Originally published in Flash Art no. 324 February-March 2019.

When I was thirteen, Etel Adnan and Simone Fattal, who were friends of my mother’s, would come over for dinner. I remember Etel once talking about the time she was a secretary and General de Gaulle came to Beirut. It was at the end of the Second World War, at the moment of Lebanese independence from the colonial Mandate. I put my head in my arm on the table and daydreamed about it. I thought that when I was older I also wanted to participate in history. Now I am older and I’m rereading a book that they published at about that time called Journey to Mount Tamalpais. Though it lay around the house, I’d glanced through it then and not understood. The book is about a mountain in Marin County, California, and about painting.

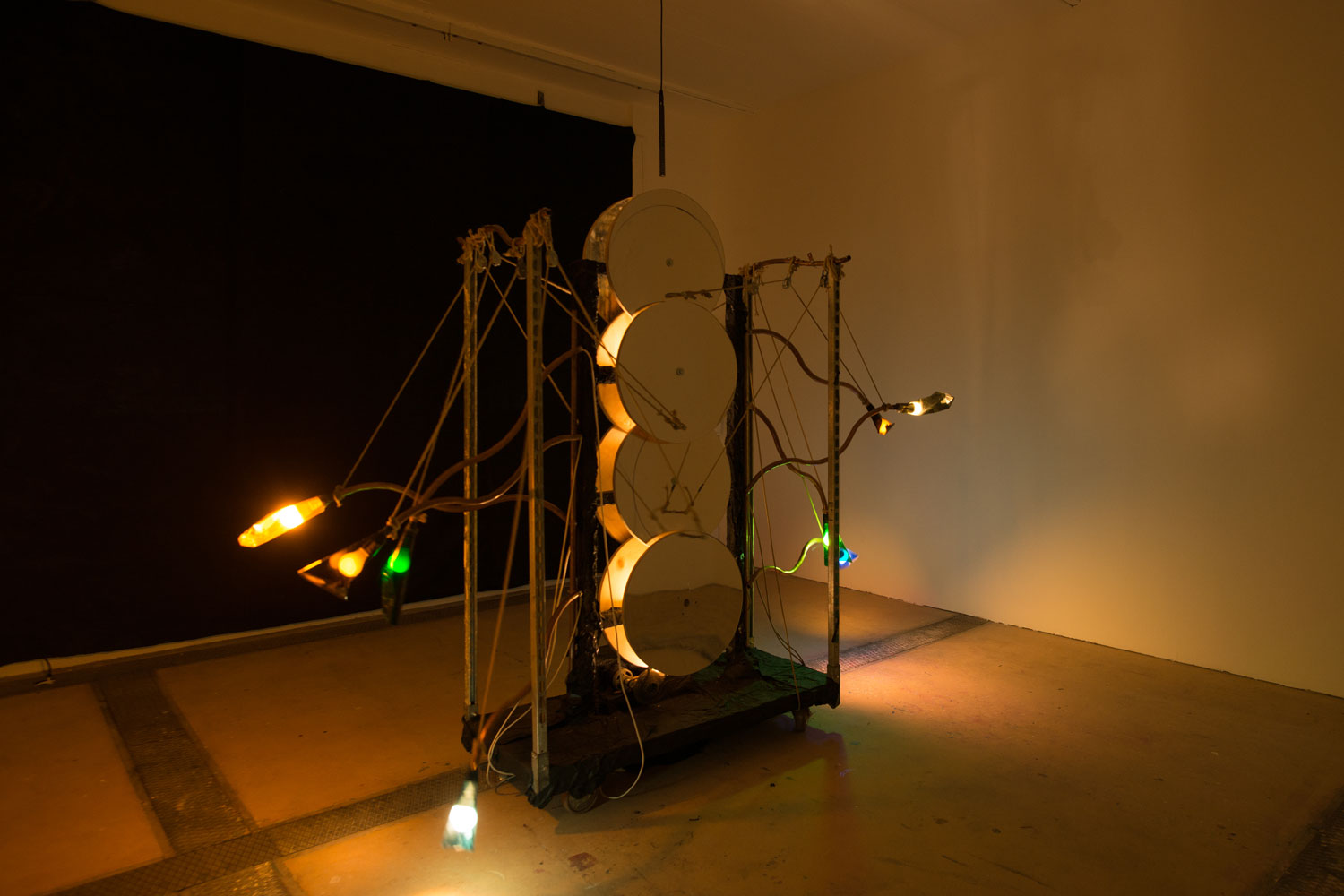

Having lived more than a half-century with Etel’s paintings, her partner Simone, a sculptor and publisher, says this: “They exude… and give energy. They shield you like talismans. They help you live your ordinary life.”1

In the West we haven’t much listened to our elders, although we need them so. Perhaps now the time has grown so dire that we can listen. But when we do listen, we often act as if we’d just discovered them, although they’ve been there all along. And worse, we act as if they could deliver talismans to us pre-prepared. They don’t. Talismans, or beliefs for that matter, don’t appear out of thin air. Talismans are made, just as belief is shored up, or as paintings are painted, and perception is trained. Etel has spent her entire life making them. She makes each painting quickly, in one sitting.

