“We were cultural criminals, media parasites,” writes AA Bronson in the preface to the catalogue accompanying the traveling retrospective of the Canadian collective General Idea, now on view at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Later in the same text, Bronson, one of the group’s founding members, continues, “We were taking orders.” These lines capture the spirit of the collective. By identifying with parasites, criminals, and servants, Bronson aligns the group with transgression, with disobedience, but also establishes a Warholian approach: the artist as machine, carrying out a process in order to reveal something about its structure.

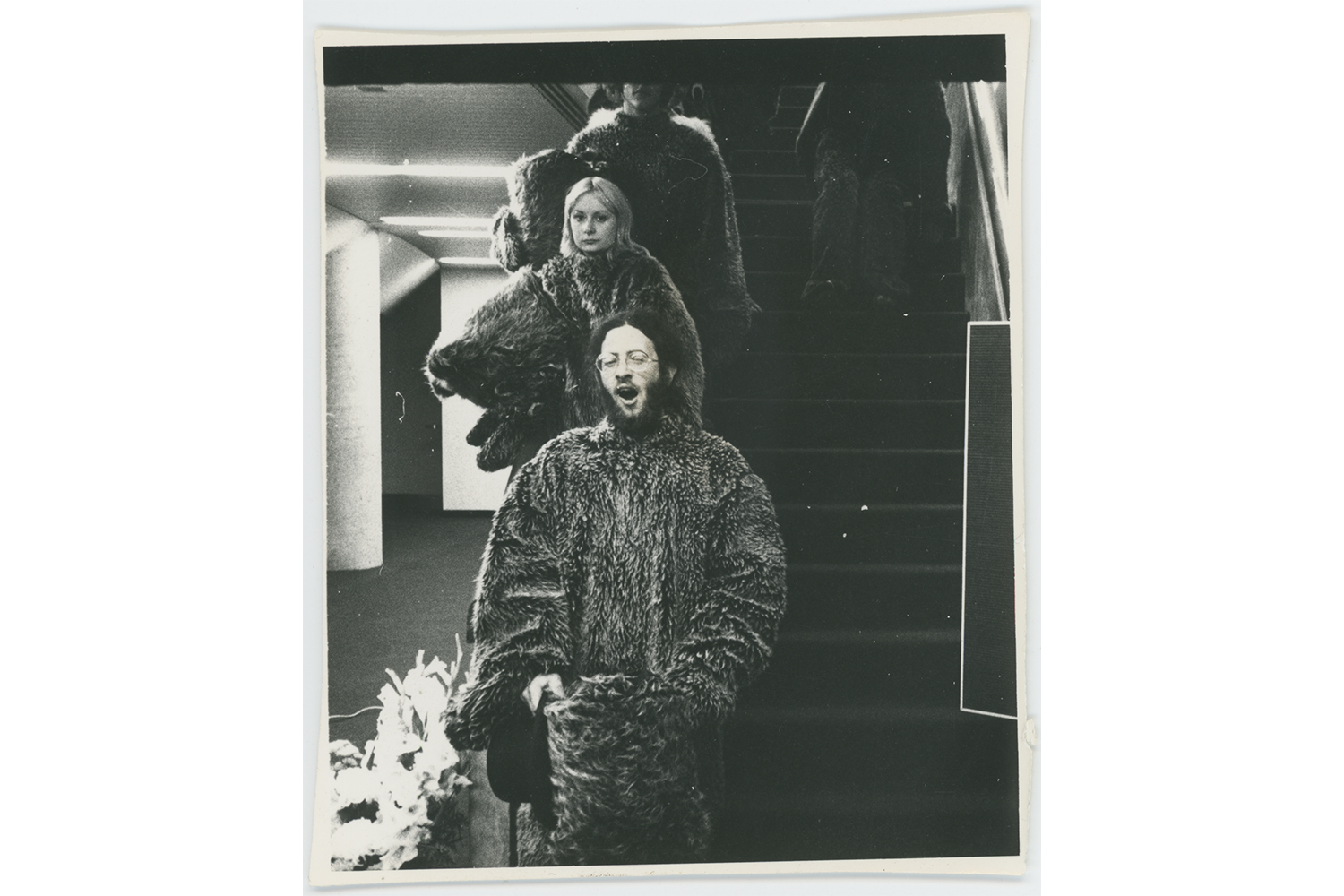

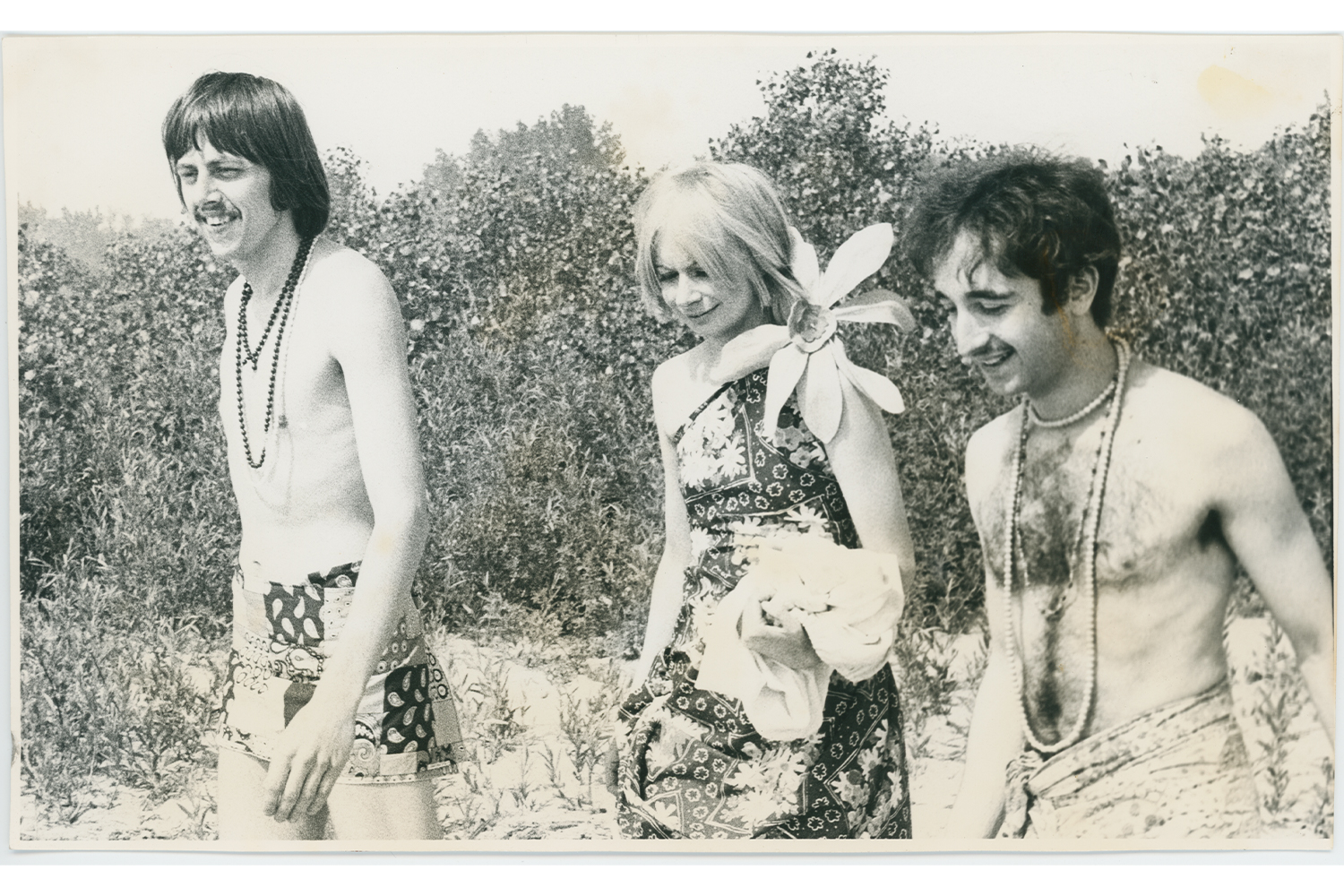

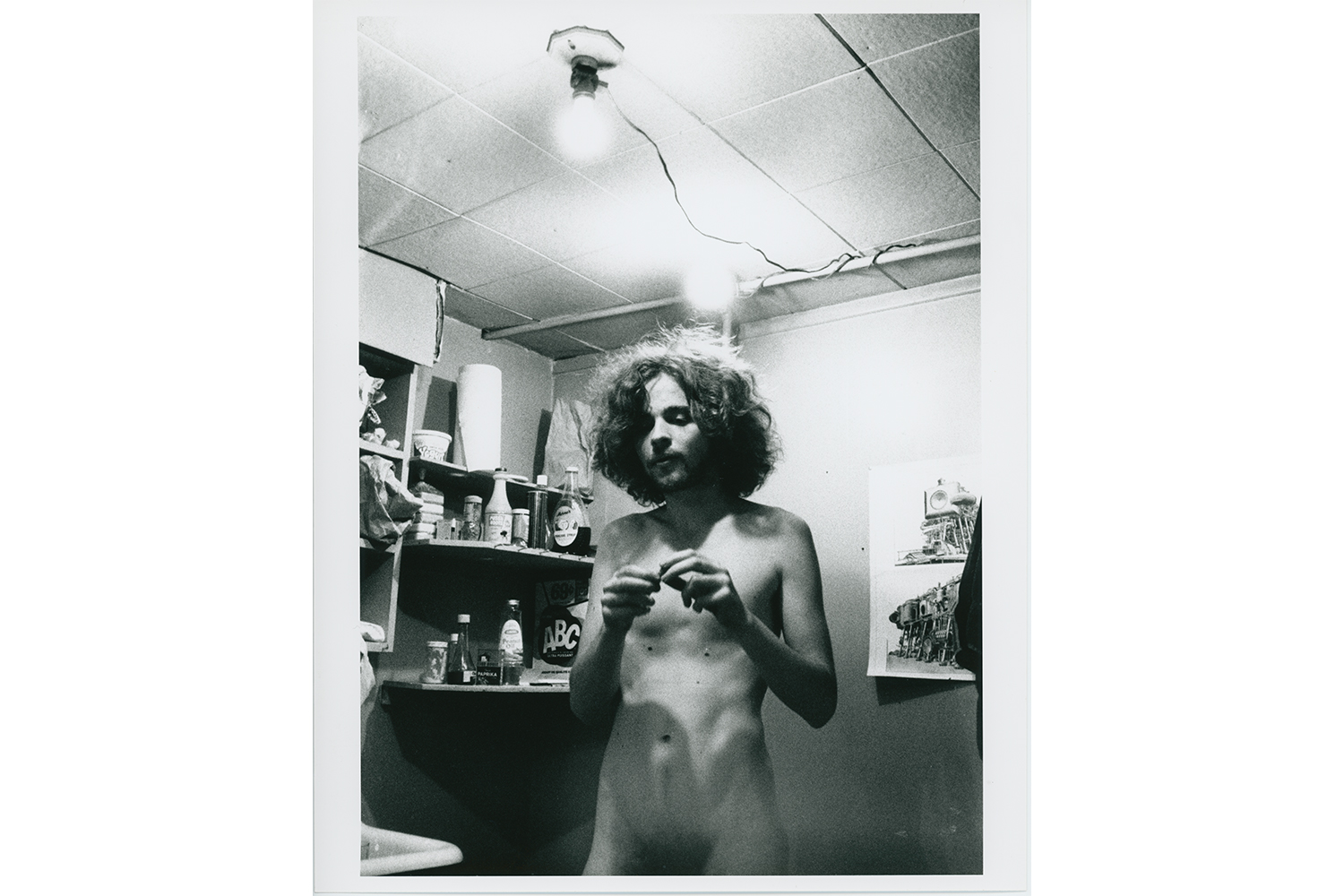

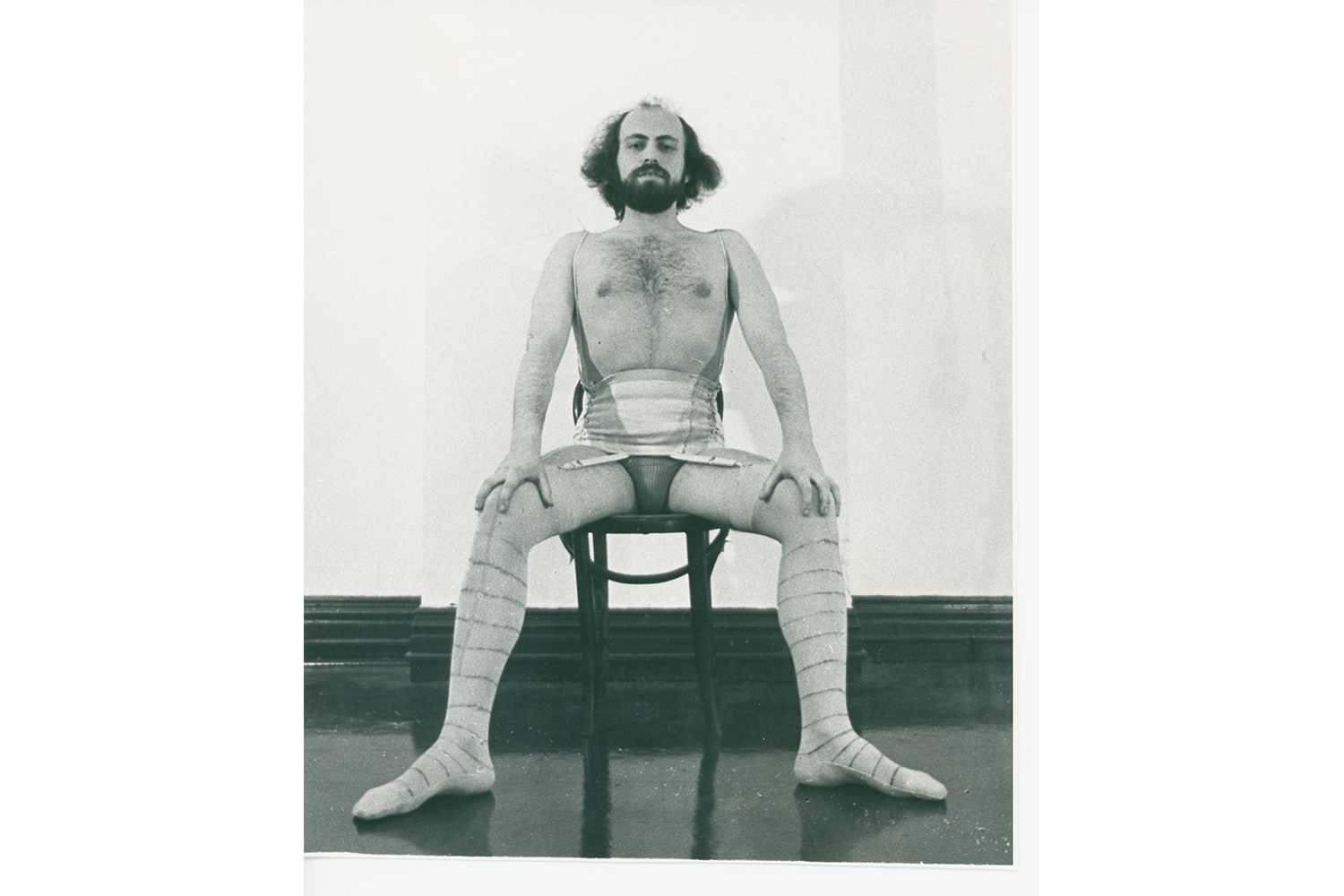

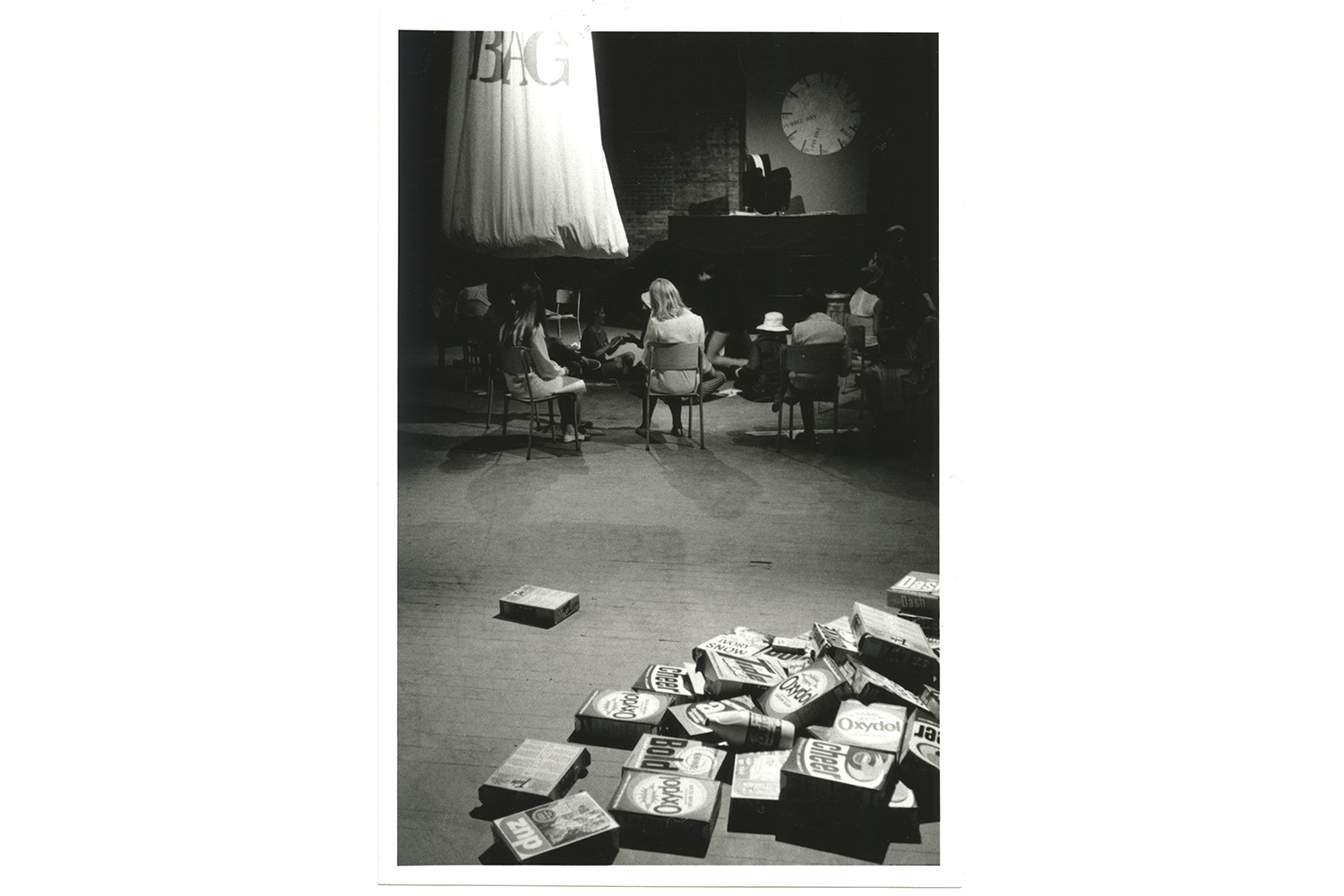

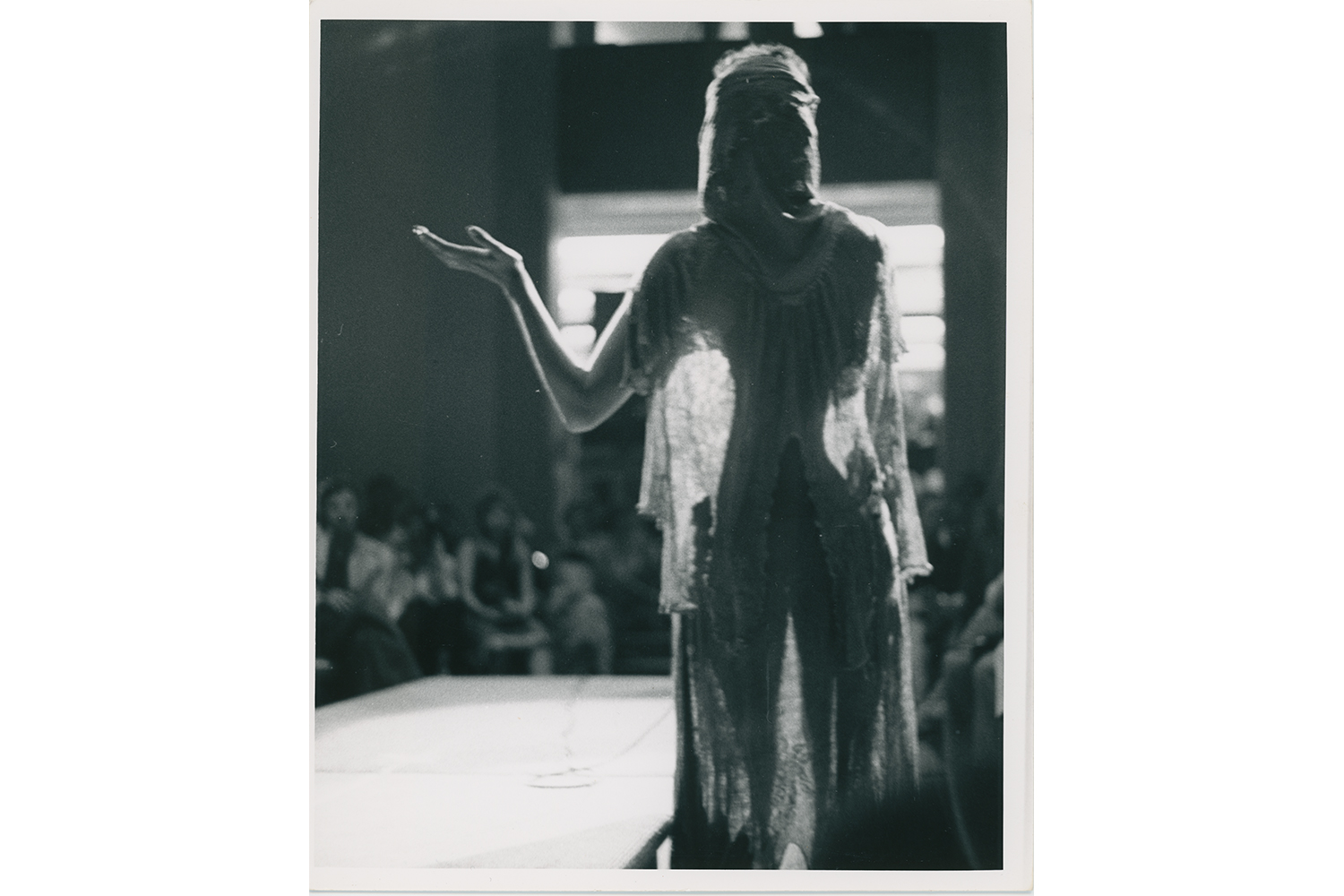

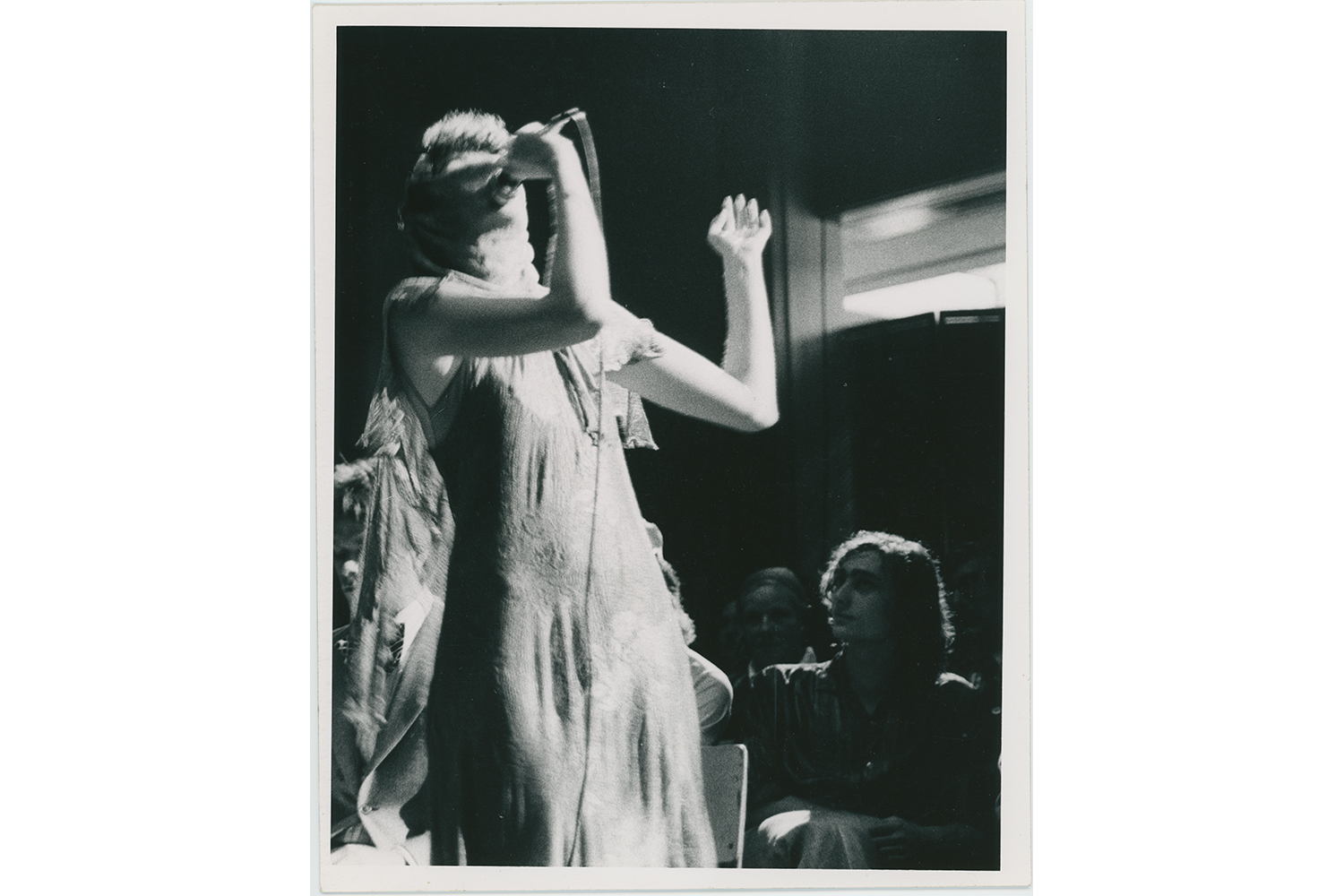

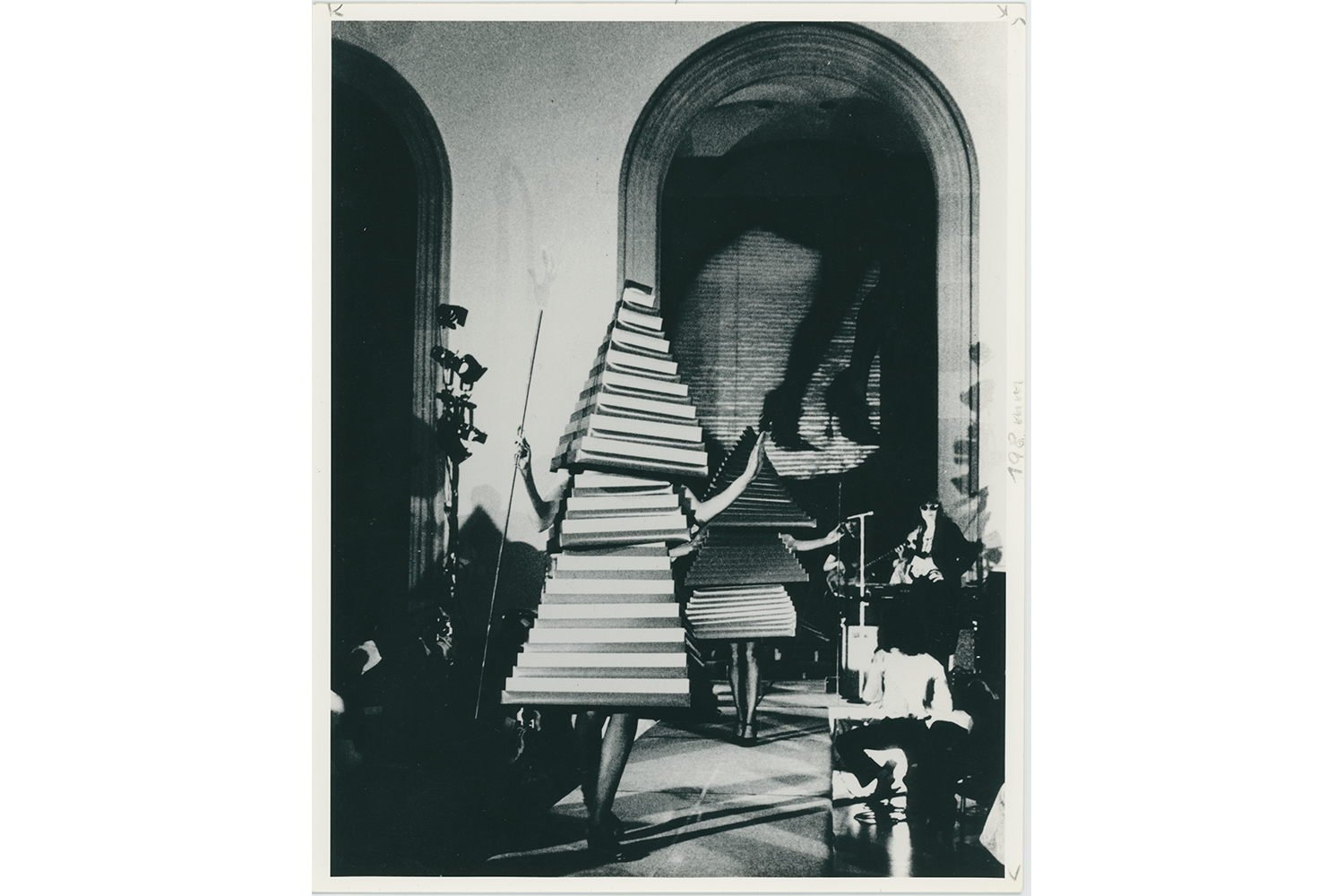

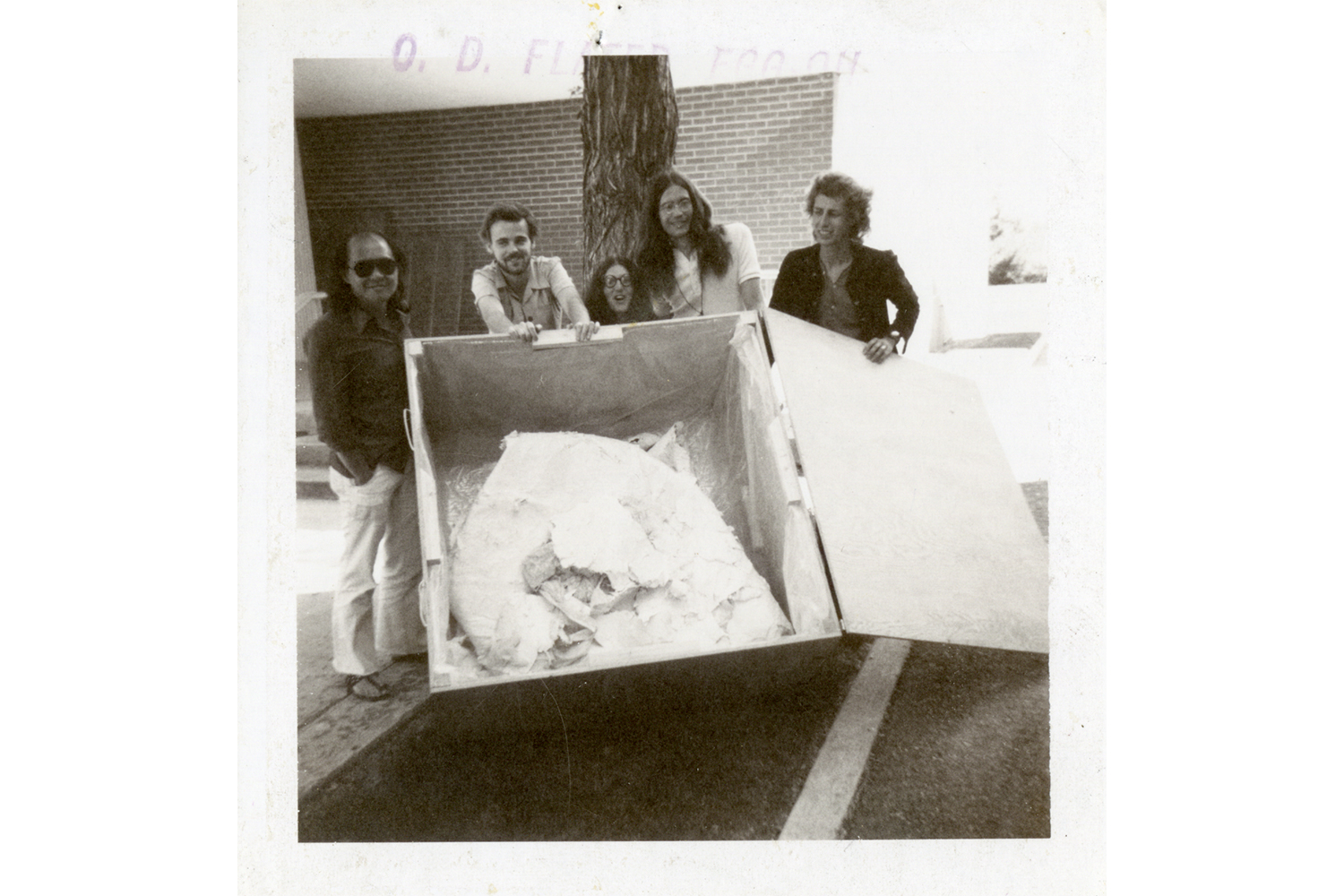

Bronson, Jorge Zontal, and Felix Partz were active as General Idea from 1969 until 1994, and their collaborative project has been discussed as a kind of proto-internet