Vít Havránek: In your theoretical texts and live performances the artist is perceived as ‘Homo Politicus’ and political self-identification has for several years been at the center of the debates that we participate in. To what extent are political issues present in your works?

Ján Mančuška: It’s a particular reaction to the climate of the ’90s in the Czech milieu. The generation before me was united by a common aversion to a political perception of their work. It was logical in view of the situation in the ’80s and the doctrine of passive resistance to the previous regime. Actually, consistent apoliticism after 1968 was a form of opposition shared on the artistic scene. This was the case of Jiří Kovanda. It was to a certain extent strongly political to be non-political. Being apolitical resulted in one interesting thing: everyday life became strongly politicized. This is also my background, but it is not in itself enough for me.

VH: Could you explain this paradoxical claim of an apoliticism that politicized the everyday, and does it relate somehow to Giorgio Agamben’s “Form of life,” for example?

JM: I feel a need to formulate the things I do that work with the environment of everyday life in the sense of a political discourse. I have to say that I share the trauma arising from what happened at the end of the ’30s: the avant-garde was thrown out of its social and political program, both by Stalinism in the Soviet Union and through its relocation to the US, where it became a narrowly elitist discipline.

The question is: how can this heritage be overlapped? One method explicitly formulates a concrete political standpoint. I would call it the ‘illustrative model.’ There is obviously a wide spectrum of artists dealing with this, but out of all of them I would name Artur Żmijewski. My problem is that at the moment when this type of artistic production stands face-to-face with real political problems, which it is perhaps expected to outline a solution for, it fails. And at this moment it somehow devalues the authentic potentiality of art and returns it to the province of sophisticated, academic entertainment, and the reactions of the people who find themselves within the given situation are disappointment and subsequent disinterest.

My opinion in contrary is that the artistic act as such contains political meaning. That’s where its strength and self-confidence lie.

VH: That is one of the paradoxes noticed by contemporary political philosophy as well as postcolonial theory. Gayatri Spivak in one of her texts reflects on the separation of theory and political representation. The articulation of the subaltern person that she performs in her texts does not mean that the life circumstances of subaltern women will be improved, or will continue to improve. The only way of improving their situation is to find a temporary political representation for them. Is the transcendence of theoretical antagonism into political representation possible? And how does contemporary art define itself with regard to this relationship?

