Over the past decade, much has been written about the rise of performance in contemporary art’s institutions, with gargantuan architectures like Tate Modern’s Tanks or New York’s The Shed now inviting a wide range of artists invested in event-based work. This trend in performance programming (and dedicated editorials of this sort) is often associated with the museum’s recognition of consumer appetites within an experience economy. But while a healthy sense of skepticism of this commercialization is worth maintaining (particularly if, in return, it neglects to attend to the infrastructures, services, and wages required to support events fairly), what begs consideration is how the specific qualities of performance — and the unique facility of dance — is able to spotlight the grip of the attention economy, of which the single greatest unit of currency is the digital image in circulation. And whether or not it’s intentional, the development or appropriation of cavernous, modular, and interlinked spaces for performance allows for a theater of images and a choreography of circulation fit for the times.

The image and the specter of the camera are everywhere, on every street corner and social gathering, on every interface, media platform, and blog. They transition between spheres in our hands through applications on our phones. There are many political consequences to changes in media, from centralized and regulated distribution models to underregulated, prosumer-driven circulation: streams and perspectives of reportage multiply, witnessing and evidence changes, hegemonic accounts are potentially challenged. Recent paradigm shifts brought about by MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and Extinction Rebellion validate some of social media’s claims about providing connectivity. But the adverse ramifications are many: habitual social media usage increases dependencies on information consumption and production; and frequent engagement creates data, extracted and fed back as targeted content, a process corporatizing our decision-making such that commonly used platforms have taken physical and psychic possession of spaces formerly, if problematically, considered public. All this “sharing” of content is mediated by companies holding hands with other companies holding hands with politicians — alliances fostering covert and unregulated campaigns, such as is evident in the recent Cambridge Analytica investigations.

Performance has long been a medium accommodating and permutating different forms of protest. Whereas once a key site of public demonstration was in the street — a realm into which performance art inserted itself wholly as a critical corollary to public demonstration — spaces of public demonstrations are now changing, occupying both public and online spaces where images and captions circulate. Images on platforms become nodal points for positive identification and congregation, as well as for the aggregation of political groups on both the left and right. It is also a site of apathy: where evidence and editorials on all manner of catastrophe are willfully ignored in favor of GIFs and jokes. To visit social media is to accept the brutality of apathy as a consequence of selectivity. Thinkers across fields grapple with how to contend with the power spectrums of the circulating image facilitated by platforms that implement technological updates considerably faster than they mandate corresponding ethical or judicial frameworks. The task of understanding the politics of the image and reforming its platforms is upon us all, and few fields of practice seem better equipped to do this as openly as those of visual art. And within this field, and toward this task, performance flourishes.

In London, on a rooftop parking lot, a crowd gathered at dusk. By May 2017, Boris Charmatz’s Danse de nuit had been performed several times, but I still prickled with fear to feel a shove against my heel and look down to see Charmatz on the ground, rolling against my leg. I tripped. Around me appeared further intimidations by five other dancers, each wearing varying styles of streetwear. Sequences of street dance and contact improvisation moving across the large space were punctuated by dancers’ vocal projections. “Charb is dead. Charb is dead. Charb is dead,” they harmonized at volume on the murder of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonist, Stéphane Charbonnier, in Paris in 2015. Between refrains, Charmatz’s six kept in constant contact with the crowd, sometimes through head-on confrontation, other times through more subtle directives. The action surrounded us, and keeping track of it demanded constant pivoting and scanning. To disorientate further, four other dancers carried panels of searing light on their back, strapped on like oversize rucksacks. Designed by Yves Godin, the beaming four counteracted the dancing six: where the dancers divided the crowd, the carriers fenced us back in, their opposing waves dispersing us around the space.

“Danse de nuit was born from a sense of anxiety, but I think there is also a desire for public space. People want to come together,” said Charmatz in 2017. “I wanted to create a choreographic assembly, to see what could be done in what is currently a space of fear.”1 Tapping into these familiar currents, Charmatz also acknowledged the role of the image in conceptions and configurations of public space, where image capturing and sharing plays a key role in both the public and the media’s response to unexpected events. Late in the performance, a dancer recites Tim Etchells’s video poem Starfucker (2001): “Tom Cruise on an operating table. Susan Sarandon’s head in a bucket. Johnny Depp in a deep freeze.” The spectacle of the abject creeps and lodges in memory, uninvited but disarmingly easy to recall. Images-in-circulation present some of the most incendiary information bites of our time, with real-time implications on our behavior and interactions on the ground, inducing hatred, terror and, unrest. Charmatz’s work recognizes this complicity between image and action (or inaction), but it asks more of us, of our musculature — it pushes us to transfer fear into a different form of readiness, for a kind of cooperation or accord. Dance requires flat urban space to work, and Sadler’s Well’s adoption of the parking structure accommodated Charmatz’s experiment quite perfectly.

