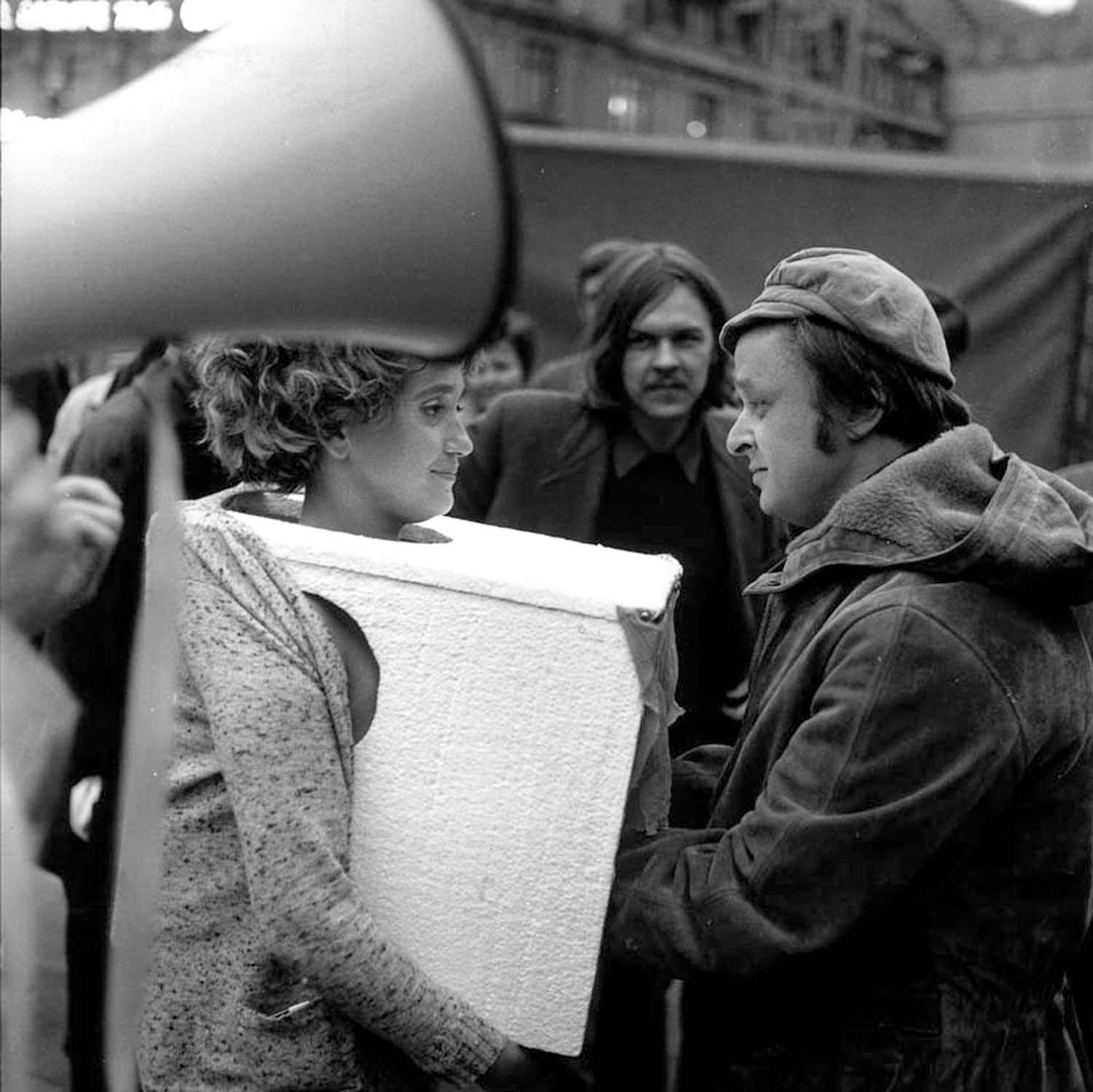

Florence Derieux: You created your own production company, Kick the Machine, right at the beginning of your career in 1999, and you started simultaneously to be active in the fields of cinema and art, participating in many film festivals as well as art biennials. You have since produced books, images and installations as well as feature films. How do you articulate this? Do you work differently according to your productions’ area of reception?

