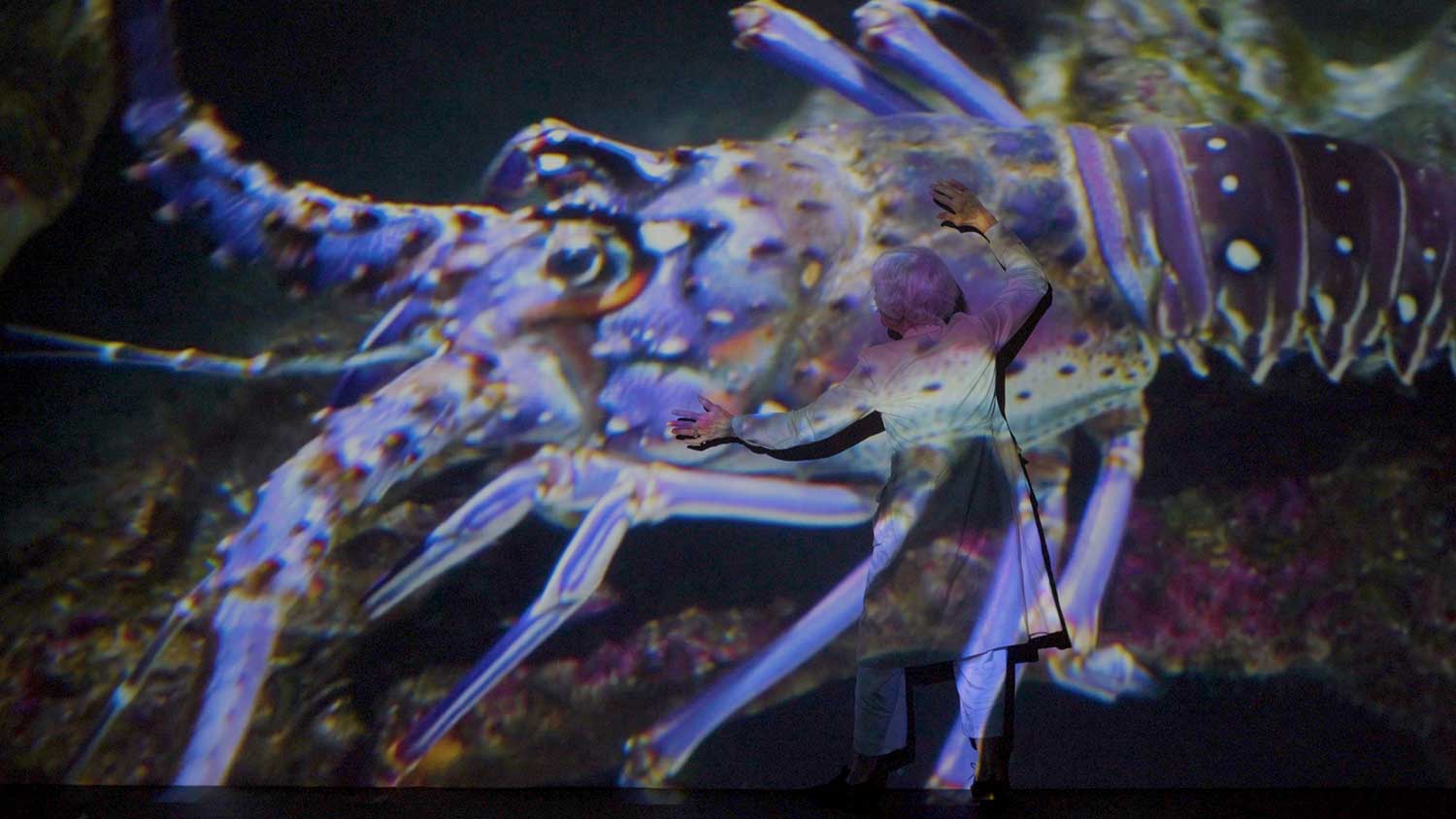

Questioning perception and experience, the Croatian-born, New York-based artist Dora Budor highlights the urgency of building new relationships between appearance and reality, introducing the ideas of an exhibition as a reactive organism and artworks as complex systems. On the occasion of her first solo show in an European institution, “I am Gong” at Kunsthalle Basel, the artist and the curator of her exhibition discuss the influence of history, cinema, science fiction, architecture and technology on Budor’s practice.

Elena Filipovic: It’s not unusual for you to mine the obscure histories of a place for your exhibitions. For your first institutional solo show in Europe, “I am Gong,” you started by investigating the nineteenth-century architectural origins of Kunsthalle Basel in relation to a nearby concert hall by the same architect. Can you say something about how history feeds into your work in the present?