that engaged with the dissemination of information through media-based networks. They identified with parasitic or “viral” activity — infiltrating and feeding off of preexisting forms of distribution, communication, and entertainment. From mail (Opened Letters, 1972) to trash collection (The Garb Age Collection, 1969; Junkigram!, 1967) to radio to television (What Happened, 1970; Going Thru the Motions, 1975; Test Tube, 1979) to tabloids (FILE Megazine, 1972–89) and other forms of advertising (AIDS Poster Project, 1987–94; Nazi Milk, 1979–90), they pushed beyond the limited scope of the art world.

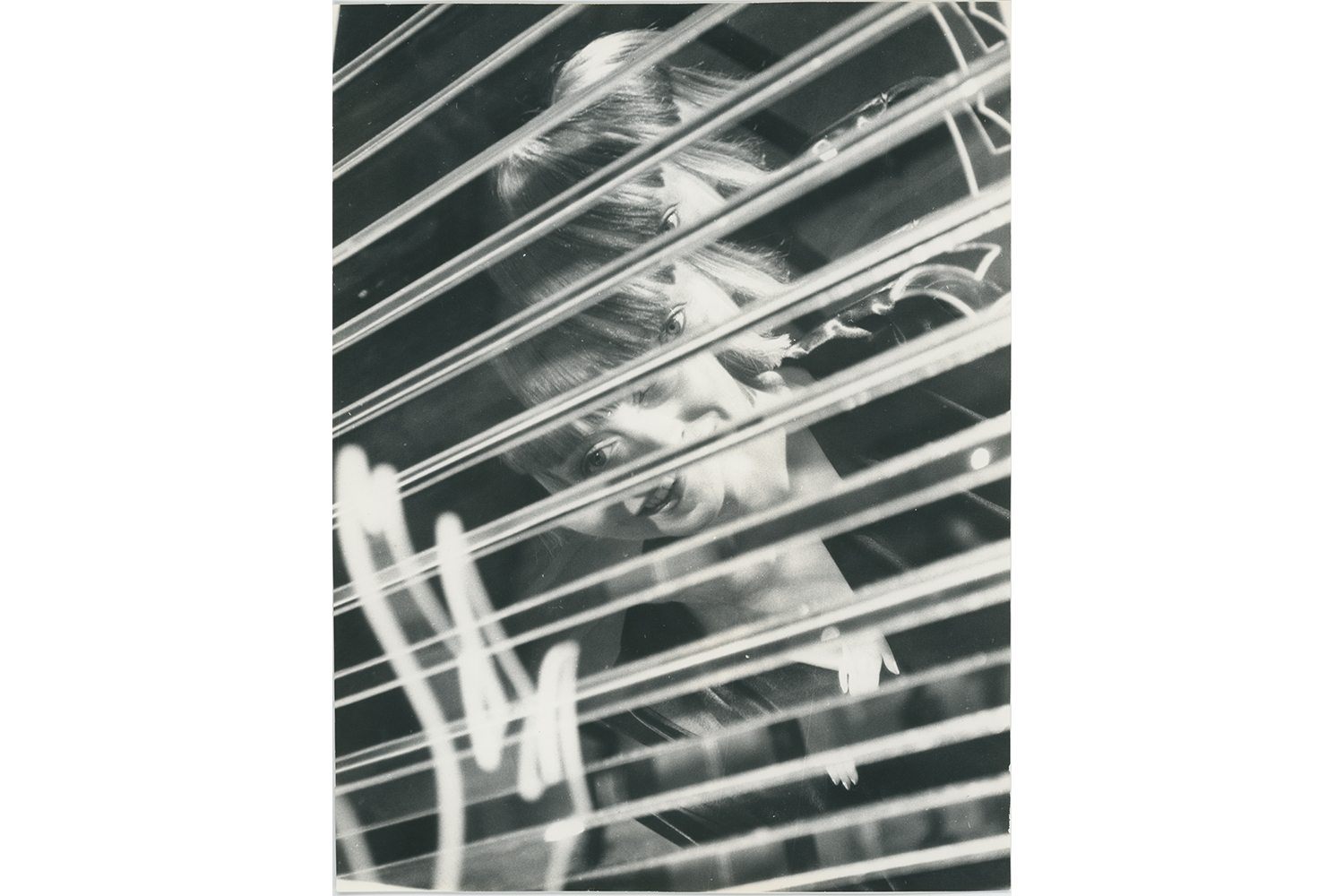

Though it may be obvious, it’s hard not to think about the relationship between the work of General Idea and social media today. When the group was founded, there was an optimism around artists’ use of new media. It was an approach that necessitated collaboration. Though there have been a number of contemporary artists using social media as their material and platform (Amalia Ulman on Instagram or Whistlegraph on TikTok), the privately owned companies involved limit usership, and thus the possibilities for true experimentation are squashed. You can’t take Instagram apart the way you can a video camera, or infiltrate it in the way that it was once possible to infiltrate public platforms like radio or cable-access television. General Idea’s total embrace of such platforms, their malleability and potential for subversion, is what makes the work so thrilling to view today.

Gracie Hadland: Congratulations on the exhibition. How are you feeling about the show? I realize it opened in Canada last year but you have a special relationship to the Stedelijk — it was where General Idea had their first institutional show, at least in Europe, right?

