I first stumbled upon Farah Al Qasimi’s work on Instagram. I’m not one to invoke my “identity” as a rationale for the copious ephemera to which I am drawn — and neither, it seems, is Al Qasimi: “I get really frustrated with American identity politics as somebody who did not grow up here. […] I’m constantly being asked to talk about identity in a way that’s not interesting to me. […] [I’m] interested in things that are informed by my identity, but not about it,” she told Document in 2019.1 I’m sure that, at least to some extent, what allured me to her photos had something to do with the fact that they elicited memories of the culture to which I feel flimsily connected as a California-born-and-raised second-generation daughter of Syrian immigrants. I speak Arabic with them but with hardly anyone else, and my time spent in the “Middle East” is limited to grade school summers in Syria, devouring cactus fruit with bare hands on my great aunt’s porch. It overlooked that same neighborhood cactus fruit stand. I’d spend hours playing on my pomegranate Nintendo perched on my own cathedral of stacked Persian rugs at antique stores. While the adults sipped complimentary black tea and perused the stock, I’d sneak into my grandmother’s special guest room — that functioned more like a storage room — to wander among the glassware, porcelain china, tables, and chairs cloaked with muslin cloths to protect from the dust that threatened to settle there.

At the time, I had no idea Al Qasimi was a photographer; I just thought she took really good pictures. Maybe I wasn’t paying attention. Or maybe it’s because, at the time, I naively subscribed to a narrow understanding of what capital-P “Photography” was/could be/should be. That (since-expired) conceptualization was trifurcated. Photography was either A) solemn portraits of serious, staring, important people à la Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936); B) behemothic landscapes — formulaically, anywhere that calls into question the intransigence of atheists around the world; or C) moments flagged as key by the fickle desire path of history, e.g. Alfred Eisenstaedt’s V-J Day in Times Square (1945), NASA’s Pale Blue Dot (1990).

* * *

Butterfly Garden (2016): ochre butterflies, membranes for wings, perched on an orange wedge, carpel beaming as twin arthropods drain it of nectar. Blue Gatorade (2021): seven titular bottles sitting on a gilded, expensive-looking, glass-topped table next to a bouquet of blue and white flowers. A phantasmagoric light — rivaling that of the mystery orb2 Donald Trump and the Saudi king together touched back in 2017 — emanates from within, as if this electrolyte-rich, PepsiCo-manufactured athletic ambrosia that I can buy at CVS for $2.49 is indicative of a greater divine. It’s Not Easy Being Seen 2 (2016): Hijabi posing as cipher against a green screen, wearing gloves and a face mask of the same fabric, every inch of her designed to permute.

* * *

Al Qasimi eschews prescriptions about what deserves to be photographed, instead training her gaze upon banalities that most would refuse to grant a second glance. Her “aesthetic tendency” is to include — her photos emanate an aura of what she describes as “so-muchness.”3 Al Qasimi frequently photographs interior spaces, both private and public: bridal flower shops, barber shops, bathrooms, and bedrooms. If, as the saying goes, a space is a reflection of a mind, the details upon which Al Qasimi fixates are not unlike the elements of the subconscious that we repress. In her performance as an artist-psychotherapist, she illuminates what we’ve neglected, coaxing uncertainties and possibilities out of the shadows and into the limelight to confront, appreciate, learn from, and fantasize about.

“My work tries to see the idealized version of everything, of recognizing the human impulse to edit, to sentimentalize. It’s a coping mechanism,” she explained to Mousse.4 What is fantasy, if not simultaneous idealization, coping mechanism, and childlike shirk of the pedestrianism of reality? Memory is, at best, only a personal chronicle of an individual’s experience of their reality, rather than an unadulterated record of Reality itself. Shards of this lovechild of the vague, noncommittal fling our minds have with the vacillating external world can catalyze the images in our dreams, which themselves are up for interpretation, for, according to Carl Jung, they contain “messages sent up from the unconscious.”

While Susan Sontag lamented photography’s inability to reflect reality, Al Qasimi questions3 the very premise of why photography is envisaged to act as its mirror. “Photography is a medium that’s constantly […] mired with these expectations about truth-telling. […] I think that’s […] an unfair expectation to place on the medium because we don’t necessarily ask the same thing of a painting or a sculpture.” Taking the world, in her words, as “raw material rather than immediate subject,”3 her work features both organic and staged moments, often recreating moments observed in her studio. Al Qasimi’s photographs are hieroglyphs of the parareal, archetypes of memory and the dreams it injects. They present insignia of another world, posturing as an exercise in dialectical behavior therapy, a sustained method of inquiry into every single truth, even when those truths are contradictory.

