Diary entry from a lion in the back of a wardrobe, May 10, 2023:

It’s been a long day, entre-nous. My dreams are toothless, gold, and the quiet unnerves me; I’m worse for wear. We’re all sinking, making covenants with the idea that we’re not struck down by uneasiness, which is always compelling. What’s something fantastic? I wouldn’t know — there is no bigger picture. I’m a person with many crimes, countless undiscovered, and time’s run out on most of them, which is fine by me. You can never wholly trust that things will stay the same, that people remain the same, or that ideas will endure because they never do. It’s a pretty impressive subterfuge, and I more or less wheeze in admiration at the cleverness of it all. Twenty thousand miles have passed since my last self-iteration from the week before last, and strengthening the resolve to toughen gets weaker by the hour. Surviving is the same as living, no matter what they say.

Catching a second or third gale wind for her solo show at Lafayette Anticipations, American artist and musician Issy Wood pulls up to the curb in a mile-long Paris cab with mile-long radiance. Hers is a light that shatters and kills. Wood has spent many hours making abjection a nom de plume, but it’s a far sweeter, exigent wildness that coolly watermarks her figurative work, books, and music albums — nothing’s more depressing than a total Renaissance woman. She’s so disgustingly countable and reliable, fingers in every goddam pie, licking them with sequined tongue and time-traveling ash, searching for ways to control the world and herself with all its many iterations. How many horoscopes does a person really need?

Bidding is closed

Issy Wood swings wildly from a state of sheer and inexplicable ecstasy to inhabiting Sylvia Plath, who was writing early dawn, getting into petty disagreements with herself before her babies woke. Making art is a dangerous endeavor. Laying down on a bed wearing blue-valentine veneer in her painting Rory, Lying In (2015) is a raven-haired girl, asleep or dead; you never really know. Ambivalence is a far-sighted pursuit. The painted figure looks relieved, quite frankly. Relief from a lifetime seized by shy springtime winds and the lukewarm intrusions of attention, its every unwelcome incarnation unraveling like a long listless survey piece. She hasn’t much time to weigh the alchemic gains and losses of moody-blue life and sapphire death. Muddied light refractions kiss her olive face in Rabelaisian gestures, back hunched, cloaked in defeat, and unmade sheets pressed stiff with cornstarch, stardust, and halogenic chlorine. Lady Rory will miss some people who warmed lifeless cockles with restraint and quiet notions, but they’re now out of reach, and it cannot be helped. It’s a figurative reminder that grief needs to be transactional, that grief is not transient nor contingent, and that grief craves language, even if that language is simply an acknowledgment of not having adequate language. A languid raven-girl with a passion for emptiness and nonexistence, but it’s scant compensation when the emptying is done without your consent. She’ll try to try again, to rise like Lady Lazarus, scrawl on millions of white filaments, peel off the frost of midnight and make her own glitter of seas. She lifts seashells to her ears and watches the light turn coral. She’s almost completely nocturnal now.

But that was yesterday

Issy Wood hardly remembers life before, when living was viable momentarily, and she could bank on death being a sibylline deviation. It’s been a long day without you, my bosom friend, sadness. Wood pulls teeth with excruciating slowness in paintings Sore awards 1 (2022), Metal / Diary (2022), and My consequences (2021) for her solo show “Time Sensitive” at Michael Werner Gallery in 2022. My consequences blurs oil onto panne velvet, depicting premolar teeth in metallic gray and crème brûlée. Catching acuity, they are, in fact, impacted wisdom teeth, rotted cavities burrowing deep into the marrow of dental pulp, igniting nerves, arteries, and temperamental veins, setting them on fire. Teeth cannot grow back. Wood is a sensitive artist with just enough artistic wisdom to know that the essence of things is irreplaceable, that the epilogue of agony and its voyage south is unrelenting. Sweeter times materialize most when you’ve started to die.

Days of discipline when we dream of falling.