How does one make a talisman?

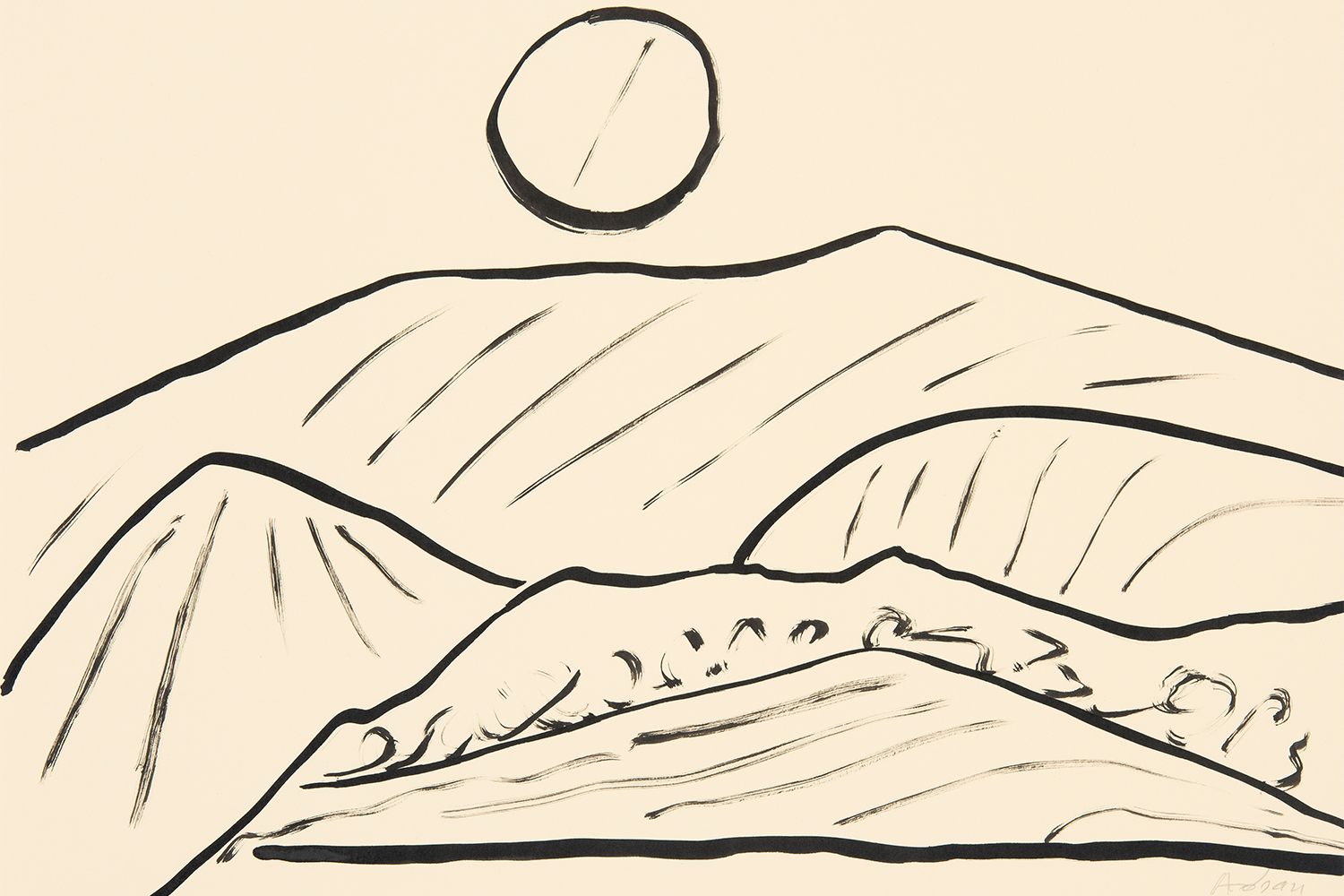

If you are lucky, you find a mountain. The mountain is the acceptance of things as they are, like the moon, the sun — cosmic events on which we have no bearing. Beholding its slopes cracks open a space of being. Here it is called Tamalpais. “In this unending universe Tamalpais is a miraculous thing, the miracle of matter itself: it is something we can single out, the pyramid of our own identity. We are, because it is stable and it is ever changing.”2 For Etel it is a “spiritual concept.”3 To paint it is to be returned to soundness: focused perception married with the adaptability and openness of not knowing what will come. Painting the mountain again and again, as Etel did, was “sanity resolved by visual means.” Her painting follows an act of will — for sanity — to step out of the death-walking or death wish of the contemporary world. “Sanity is our power of perception kept focused,” she writes, “and it is an open-ended endeavor.”4 It provides a way to look hopefully into the uncertainty of the future.