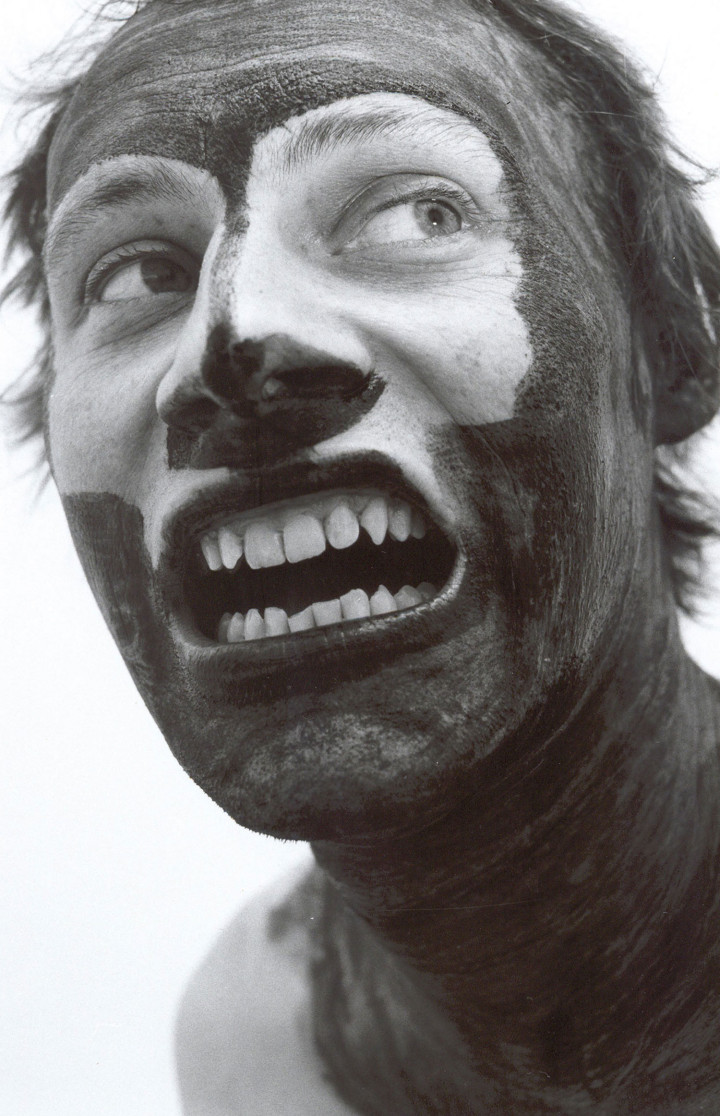

JM: I’ve always been interested in working with the subsoil on which political identification is realized, in working with the most fundamental circumstances as, for example, in my work entitled The Other (I asked my wife to blacken the parts of my body which I cannot see) (2007). The fact that my model, my fictitious alter ego, in the end had an entirely blackened face was a powerful experience. The part of the body that is absolutely fundamental for our identity, which represents us as citizens, social beings — the face — is one that we ourselves do not see.

VH: In your recent works a certain duality emerges even more strongly. Irrespective of the medium, there are two layers present in them: one is focused on the body, on the physical movement of the spectator in real time in the space of an installation, an interactive situation in a cinema, in a theater, etc. Alongside this sensual, physically expressive element, a motor of deconstruction of the flow of the story, or rather a theoretical apparatus of deconstruction of narrative is activated. How do you see it? Is there an attempt to connect these two layers?

JM: The collision of these two principles of consideration is always present in my works: the conceptual, which begins with the critical delimitation of the medium, and the existential, which often refers to incarnation or narration. During the process of emergence of these two things, I perceive them separately for a long time and work with them separately. The concept as such always emerges on its own, and the story either emerges on its own, or an already existing one is selected. The moment at which these two things meet is then fundamental.

VH: Did the deconstructive apparatus come about to demolish the universalism of the story, to fragment it and actually deprive it of universal, humanistic application? And must this act always occur individually for the viewer while moving through the installation or exhibition?

JM: The objective I am aiming for is precisely that this should happen at one and the same time. It is a really strong moment for me when the viewer experiences this conflict synchronously. To a certain extent it can be interpreted as a reaction to development in postwar art, whether fine art, dramatic or performative art. At the end of the ’60s, following the New Wave and the New French Novel, the story did not seem very topical. It is clear from later developments though, that everything was ultimately different. I am interested in the story as a phenomenon.

VH: Do you return to the story as to some ethnographic (and therefore universalist?) constant, to an archetypal equation of expression?

JM: It is precisely that kind of pre-historic or pre-cultural character of narration that interests me. Memory has, and must have, a selective character. It selects from the disorganized and the ongoing, from that which has become fragmented and broken up into details and, in order to be comprehensible, it must put them into some kind of structure, which in my view has right from the outset the nature of a certain dramatic form. But in my interest in the story I subject narrative form to conceptual criteria.

VH: When you work with true stories, are they in a sense ‘ready-made stories’?

JM: Just so. Actually though, I haven’t worked with fiction for a very long time.

VH: To what extent is it important for you where these stories originate, culturally or geographically? Can we also view them through the prism of history, ethnography, political science, sociology, etc. with regard to the place in which they took place?

