There is no sign of an end to media penetration in our lives: the victorious progress continues. So, thanks to MySpace and YouTube, the Internet has established itself once and for all as a medium for moving pictures. And additionally as a public medium that seems to make ‘non-hierarchical’ and ‘participative’ presentation possible. But the old new media, such as TV, for example, are constantly and powerfully broadening their scope, so that TV consumption has continued to increase recently, by a full 25% in the last 10 years in Germany for example!

This has already had absurd consequences: to choose an apparently harmless example, the athletes at the Olympic Games in China didn’t start at the best time for their sporting performance, but at the prime time for advertising income on American television. Here reality is formatted by the media, the rules of the image dominate what is depicted, rather than representing it ‘faithfully.’ And in the meantime radio, once seen by Bertolt Brecht as an emancipatory “education apparatus,” has for a long time now been nothing but a light entertainment medium, though an extremely pop-led and popular one. Today’s young artists, who have of course grown up with this ‘media overkill’ as the MTV Generation, reflect these developments in a wide range of very different ways. The common denominator here seems to be a tension between fascination with, indeed affection for, the many possibilities afforded by the media, and contempt for its dumbed down, uniformly ruthless commercialism.

One good example of this is BjØrn Melhus’s work. His video installations constantly shed playful and yet critical light on various TV genres. BjØrn Melhus slips enthusiastically into various roles in order to do this, taking the presenter, the show dancer, the talk show guest, etc., and then using his “tele-egos” (Melhus) to reflect critically on the media, both by identifying with and parodying them. His most recent video installation Deadly Storms (2008), for example, works in this way. News by the American media giant Fox is presented here, or more precisely, the artist directs a critical spotlight on its Republican bias and political coloring. To do this he imitates the program’s computer-generated, apparently progressive corporate design, and then takes the role of newsreader as a ‘live talking machine’ (Melhus), reciting a collage of original fragments from the program that show how Fox constantly uses alarming, sensational news items to work towards a “shock doctrine” (Naomi Klein) that then creates a political climate in which democracy seems to be threatened and needs to be rescued by abolishing various human rights. As early as 1985, Neil Postman had written that politics was threatening to degenerate into a media spectacle, in his book Amusing Ourselves to Death. Like Melhus, Francesco Vezzoli also takes this as his theme in his video installation Democrazy (2007). Two separate election campaign films are presented: Patrick Hill and Patricia Hill compete for the job of president of the United States. Significantly, Patricia Hill is played by the Hollywood star Sharon Stone, and Patrick Hill by the French philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy, effectively as a representative of the old Europe. However, the two are presented almost as one, talking meaninglessly but emphatically about peace, kissing children, celebrating the American dream… It is almost impossible to make out any differences in their programs; a dazzling smile is made into an argument, a successful bit of film editing stands for conviction. So, and this is no coincidence, Vezzoli succeeds in creating parallels with the current election campaign in the USA — and in sketching out a gloomy prognosis of what is increasingly becoming (media) reality in other Western democracies as well. Incidentally: both BjØrn Melhus’s and Francesco Vezzoli’s works can be seen on the Internet, on YouTube.

The American artist Michael Mandiberg also relies on the Internet as a medium, for example, the Internet Mandiberg Shop, which sells items owned by the artist. Through his site (Mandiberg.com) the artist logically focuses this principle of acquisition on works of art, for example on Sherrie Levine’s series of photographs “After Walker Evans,” which Mandiberg posted on the Internet as free downloads at AfterSherrieLevine.com. So unlike traditional online art auction houses, Mandiberg continually exploits the opportunities the Internet offers to art (acquisition). As well as offering non-hierarchical access to all, and free access as well, both the artist and his medium negate any claim to authorship and originality. Instead, an unrequested genealogy of networked users becomes part of the aesthetic master plan. The chain extends from Evans to Levine, and from there to Mandiberg himself, and finally on to the art lover who downloads the image. Particularly in this work, the tension between fascination and contempt is clearly present, as Mandiberg appears fascinated by the opportunities the Internet gives for emancipation and freedom, but also clearly sets himself apart from the profit-oriented uses of this medium that exist, as demonstrated by auction houses, for example.

Candice Breitz bases her art on a dialectic of media consumption and her own production, however sees this as an entirely distorted relationship in which the media user’s own formulation scarcely goes beyond a copy of what is provided. This becomes clear, for example, in her installation King (A Portrait of Michael Jackson) (2005): fans of the king of pop can be seen on 16 monitors, singing songs from the Thriller album, all of them dancing and gesticulating… These performances are placed somewhere between a copy of Jackson and a ‘personal’ interpretation; common factors and differences are revealed in the serial display of 16 variations, an almost scientific and objective approach. This ‘portrait’ presents a picture of Michael Jackson and a picture of the fans. But the latter shows the 16 protagonists as subjects who are not self-determined, but acting as clones of the media star, like parrots. However, we could suggest that Candice Breitz gives these people at least a limited chance to introduce themselves into the media game that is pop culture — different from MTV, where the fans usually appear as simply screaming teenagers.

