Maurizio Cattelan: Elad, I just ran into you in Milan, where you opened your first exhibition with Massimo De Carlo. How was that?

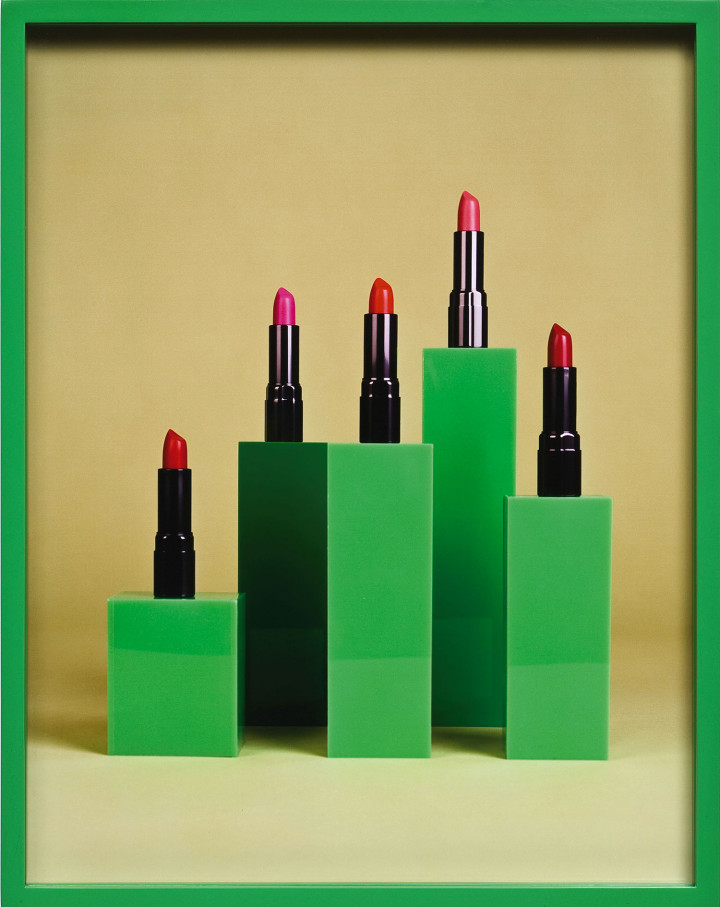

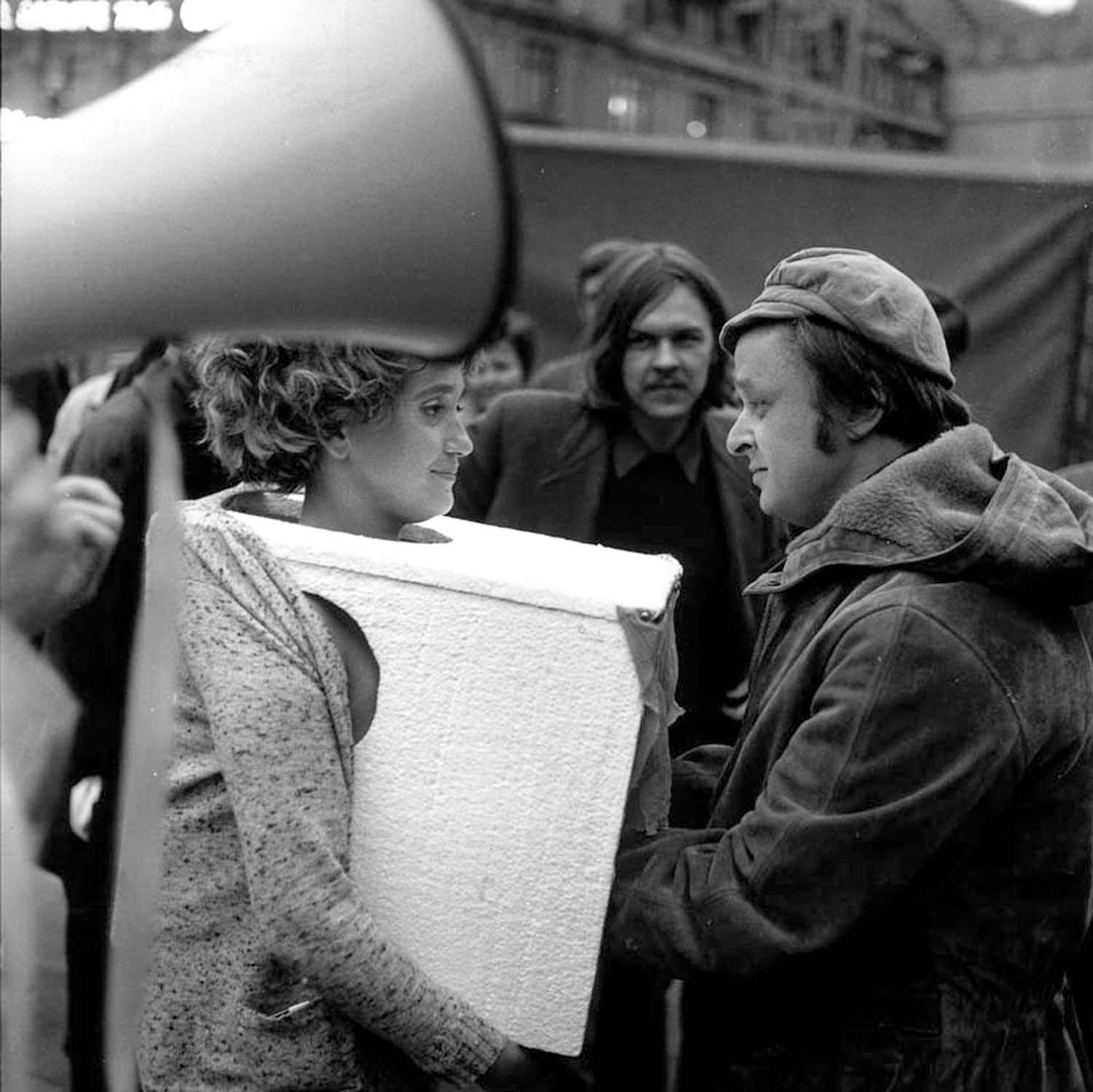

Elad Lassry: It was a very good experience to spend some time in Italy. I presented a new film and a series of images that I have been working on for the past year. The exhibition, as a whole, feels very involved with the extent of my practice. There is a mix between photographs that are the outcome of my research in the studio as well as images that result from found negatives and pictures that were already in circulation.

MC: Is it important for your films and photographs to be shown together?

EL: In the past, there were a few occasions when my films were exhibited apart from the photographs. The Whitney Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago presented projections that were slightly larger in a black box. Those were curatorial decisions made for those films, but there are qualities in this body of work that made it important to show the film at the same scale and in the same daylight conditions as the photographs.

MC: Can you tell me about this new film? How did it come together?

EL: The film is based on the late American choreographer Doris Humphrey’s Passacaglia (1938), which aired on National Educational Television in 1966. Like many of my previous films, the new work revisits the strategies that were used to document and mediate this historical dance performance. The camera angles I used are based on Humphrey’s diagrams and her theory of “invisible diagonals” that structure the theatrical stage.

MC: Do you think of your photographs and films as pretty?

