Los Angeles, November 2024

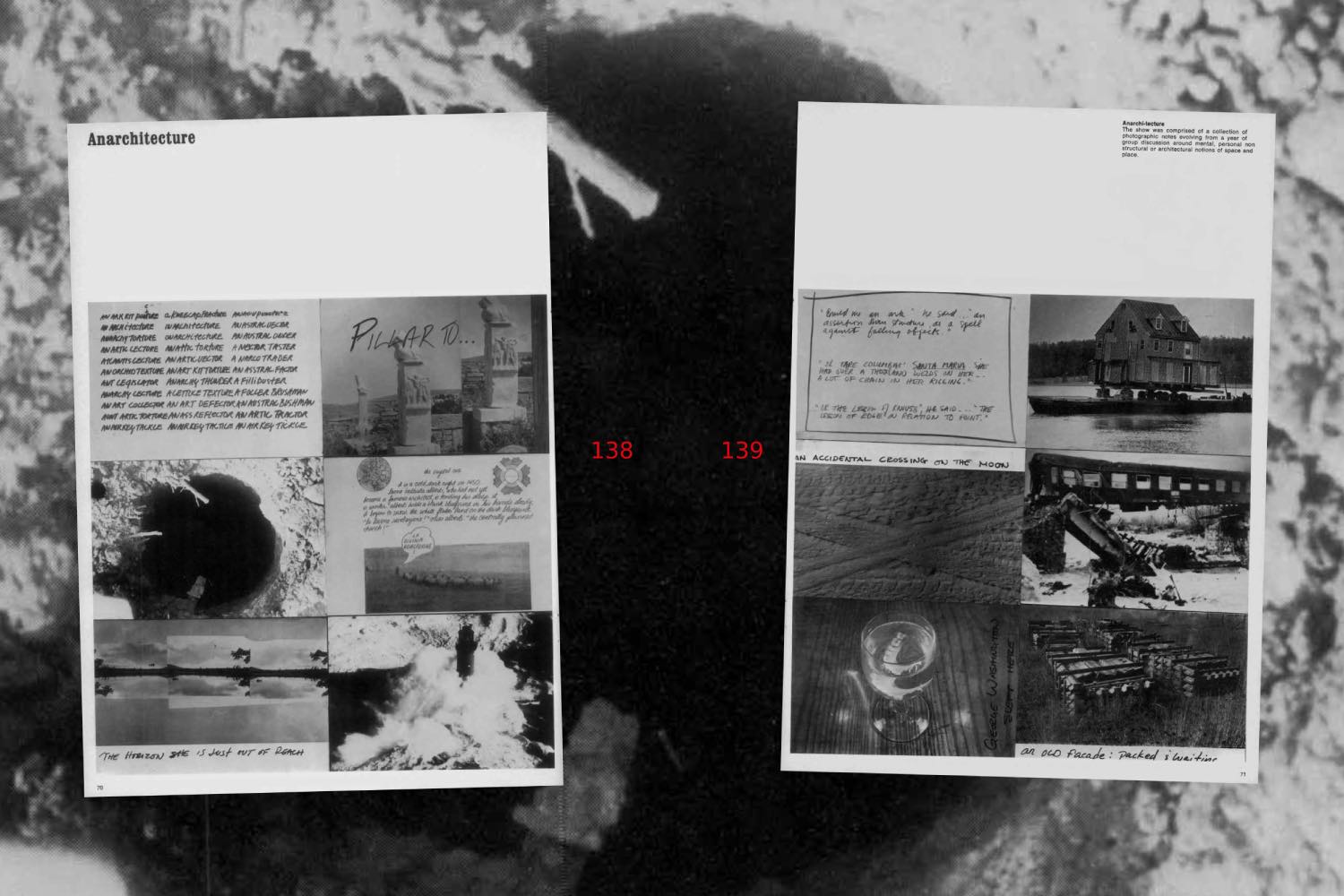

I am obsessed with the entanglement of truth and fiction. This fascination may have started without my awareness as child in the UK, watching a lot of American television and imagining what my birthplace was like. Or it could have begun when I was looking at an archive of adverts in Life magazine, and noticed sayings, gestures, and ways of life that I recognized in my everyday life. As an art student I wondered: How does racial capitalism survive so well? I came to think that one way is through ways of seeing and imagining, often brought to us through media like film and advertising. I make work where you might glimpse the gaps between truth and fiction, as well as their entanglements.