* * *

Piper at Barbeque in Houston (2016) is a photo of a dog cowering beneath an antique table whose surface is embellished with an ornate metallic design — perhaps in an earlier life it saw unopened coffee-table books and teacups overflowing with chai. There’s an oblong glass dish in which T-bone steaks marinate, along with three pistols, a rifle, and shotgun shells. The low light and flash setting in which the image was taken lend the dog’s eyes the hue of a fluorescent Maraschino cherry that matches the bloody meat mere feet away. It’s unclear whether the dog is sulking for a bovine treat or afraid that one of the weapons will be used against him. A laptop is strewn on the floor in the corner, but that will be useless: not even the most perfectly worded internet query will grant answers to questions that the cursed image asks.

* * *

When Al Qasimi’s subjects are people, they’re often obscured, identifying details neatly yet pointedly concealed: faces masked, figures turned away, eyes downcast. “I don’t think that anybody owes all of themselves to the world,” she told i-D in 2017.5 In an age when social media companies ruthlessly mine the personal data of their users — when every earthly denizen is encouraged to perform and proliferate a persona online that is subsequently regarded as a potential constituent of a new e-commerce startup’s target market — when your face both unlocks your phone and makes you 38% more likely6 to receive likes on Instagram — to decenter identity is tantamount to identity theft. To go incognito is to redact, to withhold, to punish. Anonymity is the new censorship. Giving too much away feels like a fair trade-off to knowing too much. Al Qasimi’s photographs slant the scales out of balance.

* * *

“Because a lot of my work doesn’t include very visible figures, I think of […] objects as […] stand-ins for figures. […] We have objects around us all the time. […] They have to be absorbing our psychic energy in some way, at the very least… we’re imbuing them with all of these hopes for what we want to be or want to represent. […] If you look enough at what someone has in their room that’s like a portrait of themselves.” — Farah Al Qasimi

When I run Google Lens on Fish Sandals (2022) — a photo of a woman wearing sandals designed in the eponymous animal’s image, leaning precariously over a balcony overlooking the sea — Google hyper-fixates on the tropical dress she wears, directing me to websites where I can purchase similar dresses: Depop, Etsy, Poshmark, eBay, Vestiaire Collective. The talismanic fish sandals are too muted for the algorithm to pick up on. But it’s not her dress that I want, nor her sandals. I want what she wants.

I’m reminded of the Little Mermaid, the half-woman, half-fish that yearned to be a complete woman. Here is her antithesis, aching for the sea, so desperate to escape that one of her slippers has fallen off. Is it an auspicious sign? — she’s so close to what she considers home that she can relinquish the aspirational couture she dons on land. Or is it an omen? — the universe’s way of reminding her that she will never be complete, that as she risks her life to become what she is not, her costume will slip away. The columns and rows adorning the bottom half of the photograph allude to a prison. “It’s tough to be a woman anywhere,” Al Qasimi retorted when The New York Times asked her7 if it was tough to be one in the Arab world. Is it surprising that the woman in her photo longs to return to the sea? In an interview with BOMB, Al Qasimi muses8 on Hans Christian Andersen’s original vision of the Little Mermaid. “The consequence of the mermaid’s longing is death […] She turns into these beautiful multicolored bubbles and just floats into the air.”

