Eleonora Milani: Let’s start from the beginning. How did you start dancing and become a choreographer? Has it been a natural transition to performance art?

Cecilia Bengolea: When I was a child I dreamed about becoming a dancer. I started feeling more self-aware when I was twelve, and I took jazz dance lessons. Later I studied with a dancer from Argentina, Guillermo Angelelli, from the Odin Teatret company in Denmark. The dancers from this collective research different archaic ritual dances from South America and Asia. I learned “the dance from the wind” from the Altiplano in Bolivia — hyperventilating. This dance is necessary in the Bolivian high plains because they don’t have much oxygen at three thousand meters above sea level. But in Buenos Aires, there is no altitude like in La Paz, so we were hyperventilating. We attained high states of mind — a different kind of consciousness. At seventeen years old, this dance made me realize: there is not only show dance, there is also a deeper ritual dance. Street jazz, dancing in clubs, and anthropological dance were my formation, I’m not an academic dancer, I consider myself an experimental dancer, autodidact.

EM: This transfer from one state to another is an interesting aspect of your work. It makes me think about the relationship between performance and sculpture. In your performative works, you integrate the body and movement with a sort of objectivization; your idea of movement and the elements within the body, as well as the relationship with outside space (nature), are an index of this feeble dualism between sculpture and performance. Tell me about how you see the relationship between object and subject.

CB: Speculating with multiple perspectives from subject to object is at the core of my practice. I went for one year to dance school in Europe, at that moment I also started working in a strip clubs to pay for school. Becoming objectified by the situation of exciting the viewer in a very codified way gave me distance of my own self and allowed me to enjoy this new perspective. I thought I could augmentate some capacities to fit into this specific category of object for that context and situation. I am fascinated by this thought of actualizing our capacities of composition and also our affects without judging ourselves. This is contained very much in Spinoza’s Ethics — a book that I always re-read, because I think of this situation where he says that we can have more resources, a greater capacity for acting, if we actualize our composition with others.

EM: Nobody ever thinks of the club in that way — in terms of the “composition” of a precise place. I mean, the first image you have of the club is a promiscuous space, with a darkness that reveals, in a certain sense, forbidden forms. But in the end we start right from there, that darkness. The club lights actually build a scenography, a precise architecture of meaning, which must refer to an aesthetic of desire that is generated from the display. A strongly objectified place that in turn objectifies.