The opening credits to my new movie, Hemel (2024), linger on a moody sky over Hemel Hempstead, like the start of Val Guest’s Quatermass 2, a sci-fi film from 1957 shot in the same area. The title Hemel (short for Hemel Hempstead), in a ’50s B-movie-style font, rolls onto the screen.

Hemel is the story of my hometown, Hemel Hempstead, about twenty-four miles northwest of London. It is all true and all fiction. I was not born there but brought there as a baby by my mother, from Huntsville, Alabama. The story goes, my mum, having lived in Alabama with my dad for three years, had to bring me back to Hemel after he returned to Nigeria for an arranged marriage with another woman. She had massive suitcases of stuff and a baby. At customs, she had nothing to declare.

My story in Hemel starts with my grandmother, who moved to Hemel Hempstead after World War II as the town was being built as part of the New Towns Act to provide housing to factory workers.

As my mother states, “1955 I think she came down. She was really young, and they didn’t have anywhere to live in London. Dad got a job in a factory, he had to work there solidly and after three months they were offered a house, which was fantastic.”

Around this time in the ’50s, Quatermass 2 was being filmed in Hemel Hempstead. Meteorites fall from the sky and litter the ground of “the dip” – a grassy valley at the back of what became the council flat I grew up in. The dip served as the town’s dumping ground during its construction; people would throw all kinds of trash down there — old prams, domestic rubbish, construction waste — you name it. It all piled up to create the bed of the dip. Years later, it was covered over with soil and grass to become a picturesque park in the middle of the town. But it is now filled with camera crews and meteorites that fell from the sky. These meteorites put a spell on anyone who encounters them, turning them into workers who collect and cultivate these precious black rocks as they change state and grow into an alien entity.

