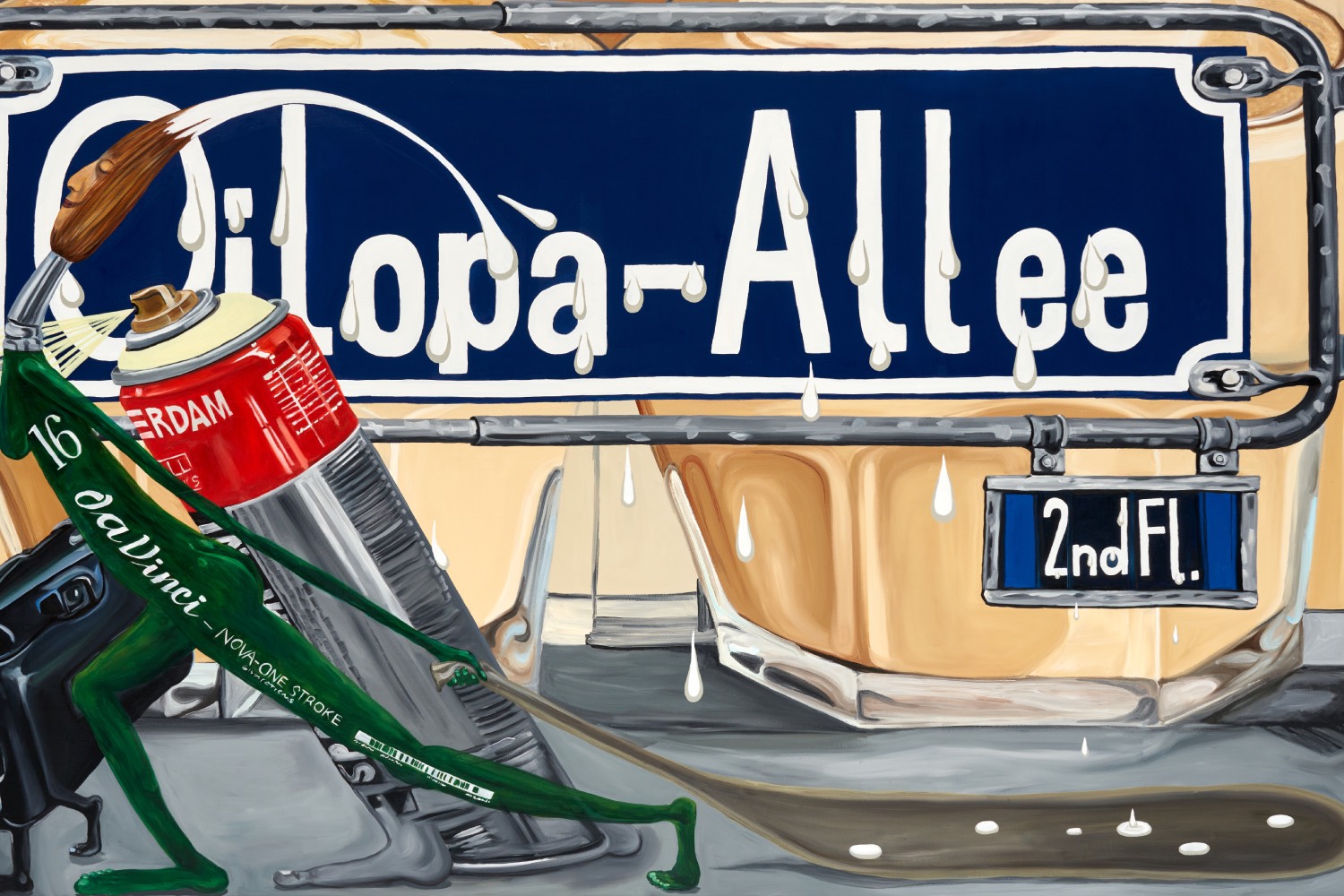

At a time of climate upheaval, when every action and gesture is examined in terms of its carbon footprint, it’s surprising that the world of culture — and the visual arts in particular — has never, or very rarely, considered the impact that organizing an exhibition can have. The transportation of works, the creation of scenography, the travel of artists and curators: all weigh heavily from an ecological point of view. With this in mind, Jana Euler’s decision to retain the structure of the previous exhibition at WIELS (dedicated to Jef Geys) is far from insignificant. The idea is to reappropriate a space while avoiding the use of new materials. This is why she cut out the walls, tracing a diagonal line through the whole of the building called “Oilopa Allee,” a reference to Frankfurt’s Europa Allee. In this way, Brussels, the seat of the European Commission, is metaphorically connected to the city that houses the European Central Bank.

