Jessi Reaves’s New outfit standing container (all works 2019) is a darkling. Three antilopine console legs support an upturned, cankered carapace of blood-crusted contours; two of the supporting feet are folkloric pincers or scorpion tails that buttress the evening attire of a clingy brown fabric, whose insatiable slashes ensnare attention. Displayed in the window atop a carpeted, eggshell-gray ziggurat, New outfit declares: presentation.

Reaves’s chimeric furniture-sculptures perform pirouettes on observer and object; their twirls of deconstruction reassemble iconic or pedestrian design, pulling scavenged material into its whorl. While previous pulpy, Flinstonean forms were jury-rigged by chew-bones of wood, stapled foam, or stretched patchwork, the limning of simmering abjection or corporeal charm appears to have given way to something with more sheen.

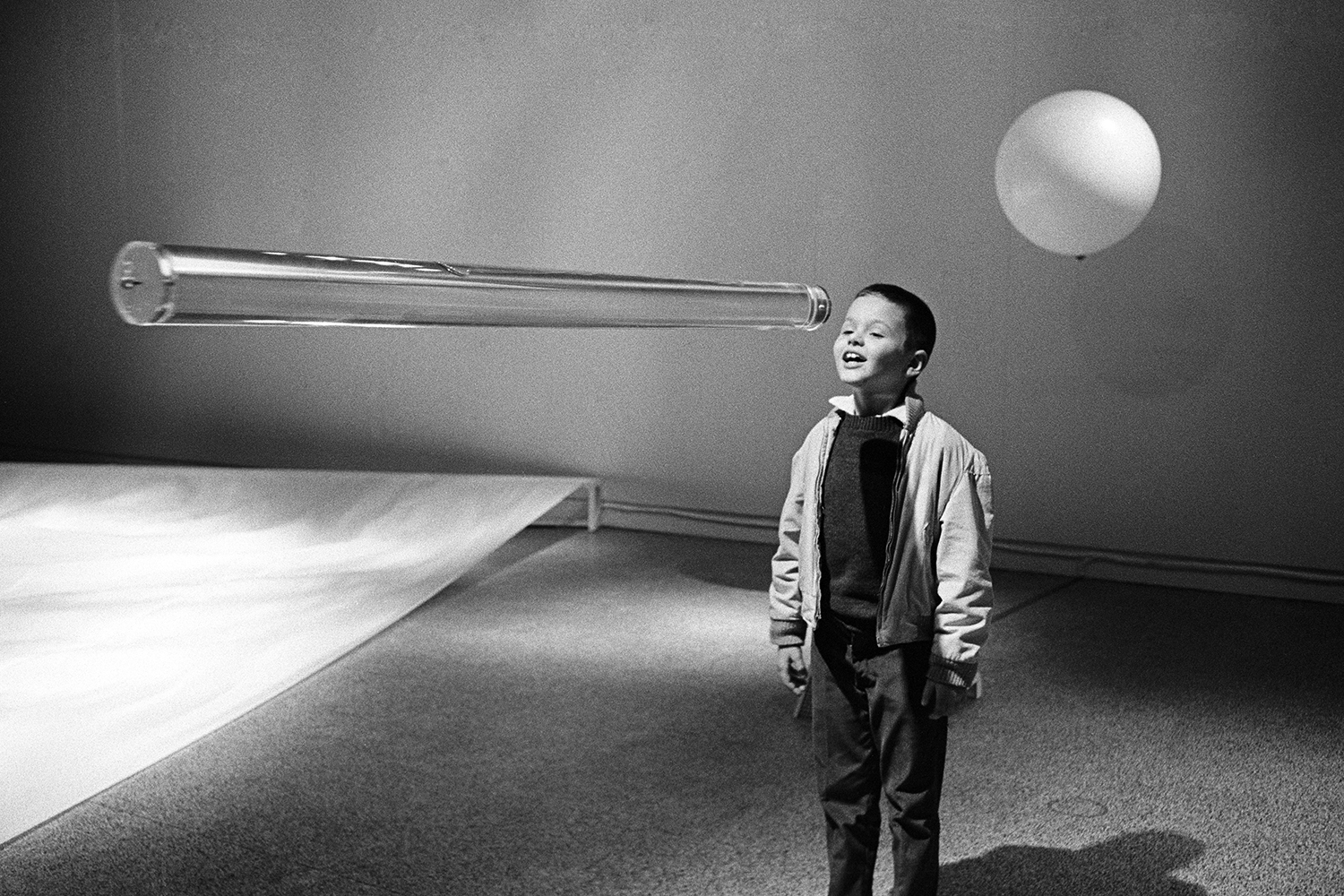

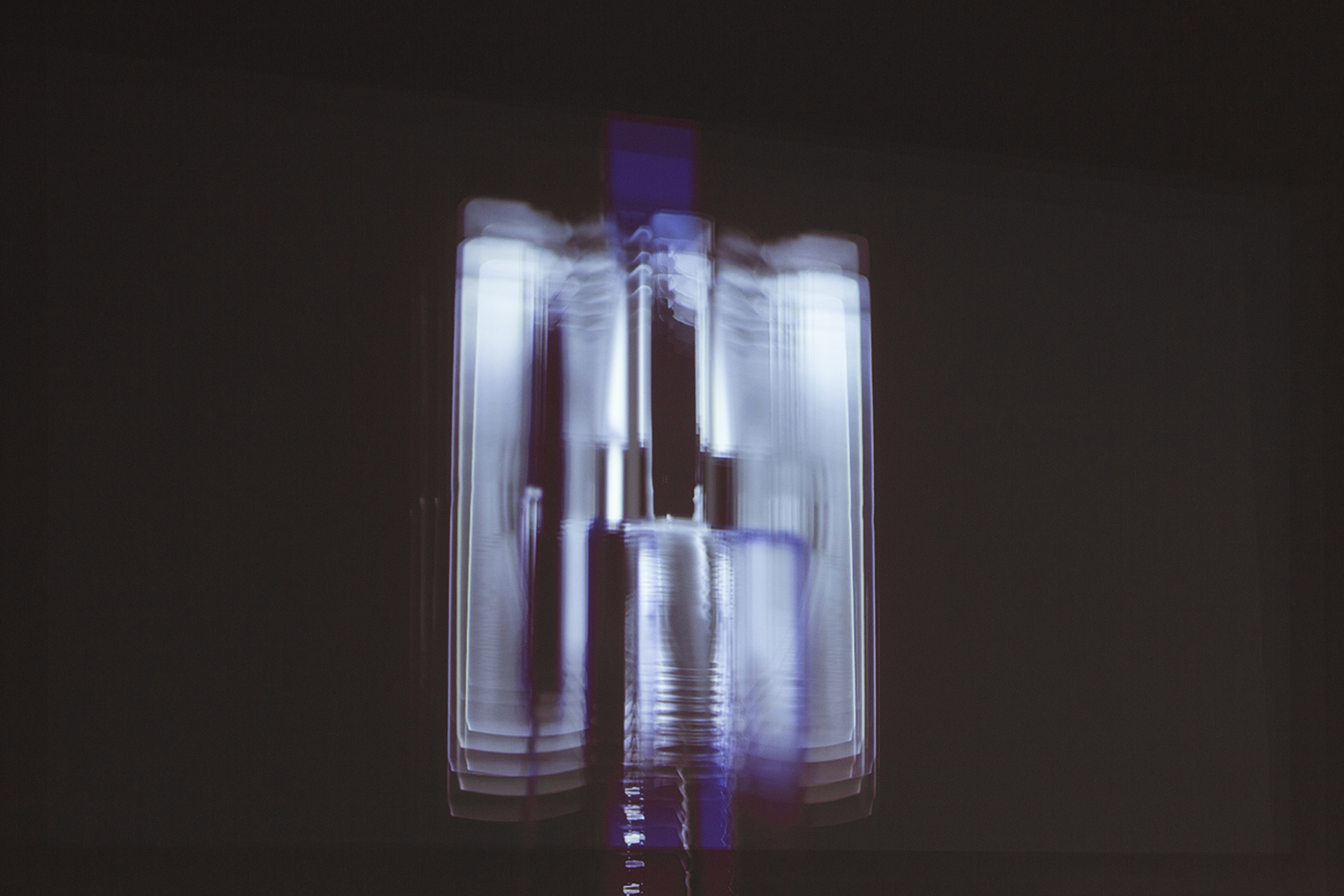

What is this something? Style, perhaps. Surplus character. The tiered carpet sections the exhibition in two; the remainder is populated with recalibrated chairs, tables, and sconces. Mantlepiece Sconce equips dismantled Isamu Noguchi Akarilamps with slogan T-shirts: “Stop and smell the rosé” reads one (achieving a weird aura of sizzling adolescence). A stretched canopy of leopard print is skewered by poles that create support systems for tentacular lights and glass teardrops. The glinting dewdroppery still preserves Reaves’s cacophonous hazard-play. This moment of sheen may just be a performative gloss: her doughy wood glue reinforces joints or blares into the “zombie cucumber” of tricksy datura flowers.

To go out in style rings of a death knell, and these works collectively oscillate between performative fashioning and a seeming acceptance of a last hurrah, acquiescing to preservation. Three bowl table supports bowls beneath a glass surface, with curved padded chairs that are themselves ensconced and sutured to the table’s arrangement. The work screeches reservation with gritted teeth. Similarly, Scrap jacket chair is placed atop a crimson plinth as though in anticipation of museological freezing.

The recess of Reaves’s tiered carpet frames the obsolescent fireplace; it’s a neat trick, which perversely reifies the surrounding sculptures, however baroque their inoperability. In their display of a conclusive glittering chain of progress — their strudel folds, melting drips, and lacerated holes of proud ellipses — these objects suggest an embrittled civilization’s swan song.