I’ve long admired Laura Orozco — not only as a colleague and fellow curator but for the transformative work she has spearheaded at ESPAC Foundation in Mexico City. At one time ESPAC was a hub for exhibitions based on its collection that also combined generations of artists, from the Mexican modernists to young and emerging artists active in Mexico City.

Then came 2019 — a turning point for ESPAC. And just as the foundation began redefining its role, the upheaval of 2020 forced a deeper, more urgent shift. But Laura’s response wasn’t merely a reaction to the world’s chaos; it was a deliberate engagement with the evolving realities of life in Mexico City itself, allowing the exhibition space to live beyond the constrained walls of the white cube, to open artistic conversation beyond traditional exhibition practices, and to challenge the tropes within which we as professionals continue to practice. Laura has reclaimed the publication space as an alternative to exhibitions, turning the format of a book into a malleable and portable exhibition project.

Leslie Moody Castro: Can you tell us a little bit about your personal background?

Laura Orozco: I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in film in 2015, and almost a year after graduating I founded ESPAC. While creating it, I acquired a lot of knowledge regarding curating, cultural management, and mediation through many of the involved people, like Willy Kautz, Esteban King, Gabriela Correa, Alfonso Santiago, and Iraís Córdova, among others. About a year before the pandemic broke out, I began to take an interest in reflecting on art institutions, their structures, systems, and standards, mainly driven by a reflection of things I didn’t completely agree with: hierarchies according to your job title, exhibition production systems, the curator as an unquestionable authority, the forms of distribution of economic and symbolic means, and how everything seemed to be centered around exhibitions, disregarding other formats and processes. I sensed those issues were favored by outdated and colonial models of cultural production and did not respond to the urgencies and needs of our community nor the context that we were experiencing in Mexico City at that time.

LMC What does ESPAC stand for, quite literally, the actual acronym?

LO Espacio de Arte Contemporáneo (Contemporary Art Space), but now we call it Espacio(s) de Arte Contemporáneo.

LMC ESPAC originated as a collection. Can you tell us a little bit about the work, how the collection started, and what it comprises?

LO The collection began in the 1970s. Like any private collection, unaffiliated to any institution, it started with artworks that the collector was excited about and did not dwell on coherence, but rather a passion for art. Currently, the collection holds over seven hundred artworks. We own works of modern art by David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and Miguel Covarrubias. Spanning the second half of the twentieth century, Mathias Goeritz is the most prominent name. However, the vast majority of the works belong to the new art forms produced in Mexico during the 1980s and 1990s. These include artists from Los Grupos and artworks by Francis Alÿs, Taka Fernández, and Melanie Smith, among others. In recent years, the acquisitions were assessed by Willy Kautz, seeking to complement the works produced in the 1990s, as well as pieces that the collector wanted to acquire by international artists such as Daniel Buren, Jannis Kounellis, Ghada Amer, Rirkrit Tiravanija, and by emerging artists working in Mexico like Leo Marz, Christian Camacho, Chantal Peñalosa, and Ana Bidart.

LMC How did you come to be the director and curator of ESPAC? When was ESPAC founded and what was the driving force to start a foundation?