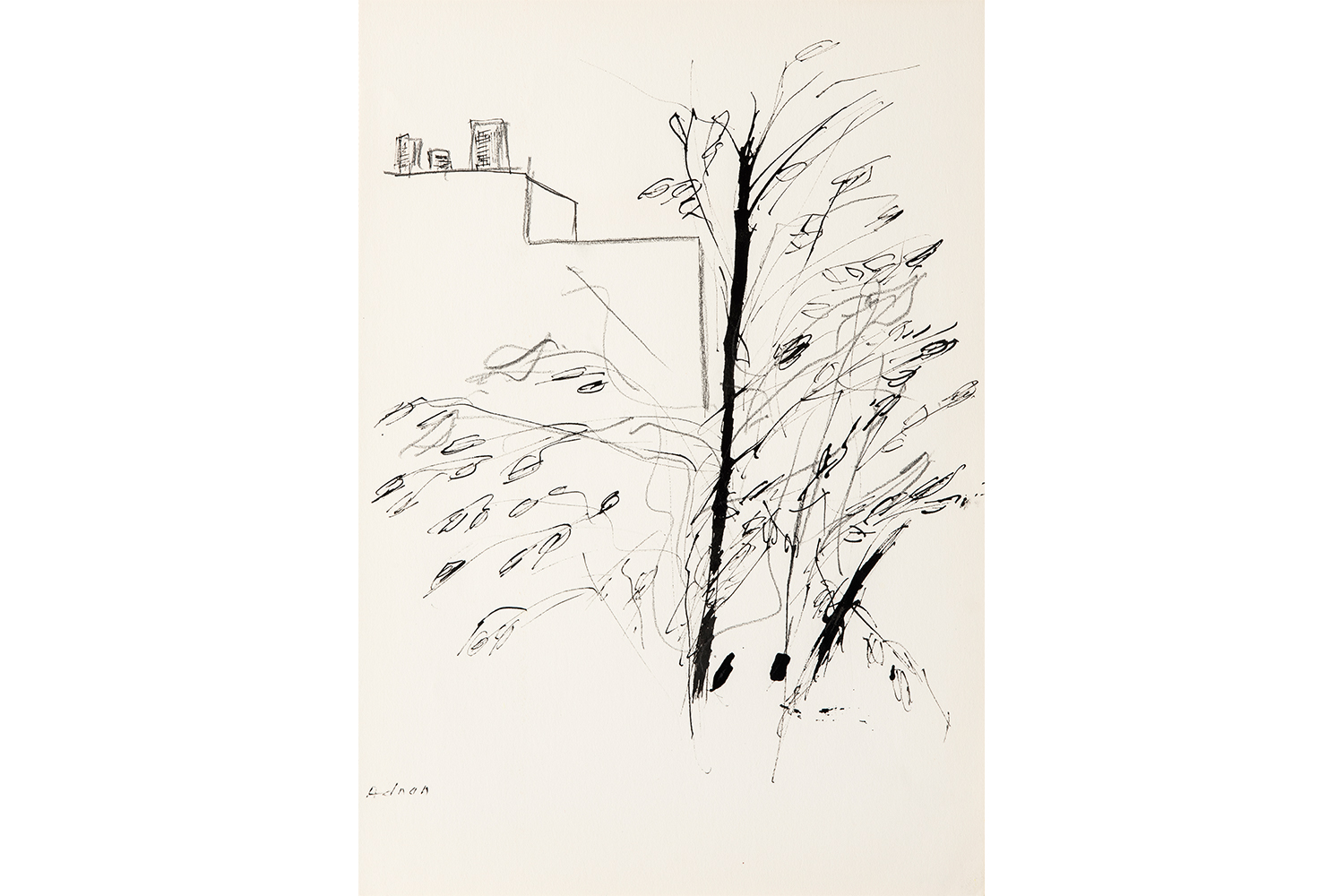

And also, luckily, it was Etel’s destiny, she writes, “to join in a great experience: to live with the mountain and with a team.”5 We paint with a team, necessarily, even if we are alone. For Etel this was the Perception Workshop, a group centered around the artists Ann and Richard O’Hanlon and involved in the exploration of perception. Their interests stretched between Carlos Castaneda’s Yaqui teachings and the ideals of the Maoist Cultural Revolution, seen from afar. They played with utmost seriousness at the foot of the mountain. But the team also included the larger sociocultural references (and events) in writing, painting, and politics within which Etel worked. And so there was the political ferment of the 1960s and the “newness of the world” that seemed possible at the time. The references for poetry ranged from Dante, Hölderlin, or Rimbaud, to the literary critic and teacher Gabriel Bounoure and the sphere of Arab poets and writers that he influenced, Edmond Jabès, Salah Stétié, Abdellatif Laâbi. For painting, there was Dürer, da Vinci, Hokusai, Turner, Klee, Cézanne, but also the painters Etel had befriended in the 1960s during her time in Lebanon, Helen Khal and Saloua Raouda Choucair.

When someone in our field of sociocultural references dies, something shifts in the pull of spacetime that organizes us. Journey to Mount Tamalpais mentions George Jackson, but does not elaborate on his death. It does, however, linger on the death of Richard O’Hanlon. He died, Etel says, but his spirit did not. In fact, death made his spirit more transparent to those who knew him. By this she means that his spirit became more present, and that what he’d done in life was clarified and revealed. The new transparency of his spirit affected a way of seeing life, and of holding it close. “Since he is no more in his usual ways among us, life became something we hold to be more fragile than we knew but also dearer to us all.”6 In his death he came closer to the mountain, to the simple materiality of what is. And his new transparency made his friends bear life more carefully, grow more attuned to how fragile and precious it is.

Tamalpais holds this transparency in its modern name, which combines words from the indigenous Coastal Miwok language and the language of the Spanish colonizer. Tamal-pa, “the one close to the sea”; mal pais, “bad country.”7

In the bad country of the colonizer the condor is dying. After having stolen native land, we sell the bones of the Indians. New highways pierce through Old Woman earth, and she is plagued by wildfires, caught in the “darkness of battle-ships.”8 In this bad country Vietnamese convicts become CIA operatives to save their skin. The earth is white, as if under frost, held down beneath the white terror of the twentieth century: “the great white mushroom, the white and radiating clouds, the White on White painting by Malevich, and that whiteness, most fearful, in the eyes of men.” And we are made to live under the white of media, television, “white, pale as God… masterminding everything and projecting the ant-like destinies of us all.”9