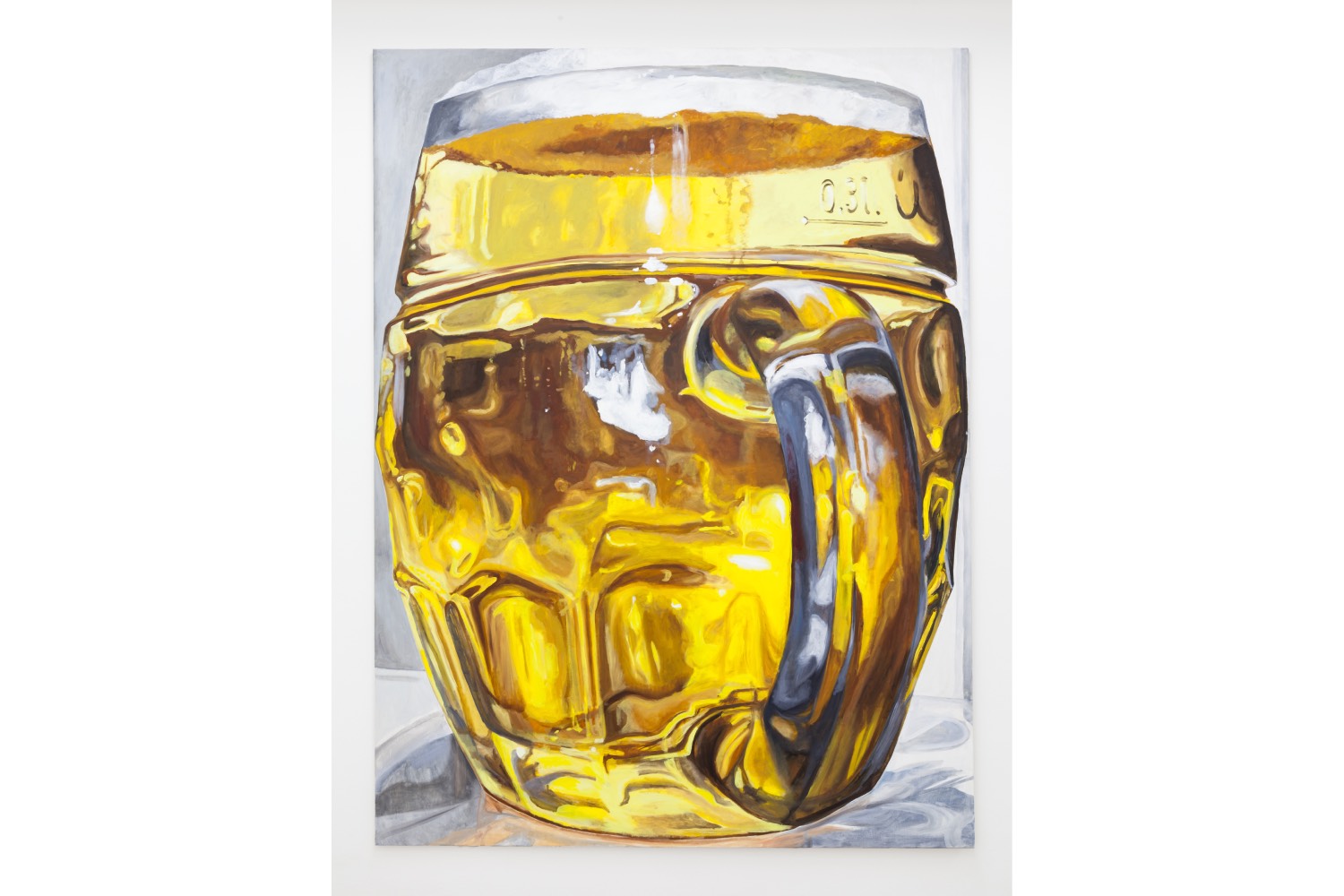

With this “box within a box” containing her paintings, but also photographs and sculptures, Euler questions both the status of painting and the way in which the art world is an economic player in its own right. A large painting depicting a beer mug (Beer without Glass, 2013), for example, reminds us that WIELS now occupies the buildings of a former brewery, which was very profitable in its heyday: the art economy has replaced that of the fermented beverage for which Belgium is so famous. It should be noted that the City of Brussels has just inaugurated a beer museum in the former Stock Exchange building, a project criticized by those who would have preferred to see an institution dedicated to art.

The title of the exhibition itself refers both to the hydrocarbon trade, on which our societies are still heavily dependent, and to the technique of oil painting. For the occasion, Euler revisits some of her favorite themes, such as phallic sharks leaping out of the water. Here, a dolphin jumps diagonally across a blue background, creating a strange visual reminder of the Deutsche Bank logo. A new series features oversized coffee beans, one on each canvas, like specimens under the microscope. The subject matter is not insignificant, at a time when the price of robusta is reaching record highs due to poor harvests in Vietnam (the world’s leading producer) as a result of climate change, coupled with growing demand from China. But these paintings also refer to the notion of “cappuccino urbanism,” a form of urban uniformity that is a corollary of gentrification.