Dora Budor: The problem with buildings and history is that they are both desperately static. That might sound like an oversimplification, because what I am thinking of precisely is not the way things exist in the present moment, but the form that they gain in which we get to know them — as they are represented, recorded, or preserved. In Bruno Latour and Albena Yaneva’s essay “Give Me a Gun and I will Make All Buildings Move” there is a perspective on making and viewing architecture that is equivalent to Jules-Étienne Marey’s photographic gun, which would completely abandon the static view of buildings and return to architecture as an animated, moving project. I wanted to make the building of Kunsthalle Basel function as a live system. The impossibility of acting on it or changing it led me to its “sibling” building — a neoclassical concert hall, called Musiksaal, located down the street, built only four years after Kunsthalle Basel as its auditory counterpart by the same architect, Johann Stehlin. The building has been under expansion and reconstruction for the last few years, which will be ongoing until 2020. So, at no point during the exhibition will the viewer see it — it remains a fiction, an idea of progress. This fiction, however, functions as a life motor of the exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, modulating its different elements. A real-time frequency transmission by the name of Tuning (Well, It’s a Vertebrate…)(2019) is established for the duration of the exhibition in which the concert hall, currently out of function, but in a state of reconstruction, gives impulses to the works and environments at the Kunsthalle. The process of the Musiksaal’s expansion and renovation involves functionally modernizing the building, while at the same time aesthetically bringing it closer to its original nineteenth-century state, and even archaeologically correcting certain historical intentions (such as the color of the whole façade, which was supposed to be the same as Kunsthalle Basel’s grayish limestone but was never realized, and bringing back the original colors of the walls, fabrics of the chairs, etc.). It is thus a time capsule blending its different historical features and correcting the details never achieved, all while rigging it beneath with the bones and breath of a new and necessarily modern infrastructure. It is a most vivid mash-up of times, progress, and modern demands, but it also speaks about a certain desire to preserve things — as in Luchino Visconti’s film Il Gattopardo (The Leopard, 1963): everything needs to change so everything can stay the same.

EF: The questioning of perception and reality is a kind of thread throughout your oeuvre, but it’s also about what might seem like a contradiction: the fact that you remain so doggedly attached to the real, i.e., not just making or getting fake frogs for an installation but tracking down and buying all eight thousand of the prop frogs that fell in an amphibian rain in Paul Thomas Anderson’s film Magnolia (1999) in order to use them in your installation Adaptation of an Instrument (2016).

DB: The world is full of objects, isn’t it? Some more, some less interesting, as Douglas Huebler notes. The objects I aspire to work with are the ones that have a specific history and memory attached to them, and are created for a very particular cause, whether that is to simulate a fiction or a real, visceral experience. I buy them, borrow them, and reroute them. Their value is not a deciding factor, but their uniqueness, life cycle, and purpose are. For this exhibition, a lot of pieces come from a distinct context, a precise time period, but also display the considerable amount of use and change they have withstood. In this exhibition they are all site- or history-specific; from the original 1973 Swiss-made Ubald Klug DS1025 modular seating elements, which were heavily used and handed down from one owner to the other, to the original parts of the nineteenth-century building of Musiksaal, which were cut out in the process of its re-making, or the architectural mock-ups of its yet-to-be-built facades and floors. I could never remake these objects (nor would I want to), as they are so tightly bound to the process of becoming a larger whole, with their predetermined role in the cycle of production. So, to answer your question, I often gravitate towards excavating something specific which speaks, even if not directly, of the larger conditions of its making. When it comes to fiction, I am not of an opinion that it entails creation of an imaginary world that would be opposed to the real world. It operates in dissensus and provides a view through the lens of cognitive estrangement — by changing the frames, the scales, or the rhythms; by constructing new relations between appearance and reality.

EF: You originally trained as an architect, and, a bit like your fellow architecture-drop-out-cum-artist Gordon Matta-Clark, you have managed to forge an artistic practice that exposes the psychic resonance of built structures. It’s no different with this project, which seems to put both the mutability of a built environment and the institution itself on exhibit. Indeed, instead of being filled with artworks in the conventional sense, “I am Gong” will effectively be both an ambiance and a kind of reactive machine in which you mobilize a live feed of sound frequencies from that nearby concert hall to create an evolving “score” for your exhibition.