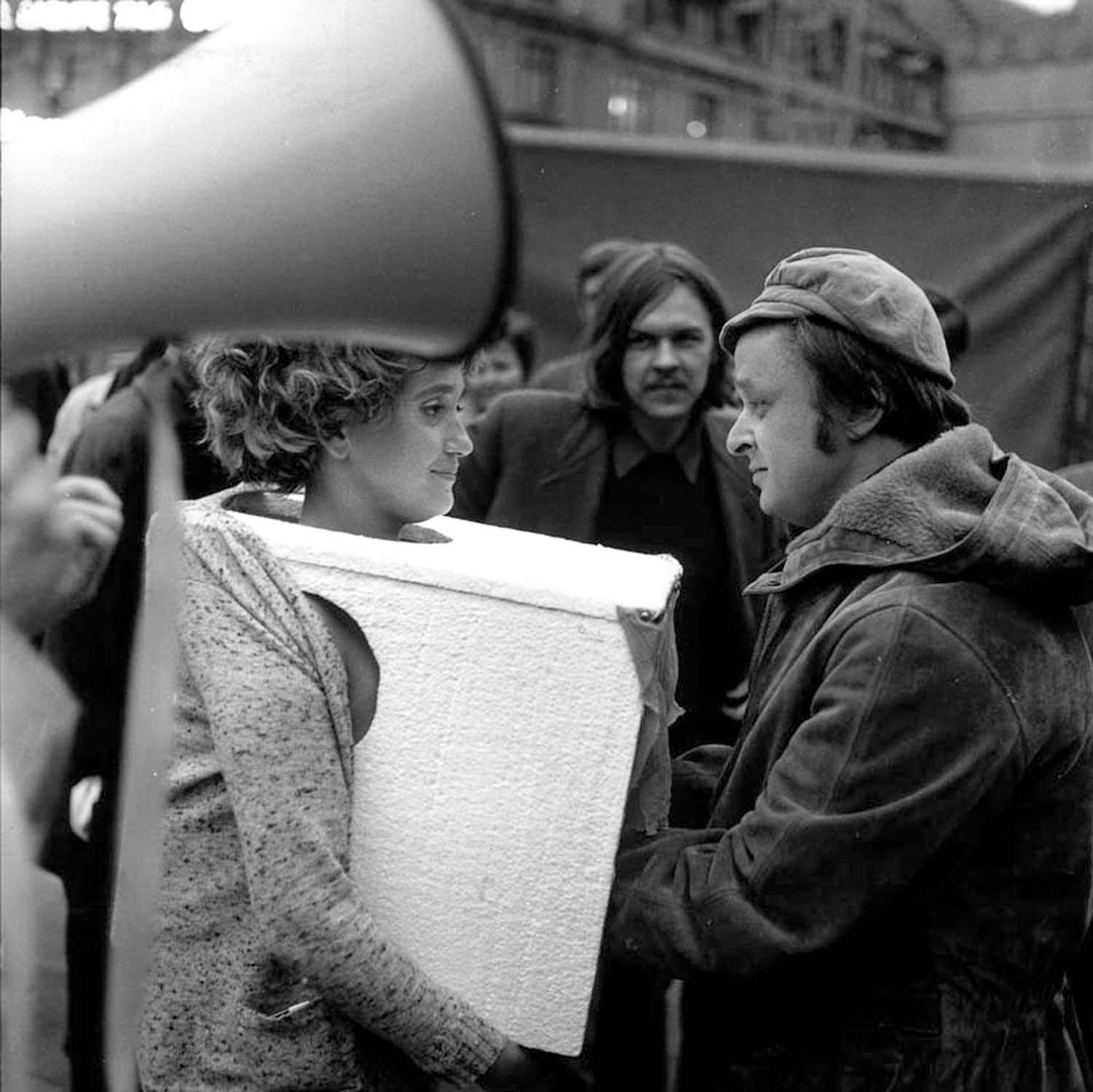

JM: For a long time I developed the concept of ‘immediate context.’ By this I meant the environment where a certain form of obvious understanding occurs. For instance, in Prague there’s been a department store called Bílá labuť [The white swan] since the ’30s. When they hear this phrase, all Praguers know that it refers to the department store although it has nothing to do with an actual swan. In my opinion it is very important for an artist to somehow preserve this quality. The position of the international artist lays into the superficiality of the global art system. On the other hand, local contexts are very problematic as it happens for ‘East European art.’ I think contemporary art deals with this conflict through the new use of gestures which sometimes seem almost theatrical. I call this environment ‘staged reality.’ It is the thing that led me to performance.

VH: In your works, the story, textuality and the media of depiction (object, installation, video, film, theater) undergo deconstruction, but at the same time there is a faith in the potential of signification of artistic forms.

JM: The one should again make the other problematic. My earlier textual installations worked with text as an object in space. And they were the bearer of the visual. But right from the outset it was clear that this strong visual form is misleading, that text is primarily the bearer of content. Actually the form was undermined by the content and vice versa.

In the case of my film sculptures (for example the work Oppression of an Initial Figment) (2009), it is exactly so. At first sight it seems that it is the perfect formal side that is fundamental for them. When you study them further though, it should be gradually more and more clear that the shapes in which the films are formed imitate the movement of the actors/figures in the photographs, for example the path of their walk, that they therefore refer to something else. And beyond that you realize that it is actually a storyboard for the text that is written on the walls around the installation. One of the principles employed here critically undermines and deconstructs the other.

