Amy Yao’s little beauties, shiny, glassy, delicate life-size fetishes, seem to play on our lost innocence. They are remnants of a hazy American dream of immigrant success, the timeless escape of California surfing, and adolescent punk shows, those primal scenes where nascent consumerism met innocent production. Their surfaces gleam like tears on a human eyeball, watering in the harsh winds of our desert of excess. Amy Yao’s first solo show in Los Angeles opened on Sunday, November 17, at Paradise Garage. The invitation e-mail featured two pictures. On the first, a slightly imperfect ball of ice cream in a glass cup, decorated with a dainty fan-shaped cookie, took center stage. The spectacle of cold, white sweetness was held up by the beautiful slim hands of a mysterious female, her face obscured under the opaque gleam of a white haze that seemed to shine down from the top left of the image, just beneath the title words. “I Don’t Care About Anything Else” could have been the words of that same girl, perhaps depicted in the second image, in which her feet and legs, bound in torn fishnets, were photographed from a reverse perspective, soles upward (souls), suggesting the unstable, sexily disheveled legs of a glass table, its top broken and discarded into the great trash heap of culture. Such are Yao’s productions, fragmented signifiers from a sea of references: cultural identity, nationality, ancestry, gender. The girl had a lock of dark hair visible under the white haze, branding her as oriental as it resonated with the fan shape mediated through glass.

“I Don’t Care About Anything Else” signals at once the purity and productive power of desire, as well as the puerility of its exclusionary field. Now that signs have dissociated from their referents, an “I” constructs its self-styled identity on a whim, randomly borrowing its foundations. Desire is caught in the glassy, infinitely exchangeable reflection of its fetishization in capital. Yao’s work unravels there, somewhere in the difference between the fetish and the collection. If the collection, in the Western world, is a “strategy for the deployment of a possessive self, culture and authenticity” and the “marking-off of a subjective domain that is not ‘other,’” she says, quoting James Clifford’s The Predicament of Culture,it is an indicator of good taste and education. The fetish, on the other hand, is associated with the “(negative) private fixation on single objects,” the savage, the deviant, the idolatrous and the erotic. We are the play of its reflections, medleys of a beautiful thing.

