‘Local versus Global’ was a slogan that was much in circulation during the ’90s, notably in countries experiencing the first flush of the onslaught of the new imperialism that goes by the name of globalization. It has also proved to be a critical catchword for a generation of Indian artists who emerged in that decade, providing a modus operandi, whether consciously or not, for reckoning with the new world order into which India had recently been catapulted.

The video projection Global Clones (1998), by Sharmila Samant, is a witty take on the homogenization that follows in the wake of commodity fetishism and the cult of the brand name. In the video loop projected on the ground in a darkened space, eighteen types of women’s footwear chosen from some of the countries that were once traversed by the old Silk Route that linked Asia and Europe are set in motion, that is, the image of each shoe is morphed onto the next and further animated to simulate a walk. The braided babouches and sequined slippers appear to advance and yet remain in the same spot. In a parody of Zeno’s paradox of the impossibility of movement, the shuffling is also an allusion to the handcrafted footwear’s eventual obsolescence in the face of the industrially produced, mass-manufactured imported sportswear now marketed in India, an example of which — a real pair of Nikes — is placed on the edge of the projection. For Samant, the running shoes are “a marker of the universalizing and flattening effect of global corporate culture and its products,” an object that will get locally ‘cloned’ or counterfeited in its turn.

If many of Samant’s activities are acts of resistance to what might be called ‘commodity conditioning,’ Subodh Gupta’s work, in contrast, has mined the object-world of small town and rural India to explore a dynamic of cultural dislocation. His ingenuity lies in transposing the everyday into the currency of art. The kitchen utensils in gleaming stainless steel that have become a signature element in his work are not only objects with a specific use value; in villages, where they often form part of the bridal dowry, the cups and tumblers and plates have an exchange value, too. By inserting these objects in a non-utilitarian context, Gupta would appear to be playing with the commodity as sign, except that the fetishism thus implied is internally riven by the culturally coded nature of the goods in question. The shiny replicas are, by the same token, the symbolic residues of the functionality of the ‘original objects.’ And since these objects’ raison d’être is utilitarian (their meaning is their use), what is at stake here is not quite the celebration of the commodity in the manner of a Jeff Koons, or a critique of it in the manner of a Sherrie Levine. The singularity of Gupta’s work resides in the unabashed nourishment it derives from the memory of a sense of locatedness, however much he himself has (geographically) moved away from the place of his origins.

The trajectory between the small provincial town in Bihar where Gupta was born and the capital to which he moved has proved to be an energizing resource for his art. Jitish Kallat’s work, on the other hand, registers a quintessential metropolitan experience, proposing a street-level view of the megalopolis that Bombay has now become. Not the city of Bollywood and its tawdry fantasies, but rather the distressed, scarred, grafitti-ridden, monsoon-stained façades of built space, of which the scrofulous surface of his paintings is the analogue. Kallat’s work, whatever the nature of the medium, has always been in scare quotes, and nowhere more pointedly than in Onomatopoeia/The Scar Park (2005). At first sight the set of 68 photographs, displayed in serried ranks in a gridlike structure, appears to be a series of pictorial abstractions, each ‘unit’ distinguished by the particular quality of its surface markings. On closer inspection, however, these ‘painterly incidents’ reveal themselves to be the rather more ambiguous traces of accidents that owe nothing to the play of the brush. These are the scars that attest to a brush with danger, the dents on the gleaming surfaces of cars. So Kallat gives a strange twist to the topos of the crashed automobile in contemporary art (John Chamberlain, César) but in the context of the newly rich and empowered Indian middle classes and their penchant for luxury commodities of all kinds, including the craze for foreign cars: the dents on the bodies of cars registered by the deceptively seductive surfaces of his photographs could be seen as constituting a parodic inventory where social difference is inscribed not as a brand name but as a scar. The danger that seams its way through the urban fabric is also the motif of the three-dimensional work called Petrum Opus (2006): a near-amorphous mass of vehicles precipitously come to a halt on an unfinished highway. Transforming the city into a vast construction site, such overpasses or highways are, of course, ubiquitous in Bombay. That they also signal a potential state of entropy is heightened by the very nature of the material deployed: the translucid resin in which the wax sculpture (of melted vehicles) has been cast preserves as if in amber an indeterminate heap of petrified matter.