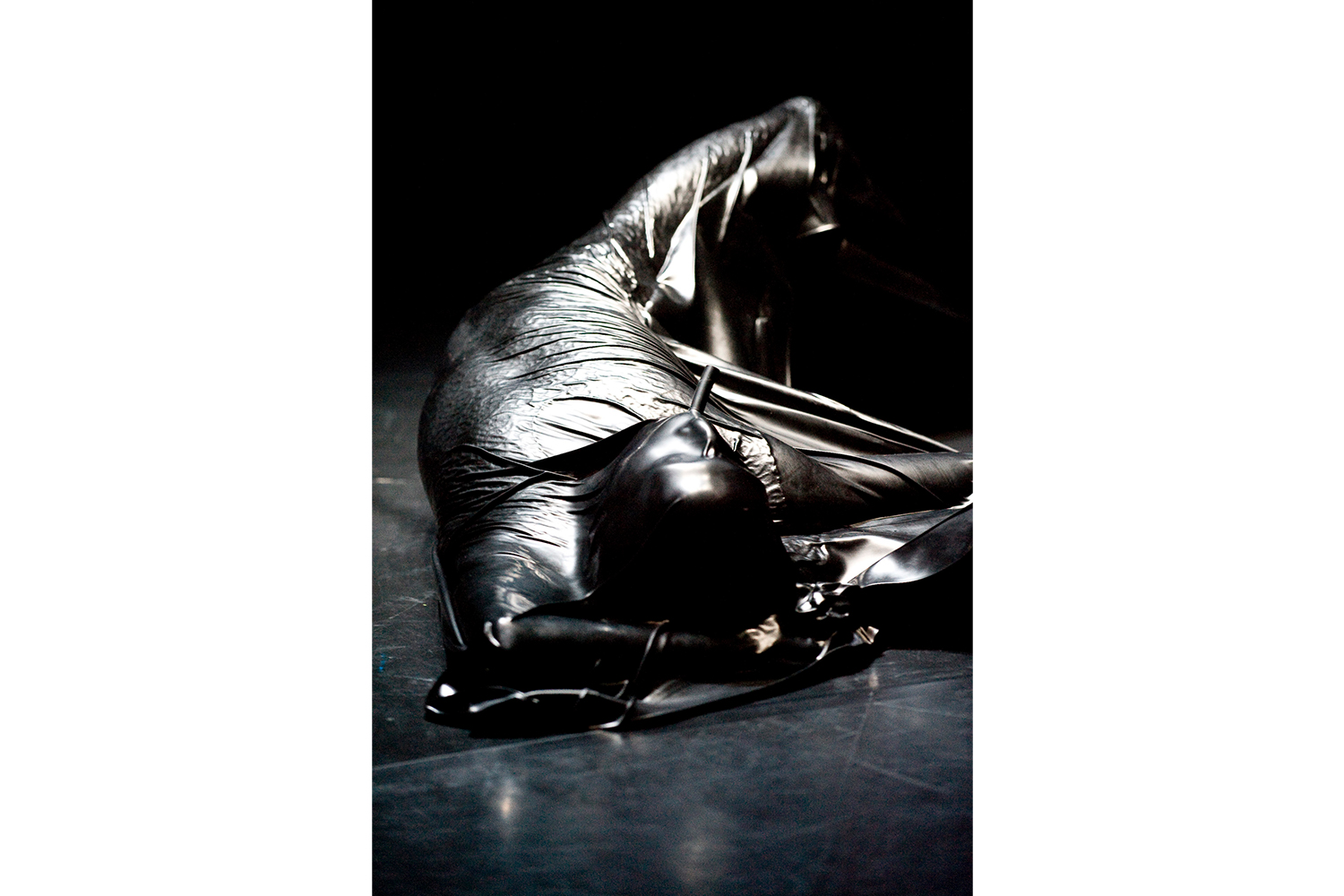

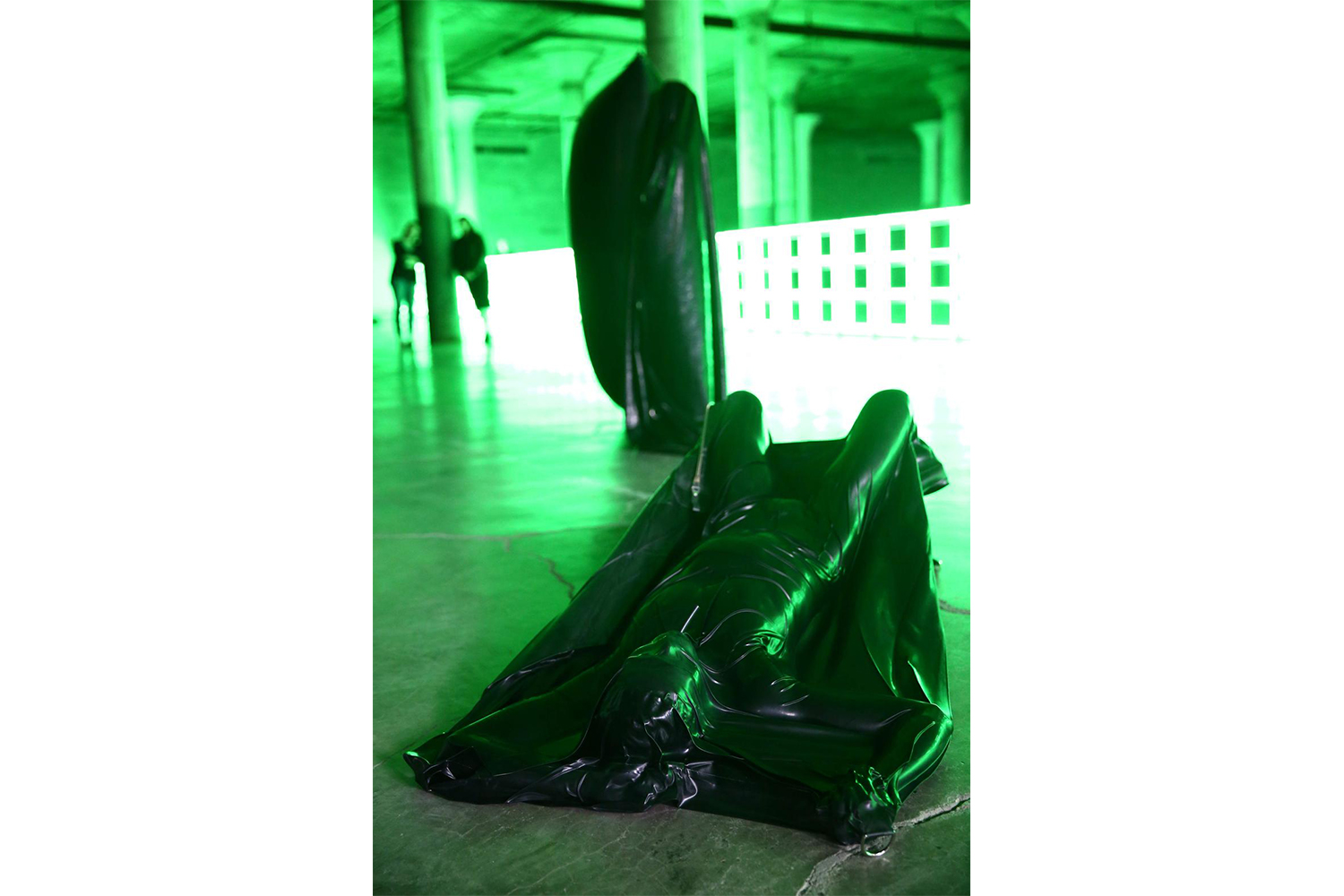

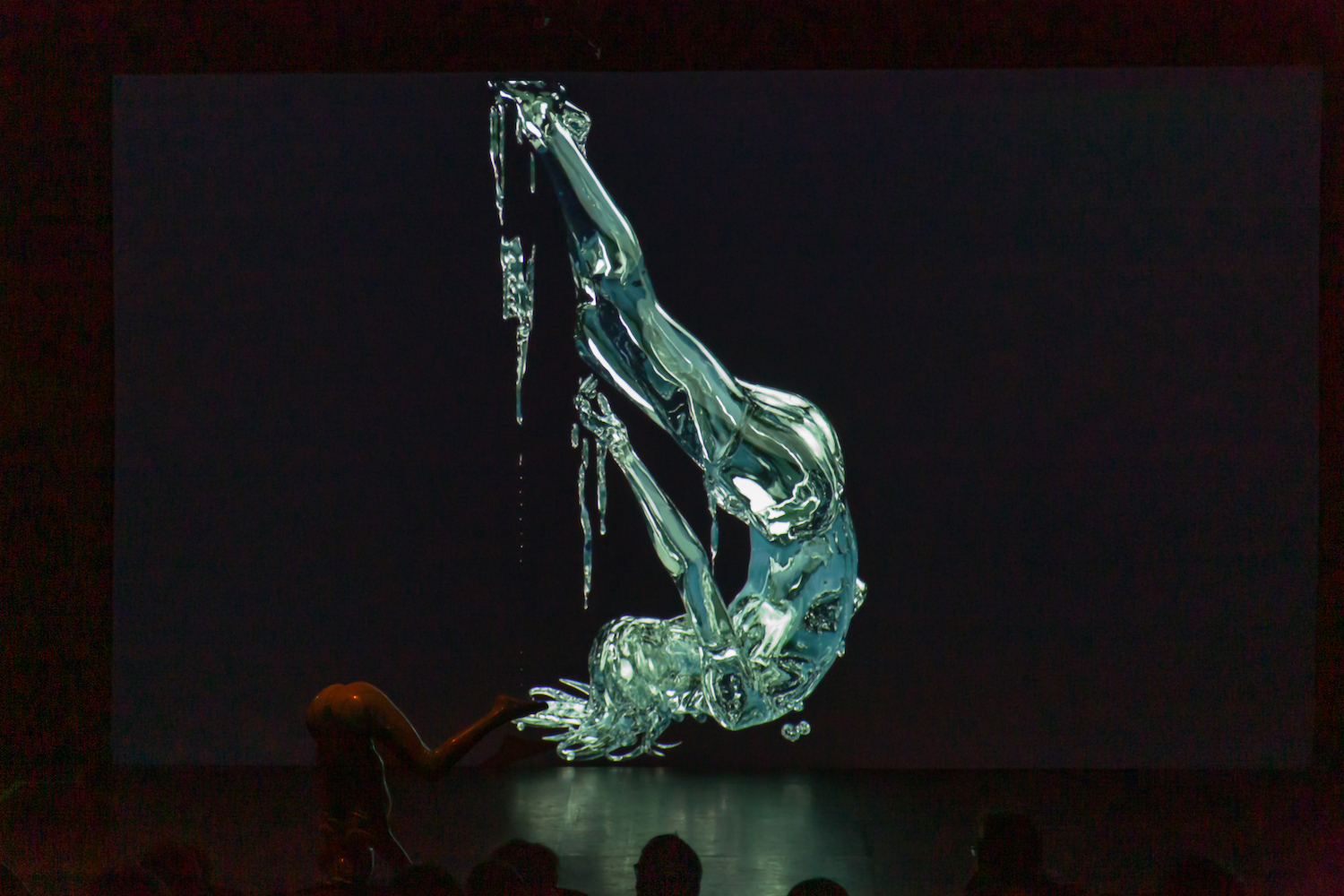

CB: In the strip club, it was clear that we had to compose ourselves with the club, with the clients, with the other dancers, to become something else with another perspective. I thought there was a power for women in this. I also had to be very clever to be happy about this objectification of myself. To not judge myself, to not feel like I was a stagnate object. Then I met some girls working in an erotic theater who were making unconventional performances in which they would take things out of their body like plastic cockroaches or things that were not allowed in the classic club where I worked. They were going further in the invention of themselves. In 2009 we practiced a performance with my longtime collaborator François Chaignaud, inspired by the mythology of the sylphs, Sylphides (2009), in which we were going inside latex vacuum bags where our senses where deprived. This performance changed our perspective radically, letting us become animated. More abstract than a figurative body can be. In this performance we’re always depicting something other than our body, even if it’s hard for a human body to be abstract.