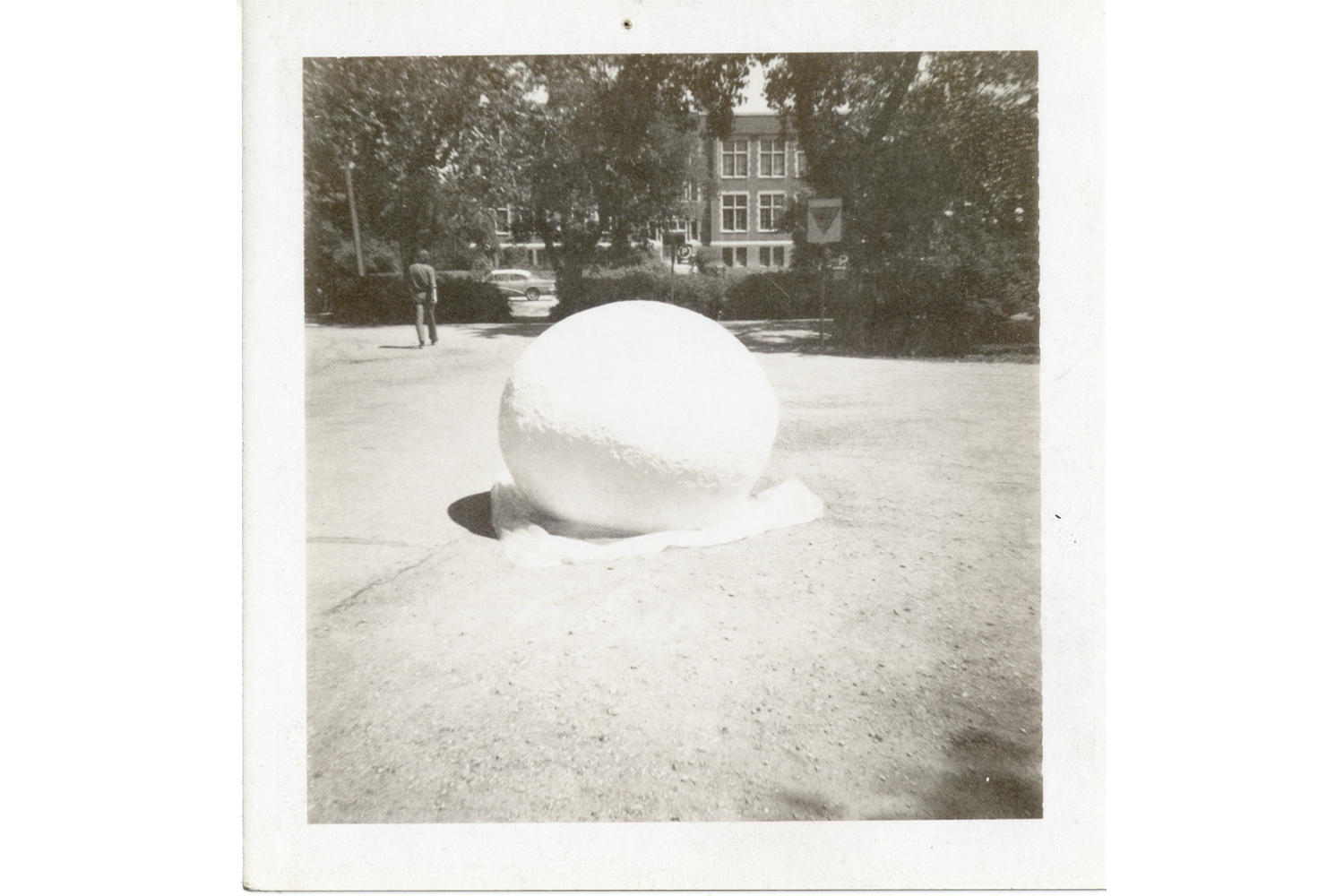

AA Bronson: In 1979 at the Stedelijk. It was our first institutional show anywhere. They had brought us to Amsterdam with De Appel for a three-month residency, and the exhibition was a culmination of that residency. Amsterdam had become our second home at that time. It was really my first extended stay outside of Canada, so that three- month period in my memory, it occupies such a huge chunk of space. I turn seventy-seven in a few weeks, and that three months in Amsterdam feels like it was eight or nine years.

It was an amazing opening. They expected six to seven hundred people at the opening, and I think it was twelve hundred. They had to give out numbers for people to get into the exhibition. A lot of young people were there, a lot of art students. I haven’t really been there for a long time, so it was nice to revisit it in that way.

GH: It’s interesting that a lot of young people were there. I think there’s something about General Idea and your relationship to media that speaks to a younger generation, perhaps because it’s much different now. Your approach to new media in the 1970s and ’80s seemed to be one of curiosity, optimism about what artists could do with these new forms, how they could experiment. I think today it’s often more the case that we’re fatigued by new platforms or technology; they provoke a kind of exhaustion rather than an excitement. Perhaps it’s the oversaturation, the gratuitousness and ubiquity that engenders a kind of cynicism. It’s hard for me to, say, imagine the novelty of video, and there’s something kind of exciting about that.

AAB: We were using television, not even video, but television in the ’70s. And video art was extremely well established by the end of the ’70s, much more than it is now in a way. When you went to art fairs, you saw plenty of booths showing video art. You don’t see any of that now. I mean, zero. The dealers in the ’70s were much more experimental too, probably partially because there wasn’t much money involved. There weren’t really collectors; nobody was buying art anyway, so might as well show whatever you really were involved with or felt was interesting. All that shifted, actually, in 1979, because suddenly painting reared its head. I mean, in ’79 there were very few art fairs, but Art Basel started in 1970, and it was the king of the art fairs, and it still is in a way. And all the dealers, around ’79 to ’80, all the dealers dropped all the alternative media, and painting suddenly took over. It’s an interesting moment.

And you have to remember that the scale is different. The number of galleries, the number of artists, the number of museums, the number of art fairs, the amount of money that’s in the art world — it’s all happening on such a completely different scale. And the amount of money means the number of people who desperately want to get something out of the art world is much greater. In ’85, I think it was Robert Longo who appeared on the cover of New York Magazine, and it was the first time an artist had ever been on a cover of a magazine. We all agreed that we had entered a new era. It’s like the world of money discovered the world of art.

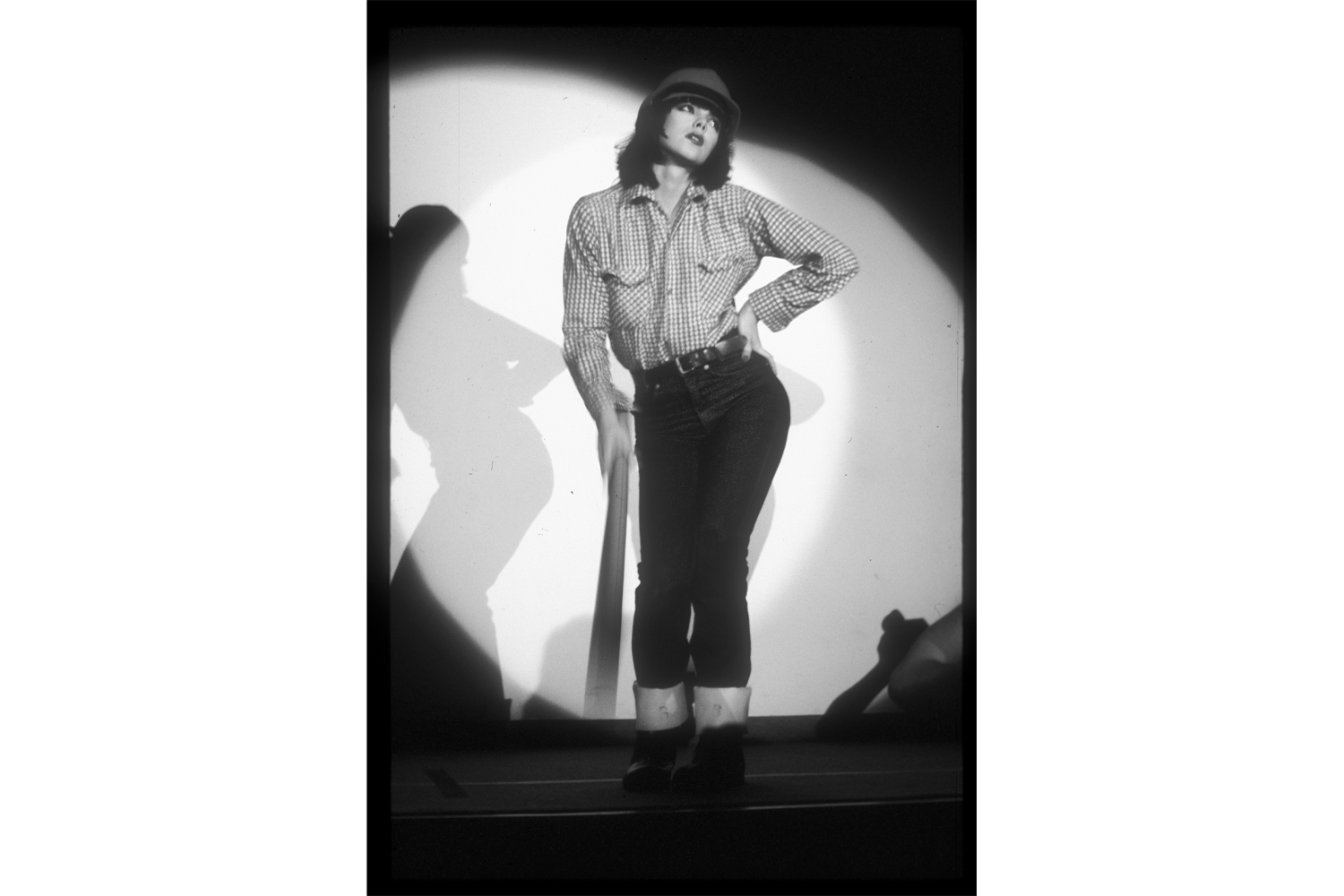

GH: Right. It was this moment of these art stars, too. The cult of celebrity infiltrated the art world. But you were kind of mocking this in FILE Megazine, using it but also obscuring the individuality of the artist within the collective. Those scenes were so small — the idea of creating these quasi celebrities among your peers was kind of a radical idea because it questioned what made fame and what its function was.