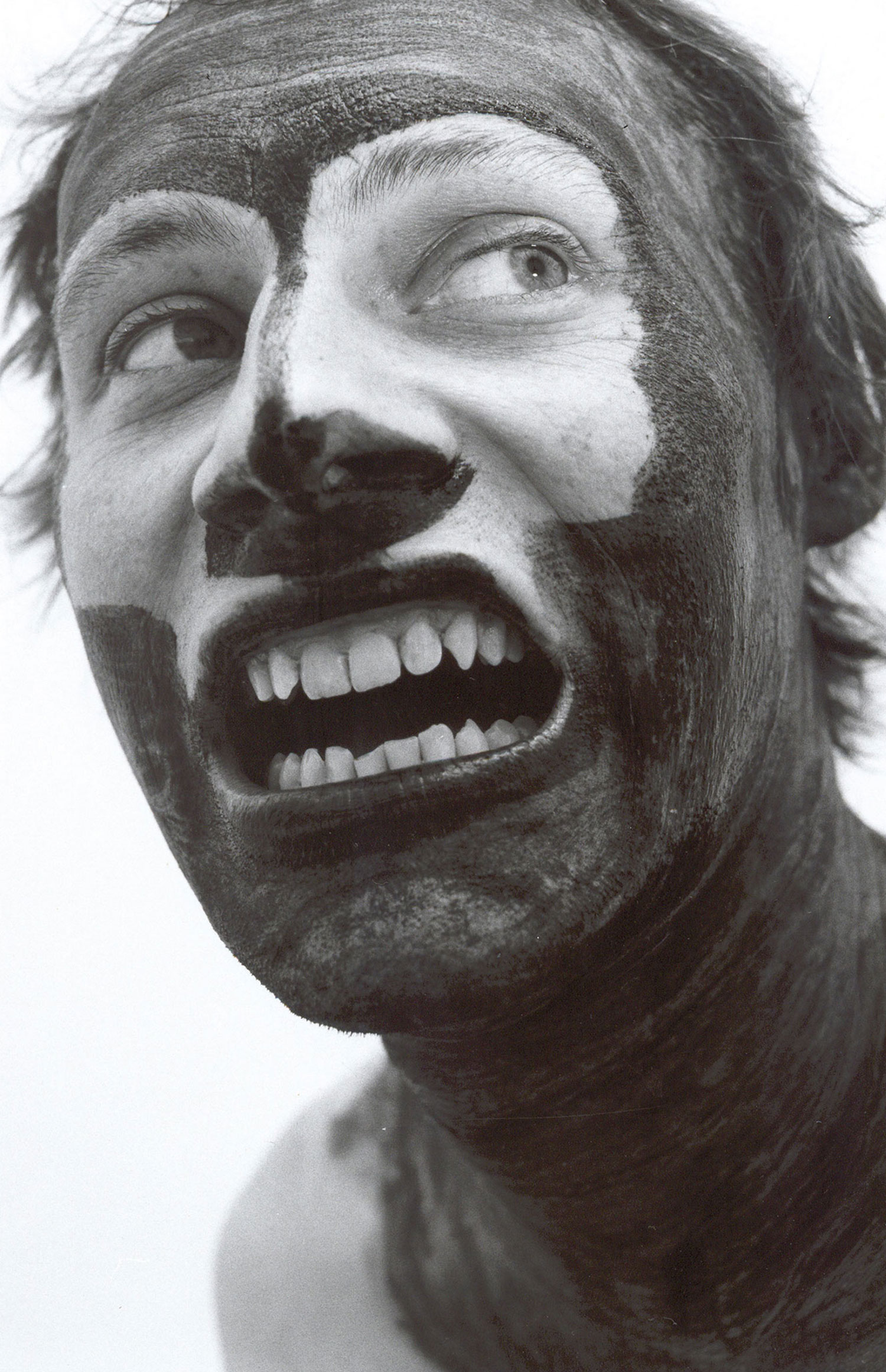

EL: I think many of my photographs end up being difficult to look at. In the context of my show at the Kunsthalle Zürich earlier this year, the press release referred to them as irritating, and I think that is an endearing quality that many of them have.

MC: But I also find your work to be very funny at times. Do you have a sense of humor about it?

EL: Many times the things that I find funny aren’t necessarily funny to other people. And the same is true the other way around. Even though I can understand why someone might find some aspects of the work humorous, I’m not really trying to be funny. Humor is already so pervasive everywhere else in the world, I just don’t know if there is much place for it in my work.

MC: I understand what you mean, Elad, but what do you tend to look at? Do you watch specific television shows or movies that influence your practice?