EM: Yes, I have seen Sylphides, though not live, and this leads to an even more interesting level of objectification. This piece is like a funeral rite with these amphidromous, unearthly beings. Sylphs are creatures that question the materiality of the body and the afterlife, as well as our relationship with time, dualism… Reincarnation could be seen as an example of this changing of states we were talking about.

CB: In dance we practice to have several perspectives at once — being seen, acting, interacting, and seeing someone else who brings something in. What brings in these different layers of consciousness is thinking of oneself as something other than a subject. I think of my sculptures as characters or friends, or company, someone to have a dialogue with.

EM: Composition is certainly a fundamental aspect in your performances. Does the way you renegotiate the relationship between sculpture and movement have to do with your evolution in thinking of body-objects as elements? Lately I was re-watching Merce Cunningham’s performances from the ’60s and ’70s. I found a sort of parallel to your attitude about conceiving of objects and people on stage, not in terms of movement or the use of the body — because, of course, it’s more conceptual, more abstract, and more geometrical than yours — but in terms of composition. I found an interesting connection in terms of the use of objects, scenography. I perceived a resemblance in how you make people act, dance, and animate objects. The way dancers interact with elements in those pieces is kind of curious. For example, RainForest (1968), staged for the first time in Buffalo — Andy Warhol made the set and Jasper Johns did the costumes — reminds me of your way of connecting human/object and subject. It’s really amazing how elements are part of movement and activate a sort of animistic vision of everything. What do you think about it?

CB: What I love about Merce Cunningham’s philosophy is that he is absolutely modern in the way he frees dance from meaning and takes away the subordination of dance to music. He doesn’t allow the dancers to listen to the music they will perform with until the day of the show. He doesn’t show them the scenography either. I’m inspired by his unique perspective of seeing dance for what it is, and not trying to use it for narration or as a tool to conduct emotions. He comes after Martha Graham, who is the master of storytelling and emotions conveyed by dance. He is the first one to put dance at the level of art, self-sufficient, not in service to any other art. His piece RainForest can relate to our piece Sylphides. We made these latex bags, and we also go through all these material states, changing from being an inflated bag to being a sculpture like a sylph or some marble drapery sculpture, also becoming amorphous. I had never made the connection with the piece by Cunningham. When we did Sylphides, I hadn’t seen this piece. I think about Olafur Eliasson’s water sculptures. Dancing fountains.

EM: I know what you are referring to. I saw his Big Bang Fountain (2014), installed at the Tate Modern in 2019, in that incredible exhibition “In Real Life.” It was terrific. It’s moving, performing water. Totally. I perfectly understand what you mean because I’ve been a dancer and I have the same feeling about elements that evoke movement. Your interest in elements makes me think about the ’60s and this return to the elements, water, fire, air, earth. And it’s curious because at that time this connection with the elements was about connecting art to life. It wasn’t in the direction of a non-anthropocentric vision; it was still always about art and about how to make it, but humanity was still at the core. There wasn’t a need to go toward a nonbinary world — it was really far from that. Of course, your interest in elements is more closely aligned with a nonbinary world, and I think that’s the way you treat elements and objects. And sculpture, the body as sculpture. It’s a sort of declaration of a nonbinary existence. I’m thinking of Danse au fond de la Mer (2019), a repertory of utopic dance compositions inspired by French choreographer François Malkovsky. He conceived these dances to create a movement that highlighted the disharmony between man and nature caused by the industrial revolution, with the aim of restoring harmony between man and nature again.

CB: At that time the meaning was more symbolic than about allowing the element be what it is. In the early nineteenth century the Monte Verità group (1890–1920) aspired to be in harmony with nature and practiced a return to nature, greeting the sun god, natural food, nudism — a sort of pagan and communist community. There was also Malkovsky, who followed Isadora Duncan’s thoughts about dance.

EM: Lately while I was re-watching Cunningham’s works I looked at ballet and dance from the 1930s and ’40s. There’s a huge body of literature about the relationship between humans and nature. It was about showing a kind of hybridization between nature and humans. However, from a solely formal point of view, or in a theatrical sense, it was about customization — in lots of pieces dancers wear protuberances to look like animals. So I thought about some of your works like Mosquito Net, Dance for dead fishes and friends, as well as Dancehall Weather, Tryptique (all works 2019), and Synchronized Serpent (2020). What’s the origin of your interest in hybridizing humankind? When did you start thinking that it was possible to explore this within performance art — this hybridization of humans and nature and other creatures?

CB: When I was younger, I had asthma and I couldn’t run. I had a little pony since I was three years old, called Flor. I galloped everywhere from the age of three. I learned on my own, and I fell many times. I love to run. So I always thought hybridization was possible through this bond; it was a magical moment of movement and a speed that I couldn’t reach myself through running. It was my first hybrid dance. The centaur dance. Horses are very important in Argentinian nature culture and mythology. I’m always astonished the kindness and patience of horses, allowing us to be carried on their backs. There’s an interesting dialogue between horses and humans throughout history. Now I’m filming a girl who rides in the south of France without saddle nor bridels . She communicates with her mare and has constant dialogues with her.