AAB: General Idea always said, you know, if we all act as if we’re famous and glamorous, then we will be. And that was really how the whole New York art world existed, in that way. I remember the first time I visited Andy Warhol was in 1973. I just went and knocked on the door and the door opened and there was Andy Warhol and Glenn O’Brien. Nobody else was there. Just the two of them. We sat and I gave them the second issue of FILE Megazine and they gave me a tour through the factory.

GH: Amazing. It’s wild how much the art world has dispersed and changed. It’s hard not to slip into nostalgia for moments like that. I was kind of wondering what you thought of the Andy Warhol series, the docuseries? Did you watch that?

AAB: I didn’t watch the whole thing. It felt so artificial to me, and I preferred to kind of leave my memories alone.

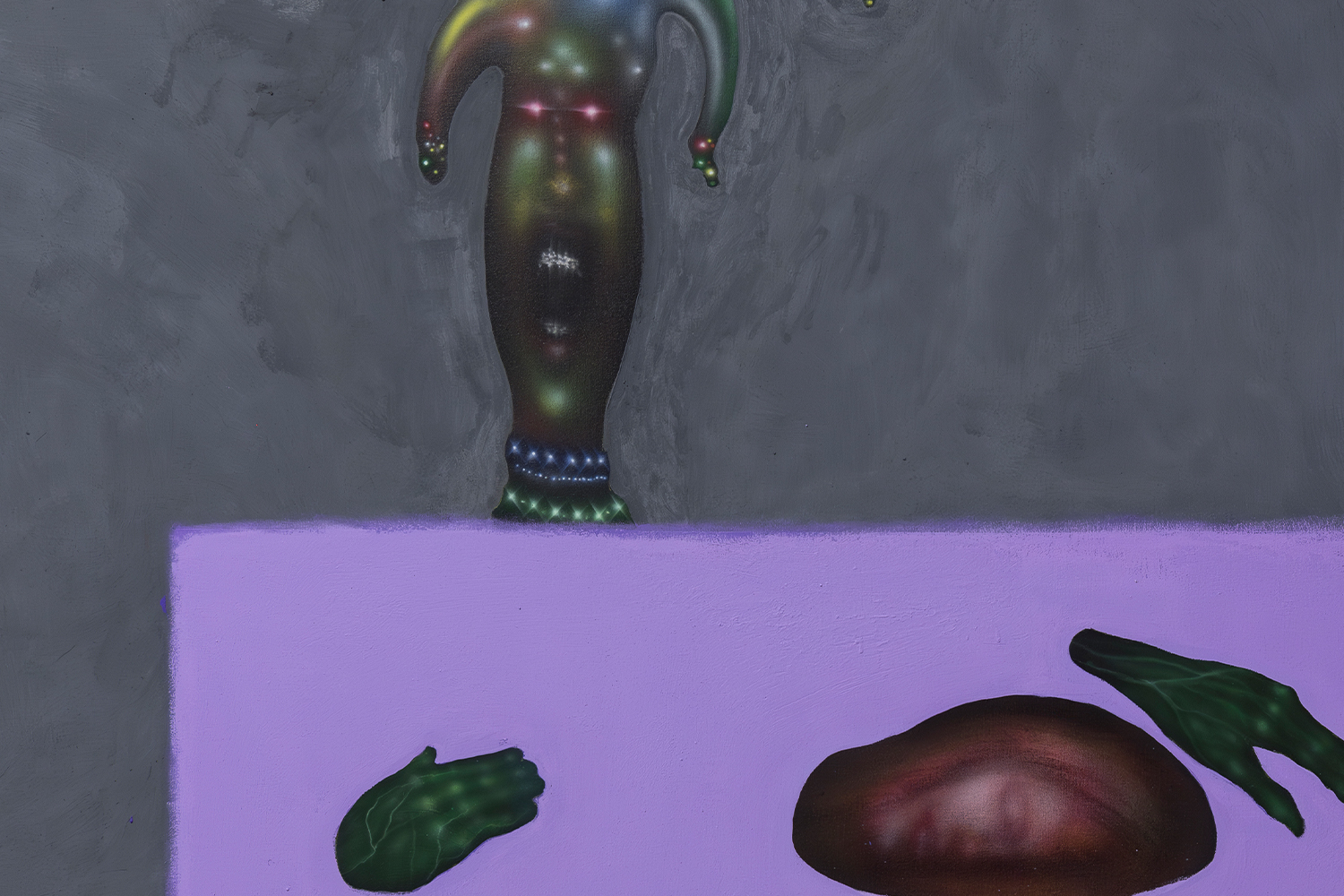

GH: I was just thinking about the way that a lot of it was about his being gay, and was this rereading of his life through the context of his sexuality. It of course can be interesting to think about his work from that perspective, but also it just kind of ends up being this clumsy recontextualization, leaning into these clichés where he’s positioned as a victim. As General Idea’s work is reconsidered in these retrospective contexts, how do you feel about that kind of rereading of the work or a kind of queer theory being applied to it?

AAB: I find it annoying at times, I have to admit. Well, it depends — the show first opened at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. They pushed the queer context, they promoted it really as a queer show. You know, sexuality just wasn’t something that you built an exhibition around in the ’70s. It just sort of floated around outside of the art world. It really shifts how you see everything once you start applying that culture of queerness to everything.