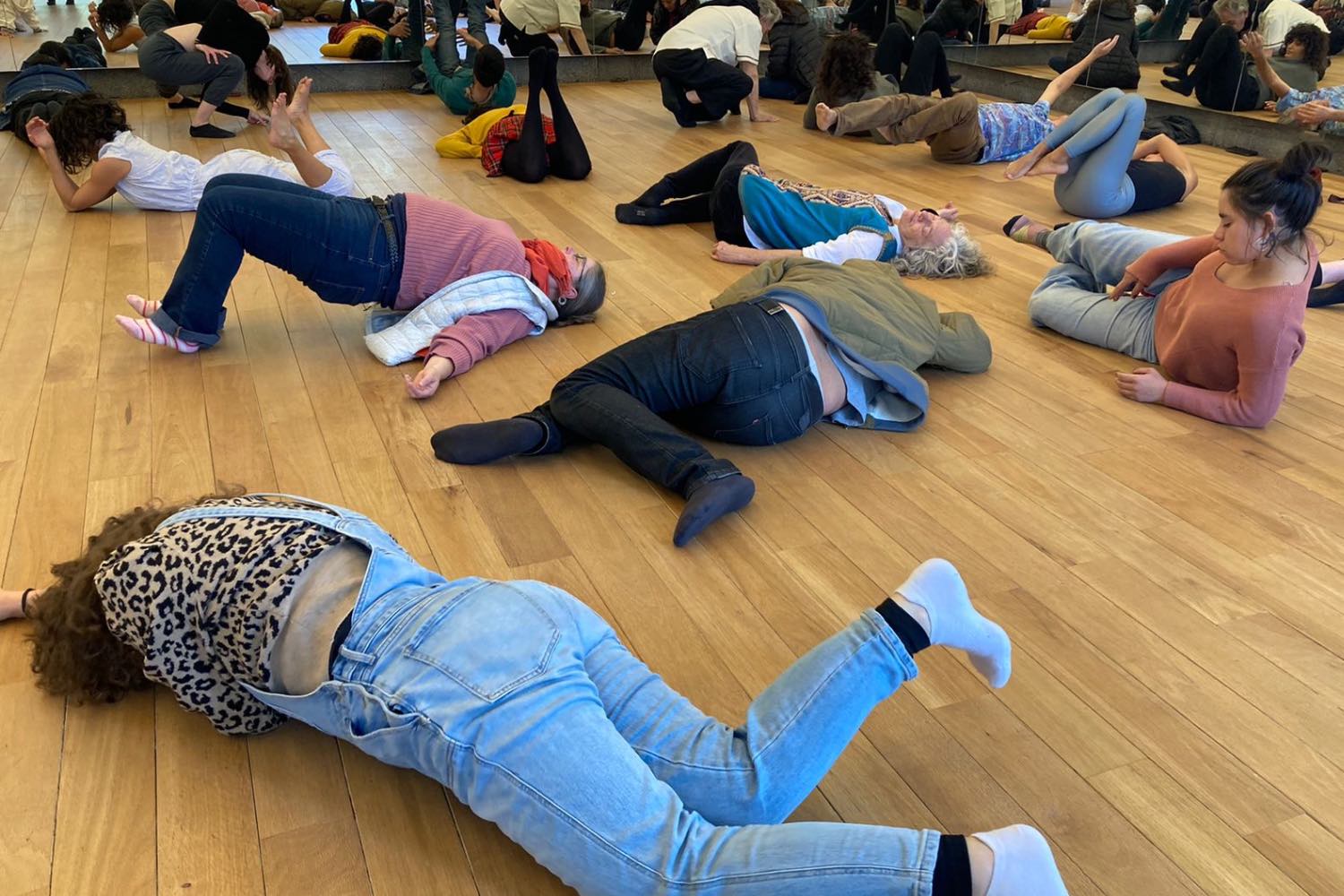

LO The owner of ESPAC’s collection first invited me to inventory, catalogue, and archive the collection. Later, he hired me to develop a project to make the collection public. I proposed creating a non-profit foundation, which became a reality by inviting specialists and establishing a clear mission. We generated a program under three lines of research: Contemporary Painting (curated by Willy Kautz), Emerging Artists (curated by Esteban King), and Audiovisual Overflows (curated by me). Each research line materialized in a specific format: exhibition, public program, and catalogue. Over time, we found it was necessary to question and go beyond the traditional notions of said formats. For example, the exhibitions could be intervened by the visitors (on one occasion, we offered everyday objects or cards with words and images to the visitors; they could place them anywhere, allowing for a rewriting of the curatorial discourse) and the public programs became the institution’s axis (and, as such, were granted their own budget, space, and time). This reversed the temporalities and uses of the white cube. On the other hand, the catalogues were not a mere document of the exhibition but challenged, expanded, and deepened the curatorial proposal.

LMC I remember the foundation started with a focus on exhibitions and, more specifically, exhibitions focused on work from the private collection. Can you tell us about the early structure and talk a little bit about how this structure has changed, evolved, and why?

