the manifold more-than-human perspectives coexisting with us on this blue planet. Joan’s working process, her performance, and exhibition, are powerful attempts to do exactly that.

Joan Jonas

David’s research on the language of whales is deeply fascinating to me. In trying to understand what they say to each other, we may be able to devise better ways of protecting them. And I feel it is important to know what we might lose.

I include children in my work partly because they will inherit this world and partly because it is important for them (and us) to experience the amazing complexity of ocean life and to know what might soon disappear. The children, or young people, recorded while moving and speaking in the projected footage of marine life, resulted in images that speak without words.

David’s footage in my work allows more people to understand the beauty of deep sea life. It adds another angle to the recordings I filmed in aquariums. Even though some of them try to simulate the “natural” environment of fish, they are still clearly human-made. In particular the imagery of the deep sea fluorescent creatures is fascinating and stunning. I am a swimmer but not in the deep, and I’m not a diver, so I could not experience the depths where these animals live.

Reflecting on the reactions from various members of my audience, I am touched that some people don’t realize that we come from the sea and that we are composed of the same elements. Our blood is salty, like salt water. I think people are learning when they see the performance, and they are amazed by the beauty of the fish.

In the piece, I talk about how fish relate to humans and how they communicate with one another. I mention how we have the same structure of semicircular canals in our ears as whales. Most people don’t know this. But aside from the factual layer of text, I also add excerpts from literary and poetic resources. I dance with the seals that are projected onto a screen onstage, and together with a performer, I try to catch the faces of fish with a circular shape attached at the front of a wooden rod. I’ve been influenced by shadow theater and traditional techniques of oral storytelling and epic sagas. These forms of narration continue to transpire in my work.

Thinking of when I started to become more specifically interested in the ocean, I come to think of a course I gave some years ago titled “Action: Archeology of the Deep Sea.” It was part of my professorship in performance and video at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I taught for about thirteen years. In the class, the students did their own research and I gave a subject to base the work on. I had been impressed by a book of photos of deep sea creatures. They’re so fantastic! So I decided to focus the course around this. I will certainly continue to visit aquariums even now that the piece is done. I also hope to continue the dialogue with David — the subject is vast.