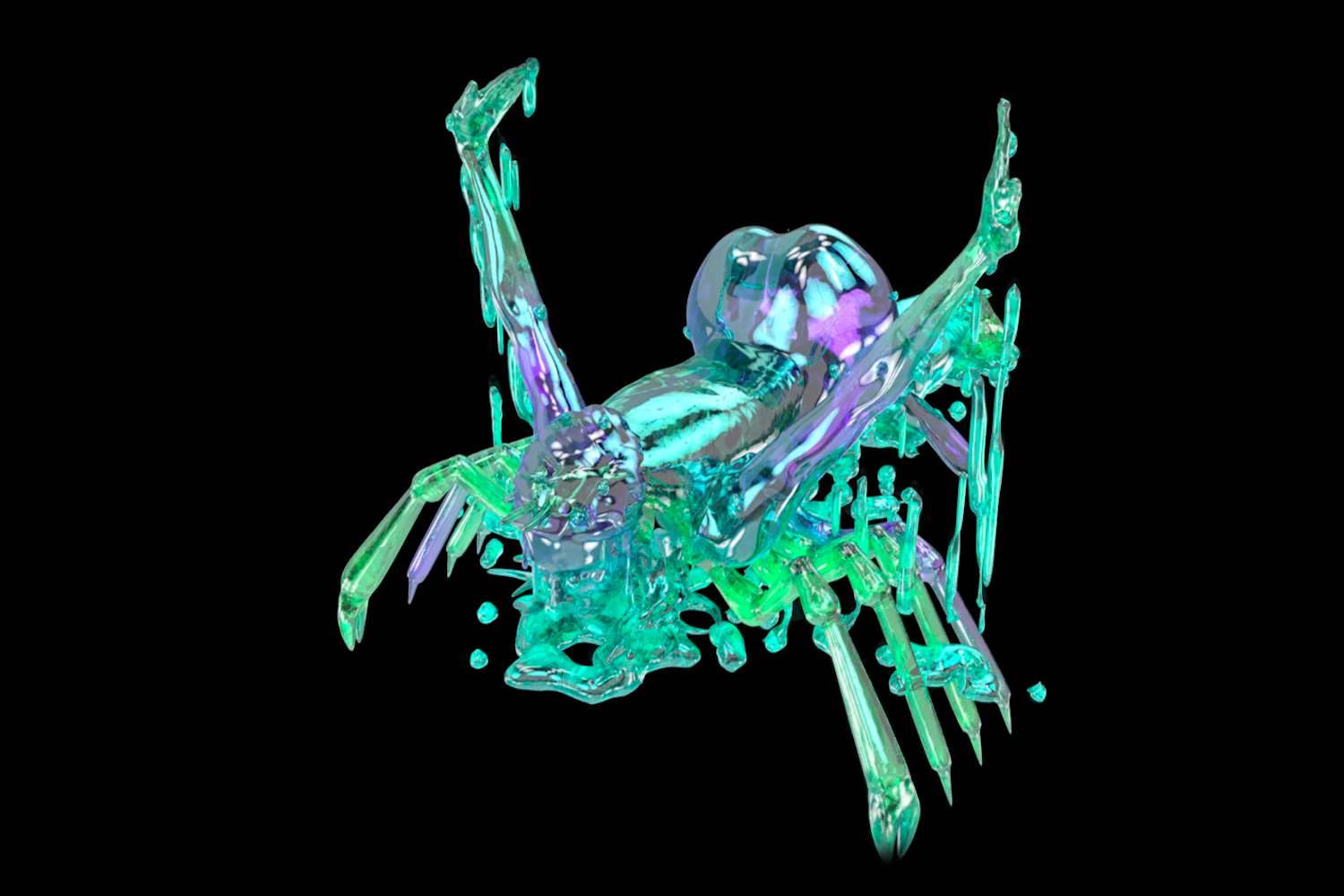

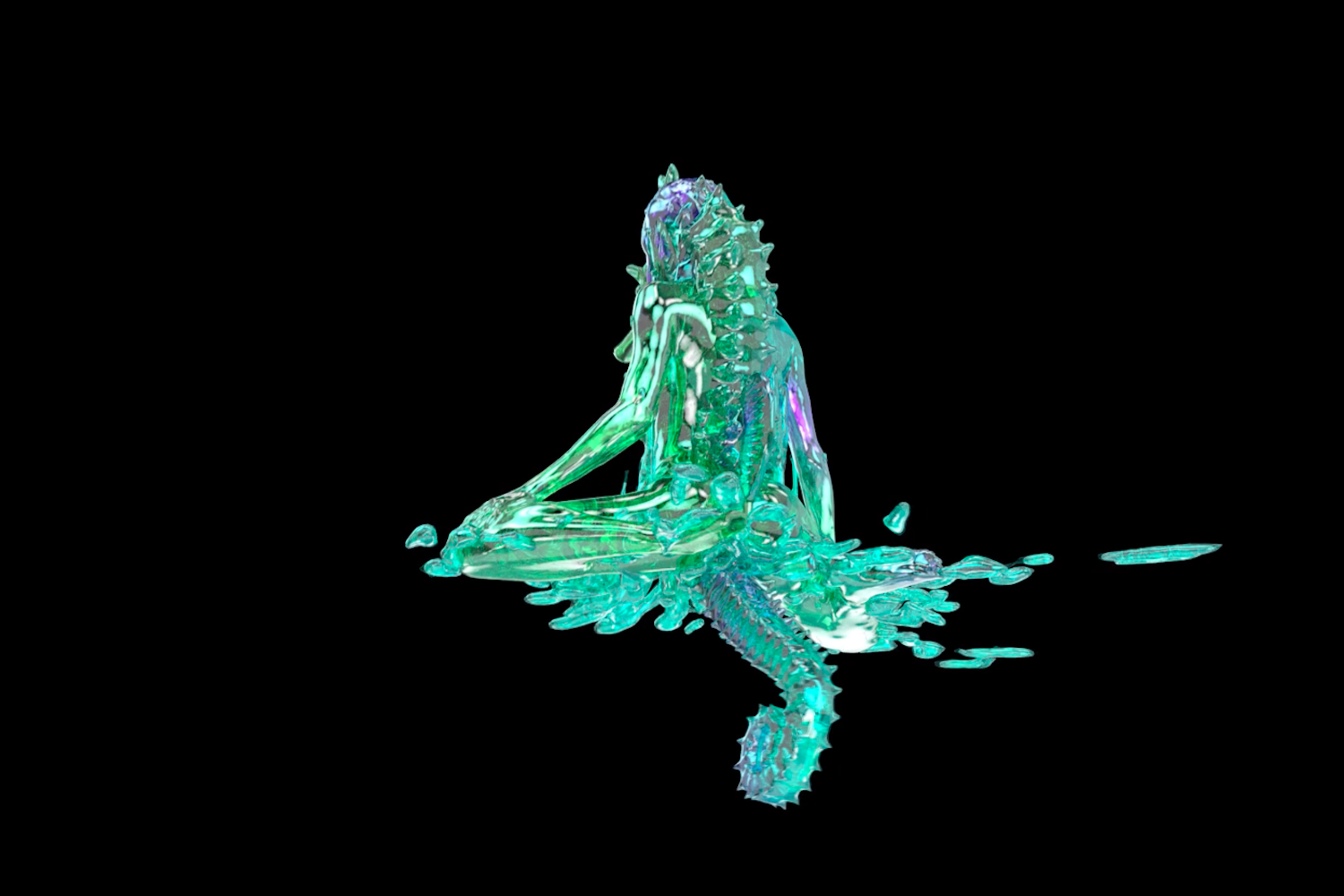

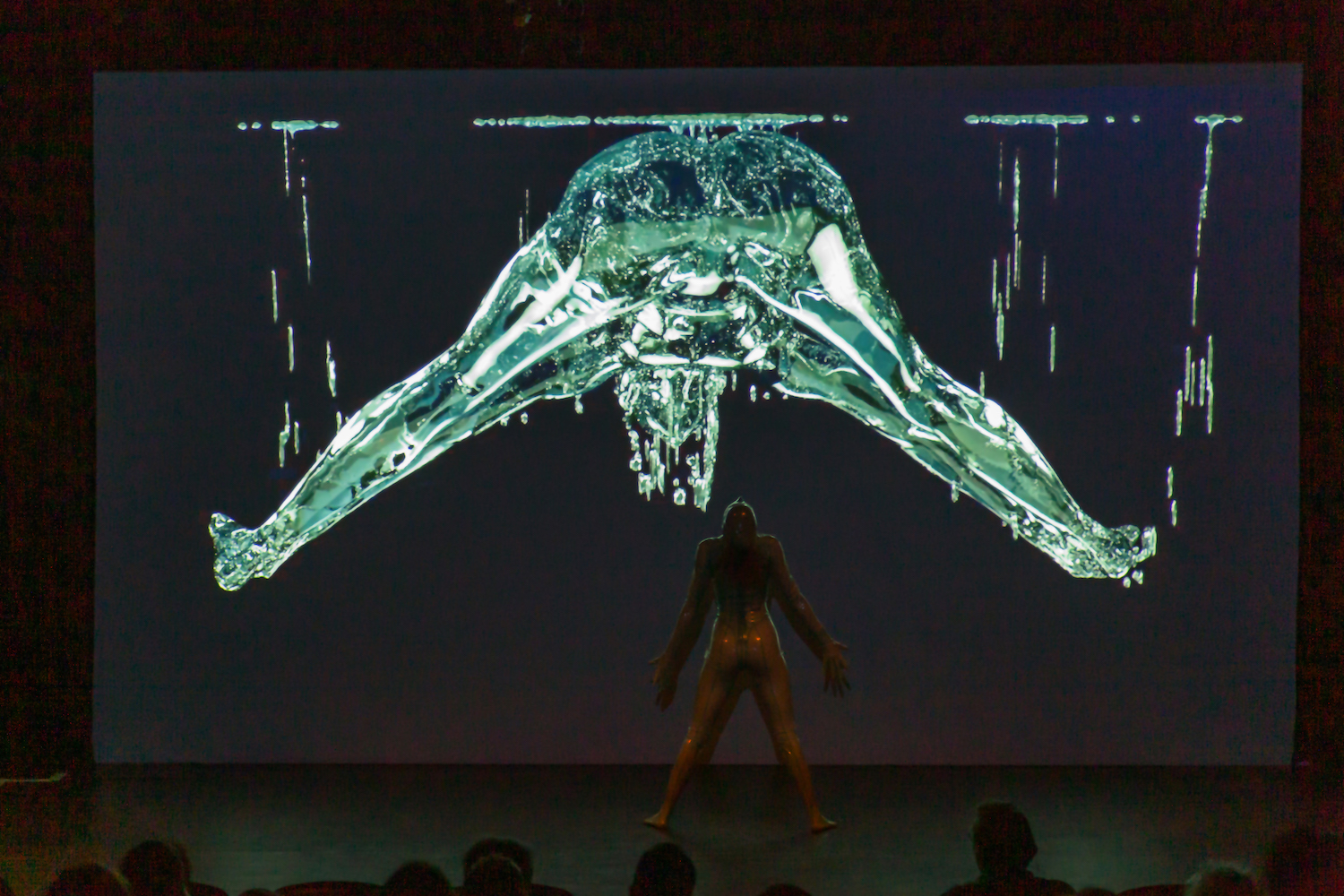

EM: You also developed a constant dialogue with your own body, as in Bestiaire (2019), in which you literally hybridize yourself, scanning your body in different positions and turning the 3-D video into an animated bestiary; or in Favorite Positions (2018), inspired by the mind of the octopus, which suggests a body without boundaries. Your body is your first medium, your primary element, and it becomes a social tool, as we can see in your dancehall experiments. I’m referring to video works such as Dancehall Weather (2017), Lighting Dance (2018), Shelly Belly Inna Real Life, and Tryptique – Oneness (both 2020). Can you tell me more about your relationship with Jamaica?