LO We started with a relatively common institutional structure. By 2019, though, these systems did not make sense anymore. The pandemic helped me restructure the vocation and function of ESPAC and focus on it from a place that truly responds in terms of organization, management, structure, and program to the needs and logic of the context. In the beginning, we broke the chain of production. First, we considered the urgent topics we should address within this context and then looked for the perfect medium to engage them. We decentralized the place of the curator, and for every project, we have invited a guest curator to co-create the program with us. All the projects tend towards collective creation and dialogue. We generally commission texts, works, or actions about a specific topic to different agents from the artistic scene, starting with ESPAC’s collection and history as an institution as a starting point.

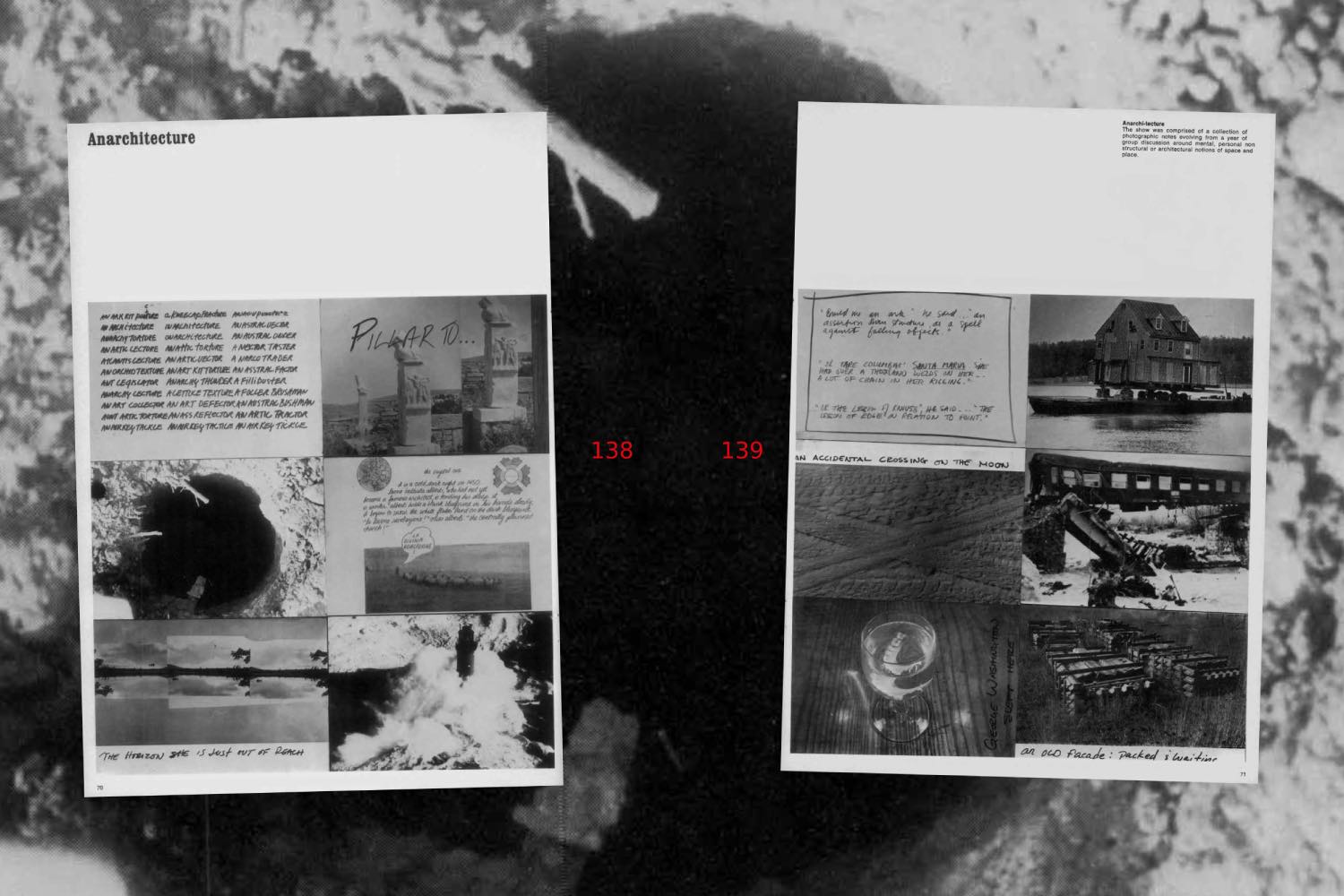

Typically, the final form of a project is a book, public program, or specific action, whether presented in an open public manner or behind closed doors. The first project based on this logic was ABCDESPAC. Published in 2021, it was a false dictionary that opens the backdoors of ESPAC. That is, we addressed the institution’s history, operation, and behind-the-scenes. At the same time, we invited over twenty people from different areas of the art milieu to pen an essay, draw an idea, or write a story to answer the following question: “According to your area of experience and own research, what do you think a non-profit institution devoted to art, like ESPAC, should be doing?”

Our latest project, Y si la casa era la institución [What if the house itself was the institution?], was a proposal co-curated with Pamela Desjardins, and it evolved over two years of sustained dialogue. The project cross-related ESPAC’s collection and the idea of the art institution with feminist theory. It encompasses twenty commissions from a variety of amazing colleagues, and concerns specific concepts and their contradictions, such as the house as the first institution, the female body as the first house, the archive as a flexible and open model for the renewal of discourses, and many other issues.

