Matthew Day Jackson: Do you think you are actively creating a unique formal structure for making sculpture, akin to Brancusi, Giacometti, Bourgeois?

Huma Bhabha: I think the artists you’ve mentioned are all a part of a long ancient line of artists/artisans who go beyond a prevailing formalism or any one ideology, who have pushed things beyond the familiar, beyond the comfortable. To me art functions kind of like heartburn warning the world of some unhealthy practice. If the world were healthy it wouldn’t need art.

MDJ: I think you are doing this as well. Don’t you think so?

HB: Yes.

MDJ: Is there a plan as to what these things look like when they are finished?

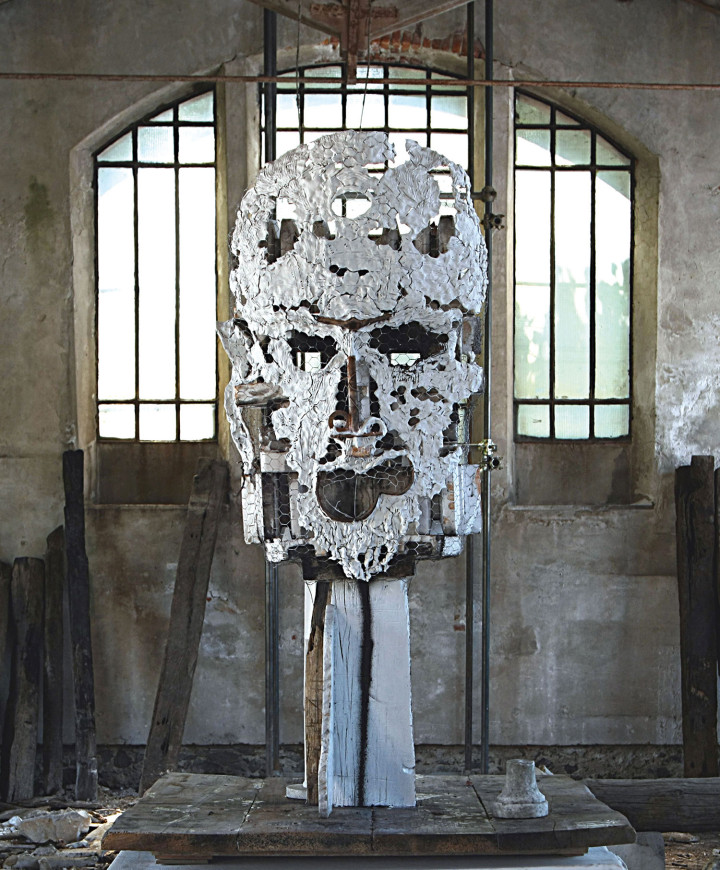

HB: The plan unfolds while I make them, and the first stage is to create a structure that stands up. I only know approximately how big the piece will be when its finished: bust, standing figure, or a more extended tableaux; everything else is extremely organic and fluid, depending on the materials and how they start to fit together.

MDJ: For you, the journey in making sculpture is thinly masked, as the structure and the surface are readily viewable. Are these forms a view of a sort of purgatory — in a state of dying or coming back to life?

HB: All of your observations are happening in different ways and from different views in the sculpture. The alchemy of the materials is placed into spaces that seem dark, cavernous, forging monumental bodies that are evolving and withering at the same time. For me, seeing the chicken wire is like when in Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot Le Fou (1965) Jean-Paul Belmondo turns and talks to the audience. The curtain is drawn and the wizard is revealed as crusty and gnarly chicken wire.

MDJ: Or perhaps like the monks at the end of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain (1973)? In cinema, directing the viewer’s attention to the skeleton that supports the flesh of what they are seeing is anarchistic to the medium. In sculpture, to make one aware of the process is to include the viewer in what I see as a very generative and generous way. Do you even think about the viewer? I don’t.

HB: I think the differences and similarities between viewing a movie or a sculpture are very interesting. The big difference between cinema and sculpture is that in cinema you’re in a dark room, which encourages you to leave your body and enter the cinematic image. Whereas with sculpture you are usually in a bright room and the viewer becomes more aware of their body while encountering a sculpture. But both practices are usually steeped in narrative, which is why Bernini can feel so cinematic, even though it was made before cinema existed.

MDJ: Where does the viewer exist? Or rather, what is the ideal environment for your sculpture?

HB: The Parthenon, inside a giant glass cube designed by I.M. Pei. The viewers would be in helicopters hovering above.

MDJ: It is as if you thought maybe they were alive? Like a caged animal?

HB: More like gargoyles guarding a sacred site waiting for a distant future when they can wake up again, but also like animals in the sense that they cannot speak; in Urdu — Pakistan’s national language — we have a word, bezabaan, which means without tongue.