But the superposition of the mal pais over its ancient form has left that old form still alive, if necessarily transformed, transparent in the sense of possessing greater power to affect those who perceive it and of changing their way of bearing life. As the one close to the sea, the mountain remains as it is, even if the highway at its feet annoys it. It has the transparency of what is fragile, what is precious and must be cared for and cultivated. Of course, descendants of those who lived on it prior to the conquest are still around. But that is not what Etel is talking about. “Tamalpais is a space-launch and the Tamal Indians knew it: they are still living on it, transformed into trees. Some of them are madrones, others are oaks.”10 This facticity still inheres in the mal pais, beneath the judgment, beneath the obsession with reason, beneath the selling out of life.

This is perhaps one way that paintings can be talismans. They show us that transparency. They point us to freshness. In Etel’s paintings the mountain is green or blue; it is the color of spring and sea. Sometimes there are swashes of green inlaid within a larger green color field. Etel does not superpose colors, although at times you see a sliver of moon in the sun (Untitled, 2018).11 Her paintings are continuous ruminations on that green, that spring, and if you listen to her voice, you hear it.

But looking and painting are also something more. They do not simply point but are a manner of being responsible. That responsibility lies in Etel’s double destiny, in her co-existence with the mountain and with the team.

What is the difference between a mountain and a team or field of references? In the field of references, as we participate in culture and society, we are responsible for that freshness. We watch, we observe, we train perception, we practice the coinciding of the object and the subject. We produce talismans by training in the open-ended endeavor of sanity. This is culture when it is good. But once we die, even metaphorically, we are brought closer to the mountain. And then we are no longer responsible for that freshness but responsible to it. Talismans are made to transmit that freshness, that green, as a way of passing on the gifts of the mountain.

“Youth is that sense of depth, of space, of distance, of seeing things from always a faraway place, a past we call the future. It is this distance which shrinks, along the years, and we feel closer, more equal to the people in history, but also impoverished, abandoned by grace, moving away from the divine, that which used to be called the center.

Could a painting find that early space at least once?”12

Now that I look back on those family dinners I realize I always participated in culture and in history, and that it is made of rocks and mountains and family acquaintances. Journey to Mount Tamalpais was self-published in 1986. We are the ones who make the future.