LMC How did this evolution play out with programming?

LO In terms of programming, that initial question has also shaped the content of ESPAC’s production, which is aimed towards collective creation. Projects such as ABCDESPAC or Y si la casa era la institución have been conceived under such a premise. There is also an interest in generating alternative spaces for the production and reception of art. Publishing has always held particular interest and significance in ESPAC. It gave us additional spaces to think, produce, and disseminate artistic projects. In 2018, Esteban King and Alfonso Santiago proposed the creation of an editorial series, Libros/Proyecto [Books/Project]. Artists were invited to dive into the book as a medium and engage with it as an exhibition space. They could ask a writer to contribute, but it couldn’t be a curator or an art historian. This simple exercise allowed us to discover several things. First, it unlocked the multiple possibilities of how writing can relate to art and showed us the particular methodologies of each artist when translating their practice to this particular medium. Furthermore, it proved that it was possible to generate exhibitions that aren’t bound by time and are always reproducible — and even portable. At the same time, it allowed us to create an archive of the artistic practices of a particular generation.

LMC How does this relate to your own personal curatorial practice?

LO On a personal level, however, it is in working one-on-one with artists where I have recently found great excitement. Such collaborations establish a profound correspondence that prompts a deep understanding of the artist’s practice and their needs, going beyond mere contractual work. Curatorial practice is thus transformed into an ongoing dialogue that can continue throughout the years, leading to a close collaboration that can unravel through an array of projects, questions, and problems that become deeper with time and are nourished by the attention we invest in one another.

My commitment to each project is, in other words, a long and intensive connection that demands a lot of time and energy from all parties, so I tend to choose who I work with very carefully. I truly enjoy my work; it feels like a form of reciprocity.