Working from the image, or combinations of images, has been pursued as a choreographic strategy since major shifts in North American “postmodern” dance and associated experiments in performance from the early 1960s, with artists learning directly from instructors of Bauhaus’s pedagogy of stage studies. And while this compositional strategy is now by no means exceptional, conceptualizing pieces and instructing dancers through images set against unconventional non-proscenium stages seems to resonate for art or museum audiences, specialized and non-specialized, in rapidly changing political economies of images. Arranging human movement dynamically as one might organize images in circulation, in sequences or tableaux, in transitions or jumps, in montage or collage, provides a different way of “watching” the image (to borrow Ariella Azoulay’s phrase), an oblique angle from which to access or approach it, to better scrutinize its object and the platforms upon which it is made to travel.2 On broad stages, the trick shots are no longer in our hand. While the artists in this article conceptualize through imagery for various reasons and with different effect, none of which include maintaining or contributing to the idiom of “post-internet,” their practices elicit a deep sense of concentration on the politics and circulatory mechanisms of the image, historically and contemporaneously, putting the operations of images in sharper relief.

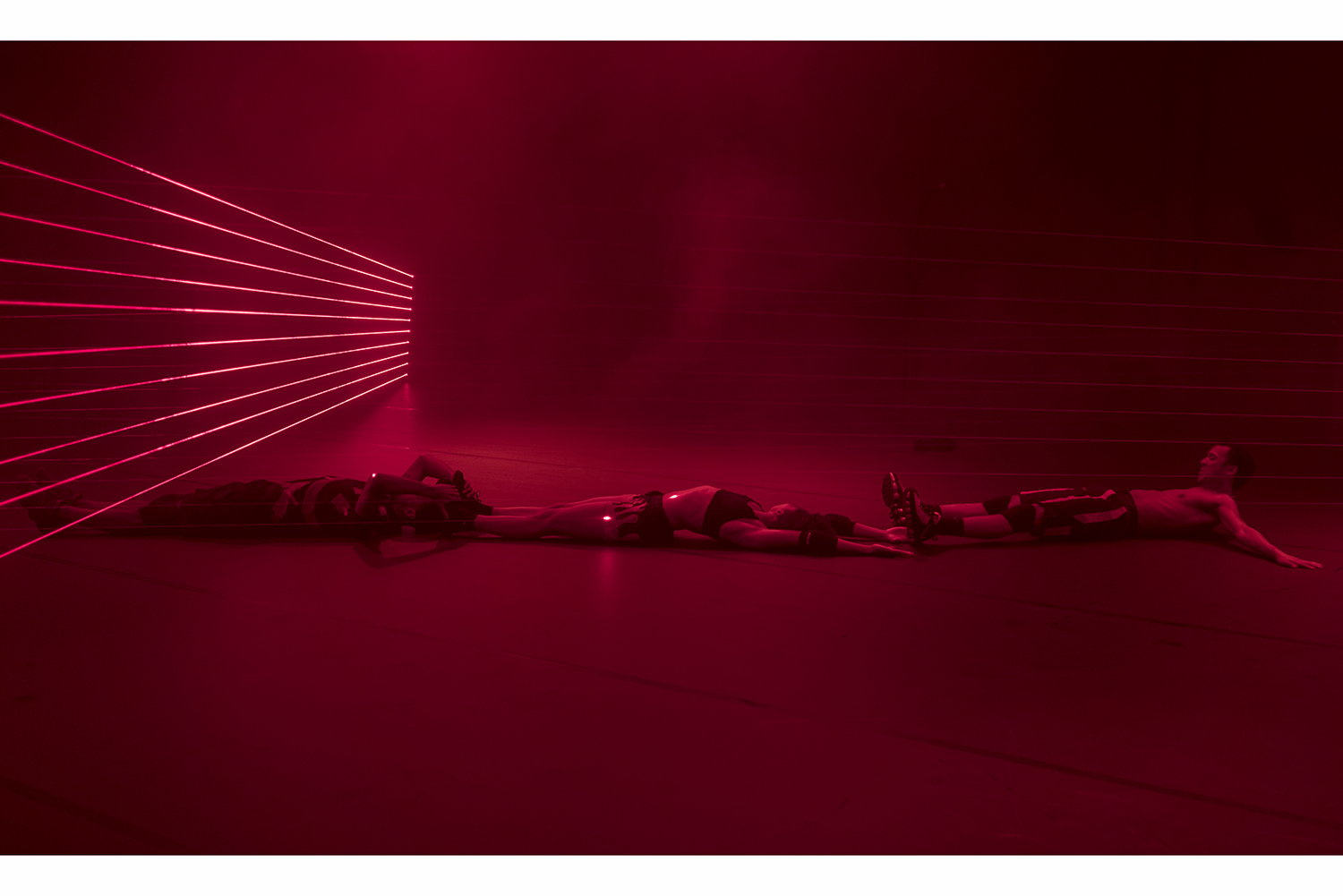

“In my work, I often start with something more obscure, like an image or a sound, or a sense of movement,” says Ligia Lewis of her choreographic approach. “Maybe later I’ll invite texts into my process as a way to elaborate further on what I’m intuiting.”3 The atmospheric lighting in her trilogy Sorrow Swag (2015), minor matter (2016), and Water Will (A Melody) (2019) is schemed according to the blue, red, and white of the American flag, respectively, but the works are less a decoration of a nation than a multipronged research approach toward a holistic “antagonism toward white supremacist logics — the logics of empire — and their hold on the body.”4 In minor matter, Lewis performs alongside two other dancers (most frequently Corey Scott-Gilbert and keyon gaskin), where the trio unify and split, entangle and line out, to Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607), Ravel’s Boléro (1928), its remix by Moritz von Oswald and Carl Craig (2008), and later Donna Summer’s I Feel Love. Lewis adapts Maurice Béjart’s Boléro (1960) and later includes elements of