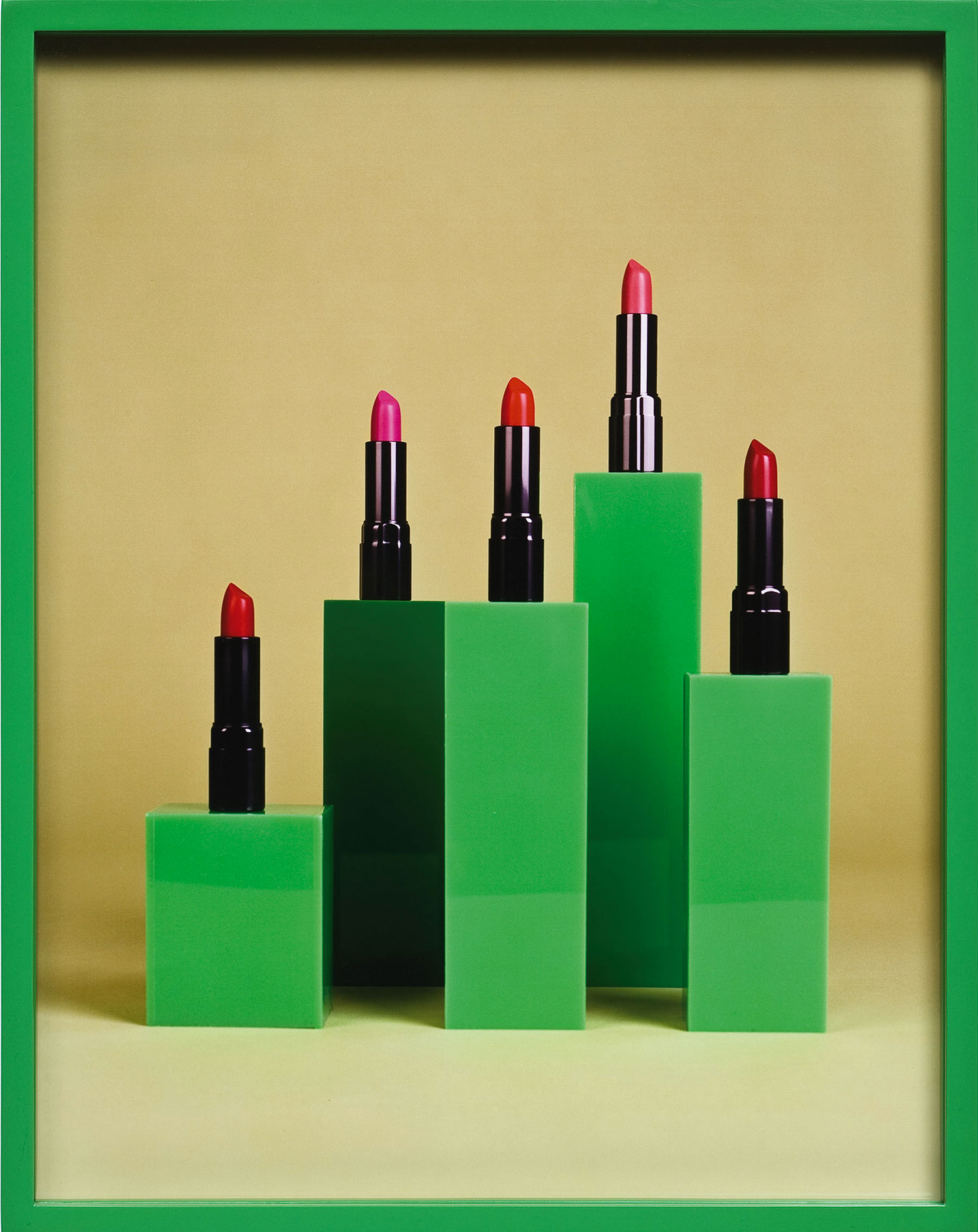

It is similar with the last thing I did. It’s called This is how it really happened (2010) and consists of two slide shows in a special installation. One of them is again a text piece. It is composed of photographs of a still life, in each of which is concealed a fragment of text, words, etc. In the correct order, the photographs then form a coherent text. These photographs again have a strong visual aspect. I see them to some extent as my coming to terms with the legacy of Bauhaus. But the photograph itself is somehow stripped of relevance, because in the overall composition of the slide show it is only a fragment in a subordinate position to the whole.

VH: When one follows your work over a longer period, what seems constant is your interest in narrative, while the always carefully constructed form is very mutable and we cannot find a unified aesthetic code in it. Why do you reject some stable aesthetic code?

JM: In this context I like what Alain Robbe-Grillet wrote about Roland Barthes; that what he was striving for was a constantly reinitiated movement that could never become an institution, because it exists only at the moment of its own origin. For me that defines the idea of freedom. It could be objected that subsequent development in art proved that even this could become an institution. In my opinion though, that’s a misunderstanding of this idea. But I have a feeling that in my case it’s about something else. In a certain respect I’d call my work ‘ontology of media.’ Several times I have processed an identical text or concept in various media: first as a text piece, then as video, as a performance, and then as an animated film within a spatial installation. The Other was exhibited first as hanging filmstrips with a light box as well as a performance. I do this because I am interested in the extent to which the chosen medium plays a role in the specific piece — to what extent the medium transforms the material used and to what extent it’s inevitable.