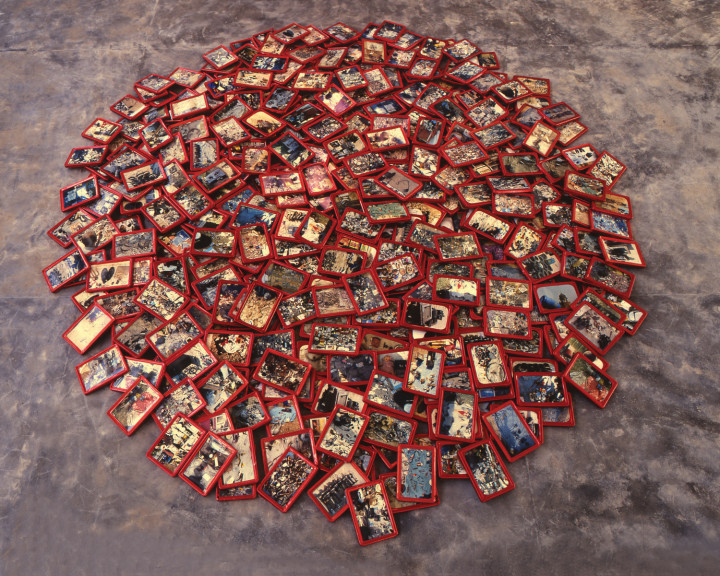

Another perspective on the reality of street life in India is proposed by Vivan Sundaram in the installation he calls Great Indian Bazaar (1997). Alluding to the makeshift Sunday markets that mushroom on the pavements of Delhi, the work consists of 400 postcard-sized photographs heaped on the floor in a circle, a placement that is analogous to the ground level at which the desultory commerce on the street takes place. Indeed, the photographs taken by the artist are of the most disparate objects and bric-a-brac purveyed by the vendors, a plethora that is a ragbag of discards and secondhand goods. For the markets in question are neither an oriental bazaar with its ‘exotic’ wares nor a flea market holding out the promise of a lucky find to the scavenging aesthete, but rather a succession of makeshift spaces rudimentarily demarcated by the plastic sheets on which are accumulated the things that nobody wants to keep. “Used objects carry their personal histories, the quixotic juxtapositions can be read as surreal collages,” Sundaram has observed. “In the moment of examining/photographing the temporary shop on ground level, the hands or feet of the seller and buyer appear at the edge of the frame. By not including the full figure in the frame, your eye focuses on an old shoe, comb, toothbrush, underwear, computer chips, sewing machine. It focuses on reality at the poverty level of ‘consumption.’” This last remark underscores the critical framework in which Sundaram has conceived his installation, just as the real metallic red frames that he found in the market jumble as opposed to isolate the individual images: the viewer is invited to sift through the pile in the manner of the marginals and outcasts attempting to salvage what they can from the detritus.

Sheela Gowda is another artist interested in critically recoding used materials or substances with a vernacular connotation; but her recycling (in the ecological sense of the word) has a rather more pointed moral inflection than, say, Subodh Gupta’s intuitive play with cultural signs. The raw materials to which she is drawn bespeak the harsher realities of manual toil and labor: witness the imposing structure called A Blanket and the Sky (2004) made out of flattened tar drums, a transposition of the kind of improvised makeshift shelters fabricated by migrant laborers hired on a daily basis to lay cables or maintain public works. The austerity of Gowda’s sculptural object avers a ‘truth to materials’ that has an ethical basis far removed from the purely formal understanding of that venerable modernist shibboleth. Indeed, the monumentalizing of the modest dimensions of the shacks is a paradoxical way of commemorating their own precariousness as well as that of those for whom they provide a roof for the night. Gowda’s preference for poor materials reflects on her engagement with environmental issues and so-called women’s work. From the standpoint of these preoccupations, the recycling also amounts to a critical recoding of whatever formal associations with post-minimalism or Arte Povera. Thus, such elements as string, pigment, charcoal powder and gauze — that go into the making of the work called Breaths (2003) — have a symbolic valence that is necessarily different from the recourse to comparably modest materials that register Arte Povera’s resistance to the technocratic basis of minimalism. So the truncated limb-like forms smeared with charcoal and tipped by blood-red pigment and placed on a long narrow table could well be called ‘still life,’ although that generic title would resonate differently for someone aware of the massacre of Muslims that took place in Gujarat in 2002, and in whose aftermath this work was made.

The idea that contemporary life might be approached as a fable has long exercised N.S. Harsha’s pictorial imagination. Often panoramic in format but miniaturized in its delineation, his paintings are both expansive and intimate, and maintain a continuous and lively interplay between the detail and the whole. The myriad vignettes drawn from everyday life are presented as an extended frieze, as a succession of superposed horizontal lines rather in the way sentences follow each other on a page. This allows for an overall structure and for a play of repetition and difference. The multitudes that people his paintings are particularized by the minutiae, by their wayward and quirky details. Those familiar with the stories of R.K. Narayan set in an imaginary small town in south India will see in Harsha’s paintings the work of a kindred spirit. Like Narayan, Harsha casts a bemused, affable gaze at humanity and its foibles. He is interested in the circulation of cultural markers or signs, and the manner in which these are interpellated, especially in the context of the globalized present: villagers posing for a photograph with the leaning tower of Pisa as painted backdrop (Mass Marriages, 2003) a peasant crossing a river and carrying on his head not the usual bundle of cloth but… Duchamp’s urinal !(We Come, We Eat, We Sleep, 1999-2001). These are details and of course they gain in wit when seen as part of the larger configuration of the paintings in question. The playful re-routing of cross-cultural references informs the sociability of Harsha’s world. In R.K. Narayan’s short stories, “a pattern of existence is brought to view”; in Harsha’s paintings, for all their endearing formal qualities, that pattern does not exclude the motifs alluding to the drudgery that life is for the less privileged. A recent painting, Creation of Gods (2007), shows serried ranks of small-time tailors working on the same swathe of black cloth as it winds itself from one sewing machine to the next. In all likelihood, this is outsourced labor paid at a pittance. Is that why their faces are spectral, or that the planets and comets and shooting stars festooned on the black cloth might appear unreal to them? To raise the question is also to acknowledge the delicacy of Harsha’s way of posing it.