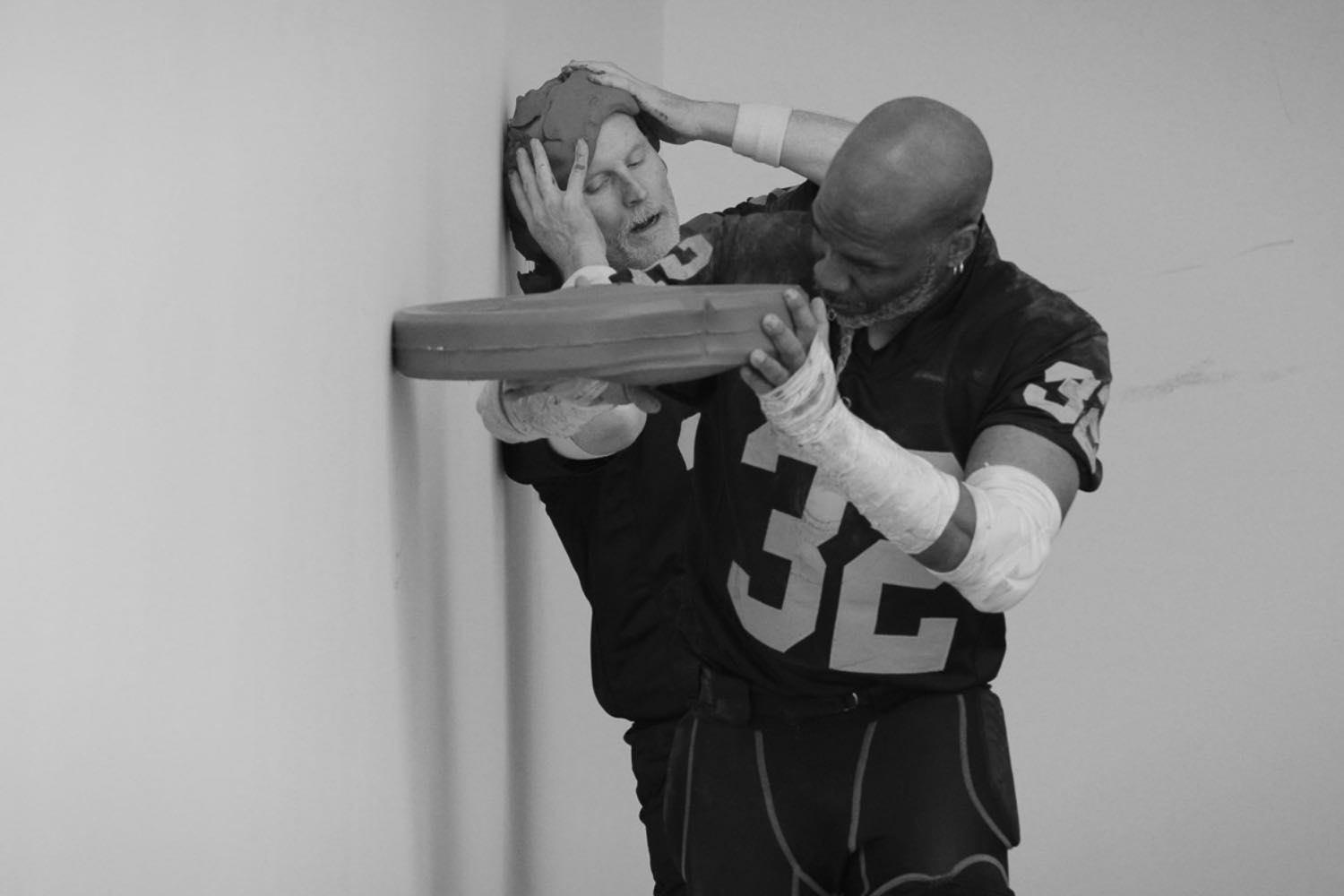

This had been going on for a while. After having left Hemel for many years to study in the US, I decided to go back and investigate what was going on in the town. I had heard about a factory, called “the corporation,” where no one could talk about what goes on inside. I tried so many different angles to speak to someone who worked there; I even stood outside the factory for hours, handing out flyers, asking them to speak to me about working conditions. No one would, until I found Harvey. Harvey, who grew up in Hemel, is also a singer in a band and was outspoken about what was happening inside the corporation. He told me that people were expected to work like zombies, that their minds were not their own anymore. And no one can talk about what happens inside.

Harvey also mentioned the racial divide in the factory, that was also present throughout the town, and suggested that the suspicion that the factory was infiltrated by an alien may have a racist undertone. Ever since Hemel was first built, it was envisioned as a utopia for white people. As years went by, the town has suffered from economic neglect, factories and shops closing, Brexit-related issues, and people losing work, leading them to blame outsiders. People are nostalgic for the Hemel that is only a myth. Hemel, like much of the modern West, is built on diversity and the extraction of people and resources from the “Dark Continent.”

My investigation took me to the local shops, where a woman told me that Hemel used to be a nice place, but people coming here who don’t belong have ruined it. This statement hit me hard, reminding me of how I never felt I belonged in Hemel, or even in my own white, working-class family. I recall different scenarios when my just walking down the street was met with disapproving glances and questions of why I was there.

I decided to bring one of the black meteorites to my mum’s house. We sit in the living room — my cousin, my uncle, my mum, and I — silently passing the rock among ourselves, handling it with care. We hold space for the difficulty this rock represents, feeling its weight in the complexity of this moment being captured on camera. The rock has possessed us, brought us together and miles apart at the same time.

I meet Stan, who also worked at the corporation for a while. He came to Hemel from Nigeria, joining his family after his wife took a job as an assistant in an old peoples’ home. An entrepreneur in Nigeria who ran a hotel and a food TV program, he could not find similar work in the UK and ended up working at the corporation. He was treated as an alien in the factory and the town where his children are growing up.