MDJ: Would bezabaan mean to be without language, or literally without a tongue? Or could it mean both? I like thinking of this, as it seems that this is really the predicament of being an artist. Caught with words to say but without the immediate facility to express them.

HB: I think to me bezabaan refers to both without language and not being able to communicate to those that don’t understand your language. The Robert Bresson movie Au hasard Balthazar (1966) tells the story of a donkey’s life from beginning to end and expresses exactly how I understand bezabaan. In an animalistic sense the artist’s work is the equivalent to the cry or howl (which is the true language of the bezabaan). But does anyone listen? It can only be seen, not heard. One can argue that is how art ultimately functions in the world.

MDJ: I think your work says precisely what you want it to. Or rather, I think that these figures were at one time alive, and that you are revealing them to us. Not by creating them, but rather re-creating them exactly as they were. This is not a project of representation, right?

HB: The work is straightforward; it’s not trying to fool anyone. But in a sense you’re right, I do like the idea of the giants that once walked the earth. Representation is not an issue, it’s more like the materials being revived in a new form; the sculpture parts were all alive in some earlier state, some parts fulfilled a function like being in a car, protecting some packaged electronic equipment; other materials were new (the clay, chicken wire, etc.).

MDJ: I think there is something to the anarchy of art and its life is gauged by how it doesn’t fit in the society it reflects. Your work in particular doesn’t seem to fit in the New York art world. Is this true, and if so does this make you feel lonely?

HB: I’m a lot less lonely than I used to be. And there have always been artists in New York even from when I first came here in the late ’80s that I have felt connected to. But I do think my interest in a certain period of European sculpture represented by artists like Giacometti, Picasso, etc. separates me from the dominant tendency to refer only to Pop and Minimal art.

MDJ: Or using irony as a primary currency in the expression of ideas? Which I see unrepresented in your work. On the opposite side of irony there is humor. Do you see humor in your work? Could it be expressed through scale? Or perhaps a comedy of materials?

HB: Yes, there is a lot of humor in the work, starting with the choice of materials. Used packing foam, old wood, rusty garbage, etc. but when assembled, they cut an interesting figure like Charlie Chaplin’s ‘tramp.’ And I think some of the faces and heads can be quite funny. They don’t just relate to the history of sculpture; there are a lot of hours spent watching horror and sci-fi on television in those heads, and I think that brings some very necessary silliness into the mixture.

MDJ: Although you say there is silliness, I have always taken these figures very seriously. There is a haunting quality to the work, and the way they are made suggests they come from here, but in a state of disrepair in the sense that the materials used are not in the location we would associate with their intended use. When did the apocalypse happen?

HB: The apocalypse has been happening for ages and we are right in the thick of it. That’s why you need humor to create some grotto of relief, otherwise it can get too dark. I like when it can be read either way. Do you think the apocalypse has already happened? Is it one day? Or is it human history? Do you have any inside information?

MDJ: I think that the sun will burn out and our universe will implode. From now until then, our spaceship Earth will see many different manifestations of life and civilization. I fantasize about being there to witness the implosion. In a way, I think we are both trying to see it now, and to report back on what we have seen. The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths. In revealing mystic truths, are you a seer, a medium, or a prognosticator?

HB: The truth is not something you can easily divide into segments or roles, it is more a circuit of information through which the artist views events in the world as they happen, are ignored and then forgotten. And for me that circuit sort of relates to your previous question regarding purgatory — it becomes a sculptural circuit, which contains all of those states, and in that circuit I guess I ultimately operate as a medium. However, I prefer to think of myself as a neutral agent between the areas that interest me: art, politics, cinema, etc., and the materials I work with, but it is impossible to maintain complete neutrality, and so the circuit is somewhat corrupted by personal stuff, which is good as long as I keep it to a minimum. I don’t find myself that interesting. And as Duchamp said, “I would like to be completely — I don’t know what you say — nonexistent.”

MDJ: Three cheers for Duchamp! However, in this world of high-production artworks, one would think that contemporary art had fully achieved this, only by enrolling people who know their hands better than the author of the artwork. You make a very different kind of sculpture. In trying to be nonexistent, do you think the act of making is akin to an act of suicide?

HB: When experiencing Duchamp’s work I always feel his hand. Even with the readymades you can imagine him going to the store and picking up the object and examining it. His work for me is very different from the impersonal, fabricated-in-China work that seems to be everywhere today. I’m interested in a suicide of the self when I make the work: no country, no gender, etc. I don’t want the work to be tied to any one specific self or ideology. When you are nothing, you can become everything.