* * *

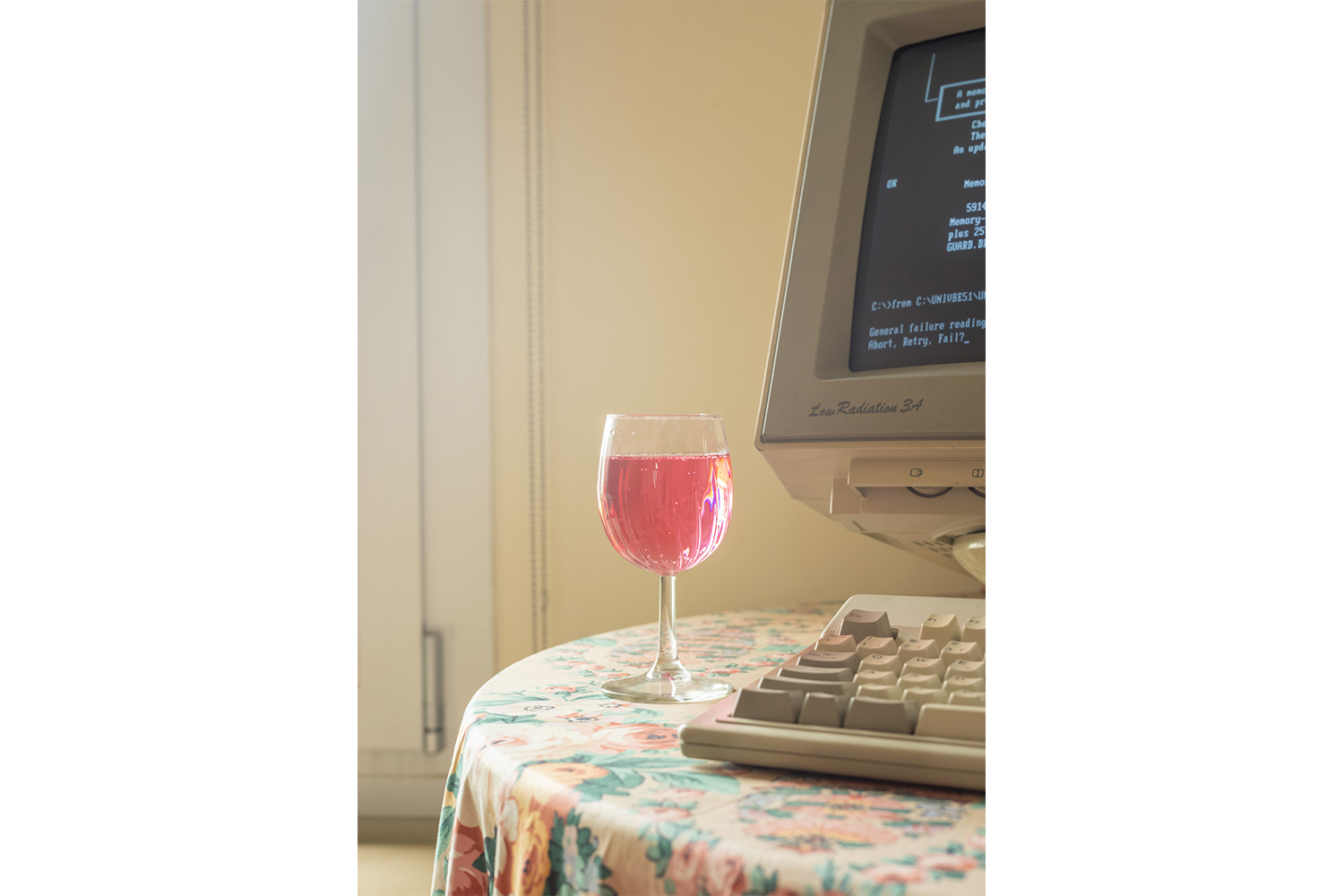

Al Qasimi’s most recent exhibition, “Abort, Retry, Fail” (2023) at Delfina Foundation, was named after the error message that once flashed across the screen of her now-obsolete family computer. It encompasses new photographs, vinyl wallpaper works, and a video, which together speak of a desire to eclipse our current reality and reach far beyond. Many of the photos feature gamers, enthralled in a third place that is excluded from the camera’s intervention. Perhaps that’s why, in Gia Wearing Contact Lenses (2023), Gia’s face is permitted to be in front of the lens unobscured as she indulges in this game-qua-psychic retreat: she is at her truest in the lives she leads online, her avatar more real than her face could ever hope to be. In Medeyyah Through The Gate (2023), a woman appears as a mirage as she stands behind a massive gate — it’s unclear whether she’s on the outside trying to get in or inside attempting to escape. A mist of red light — a color thought to stimulate serotonin — emanates an ominous energy reminiscent of an error or warning and threatens darkness instead.

The voiceless narrator in Al Qasimi’s video-of-a-video game, Signs of Life (2023), sends us on a quest. “Good, you’re awake. You’ve been asleep for a while. Was it restful? I didn’t think so. You seem tired. You have to find the river,” they mysteriously instruct. Perhaps this somnolence is an allusion to the overwhelming sense of detachment from the real world afflicting those trapped within a third place that simulates the experience of being outside of it. Perhaps this is a plea that they must reestablish connection to the natural world for which the river stands as symbol in order to truly awaken. The last thing the narrator asks of us is not to Abort, Retry, or Fail, but to “Begin.”