We live in a time of complacency and apathy, when violence, climate disaster, and suffering are daily realities and yet action always seems to stall. Images depicting these things are overwhelmingly present in the world but still do not stir enough people to change. What is missing are the right images, and Doreen Lynette Garner’s exhibition “REVOLTED,” curated by Vivian Crockett for the New Museum, is full of them.

The exhibition presents the tearing apart of the corporeal collective, the result of the long history of white supremacy, colonialism, and violence toward people of color that lingers to this day. The space has been painted red and is illuminated by red fluorescent lights. Preferring the sharp poignance of only four pieces in a small room, the artist has emboldened their impact rather than fill a large space and risk losing the immediacy of the work and its meditation on the long-felt effects of racial brutality. As such, the room becomes a kill room as much as a museum exhibition, and the redness of it all points to that sense of seething rage.

Garner took inspiration from the 1773 revolt aboard the slave ship New Britannia, in which slaves managed to free themselves from bondage, gain access to the ship’s weapons, and wage a resistance that ended in the ship’s fiery end. The New Britannia was one of hundreds of ships to cross what is known as the Middle Passage, the transoceanic trek from Africa to the “new world.” The ships were hotbeds of unsanitary conditions where terrible afflictions ran rampant: diseases — such as syphilis, smallpox, measles, and many others — were transmitted from the slavers to the slaves or brought on by the “bloody flux,” an amoebic dysentery from contaminated food and water.