Apichatpong Weerasethakul: What I do echoes one another and relates to a few subjects of my interest — such as memory, transformation and duality. Sometimes the video that I produced resulted or found inspiration through research for a feature film, for example. This cross-platform working style in itself reflects, again, the idea of transformation, mutation.

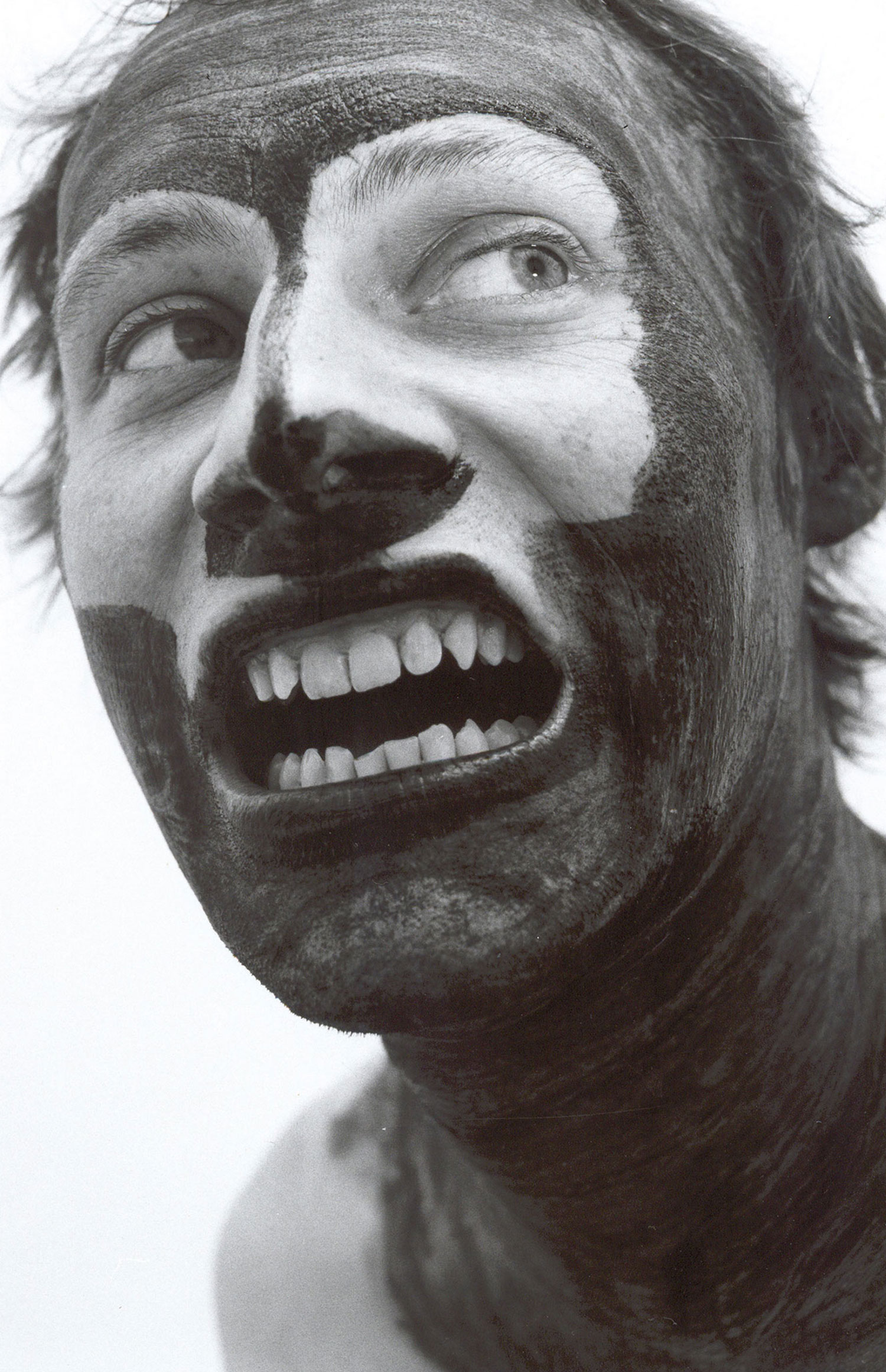

FD: Your films are set in Thailand; they mostly involve ordinary people instead of professional actors, and are often put together in an improvised manner, which gives them a very natural and fresh feel. Besides the recording of reality through specially chosen colors, tones, sounds and rhythms, they seem to also include other realities. In fact, your films are often described as ‘dreamlike.’ However, the organic flux which you create between different realities — between documentary and fiction, emotions and events, past and present, for instance — gives rise to a particularly distinctive work that is perhaps more spiritual than oneiric?