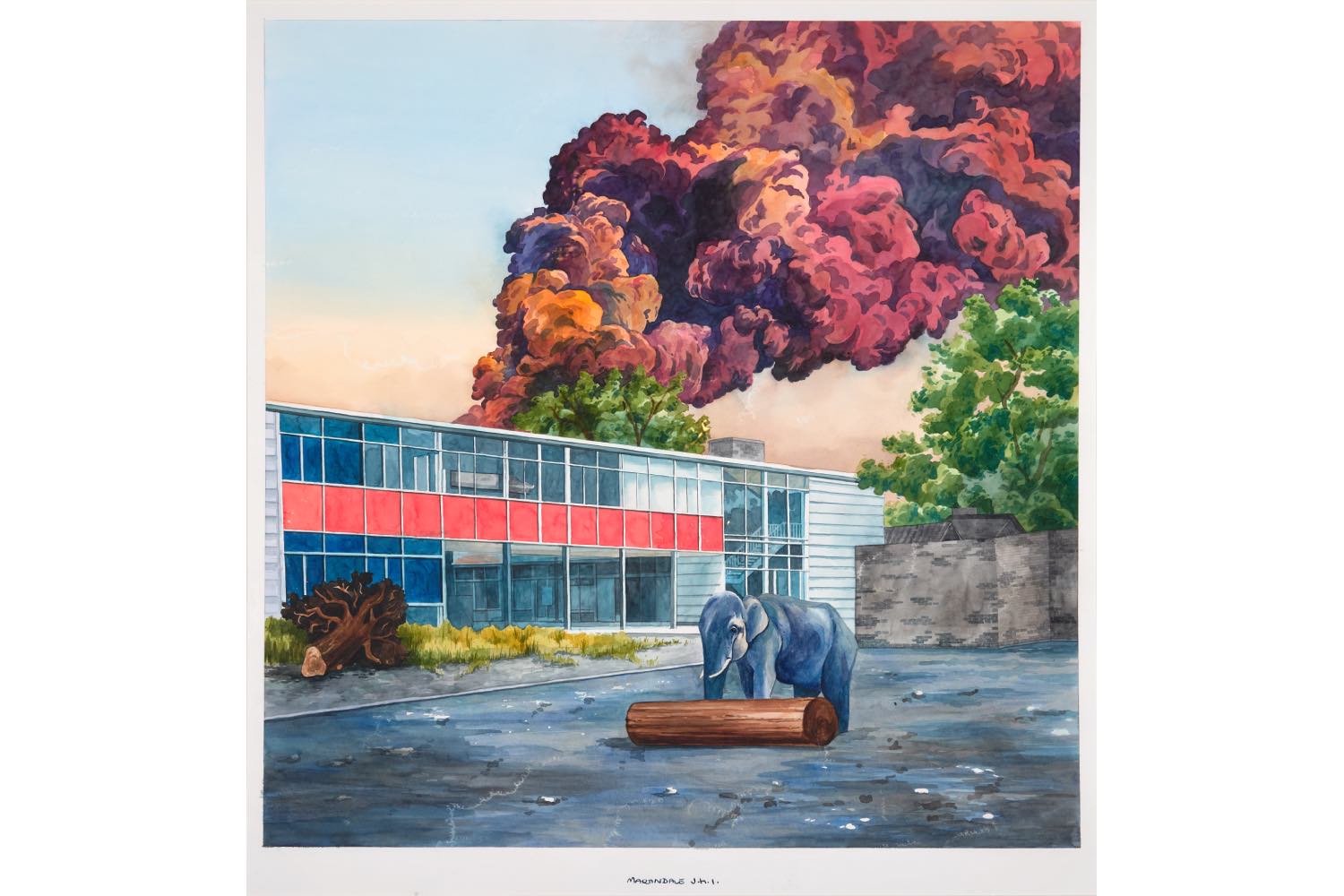

This had all been going on for decades but really came to a head on December 11th, 2005, when the alien entity tried to escape out of the factory in a massive explosion, threatening to destroy the town. Known as the Buncefield explosion, it was fortunate that it happened on a Sunday when no one was working. There were no fatalities, but the explosion was so large that it could be seen in France. Worthy of a film ending. But life in Hemel continues as it always has.

The credits roll down the screen. There is no sound, or just the sound of a quiet night.