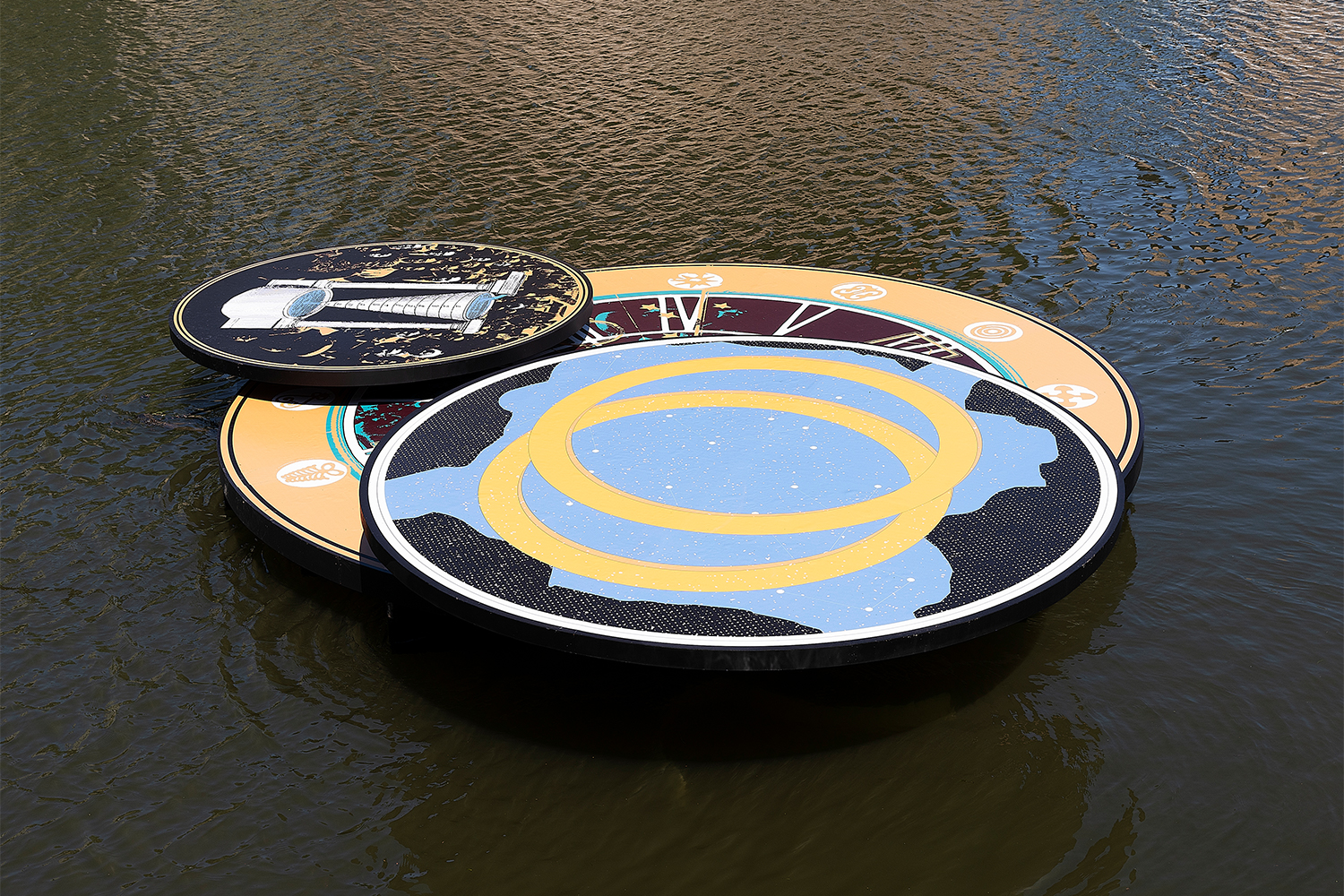

This is what Garner’s show opens up for us: the long bloody flux, which began with the brutalization of those already brutalized. Her works are sculptural and painterly, whether they hang on the wall, from the ceiling, or stand on a platform. They drip with both fierce action and sensitive placement. I’d Rather the Viscera of Me Floating on the Surface of the Sea Than Be Dragged Into Hell by Those Pale and Free (2022) hangs like a painting but can be seen as a topography of the damned. A disembodied field of peach skin dominates the top half of the piece, its surface pockmarked with blood, boils, rashes, and sores that can be seen as a landscape overrun with the disease of mankind (a visual response to “white purity”). A river of coagulated blood draws the eye from the center to the top-left corner while the bottom is heavy with a black field that recalls rotting flesh, blackened blood, and bile. And yet, there are parts that draw one in for closer inspection rather than recoil in disgust: the pinkish ooze filled with red chunks that may remind one of strawberry shortcake.

Take This and Remember Me (2022) clearly draws its composition from Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam on the vault of the Sistine Chapel. But where God and Adam lay, there is a black patchwork of shiny silicone covered with curly black hair like the scalp or pubis area of a human, splitting in areas to reveal a blood-red flesh, elsewhere sutured as if haphazardly sewn up. Across from this piece is the work Here hangs the skins of a surgical sadist!… (2022), which looks both sacred and demented. Taking the shape of a seated figure in a wired form, the work is draped with raffia (a twine made from the raffia palm native to Africa) and adorned with cowrie shells, known to be used by the Ojibwe peoples in North America. At the base of the work lies a silicone skin like recently sliced meat. At the top hangs a speed bag that doubles as a head, and, as the artist’s title suggests, is to be physically assaulted by those who identify as Black women, those who formerly identified as Black women, and those who were identified as Black women at birth.

This exhibition is as much about language as it is material and imagery. Revolted, in its double meaning, is the past tense of an uprising but also of one’s reaction of disgust to the grotesque. In this way the exhibition is also twofold: a telling of the artist’s response to the historic wrongs done to people of color; and a call to action now. Why haven’t we all revolted? Many people have called on more gruesome images to be disseminated widely in response to unjust incidents such as the recent shooting in Uvalde, Texas; and there is of course the precedent set by Mamie Till, who chose to reveal to the world the brutal result of her son Emmet’s murder. In Garner’s “REVOLTED,” the extremity of loss and the collective memory of racial and oppressive violence — the kind that does not die with the original sufferer, but carries along like a scar reopening and reopening, baring its viscera for all to see — is given to us to see what we’ve done and continue to do.