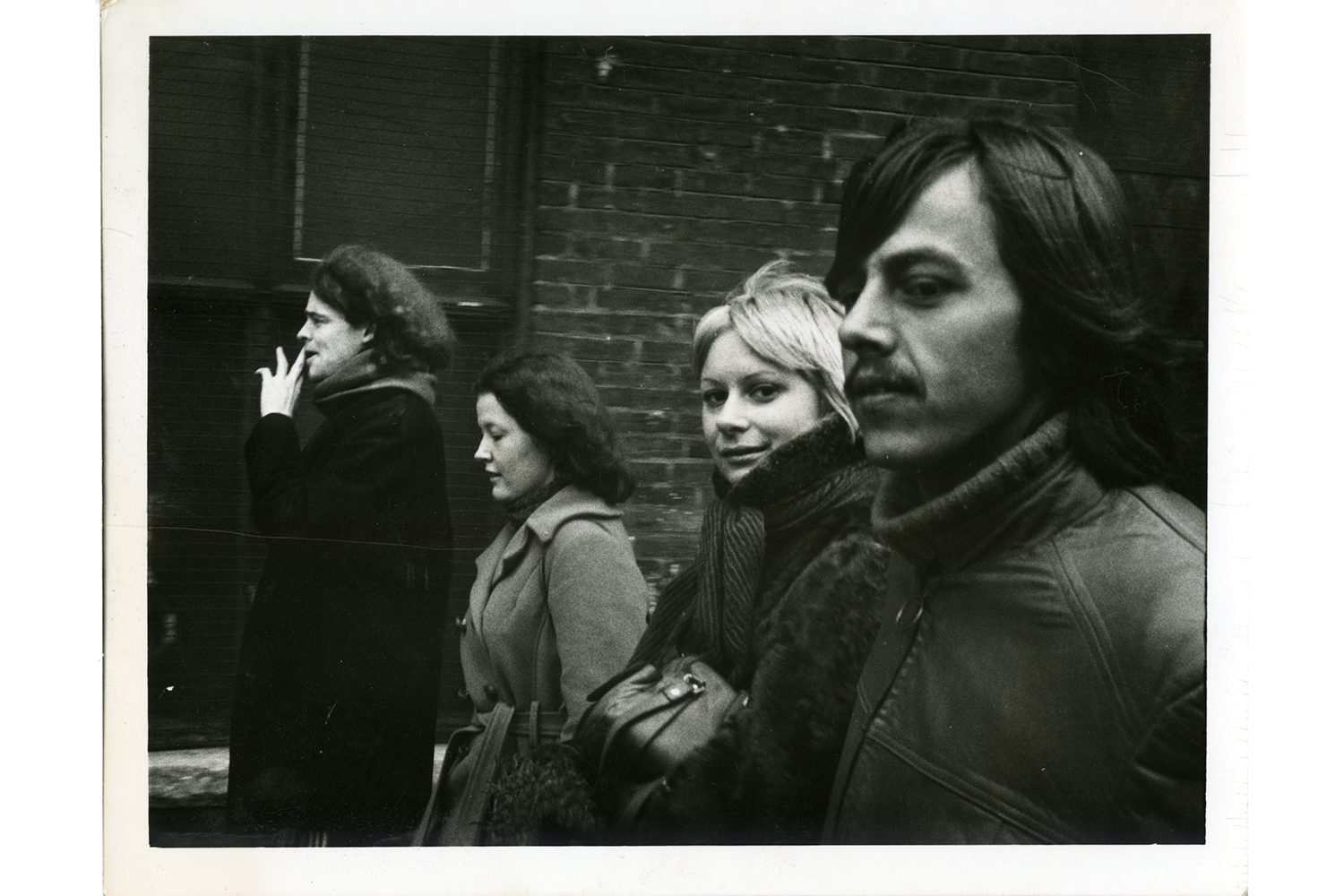

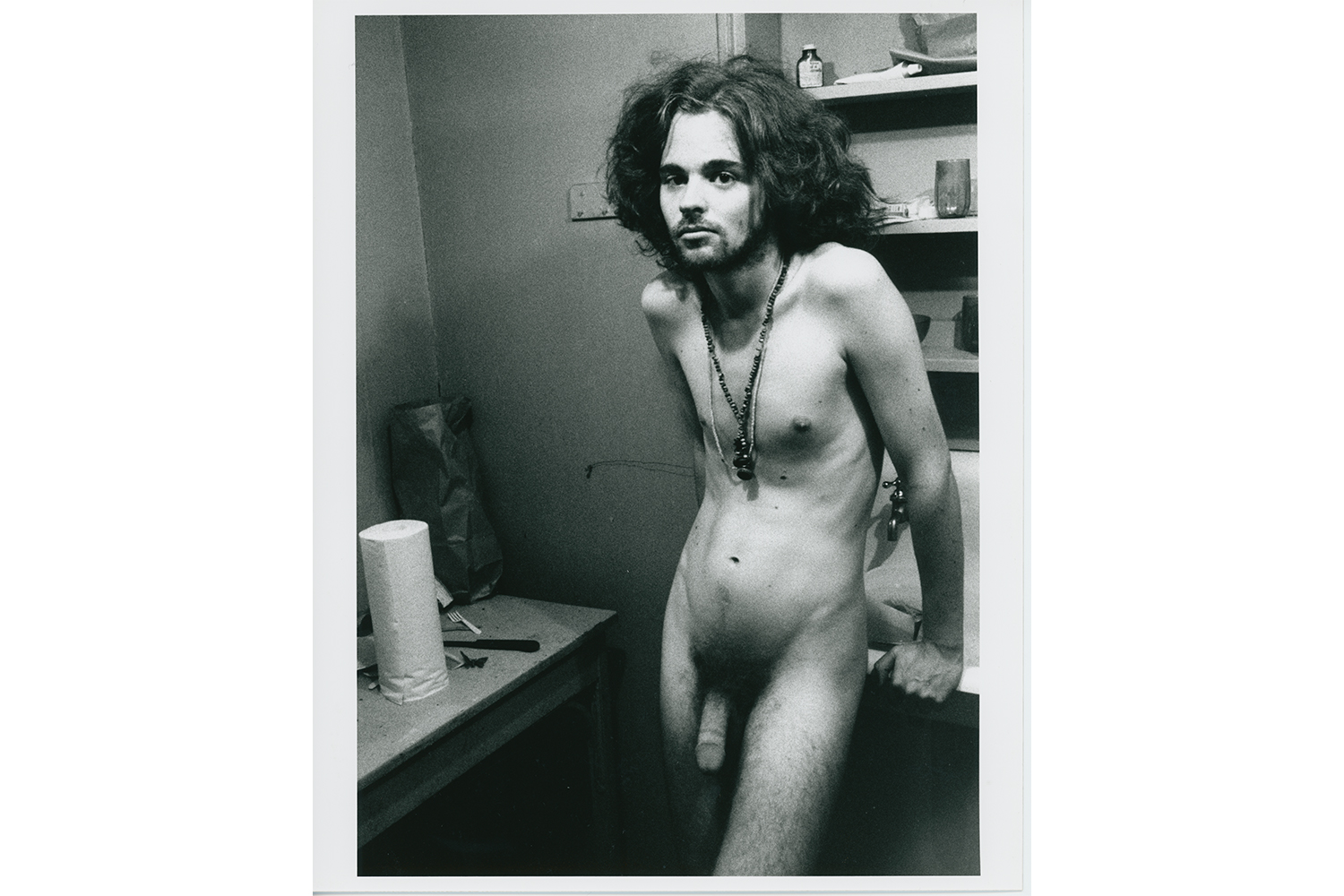

And I’m not totally comfortable with it. I’m not sure what to think, actually. The other thing is, a lot of people don’t realize that General Idea in the very early days was a group of seven or eight people. I say seven or eight because it was a kind of a loose, shifting group for the first few years.

General Idea was never written about as queer until we moved to New York, really around 1985 to ’86. Which seems astonishing to me when I look at the work from the early ’70s. Then the poodles appear. We were trying to push the audience. The critics at the time were discussing General Idea in very dry terms. There was no mention of sexuality. So we introduced the project of the very fey poodles, which were a sort of provocation to the art world. They were written about as a metaphor for collaboration, working together, but the idea of sexuality was completely sidestepped. It seems weird though.

GH: You’ve talked about how identifying oneself as a queer artist in the ’70s was detrimental to one’s career. But now, for artists or maybe curators to promote sexuality as part of the work or exhibition is a selling point.

AAB: We would’ve had no career. It’s so drastic in that way.

GH: I was also thinking about the way General Idea is framed as an activist group now. In some of the press material for this exhibition the work is promoted as “laying the groundwork for conceptually driven activist engagement for a new generation of artists.” I thought it was interesting because a lot of the work was, you know, not activist work, or it did not exist in the realm of activism necessarily. It was using the tools of advertising or dissemination, but not with a direct message or goal in the way that activism has an agenda.

AAB: We were always involved in provocation. Not activism in the sense that we were providing the answers. It was more like we were trying to get conversational. And so, I mean, the usual thing that was quoted was the AIDS Poster Project, which, I think we did the first one in ’86 or ’87. The idea of using a poster, first of all, for an artist to use a poster — posters were being used for activism at the time and even being used by artists, but for activist purposes. So in a way it was more like a publicity campaign for a disease, and in a sense that’s what it was, because the media were not using the word “AIDS”; the word did not appear in the New York Times until long after it should have.

GH: Right. You used the method of a publicity campaign.

AAB: Maybe the difference is subtle — I’m not sure — because we certainly had activist intentions, but we weren’t out on the streets demonstrating. One of the reasons we weren’t is because we were illegal immigrants in the US and we were afraid that if we got arrested we would be deported.

GH: Do you find it challenging to be in this position of representing the legacy of General Idea? What’s your relationship to that?

ABB: It’s problematic, I guess. I’ve had to kind of give up my life to General Idea in a way. When Felix died in ’94, it took me about five years just to feel conscious again; it was such a difficult period. And then I decided that, in terms of art making, that I should try to develop a body of work of my own that was definitely not General Idea. In retrospect, it was maybe a bad idea, because I was a third of General Idea; we worked together so closely for so long. As General Idea has become better known, I’ve just kind of let it take over my life, because it is my life after all. But it has been emotionally difficult at various times, trying to cope with the fact that most of my life has been represented in the past rather than the present or future. It’s kind of bizarre.