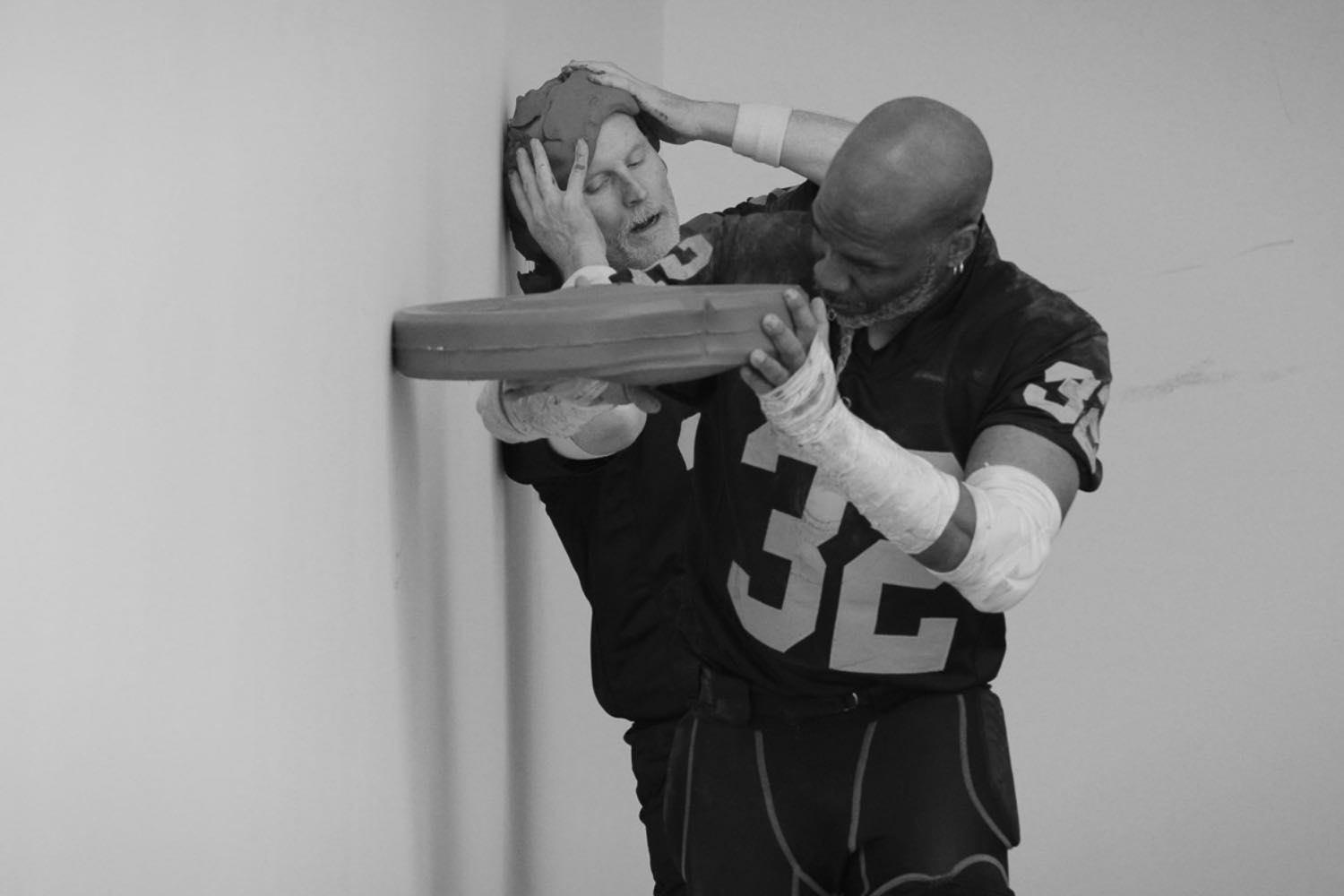

As I already stated, I am suspicious of the hegemony of exhibitions and, consequently, aside from exhibition-making, my practice encompasses the editorial field (from conceiving a publication to writing and commissioning texts) and public programming. Based on these methodologies, and with the support of feminist and queer theories, my latest research addresses topics such as rewriting history from neglected or invisibilized viewpoints, and problematizing concepts such as violence or the unwanted through various artistic practices that eschew binary models. I seek specific cases in which said aesthetics and discourses operate as revolutionary and deconstructive acts, but, above all, facilitate a discursive freedom that grants subaltern subjects the possibility to define themselves.

LMC You mentioned the “urgencies” happening in Mexico City at the time. Can you elaborate on this? What were they, and how have they changed or evolved?

LO A couple of them I already mentioned, regarding the labor and social systems in contemporary art institutions. I believe the old patterns of cultural production were forced to uncomfortably change in the last couple of years because the world also changed. Most of the curators of my generation see their work as a collaborative practice, not because of a desire or based on theory, but because working as a single entity is not sustainable in the present; you need a community that supports you in many ways. Also, matters like global warming, the feminist and queer movement finally being an open everyday problem and not just a theoretical one. Specific to Mexico City, at that time we needed to create safe spaces to simply be, talk, feel hear, learn — apparently very basic stuff, but that no institution was really addressing. ESPAC holds a very important difference to other institutions that has allowed us to behave in such a personal way, and it is because it holds a small operation and a lot of freedom in terms of discourse and resource management.