DB: This process of connecting these two building was to create a “homeorhetic” flow between two sibling edifices: where the reach of equilibrium is not a homeostasis, but instead a continuous flow. In measuring the activities happening inside of the Musiksaal, the frequencies are transmitted to Kunsthalle Basel, affecting the environments in the exhibition. And by doing so, turning it into a sort of an instrument that will have a dual function: it will effect and modulate events in the exhibition, and over time build up and therefore measure a visible change in the system. In a way, one can think of Robert Morris’s 1961 artwork Box with the Sound of its Own Making, but on the scale of a building. The exhibition thus could be said to live on borrowed energy, transforming labor into the “life” or motor of the exhibition. When you mention ambiance, that is also something I thought about a lot, specifically the idea of creating an “affective atmosphere” as a certain feeling in a room. German phenomenologist Gernot Böhme describes it as a relationship of environmental qualities and human condition — with an accent on subjectivity and sensory evocations of memory. It is a very German thing… Franz West used the term Befindlichkeit to describe it, perhaps as “a state of experience of being.” One of the ways it can be transmitted is through soundscapes, or the sonic atmosphere of a place. I was interested in an atmosphere that would be unruly, impermanent, invasive. This led to the making of a modulating soundscape in collaboration with composer Celia Hollander called The Sound-Sweep (2019), whose source you cannot see since not a single speaker is visible, but only hear (and feel). The soundscape inhabits (or possesses) the cavities behind or beneath the institution’s walls, floors, and ceiling, most of which have remained unused after the building’s renovation in 2004. The sound in the exhibition is always experienced differently, as it evolves and changes with impulses fed to it from the construction site across the street. The title comes from a J. G. Ballard science-fiction short story about noise pollution and the new industry called “Sonovac” that has developed for its elimination. In the story, low levels of sound are left in solid surfaces and slowly trickle out of them over time, giving the inhabitants of the spaces emotional flashbacks, causing a disease.

EF: Cinema ash, several iconic 1973 Terrazza couches, dust chambers with the colors of a J.M.W. Turner painting, a biomimetic bird, Beethoven’s 9th Symphony: Why are these wildly different things in your exhibition? What do they have to do with each other?

DB: I conceive of artworks as complex systems in which I try to collide and to situate their parts into interdependency. There are no temporal boundaries, as the pieces perform on a nonlinear timescale in which also the historical events are revived into the present. In the exhibition there are, as you mention, different things and events from different eras; however the connections between them do exist. In The Preserving Machine (2018–19), a biomimetic bird endlessly performs its flight navigated by the first composition ever to be performed at the Musiksaal, Beethoven’s 9th. In The Year Without a Summer (Klug’s Field) (2019), the title holds a reference to 1816, the so-called Year Without a Summer, when the eruption of Mt. Tambora in Indonesia, and the ash and debris that lifted into the atmosphere, blocked the sun and caused anomalous environmental conditions in the whole northern hemisphere for three years in a row, also bringing significant social and cultural changes. At that time the picturing of landscape and material objects starts refocusing on the atmosphere itself. Both the conditions of progress — the Second Industrial Revolution — and exacerbated atmospheric conditions will make known a completely new type of air: dusty, foggy, and palpable atmosphere, as described in Ruskin’s verbose “The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century” and portrayed so vividly by Turner. He is the first one to bring the thermodynamic introduction of fiery matter into culture. But not only does he paint it, he literally leaves his studio skylight unrepaired with a gaping hole, letting the weather soak into his paintings. In the exhibition his atmospheres are simulated as unstable images, using environmental test chambers that are employed in factories and production to test the effects of time and decay on a wide range of products, from heavy-duty vehicles to outdoor light fixtures or signs, computers, military equipment…

EF: Let’s talk technology. I’m struck by the following: you are among a generation of artists for whom quite sophisticated tech is a central tool, despite technology still being so often thought of in the art world as a predominantly masculine domain.

DB: I had a very interesting conversation with an artist recently who makes technologically involved work, and while he spoke of the precise rules that he assigns to the installation of his artwork, I spoke of behaviors which only guide and modulate but do not necessarily determine the outcome. This inherent difference comes from a different position: in which letting go of control, for me, allows a place for variation, unexpected, as well as affect to enter the equation. In this show, I relinquish control to the forces that are beyond my control. In Zeros and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture, Sadie Plant traces (and rewrites) a whole history of female and trans people’s involvement in technology — from the very beginnings of software, which were woven into the patterns of textiles, or Ada Lovelace’s implanting of her own footnotes into Luigi Menabrea’s study on the Difference Engine, to Grace Hopper’s first programming and invention of computer bugs — the ways that women have always worked, encoded, embedded, and slipped into and through other’s production. I think, because we have a deep understanding of noise, that we can see all the variations of a message.

EF: This brings me to the fact that you are born in the very year that Orwell described his dystopian novel 1984, in which the world is portrayed as falling victim to perpetual war and omnipresent surveillance. Now that’s just a quirky coincidence, but I can’t help think of it in relation to so many of the projects you’ve worked on, and in particular this one, in which the audience is confronted with the aftermath of what looks like some disaster that is itself controlled by invisible forces that are powered by a kind of surveillance system you’ve set up to listen to not a person, but a building…

DB: Our built environment has become over time the producer of both natures and nature concepts — as cybernetic devices that manage a teeming ecosystem, continuously sensing and adapting. They are their own recording and preserving machines, constantly surveilling. Here I can’t help but think of Jack Burnham’s statement: “Artists are ‘deviation amplifying’ systems, or individuals who are compelled to reveal psychic truths at the expense of existing societal homeostasis. With increasing aggressiveness, one of the artist’s functions is to specify how technology uses us.” Whenever I work with technology, it is never the end goal — it is used to speak about the broader condition and reflect back on human experience.