Struck down by psychological uneasiness and the pointlessness of living, Issy Wood browses in lost places under calcification, metallic air, fainting prasine buffalo, discount lobotomies, and philatelic messages from the afterlife. Her teeth paintings (and there are many) brace themselves with chainmail fillings of zinc and liquid mercury; it’s poison, love philter, thoughtful dementia, palliative care. She’s a slave to unrespectability. Yet mercury is a metal-filling armor that’s visually stable and predictable, with half-lives that she can control: isotopes that will never, can never, deteriorate. At least in her lifetime. Wood’s undeteriorating dedication to molars and leaden decay survives for the front cover of her 2021 EP, If It’s Any Constellation, depicting a set of perfectly aligned canines and incisors with metal braces. Braces, as we know, are a (very) rich man’s sport, but metal braces are for the level rich that can’t quite afford clear, invisible aligners from privately insured, dinero-eyed orthodontists. The NHS has plenty of other necessary medical interventions that they take care of. Just ask them. If there’s any consolation to Wood magnifying the maiming of pliant bodies, it’s that her cover image and lyrics reach for the unwiring of beauty standards that are tortuously concocted, regulated, and politically misaligned. Constellations are unnecessary dot-to-dot diagrams bridging stars close to and far from Earth into eighty-eight moronic pictures of straight-lined animals, objects, or astrology. Which is precisely what Wood isn’t interested in doing. Rocking in the fetal position, Issy Wood explores blind deference and intractability through dentistry (and the embarrassment of horoscopes), highlighting caustic beauty ideals and socioeconomic disparities that orbit our unconscious and are so ingrained in the social fabric that it’s hardly remembered. Wood appears to care about the starry-eyed dilations of patriarchal evisceration so much that she takes the time to (finally) capitalize one of her titles. She pulls a grotesque face at the astral controls and deposits of the patriarchy, and if a sudden wind should change, it’d stay that way. Total success.

Wood’s augmented teeth, étoiles, control, and breastplates of righteousness constantly remind us of the extent to which belief systems, social ideologies, or even experiences can be progressive or syncretic at their edges. It’s really the core of existing that’s rotten in some sense, so she makes it her business to draw outward to the margin toward solid materials that cannot erode and pools of incandescent light. Yet moving in her paintings, there’s no wind, a sequence of stillness to stillness, of breath, small, quiet gasps issued by mouths, unmoving. Through gritted teeth and political cognizance, Wood muses the weighted pathologies of enamel and brackish spittle with her dirt-filled nails and dutifully honied voice in timeless dissociation: “They (teeth) are a diagnostic tool. You can tell how happy someone is from their teeth — if they grind them, if they’ve been damaged by acid erosion,” she says with patchwork jurisdiction. Understandable in light of her combat with eating disorders, namely bulimia, in which briny, astringent bile corrodes teeth and a sense of control. Eating disorders are all about control, and there’s no madness more honest than grappling with its mirage. Effortfully, she spits back in affectation from a psychiatric ward at the wages of hegemony, exposing the (woefully misunderstood) social and mental pressures of regulated self-erasure. Wagging tongues at the catastrophes of her limits, Wood wields self-effacing humor, taking pleasure in sadness, keeping guard over our liberty with an artistic dedication to the illusions of control. Hiding despair and cynicism under an overcast, noontime pillow brushed by Jacques Lacan, Wood waits for dry-witted tooth faeries to take it away.

