I did my first interview with Fabio Mauri in 1989, when I was working on an essay about the art scene in Rome during the ’60s. I had known Fabio for ten years, and we had many conversations from which I have selected the following two.

Laura Cherubini: I’m particularly pleased to welcome Fabio Mauri, our guest in my seminar devoted to the relationship between art and cinema which, together with theater, was his main interest. He was, together with Mimmo Rotella, one of the two Italians to be invited to the large exhibition organized by MOCA Los Angeles [“Hall of Mirrors: Art and Film Since 1945,” 1996]. More generally, he has been working on an issue that everybody’s talking about nowadays: the relationship between art and ideology.

Fabio Mauri: I will start right away by showing a series of Schermi (Screens, 1957-1994). At that time, Coca-Cola was the symbol of consumer society. I was trying to find a symbol that could be compared to this immediate American symbology. In the end, like a complex system forming, I found it: the screen and its liturgy. Even before starting a movie, this screen was for me a sort of absorbent paper. It would give us a reality that had already been judged. With these premises I made the first screen, drawing a black frame on a white sheet of paper. The result was a space losing its identity as a drawing. That was a screen on which you could project, draw… I called these artworks ‘prototypes.’

The painting is a conventional space. It’s obvious that on the walls of old churches the painter was painting a sort of big comic strip that was an interpretation of reality. Since I was a child I have been drawing, painting, writing; the screen was something to begin with — a surface ready to gather images, but it was also a closure. Reality was filtered through the ritualistic use of the screen. There was a speed relationship between time and velocity. Action painting master de Kooning was a guest in my house. I asked him “Master, what is painting?” and he said: “The authentic painting is the word.” Therefore painting is like an exchange, a provocative discourse that is charged with suggestions. Don’t think that anyone can be an artist. We are all expressive beings but the artist is blind, humpbacked — at the edge.

LC: We are looking at an important work: that drawer full of domestic objects that Michael Sonnabend was fond of. It’s interesting to mention this work also because of the relationship that was going on with the United States at that time.

FM: Although I was already exhibiting in very good galleries in Rome (La Salita and La Tartaruga), nobody was willing to take this drawer until it got exhibited in a group show. Three people were standing next to me: Michael Sonnabend, who was a great art critic without having written a single word; this young boy, who was upset with this drawer, Francesco Lo Savio; and finally, a young art critic from Germany, Udo Kultermann. In 1964 there was the arrival of American Pop art. We were totally surpassed by that world, that of consumer society. All the painters were thinking “We were right,” but not me. I thought this was like Pearl Harbor. All the American painters visited our studios but the consumer society was theirs.

For three or four years I decided not to exhibit. I was just making works using the solid light technique that was a way to reconnect to the Futurist tradition of Depero, whose work employed light as solid material. I went back to my childhood. The destiny of a human being is driven since the very beginning through physicality, behavior, personal will… but this is not enough. The fact that I was blond and curly-haired is less incidental than the fact that I’ve experienced Fascism and war. It was a constitutive part of my being. Therefore, I realized that the real topic of Europe was something quite impalpable: it was ideology. Going back to the emotions, I remembered that at some point my schoolmate sitting next to me — his name was Tedeschi — didn’t come to class anymore. “He’s Jewish” — they whispered. He was the first of a long series, like Gian Luigi Banfi, architect of the BBPR, who was deported to Germany and never came back. So, in 1971 I made the performance Ebrea (Jewish female). During Nazism, entire social groups were taken out like objects. Here a student of mine was cutting her hair and pasting the Star of David on a mirror. Some of the objects were formalizing what we saw from the Buchenwald production: soap, a dental prosthesis, a razor… the show was quite shocking and protested. What makes the Holocaust so aberrant is the extreme rationalization. At the beginning the show seemed beautiful, it seemed like a design showroom, then the silence came and, at the end, the desperation.

Adorno wrote that after the concentration camps it would be impossible to speak, to make poetry. I’ve always been opposed to this assumption. I really don’t know what art is — perhaps it is the cognitive coming together; it presents shades that you then realize to be fundamental. The same year I made Che cosa è il fascismo (What fascism is), which restages a German and Italian youth party I took part in 1938, together with Pier Paolo Pasolini and Francesco Leonetti.

LC: Francesco Leonetti has taught for many years at this Academy [Brera Academy of Fine Arts, Milan]. He was also a very good friend of Pasolini and he appears in many of his movies. Also Fabio Mauri appears in Pasolini’s movie Medea.