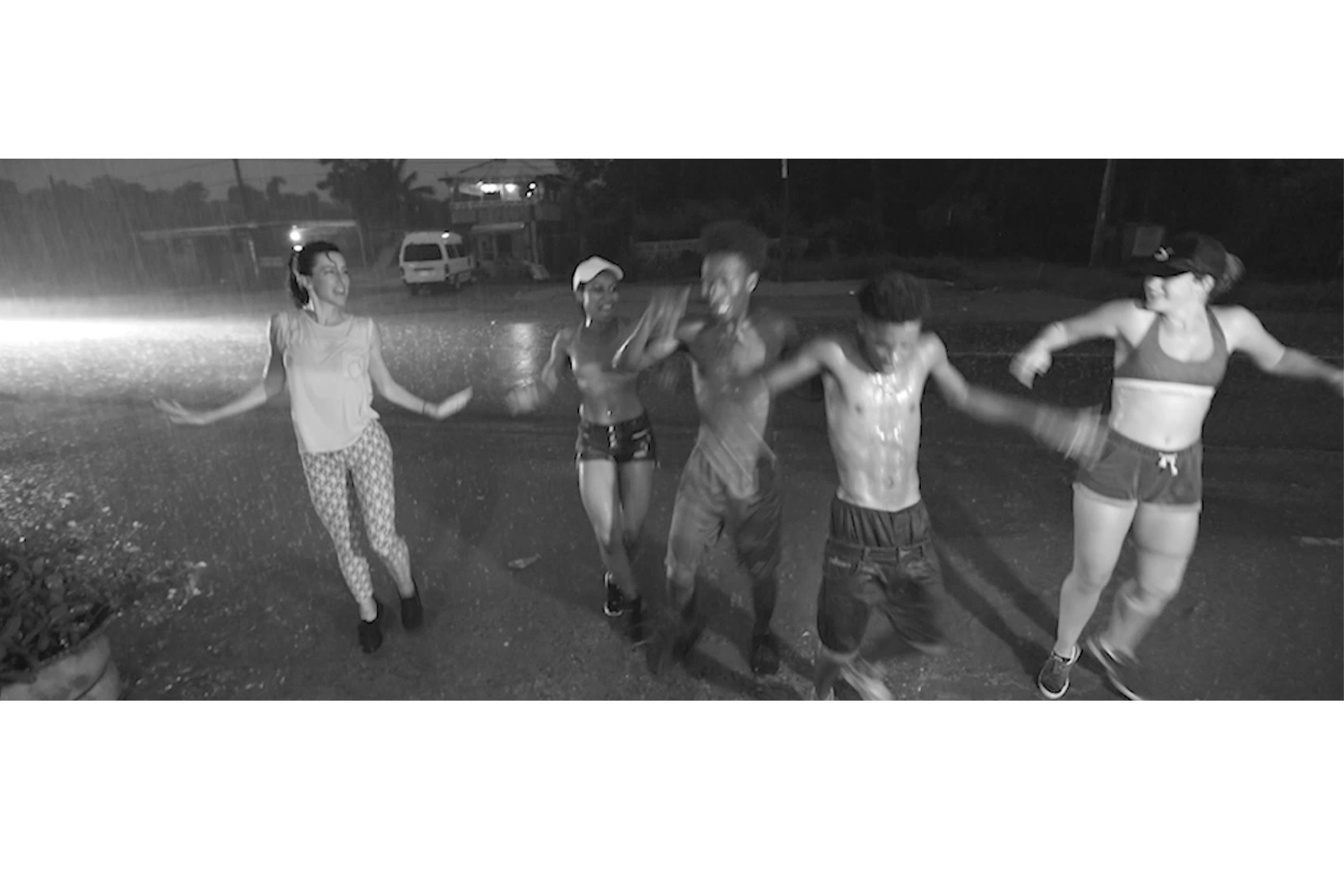

CB: The dancers I met in Jamaica practice the pagan-sacred ritual of the sound-system party as a kind of religion. It is a system for getting together, to share this community of movements and ideas. It’s a way of communicating very deeply across different levels celebrating death and life. It feels like home when we go there; dancers from everywhere are welcome. If you go and you want to learn for the first time, like I did in 2014 — I didn’t know anyone — the community is very inclusive. We organize parties in Europe with the dancers from Jamaica who have moved to Europe. We just recently made one in La Casa Encendida in Madrid. It is important to question cultural appropriation from countries that have been subjugated throughout history. In the case of Jamaican dancehall, the culture wants to become global through media, to spread, and more and more dancers make these movements everywhere. Only dancers from Jamaica can invent dancehall steps, but everyone can reenact them to spread the spirit. It is an infinite library of steps, like Babel.

EM: It’s interesting the way they build national values through dancing — it’s restrictive in a sense. What other countries have you experienced?

CB: There is a collective knowledge and intelligence — jokes and humor are shared through movement. In Cuba it is a different situation than in Jamaica. Both islands are very close to each other. They have almost the same weather. I like to think that as the nervous system is electric, water, humidity, or sweat can propagate the electrical conduits of the nervous system. Due to humid weather in the Caribbean, the neural system inhabits the whole body, like an octopus, a non-centralized intelligence. Every part of the body has a specific intelligence. This allows one to produce more complicated rhythms in different directions at once. In Cuba, the colonies created a lot of institutions and buildings which brought dancers into academic situations. They attend the conservatory, and then they work in a modern dance company or in a ballet. They always rehearse and practice inside buildings. I made up a piece for the company Malpaso in La Habana. This company reminded me that they are not allowed to dance outside in relationship to the weather, to the rain and the elements. They dance inside the building, inside the theater. They study Horton, Limón, ballet. The regime doesn’t allow them to dance in the streets in relation to nature and the elements, like in Jamaica.

EM: The Cuban classical technique is just amazing. They can turn and they use their arms wonderfully. When I studied at the Opera Theater in Rome I experienced a bit of Cuban technique. It’s like they insert a movement into the technique, a breath, a rhythm, and you feel immediately that is far from the Vaganova method. I’m so in love with Cuban technique, but I didn’t know about this “confinement” of the dancers.

CB: Circulation is certainly not very dynamic or free in Cuba. In Jamaica, amazing dancers can study ballet and become as technical as the Cubans. But they love to dance in the street, on concrete, near the highway with the energy of the cars passing, moving with the energy of the eagles, the wind, the storm, the sun and the rain. And they keep on dancing, even if it starts raining. Everybody stays in the party. And it’s unique because all the parties and rehearsals are outside because there are no institutions. There is only one school of dance in the whole of Jamaica, in Kingston, downtown.

EM: Can you talk about your forthcoming show “Animations in Water” at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao?