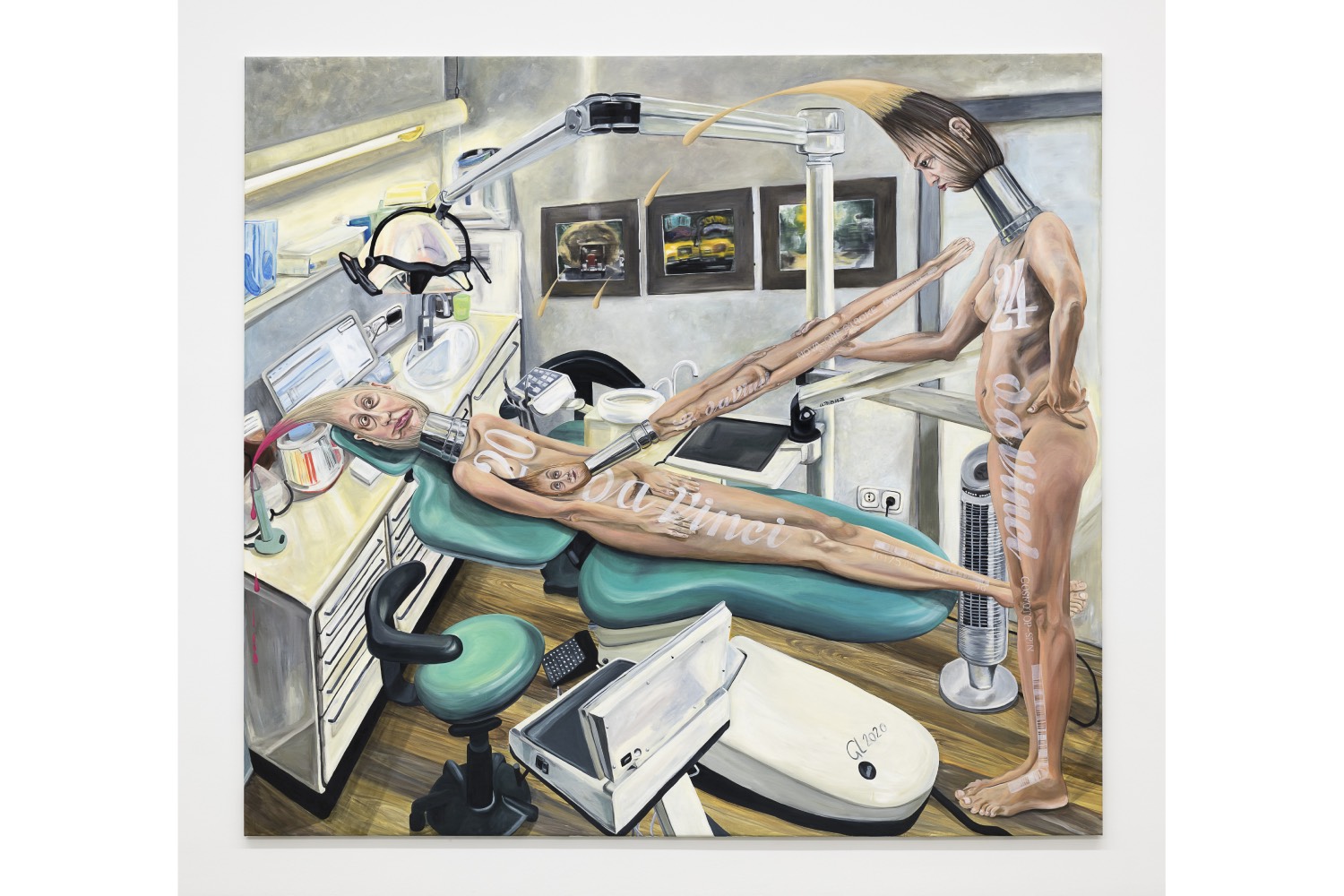

Euler illustrates this theory with a series of photographs of buildings such as those found in all the world’s business districts, glass facades next to which we often find cafés with decor inspired by Brooklyn’s neo-industrial aesthetic. With these images curiously suspended in their metal frames — an ironic nod to the Düsseldorf School — Euler reveals the humorous dimension of her project. “Oilopa” is more an installation than an exhibition, in which the works are not identified by labels. Yet it is painting that remains the central subject of the artist’s reflection. Visitors are greeted by a large canvas depicting a compact camera, evoking the hyper-realist aesthetics of the “oilopa.” Elsewhere, anthropomorphic da Vinci brushes celebrate the technique of oil painting but stand side by side with airbrush paintings. It’s also in this part of the exhibition that we come across the Forward but backwards running Morecorn (2022) — an inflated unicorn seemingly drawn backwards by a retrograde current, against a blurred background that seems to be taken directly from a Gerhard Richter painting.