Waiting for payment that may never arrive

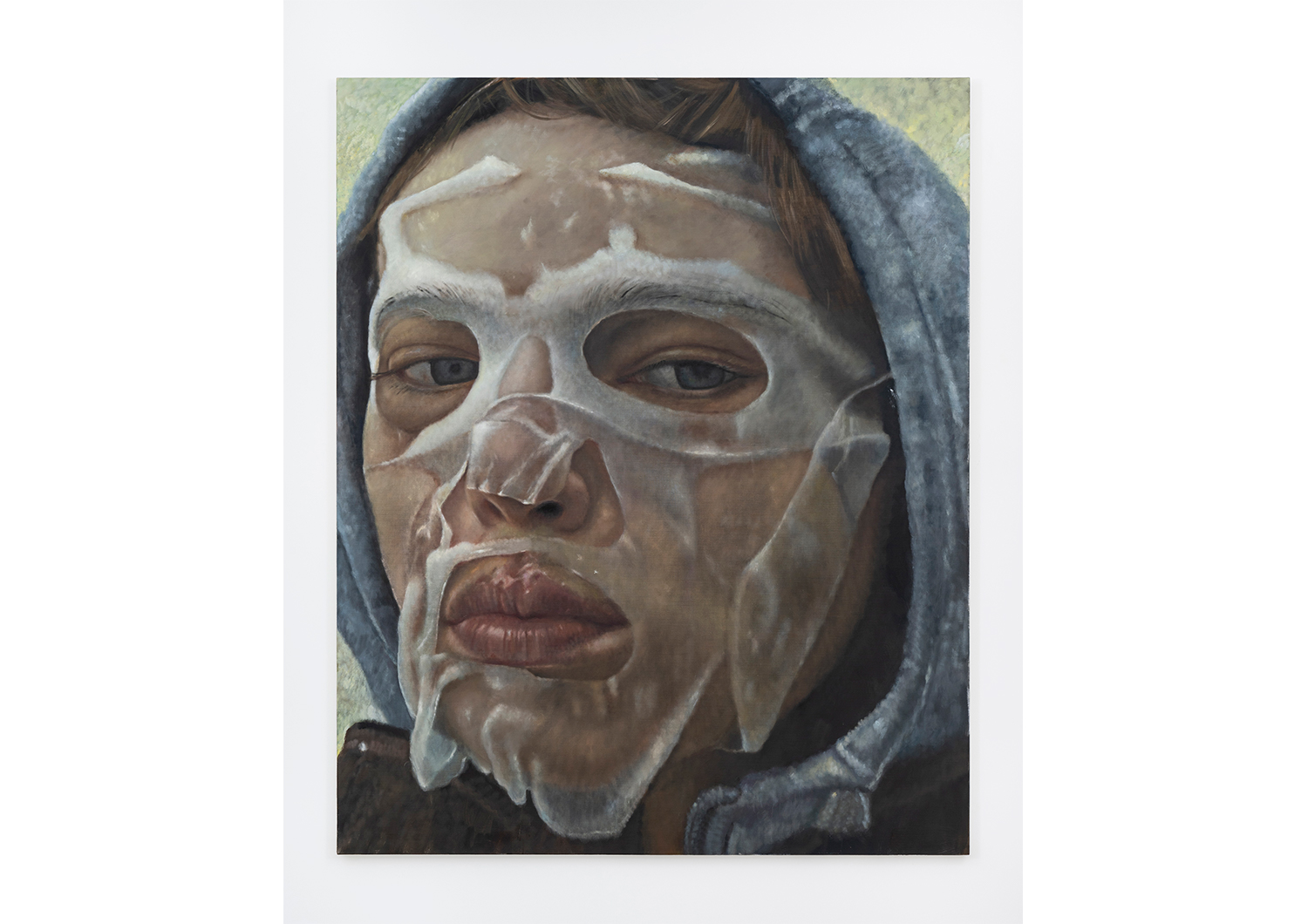

The artist’s midday preservation of dominion takes all sorts of desirous, corroding shapes: gold and mercury nubs, self-portraits popping Lamotrigine, shrunken voices, reading glasses askew, Korean rice-milk facemasks, teethy blowjobs under presidents’ desks, Dear Diary’s, and the quilted padding of emotional armor. Sleep-walking in an NRA cap (and semi-loving it) along the Upper East Side to Michael Werner Gallery’s waxed parquet floors and French doors with gold knobs, Wood waxes lyrical about her mom, who sacrificed her surname for a man, in Mother’s maiden name (2022). Sacrificing in the name of compromise is nonsense Wood hasn’t much time for, and, in patent disregard, she oils up linen with impatient athleticism, rendering an armored silverfish chest vest. A sizeable painting (142 by 182 cm) of a cropped torso in a sacred breastplate, protecting from injurious slays and shrapnel of the frigid patriarchy and familial past: nobody maims and mutilates us like our mothers. In a tightly controlled frame, the armor blocks arrows and tears in a roundabout damehood, fending off epigenetic liabilities passed down by corrupt, sacrosanct powers generation after generation. Here, in an adroit chronology, Issy Wood returns to her mother, her Other, measuring her feelings of guiltless defenestration against her six pop-infused albums: The Blame (2019), The Blame, Pt. 2 (2020), The Blame, Pt. 3 (2020), Cries Real Tears! (2020 [phoar, busy that year]), If It’s Any Constellation (2021 [less productive year]), My Body Your Choice (2022).