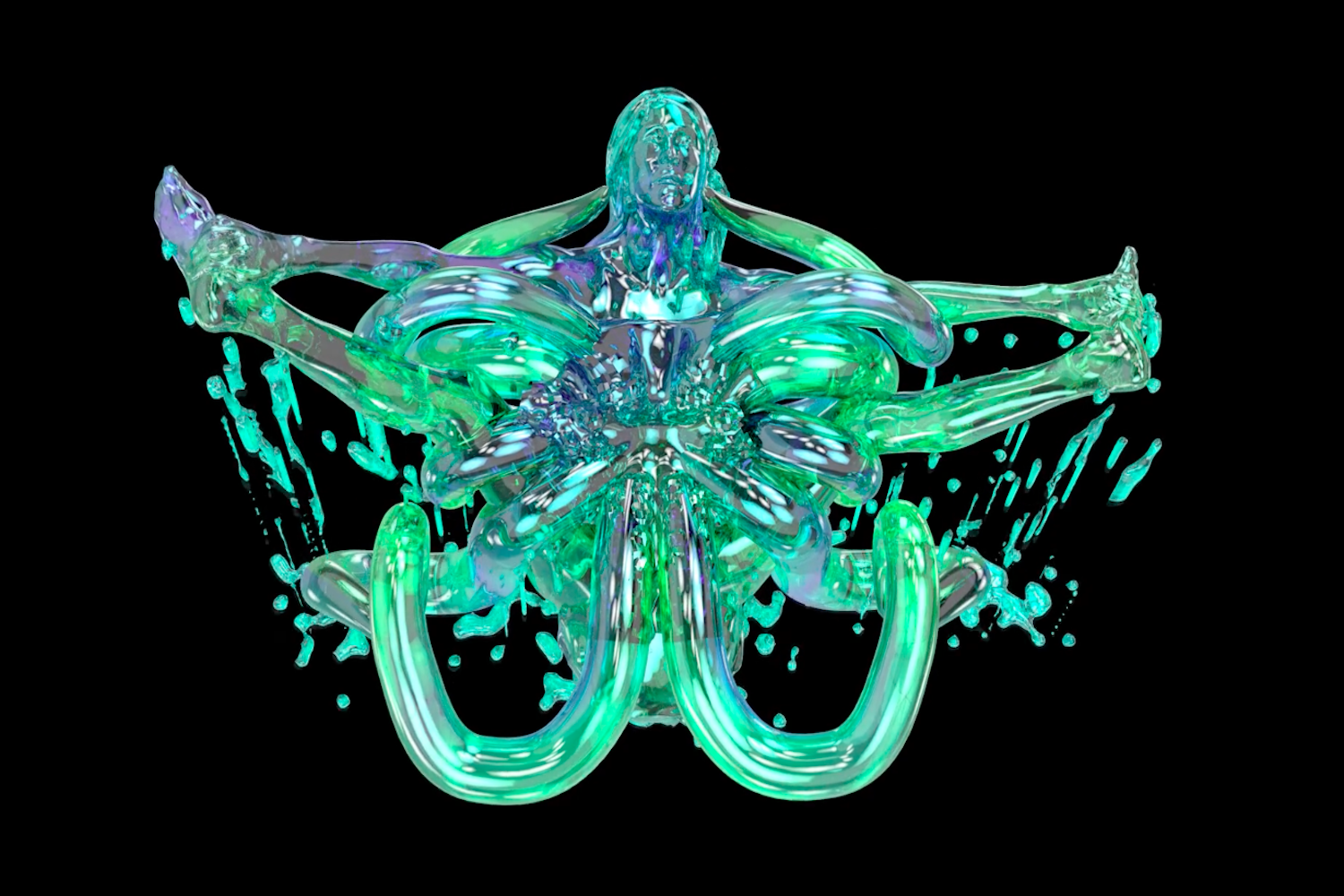

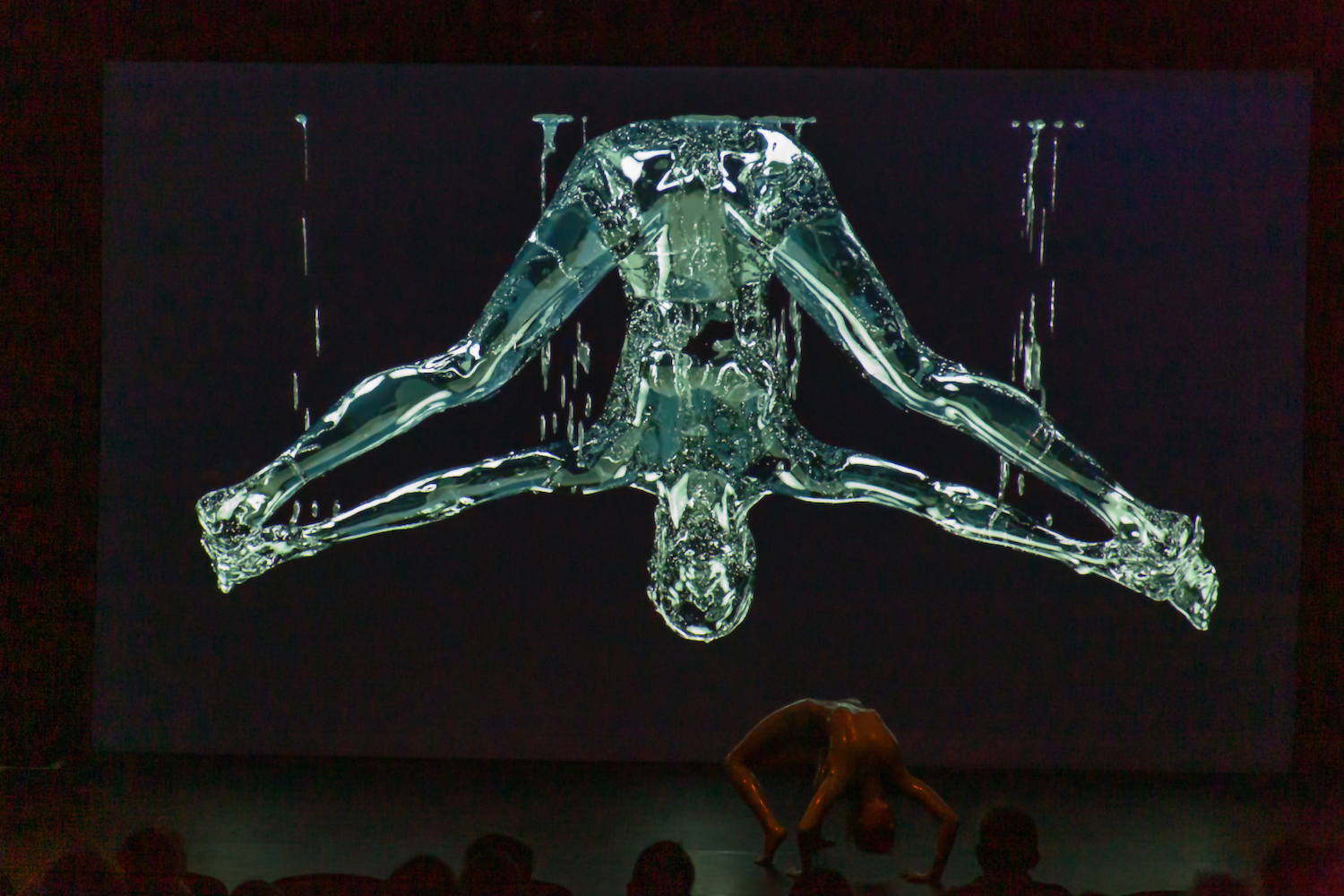

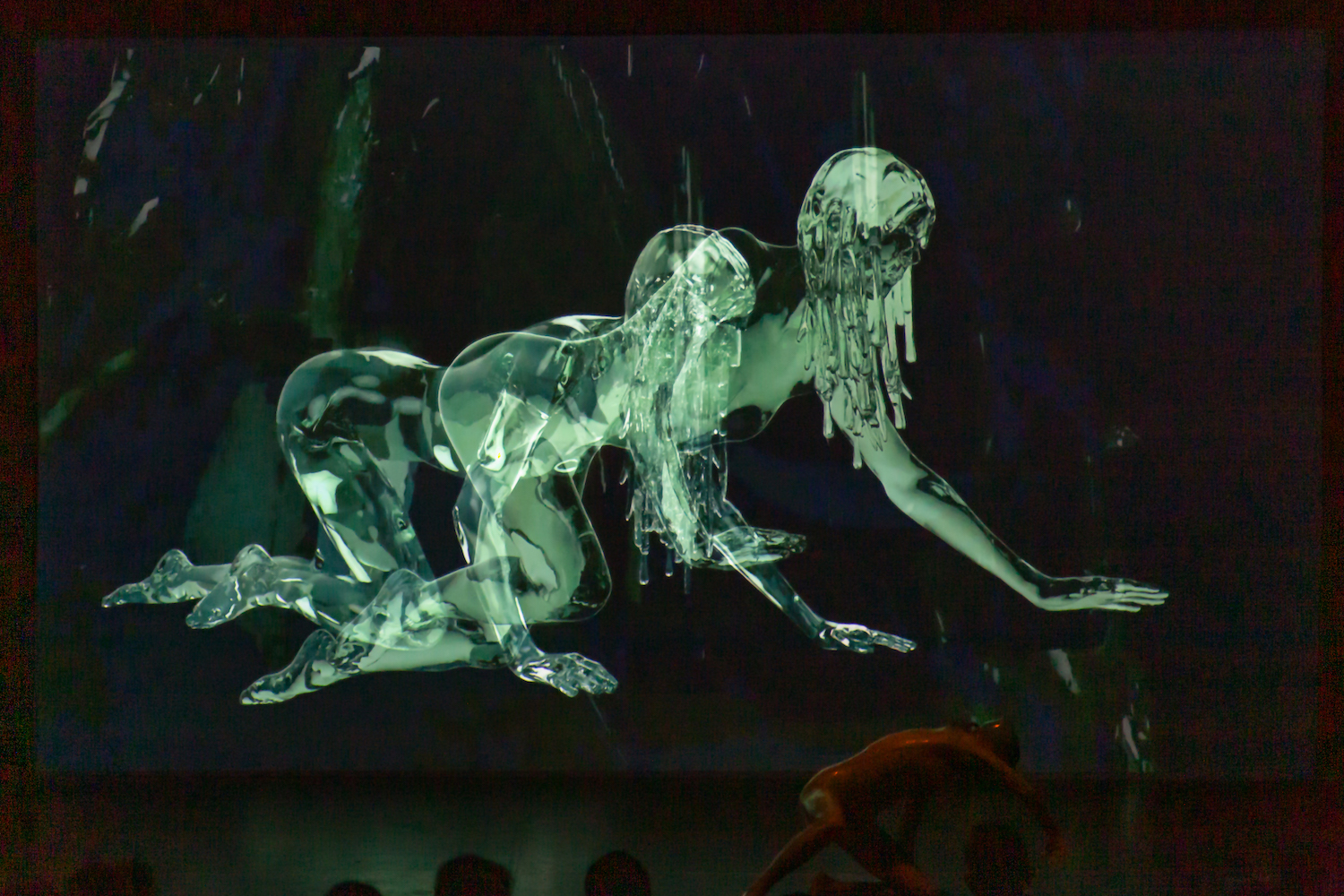

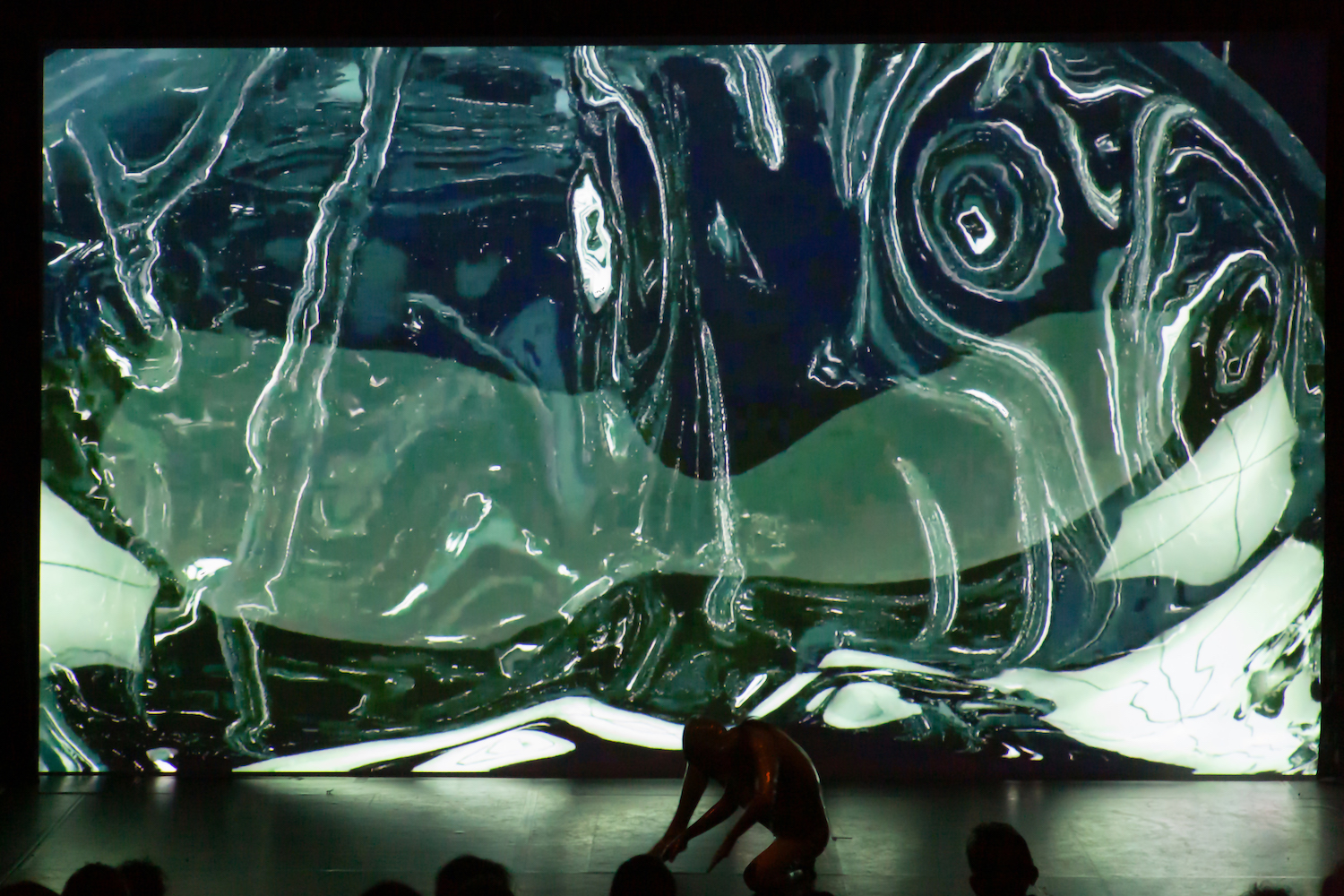

CB: Following the thread of water and movement flow, “Animations in Water” presents three works where I reflect on the sensorial interplay between the body’s interiority and exteriority, as well as the rhythmical relations of social community and nature, manifested through choreographic language. Lightning Dance (2018), is based on a long-term collaboration with the dancers from Bog Walk. The work belongs to the series developed around dancehall culture on the island of Jamaica. This piece investigates the influence of atmospheric electricity on behavior and the imagination. For these groups of performers, not only is dance a form of expression but it is also invested with curative powers. This piece is joined by two digital animations, Bestiaire (2019) and Favorite Positions (2018). Using hologram-like imagery, I visualize the fantastical transformations of a body in a state of perpetual change. Bestiaire takes inspiration from descriptions I found in Jorge Luis Borges’s Book of Imaginary Beings, after I scanned my body while morphing into a bestiary of fantastic creatures. The video sculpture Favorite Positions summons the octopus spirit to suggest a body without boundaries — a fully liquid being, born out of a state of constant rehearsal. The soul and rhythms that infuse this body move in multiples directions at once.

EM: Now your pony comes to mind.

CB: Flor, the little pony, that allowed us to become a centaur, or me a bird, I could fly when traveling on Flor’s back.