African dance vernaculars, step and gumboot, the latter’s exaggerated footwork originally a codified form of communication between workers. The trio moves through various performative tableaux and different configurations of solidarity in what Lewis calls “a logic of interdependence.”5 In concluding sequences, Lewis and her co-performers climb and fall against the limits of the stage’s black box.

Lighting sweeps throughout the performance, blanketing dancers, pulsing to the music, and intensifying an already engrossing viewing experience. As the stage’s outer limits continually resist the black dancers’ advances, the viewing exhilaration turns foul: this is how viciously whiteness contains black subjects. Lewis choreographs “sideways,” she says, long concerned by how, in thinking around the image, she might “problematize particular kinds of visibility, and challenge what’s legible to hegemony.”6 White hegemony’s grip on the sphere of who and what is visible remains little thwarted despite big tech’s claims of democratized platform provisions, so the persistent question in Lewis’s work is how whiteness, this white us, must recognize and challenge our complicity before we are to achieve any real solidarity.

The politics of visibility are also approached obliquely in the work of Northern Irish choreographer and dancer Oona Doherty. A recent work, Hard to Be Soft: A Belfast Prayer (2017), is in part tribute to the city where she grew up and in part a story of how its internal tensions both informed and liberated her movement, combining elements of ballet, dance theater, street dance, and “instinctive performance” (after Guilherme Miotto). Belfast is the capital of Northern Ireland, a state that experienced three decades of civil war from 1969 to 1998, commonly referred to as “the Troubles.” It has long contended with reductive, spectacularizing, or polarizing imagery circulated in British, European, and US media during and since this period. Images of working-class communities in conflict have become a common trope, obscuring broader analysis of systemic injustices caused by British state and military interventions, resulting in an ongoing situation in the UK of ambivalence and inaction still evident in today’s Brexit negotiations. Doherty’s piece expands from previous work exploring the communicative posturing of juvenile hetero-masculinity across Europe (Hope Hunt & The Ascension into Lazarus, 2016), with this newer work examining how masculinity has been set against itself among the disaffected Catholic communities of her youth.