Blaming your mother is all the rage

Sylvia Plath had nothing on Issy Wood, whose 254 remastered online diary entries at oldgooddays.net delve into a mind expunging and purging in a less life-threatening, hella witty way. Brava. She’s a frenzied scribbler who won’t — or can’t — hold back, a freckle-dusted Narnian lion writing unabridged versions of preemptive revenge, full of bad will and bestial, insecure attachments. The grunt work of self-portraits and journal entries is something she does with maximum esprit de corps. In a failing exorcism, holy water burning flesh, Wood treads carelessly over political correctness, vomiting Bataillean lies and secretions:

“M arrives and T leaves. We smoke and talk about pedophiles.”

V is in the hospital for a gallbladder infection after a night of excruciating pain and vomiting. On the phone she sounds surprisingly peaceful, medicated. She says she knows I wouldn’t approve of her seeking out private treatment covered by an insurance giant, staunch advocate for the NHS that I am… I tell V I’m just happy she’s comfortable, and that she seems to get an infection or virus of some kind that puts her in the hospital every year or so. “But at least it’s small things,” she says, sleepily, “I mean, except the time I had cancer.”

Maniacal journal entries tread irresponsibly into her first solo show in France, “Study for No” at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris (2023). Wood disregards political correctness in her artwork as a defense mechanism (working title), revealing herself while simultaneously pushing people away. She’s a sensitive artist exploring insensitive issues. An acerbic, truth-telling Pinocchio plays Russian roulette with a fully loaded handgun, veritably impressed by the NHS. Figurative paintings take diaristic form throughout the gallery, a sequence swinging from breaking vines, exploring the collapses of interiority, desire, resentment, vulnerability, and variability. Old and new large-scale works are blown up in near, examining frames, so there are visual details on the periphery that we’re constantly missing, detaching the viewer from the story in its entirety. Up close and impersonal. Can you know an artist through the spews of shakable conviction, enlargement, and shape-shifting mediums? Impossible. She never truly shows up. That being so, Wood’s learned to hold fast to nothing; everything slips through her fingers, algal oils, drinking problems, flamingos, dollhouse bone china, ghostly velvets, rotting crab meat, leather car seats, the asceticism of journaling, butter — a pavilion built on faults de la terre: itself, a kind of rigor. It’s a rhythmic stutter, her refusal of serialism and anything else that might touch her, the collusion between art-making and the corporeal that wraps her in foam and material loneliness. She can’t attach to emotion, and she can’t attach to the people around her; stuck between disparate seasons sitting on an em dash because she’s unable to bear the pain of letting go. If there’s a libido at work here, it’s in the pleasure and pain of control. Can artists interdict the flogs of command through little visual swings at compulsion and ownership? Revolt is all about small betrayals. Sometimes the smallest visual details have the most profound and disabling denouement, and sometimes Issy Wood doesn’t know what’s bothering her until she sits down to write and find out. Through force of habit, she perseveres, but when daily interactions are ill at ease, smoked out by jasmine, disaffection, cleverness, blame, political repression, and quicksilver gas, the whole soul is sick. Control painted as impassivity is artificial, suspect, and ultimately corrupt, but it’s also true that there are people out there with the heart of a lion.

Stable or mature versions of surviving exist; there are ways to go on, but she decided against them long ago.