In past interviews, Emily Mae Smith has described her current style and aesthetic as a result of her own experiences with the oppressive conditions of art labor, which led to the realization of her own marginalization due to gender and class as a female worker. Touching on intersectional feminist issues, but in a manner that does not allow for facile arguments or conclusions, she relies on her technical maturity to compose narratives emerging from her own circumstances as well as excavations of Western art history, repeatedly employing symbolical figurations such as brooms, fruit, teeth, mouths, and female breasts. With this idiosyncratic visual language, her solo exhibition “Avalon” arrays metaphorical layers of a fictional paradise that is nevertheless infused with the smell of, as she puts it, “corruption.” The allusive contrast is illuminated colorfully and comically as a condition informed by capitalist desires and the colonial unconscious within art history, opening up spaces for counteractions to emerge and be negotiated. A small painting with of same title from 2019 represents a barren yet tender desert landscape onto which female bodies are projected under the dim moonlight, unveiling the invisible female bodies that were once located within patriarchal and colonial territory. Instead of reproducing images of traditional female bodies, her brooms — animated characters inspired by Disney’s Fantasia — are playfully cast off the role assigned to women in art history: as primitive tool, domestic labor, and (sexual) object. Gleaner Odalisque (2019) transforms the commodified female body into a faceless broom, which turns backward and gazes into the dark. Other paintings imply more specific frictions between narratives, ranging from myths of seduction to metaphors of globalist exploitation. They juxtapose images of contrasting textures, for instance between industrial material and human bodies, connoting violence and greed as well as the masculinity subtly symbolized by phallic allusions, all the while suggesting a potential (female) inclination undermining these cultural tropes. Mixing various visual and sensual influences, including illusionism and Imagism, her works embody a composite of subversive ethos that is built on resistance to today’s social and political landscapes and the histories that have produced them.

7 November 2019, 4:10 pm CET

Emily Mae Smith Galerie Perrotin / Tokyo by Mika Maruyama

by Mika Maruyama November 7, 2019Jimmy Robert: Reworking Performativity

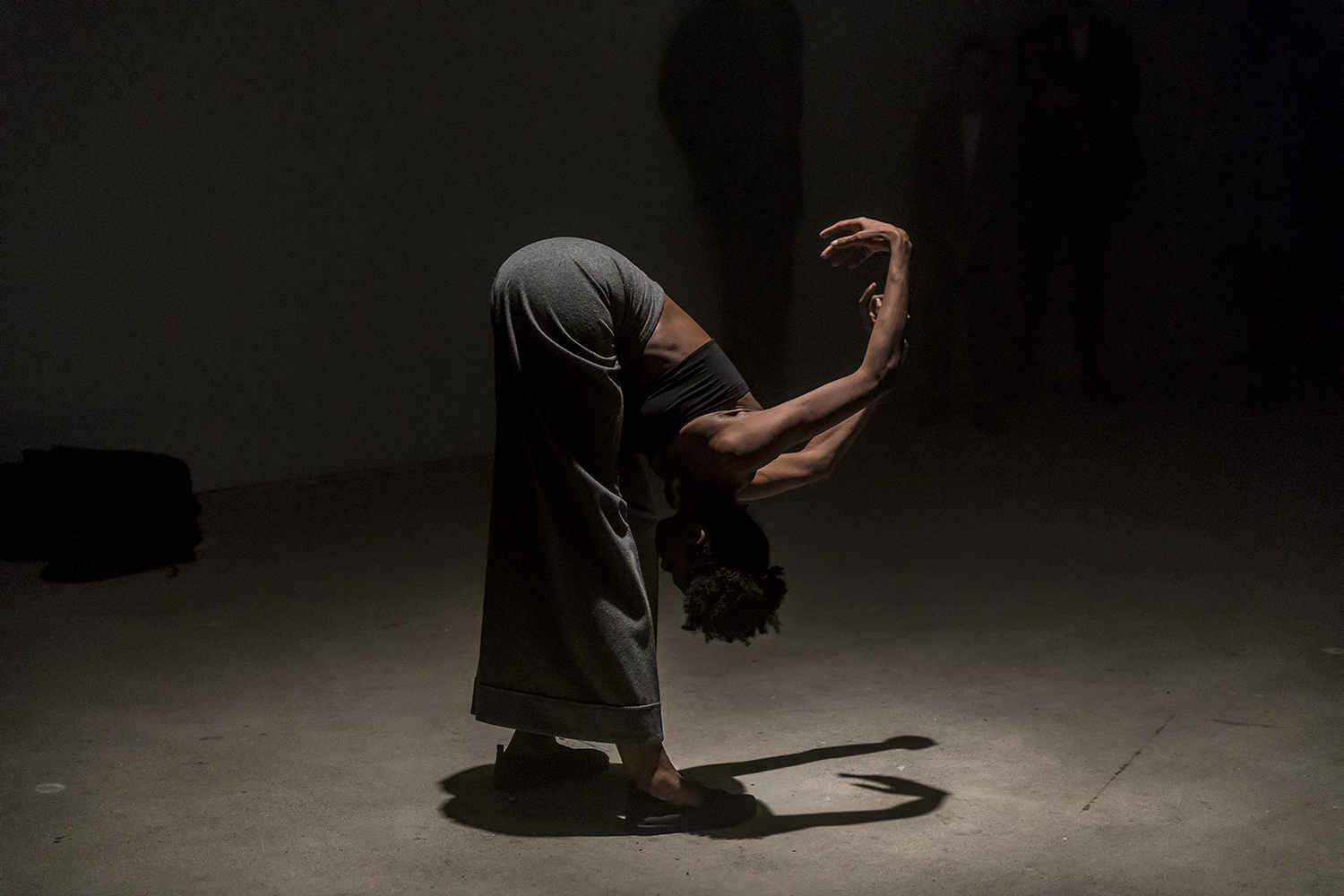

The work of Berlin-based artist Jimmy Robert (b. Guadeloupe (FR) 1975) is situated in the interstices between the art object,…

Are You a Feminist? Anne Bean (2014) in conversation with Anne Bean (1973)

Are You a Feminist? Anne Bean (2014) in conversation with Anne Bean (1973) In 2014, at Matts Gallery, I performed…

Marta Minujín’s The Parthenon of Books: A Living Elevation of Social and Cultural Relations

A collective endeavor of Greek antiquity — no less than eighty different artists worked on the frieze alone — the…

Elaine Cameron-Weir JTT / New York

In Elaine Cameron-Weir’s “strings that show the wind,” three sets of paired sculptures stand, as if halted mid-procession, atop an…