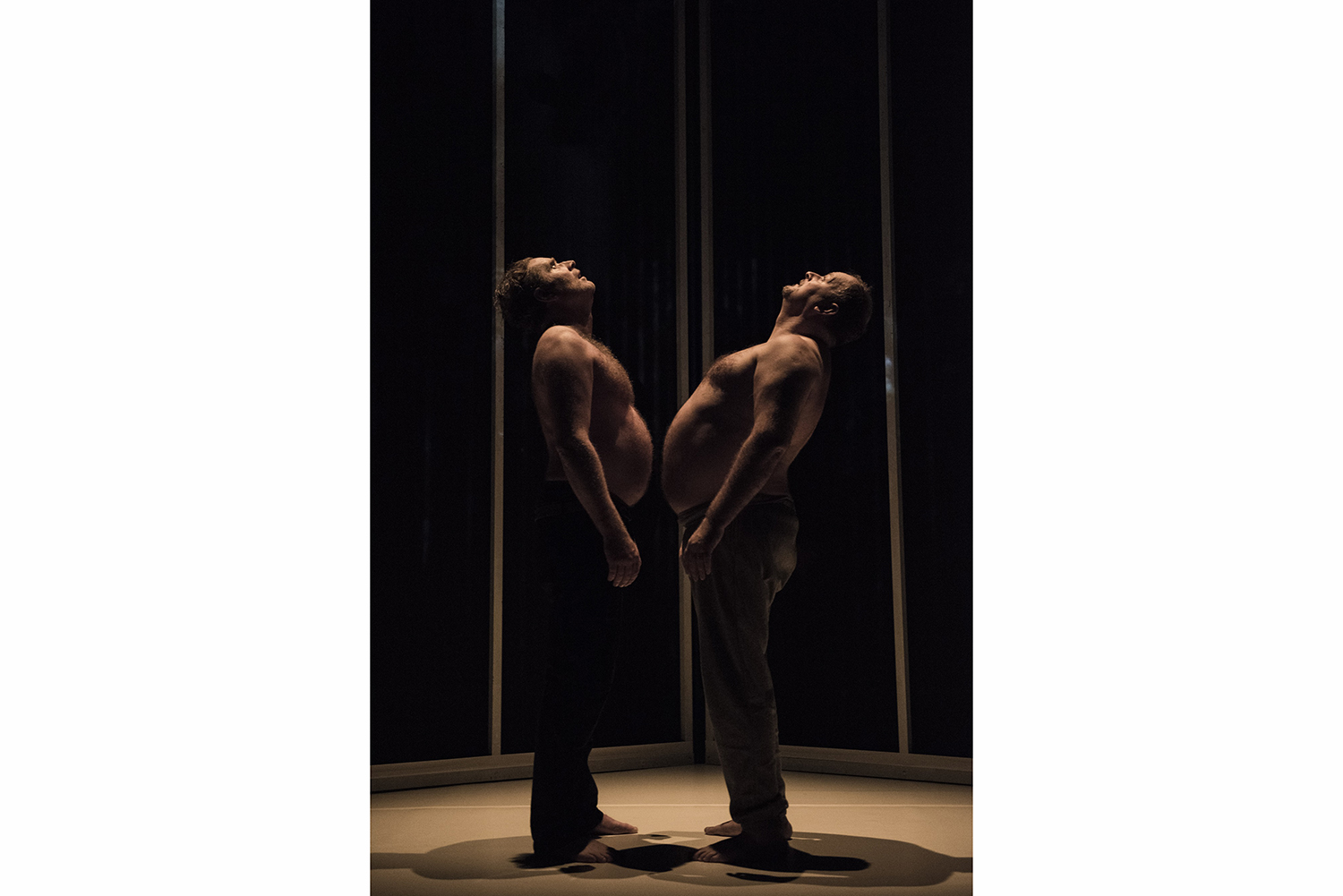

Doherty’s piece is composed of four episodes: the first and last she dances solo; the second, Sugar Army, is a group hip-hop dance performed by ten female teens in which Doherty draws on her own teen experiences; and the third, Meat Kaleidoscope, sees two overweight white men approach one another, spar, and reconcile (an imagined version of her own family’s reconciliation). Northern Irish musician David Holmes has designed the sound, and for her solo mixes Allegri’s Miserere mei with intermittent samples of voices from Belfast, recordings of men sermonizing, confronting, gasping, dying, of women screaming in horror. Pitch and tone are elevated, although narrative details remain inaudible, and it is to a frequency rather than a specific event that Doherty’s body moves. She characterizes men young and old so perceptively they seem uncannily close to the surface. Between characterizations she sinks to recline as Lazarus, after whom the first solo is named, a biblical figure resurrected from the dead. She oscillates here between street dance and ballet, working between performative repertoires to break this familiar and destructive trope, this stereotype of infighting in Northern Ireland, codified images used to preserve British hegemony.

I watched Doherty’s piece this autumn at its (long overdue) premiere at London’s Dance Umbrella festival as the “issue” of Northern Ireland brings about a crisis of governance in Westminster threatening the long-term union of Britain’s states. The force of the piece reminded me, as Lewis’s and Charmatz’s did before it, of how invaluable the experience of performance is in a new set of relations between governance and media, making us watch images obliquely and with due caution, on unique, scaled-up platforms, while rethinking forms of sociality, solidarity, and group action.