EL: This question has come up for me in the past, but I don’t watch television. While I haven’t owned a television in many years, I’ve managed to become aware of certain actresses and actors through other means. I usually know very little about a performer’s abilities when I approach someone to be in my films. I think of it as an engagement with the conditions of cinema, rather than anything that has to do with a given actress or actor’s previous experience in a specific film or television show. It’s just important that they serve the purpose of the image.

MC: I want to ask you a question about animals, but I’m not sure how to phrase it.

EL: Have you seen many of William Wegman’s early videos?

MC: No, not too many. I guess I want to know more about your animals. Do you own any?

EL: Yes, I have two standard black Poodles, Carter and Jessica; a Chihuahua named Tuna; and a Persian cat whose name is Judd.

MC: Do you think it is important to be an animal lover? I’ve tended to notice that artists sometimes reveal a greater sensitivity to animals.

EL: Yes, I can’t seem to understand a way of being in the world that doesn’t have an attachment to animals. I can’t grasp how animals cannot be relevant to someone’s life. I think animals are as fascinating as humans.

MC: Would you ever consider making a portrait of one of your animals?

EL: All of my composed photographs are based on images that already exist in the world. It would be hard for me to justify creating an image that bears the pretense of originality. If there was ever a need in my practice to recreate an image of two standard black Poodles, I would likely hire trained dogs. The readymade quality of animals that are trained to perform in front of a camera is most appealing to me. Besides, one of my Poodles is very badly behaved.

MC: Do your animals provide something for you that you don’t get from being an artist?

EL: The routine of caring for my pets offers a bit of refuge from the world.

MC: You seem to tire easily. Do you feel that the demands put on you are sometimes too much? I think this is something that concerns all of us individually. Are you tired now?

EL: I’m not tired in the sense that I need to sleep. But maybe we can take a break?

MC: Yes, of course. What shall we do?

× × ×

MC: Elad, why do you choose to live in Los Angeles? Why not live someplace more exotic or exciting?

EL: I have a very strict routine, and the relaxed environment of Los Angeles is the most productive context for me right now. This aspect of the city contrasts with my severe neurosis. It’s an easy place to strike a balance between isolation and sociality. Most of all, it’s just a good place to hide. I’m finding now though that it’s becoming harder to travel regularly because Los Angeles is so geographically removed from the rest of the world.

MC: But are you satisfied intellectually?

EL: Yes, I have a small circle of friends and people I am close with here. It is a very select group.

MC: Are they mostly artists as well?

EL: Yes, they are mostly artists and writers who I went to school with or who have been influential to me in some way or another. But I am also as comfortable with the random freaks I meet at the dog park.

MC: You’re thirty-three years old. Do you still feel young?

EL: My mother in Israel recently told me that I’ve been an old man since I was a child…

MC: Maybe then you’re already a mature artist? You do seem a bit older than I had expected…

EL: I’ve always preferred the company of older people. I remember feeling a bit elderly as a child. My mother also told me recently that when the other children would ask for candies, I would always ask for dried fruits.

MC: Before we met I had a different idea of how you might be.

EL: Are you disappointed now that you’ve met me?

MC: No, not at all. How about you? Are you ever disappointed with yourself?

EL: Not generally. Even though I’m confident about my recent bodies of work, I am however still plagued by doubt. I think this is natural, and I’m especially skeptical of younger artists who don’t experience this on some level.

MC: Can you describe what you’re feeling now that we’re nearing the end of this interview?

EL: I’m wondering why you invited me.

MC: I invited you because I find your work to be interesting.

EL: Can you talk a little more about this?

MC: I first came across your photographs in “Younger Than Jesus” at the New Museum, and I remember thinking that the images were all indeterminate and staged in a peculiar fashion. I knew then that we should talk so that I could find out what motivates you to create these images.

EL: It’s something to do with the rediscovery of pictures that were at one time exhausted. When I’m researching in the studio, I’m really trying to figure out how certain images can be redeployed or restaged in ways that address their original function in the world. These are images that have, in large part, run their course, and I want to find out if there is anything in them worth revisiting.

MC: I remember feeling a bit of loss when I first came across your pictures.

EL: Can you talk a little more about this?

MC: I’d rather we talk about something else.