AW: You mentioned the word “organic”. That’s how I orient myself towards each work — to let it branch out like a vine. So the working method is fluid. I like the ‘in-between state’ — reality and fantasy, acting and non-acting, cinema and installation. I think that when the audience is aware of this state, their mind is free, not bound to form. So there is this sense of openness that allows drifting.

FD: You once said: “Not everything can be explained through words.” Actually your films never focus on a specific topic but seem instead to manifest a sort of state of the world that would no longer dissociate the real world and the spiritual world. What exactly is your working methodology? Is it true that you sometimes use the advice of fortune-tellers, for instance?

AW: I am open to chances and encounters. I ask for people’s advice, fortune-tellers included. I guess it is mainly to stimulate, to create a memory of the ‘making of’ the movie. The filmmaking process is such a big deal for me. The script is just to apply for funding.

FD: The Hollywood Reporter claims that your films deal with the supernatural and with past lives.

AW: Yes. A new movie is a reincarnation of a previous one.

FD: Can you tell us about Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, your last feature film for which you won the Palme d’Or in Cannes this year?

AW: It is inspired by a book given to me by a monk. It tells a story of this man who keeps being reborn in the northeast, where I grew up. I wondered why he had to be there, a dry place with lots of political manipulation. Then I realized that he was trapped. So I wanted to make a movie about trapped souls, with this region as a backdrop. It is also an homage to an old kind of cinema that is disappearing, dying, like the main character.

FD: You often use fairytale characters — animals, princesses and so on — which can immediately be appropriated by all, although your films always seem to avoid the traditional structure of fairytale. What is your relationship to popular culture?

AW: Our animist belief is here to stay. I always think that if the Thai government can build a rocket to Mars, it will bring back Martian rocks and turn them into amulets, and they will be sold out immediately. The Martian God will be a witness. This is my kind of popular culture.

FD: Tropical Malady (2004) is a diptych, like many of your works. Why do you often use this type of construction?

AW: It’s because of the recurrent contrast that exists in Thai society, I guess. The landscape is changing fast, but the beliefs remain the same. There are these ‘push and pull’ tensions of moving forward and backward. There’s a co-existence between the two poles.

FD: With Syndromes and a Century (2006), for example — which surprisingly was censored in Thailand in 2007 — your project can perhaps be described as an attempt to recreate an imagined past within an ever-changing world. Can you please tell us about your obsession with the fabrication of images and memories?

AW: It relates to my obsession with trying to record. It is possible that, because the past is disappearing — the city where I grew up has changed drastically, my father is gone, moviemaking as I know it has been changing — I feel a need to preserve it while all the images that are in my mind last. Basically they are my diary entries. It is a particular kind of diary because the present is mixed in with the past entries.

FD: The video My Mother’s Garden (2007) seems to be based on the same premises. However, it also seems to reflect your very distinctive capacity to move between every creative field and their specific history — art, cinema, design, fashion, etc. — in relation to globalization. Can you please tell us more about this work and its status?