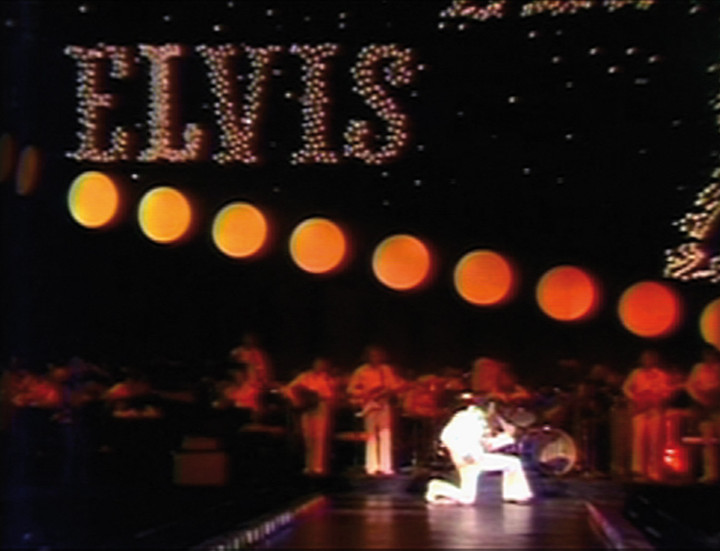

The American artist Jonathan Horowitz treats the great names of rock and pop music in a quite different way. Take his video Elvis ’58/’93 (2007), in which Horowitz creates a parallel between the story of “Elvis the King of Rock’n’Roll” and the soldier Clifton “Elvis” Wolcott. Clifton “Elvis” Wolcott’s deployment in the Mogadishu campaign in Somalia in 1993 was filmed, as is well known, in the 2002 blockbuster Black Hawk Down. Jonathan Horowitz now collages excerpts from this war-glorifying film from Hollywood, the alleged dream factory but actually a dumbing-down machine, with photographs of Elvis Presley as a rebellious rock musician at the start of his career — appearing as the brave soldier serving the state and finally as an actor-musician featured in the war film G.I. Blues (1960). The glamour of the rock star and that of war worked up by the media thus enter into a dialogue that pillories both the aestheticization of the most terrible phenomena and the instrumentalization of rebellion during this process. The latter also stands as a paradigm for the fate of any protest that threatens to disrupt the affirmative media machines.

The Berlin-based artist Christine Würmell also uses a bundle of media in her works Global Player and Bollocks was it the Hand of God (2006). Firstly, Würmell threw balloons filled with blue paint at the wall of the exhibition space; the balloons consequently burst and paint ran down the wall. This practice of throwing paint bombs is a medium that is commonly used by left-wing activists, but it can also be seen as a piece of action painting. In this way, Würmell equates the act of protest with the act of art. The same is true in a calendar published by the Swiss art magazine Kunst-Bulletin, listing all the major art events for the year, accompanied by forthcoming activist events — both artists and activists have long been ‘global players.’ This calendar hangs in the middle of the paint bomb, in a white frame. The blue-and-white coloring of this thrown wall picture also alludes to another ‘global player,’ the Argentine footballer Diego Maradona, who is central to the second part of the work. For example, in this pictorial ensemble, his tattoo — again a medium of the sub-culture — can be seen on his upper arm with a likeness of “Che.” Maradona also appears in a photograph with Fidel Castro: the two men are taking part in a chat show on Italian TV, and as a result Maradona comes to stand for the dialectic of protest and affirmation, which can also be found in Horowitz’s Elvis: the football star is both a left-wing activist and a commodity worth millions, who was traded at high prices in the international sport and media market. So taken together, the two parts of the installation produce a complex tissue of global pictorial information, offering contradictory but explosive reflections on globalization and resistance.

The British neo-conceptual artist Jonathan Monk is also fascinated by media images — though only by those he has distorted: they develop a fascination as constructions that have been led astray. Monk deliberately undermines the normative and conventional logic of media images by deliberately building errors into them. One striking example of this is his series of work called “Little Things Make All the Difference” (1999), which consists of press photographs of gripping scenes from football matches. However, Monk has surreptitiously cut the football out and placed it somewhere else in the image; his action is almost unnoticeable. The goalkeeper suddenly jumps into an empty space or the striker jumps for a header even though the ball is at his feet…

Deleuze and Guattari have already pointed out that “desiring machines run only if they are not functioning properly.” Monk’s work functions precisely like this: he immediately succeeds in deriving surprising dimensions from the standardized aesthetic of the press. There is something in this work that applies to all the works discussed above: we have said goodbye to the lack of inhibition and optimism with which most young artists once used the media, even in the ’90s — two examples: Pipilotti Rist and Jeffrey Shaw, both of them naïve in very different ways. Today skepticism and protest set the tone.