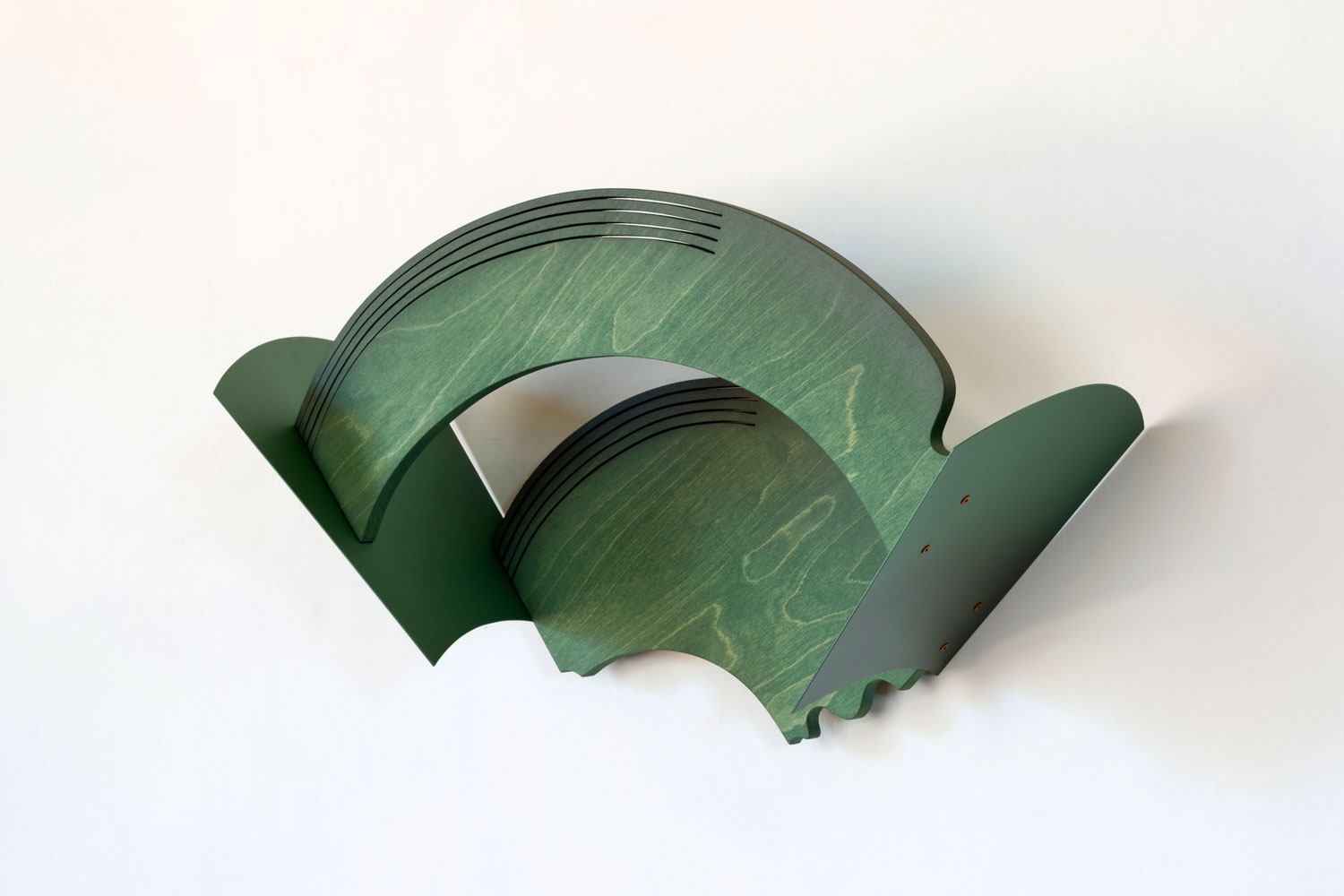

In the center of the show is a ladder. Yao uses it as a formal reference to Minimalism, but its surfboard-like resin finish likens it as well to the production of the Light and Space artists, or artists inspired by surfing such as Billy Al Bengston or John McCracken. Amy Yao has taken up the sport since she moved back to Los Angeles from New York, and loves it, she says, because she’s checked out when doing it. Surfing works as an antidote to enforced participation, a temporary hiatus to production and consumption.

The complexification of references is apparent on the ladder. It is covered in a layer of turquoise waters, where the occasional surfer blends into the stretched image of an iPhone backdrop that a friend of Yao’s sold to the tech company: transparent droplets of water on the windshield of his car. The white foam of the ocean is the thick lather of mother-of-pearl lotion, with its accompanying manicured fingernails at the tip of a pampered white hand. These are the images that saturate our world, yet they were produced by someone, maybe even a friend. Scattered over this background are inlaid small, arbitrary images collected on the internet — a Siamese rabbit, furry cats, anime-type Barbies, everything a young girl could desire —, but also specific images, such as a temporary gallery in a garbage can located around the corner from Yao’s New York studio. Texts referencing spaces and concepts, indifferently valued, are also dusted around. An apartment ad that reads “Sublet live/work” is a pithy take on the fate of precarious workers today and the merging value of art as life-work. It could be an indictment, or just what you need as you settle into a new city, a temporary place to produce your next show. Is “May” a commodified snipped of the lost spirit of 1968, or is it the name of the Parisian art journal? Most of the texts are in horror-movie font — to capture the buzz of artificially triggered affect for the media-saturated soul —, but some reprise original fonts, for recognition.

There have been several generations of these ladders. For an exhibition at Green Tea Gallery in Hawaii, Yao made a series of cheap posters of anime-type girls in red miniskirts, black flip-flops, tee-shirts and plastic sunshield visors over long hair, climbing, alone or in twos like cute twins, up the ladders to nowhere. They are reaching for a sign, it seems, in the ether. But there is nothing: only the tongue-in-cheek labels “Kauai,” “Kawaii!,” or “Maui Yowie” appear on the blank gray background of the posters, clearly in a different space. Hijacked from their work as androids in performances with the Japanese artists United Brothers, these girls emit part airbrushed perfection, part terrifying glee at their own robotic automation. Earlier versions of the ladders were less confusing in their references, because they had not yet gone through a process of integration and upward social climbing as if to mime the history of immigration to America. The first ladder was the basic aluminum store-bought prototype, decorated with stickers of pantyhose. On it, a speaker can of Boba milk tea played a sound recording Yao had made during a visit to her family in China, mixed by Eric Copeland from Black Dice. There was also an Ooga-Booga ladder — named after Yao’s sister Wendy Yao’s Los Angeles art, book, music and clothing shop — on which an image, taken from Occupy, of cats paraded lazily, sleeping through a May Day protest, signs propped up against their fur. The newer ladders, made for a show in NY, line up as in a showroom, already referencing surfing (the internet this time), but also a mix of projects by Amy’s friends.