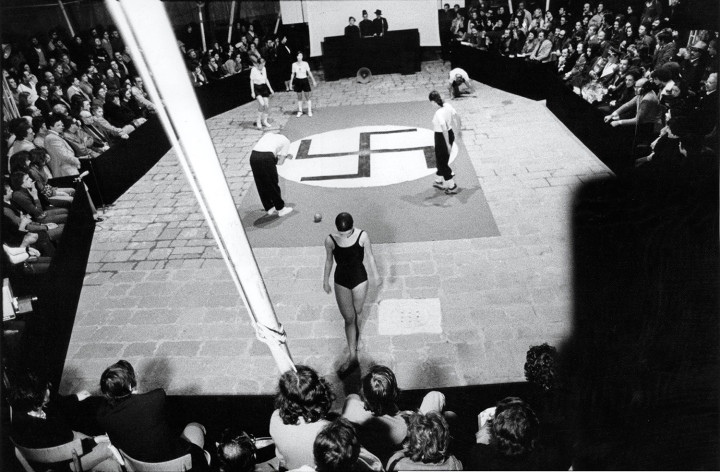

FM: From that meeting I took the gospels, the gymnastic races and the debates about the Fascist ideology. I didn’t want a stage, I wanted a stall. At that time bleachers were organized based on Fascist social distinctions created by the Fascist corporazione. When I made Che cosa è il fascismo there were more people than there were seats available. I included a bleacher for Jews where Alberto Moravia, Natalia Ginzburg and my ex-wife, Adriana Asti, were seated. Some Jews didn’t want to sit there at all. This was a way to make clear that the Fascist State made normal things that weren’t normal at all.

LC: Where was it staged for the first time?

FM: At SAFA Palatino Studio in Rome, which was a Fascist-style building. The audience was huge. The party was in honor of the wax mannequin of a Fascist general. In Italy it was performed for the first time with a 12-person company. In 1977 it was restaged in New York at Performing Garage with 44 students from NYU. There was the fencing, the dance as a celebration of the formalization of the musical symbol. In New York I added a new piece, which was a Kendo match — a reference to the three Axis powers: Italy, Germany and Japan. Fascism and Nazism were highly seductive and modern, very modern.

Then there’s the performance entitled Natura e cultura or Ideologia e natura (Nature and culture or Ideology and culture), that was staged for the first time in 1973, and then repeated many times in Graz, Vancouver and Amsterdam. A girl wearing the Fascist Youth uniform1 is taking her clothes on and off with a genuine mood and in a totally subjective way. In this way the uniform gets destroyed while the body rises up with all its authority. The clothes themselves can mutate the ideology — they can be either Pulcinella or the Ku Klux Klan depending on the context. Intellettuale (Intellectual, 1975) is the performance made with Pier Paolo Pasolini. I projected his movie Il Vangelo secondo Matteo on him. At a certain moment, I went close to him (he had a quite rigid posture) asking if he was tired of being still. He said to me he was unsettled because he couldn’t figure out which scene of the movie was being projected on his chest.

(2001. Brera Academy of Fine Arts, Milan)

_______________________

Our last meeting occurred on April 30th. The magazine assigned me to conduct a long interview with the artist and he was very happy. We had to postpone it many times because his health was getting worse but he really wanted to do it, therefore we decided to do it over several encounters. We managed to do only the first one.

LC: Shall we start with your family? I’ve always thought that the fact your father was a theater impresario constituted an interesting element. Were you fascinated by your father’s job? And what was your mother’s name and where did you live at that time? Was your mother’s family already involved with publishing?

FM: My family was all over the place. My father Umberto was originally from Puglia, I was born in Rome and baptized in Saint Peter’s Church… Our place was invaded by actors! My mother’s name was Maria Luisa Bompiani, she was a lot of fun. We lived in via Nazionale nearby Teatro Eliseo. Then we moved to Piazza Navona. My grandfather was the youngest general in WWI. He was the chief of the section in Verona. In the city there was a genius, the young Arnoldo Mondadori, who came from Versilia [Tuscany] with many adventures and he left a legacy — a kiosk of books. I studied in Bologna, which is an important chapter of my life. I studied at the so-called gymnasium or high school, studying Greek. I had many precocious encounters there.

LC: Pasolini and Leonetti were older than you. How did you meet Pasolini?

FM: My father moved to Bologna and lived with me and my sister Silvana, who was a close friend of Pasolini. They were doing a magazine called Il Setaccio. That was the smartest crew of young boys in Bologna. Leonetti was working on a book about Giovanna Bemporad: this girl who was incredibly clever. My father decided that every Sunday our house would host his childrens’ friends, and Pasolini was always at my place. We lived in via Sassi, then we moved to a huge place in front of the station. Pasolini lived with his mother, his father and his brother Guido.

LC: Who were the other poets? Leonetti was working on Roberto Longhi’s magazine Paragone. What was the aim of Il Setaccio?

FM: Leonetti was a writer but not a poet. He was more avant-guard because his culture was “post-Longhi.” Leonetti and Pasolini were cultivated, they loved Longhi also for political reasons. The aim of Il Setaccio was purely poetic. But we also played soccer. The house in front of the station was destroyed by the first bombardment. We had a place in a marvelous square up on a block called Le Sette Chiese. We have always had big houses…

LC: … and this — together with your father’s resources and the fact that you were many siblings — made your houses real gathering places.

FM: Completely! We moved to Milan in via Cappuccini and my family suddenly became Milanese. The house was comfortable. For many years I worked with my uncle Valentino [Bompiani] at the publishing house, a deeply formative job. At our place the atmosphere was warm and cultivated, a bourgeois family with a bit of Shakespeare.

A few days before, April 21st, Fabio had touched on a very important point, which is thought to be a limitation of Italian art but could also be considered a strength. He greeted me with this statement:

FM: There was and there always is Italian art. We have to think about this. Tonight I woke and thought: I’ve always been making avant-guard art but in the end Italian art is “classic.”