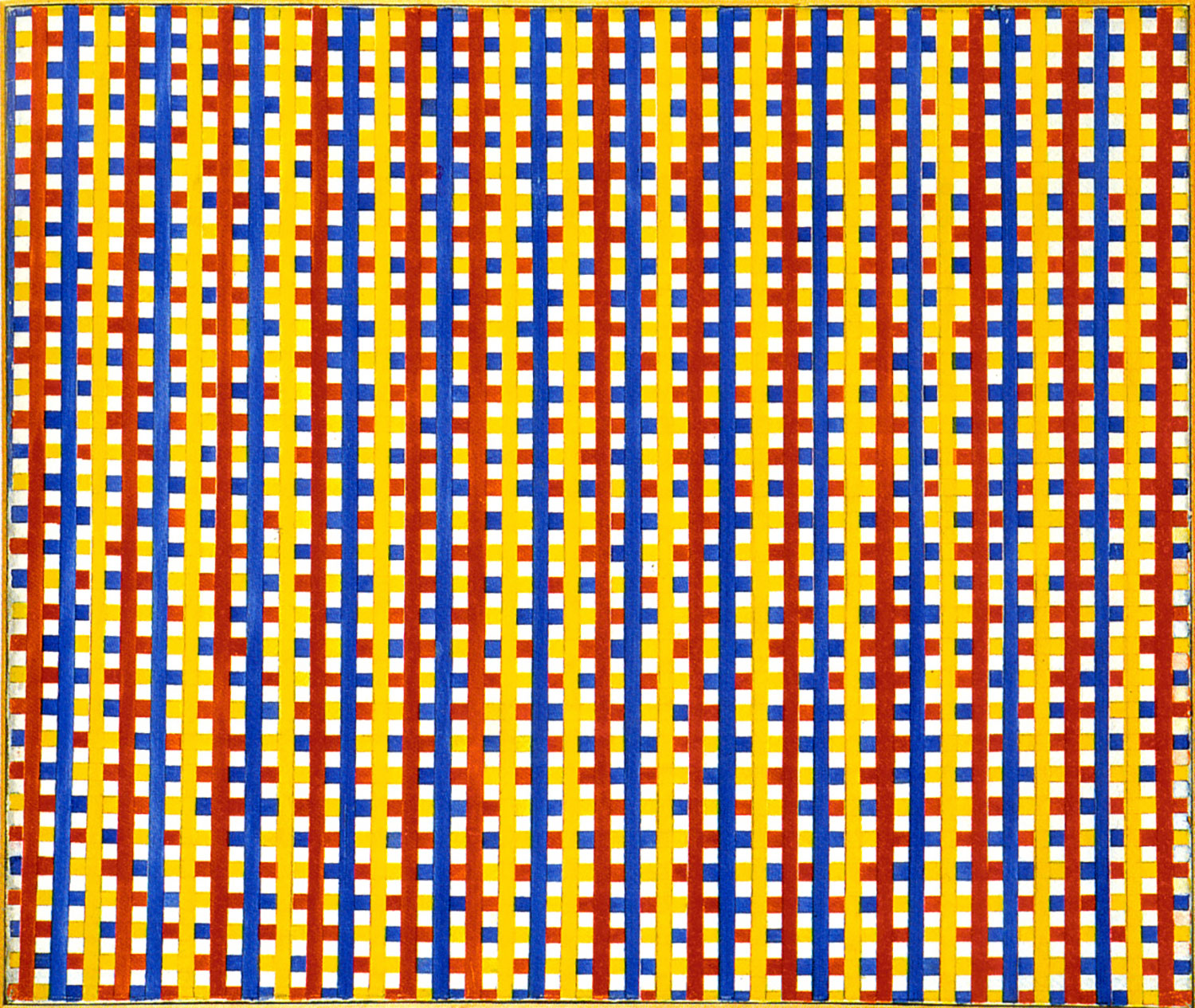

AW: My Mother’s Garden is a commissioned work whose purpose is to celebrate beauty. It is a bit different from my other works. The video comes from my impressions and reactions to the jewelry designed by Victoire de Castellane — she is such an incredible artist. Her workspace is full of tiny toys, of colors. It is my impulse to look at minute details of the plants and animals that inspire her design. Somehow I feel that this work is created from a child’s point of view. It is both delicate and raw. I brought up my memory of my mother’s orchid garden, with its soot and wires and insects. I introduced some simple animation elements, mixing the colors of the flowers with those from the jewelry.

FD: In a recent interview you predicted the end of cinema and said that new forms of images and narrations will soon appear that will no longer be called cinema. Can you tell us more about this?

AW: I am not sure about how ‘soon’ this will be but I just think that, even though cinema is young, maybe it will die young. Or, let’s say that it will transform. Maybe it will be in a form of self-distribution for self-consumption. Maybe it will become a private affair.

FD: I’m also curious about something you said recently about wanting to adapt all books by George Orwell.

AW: Did I say all books? Maybe all books into one film? After his novel 1984, I have just begun to read his less known writings. I think his stories have dualistic elements, fact and fiction, and many playful yet serious characteristics that make me dream.