This glassy abyss of signs provides the history of our fragility, forced as we are to navigate the contradictions of economic life. In the 1990s, both Yao sisters were members of the all-female teen punk band Emily’s Sassy Lime (ESL, a palindrome, an early indicator of Amy’s interest in the slippery nature of signs). Less important than the quality of the music, the idea was to create a world you believed in, to move in groups and have fun. Perhaps art today is sometimes the equivalent of being in an Indie band, says Amy. In the same spirit, the Yao sisters have been organizing art swap meets since 2004, first with High Desert Test Sites, then integrated into the local swap meet in Joshua Tree. Amy Yao had the initial idea with Steve Hanson, an old friend with whom she’d started China Art Objects Gallery in 1999 (The project was begun with Giovanni Intra, Mark Heffernan and Peter Kim, but Yao left after the first year). “I like this idea of small, cheap artwork, under one hundred dollars, that anybody can afford.” Over the years, the event has become an experiment, changing with every instantiation. The harsh conditions of the desert force something out: it has become a place to barter, rather than sell, to think of the situation itself and work with that. “So much art is mysterious: the way we get somewhere, how we are able to do what we do, and continue to do it. I am not interested in the mystery of that: the world doesn’t function by chance, but because someone else was very specific in their choices, by curating or creating opportunities.” Under situations of duress, the battles we wage have consequences. But these are also internal, and concern how to be critical about ourselves, about the independent projects that we are involved in, even those with close friends or relatives.

Yao’s work has long elaborated this fragility of positions. In an early work, a stack of discarded glass, jarring, cut to the wrong dimensions, nonchalantly propped up against a wall, pins the cut-up synchronicity of a fragile balance: a newspaper, folded over in what seems like a haphazard way beneath the glass, reveals the easy juxtaposition of the horrors of war with the sale of luxury items on the front page of The New York Times. The paper had been on the floor; Yao was using it as a surface to sop up the drops of plaster from something she was making. Here, the intended production is invisible; what we are given to see is the residual: found object meets scraps, what happens to our brain and our emotions in capitalism. The production of the series “Sticks” similarly blended chance and materiality. Painted dowels torn off from a layer of newspaper clippings on the floor spell titles that seem to be the stirring of some collective unconscious: Shake Up America, they say, or Don’t Bother Mommy, Panama’sAss and even Positive Highjackers.

Contiguous with the play of glass and fetishes are obscure objects of display and preservation, inscribed in histories of culture as performance. Harking back to popular festivals in Medieval Japan, parades of parasols displaying themes of aristocratic leisure and suggesting fluidity between otherwise rigidly partitioned classes, Yao has taken cheap, broken or discarded umbrellas and hung them on the wall like dead birds, sad or dismembered objects performing a debased imaginary of showbiz and empty glitter, accessorized with hair, fruit, sequins, top hats, and canes. Or she has made jars of pickled female paraphernalia: pickling spices with fingernails, hosiery, a dress, rings, eyelashes immobilized in the yellowy-green fluid of paused time. But the playfulness of these objects exudes a wise flirtation with the dreadful: inequalities of class and gender, the inevitable passage of time, and the problematic politics of object making. Her “Round Tables”perform this wise dance: dowels with fake flowers, resin thick with plastic fingernails, eyelashes, cigarette butts, and glitter are set along the gallery walls when it is empty, but when the space is needed to house new shipments, they bow and huddle in the corner in a compact bouquet.

Similar to Yao’s other objects, they mime a beautiful exchange: move aside and leave room for what is coming in. We might say the work functions by emitting a new mantra: embody, encode, show the fragility that we are. It is a gift.