Pop Art was brilliant in its ability to mirror society — to reflect not only the shiny, colorful plasticity of its surface, but also reveal the fissures beneath it. Two Whitney exhibitions explore the dark underbelly of this movement. Drawn from the permanent collection, “Sinister Pop” frames unsettling irony as the era’s key sensibility. Along with objects by Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol, works like Judith Bernstein’s excoriating political collages, Jim Nutt’s grotesque drawings, and snapshot photography by William Eggleston depict the range of Pop’s influence. An accompanying video and film exhibition, “Dark and Deadpan: Pop in TV and the Movies,” investigates the symbiotic relationship between mass media and Pop Art. This succinct but smart show of TV ads, video art and underground film illustrates the rampant cannibalization of popular culture to subversive and sinister ends.

A selection of mass-media footage traces the razor-thin, often shifting line between dark and deadpan. Campaign ads for Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon display a sophisticated understanding of montage techniques and the ’60s youth cult, deploying their appeal to promote dubious political agendas. The godfather of deadpan, Andy Warhol, hovers between complicity and critique. His commercial for the restaurant Schrafft’s — an ice-cream sundae casually filmed with psychedelic video effects and a soundtrack of banal chatter — is adjacent to a film clip from 1981 by Jørgen Leth and Ole John in which the artist eats a Burger King hamburger. By today’s standards, this pokerfaced gesture of fast-food consumption appears almost grotesque.

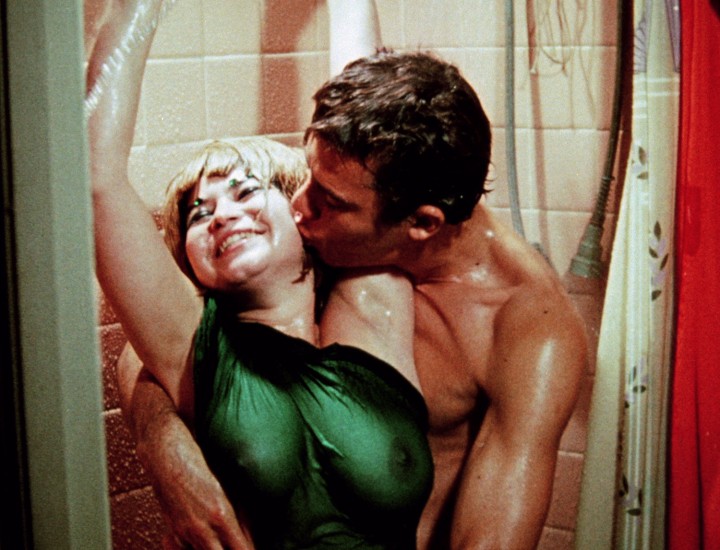

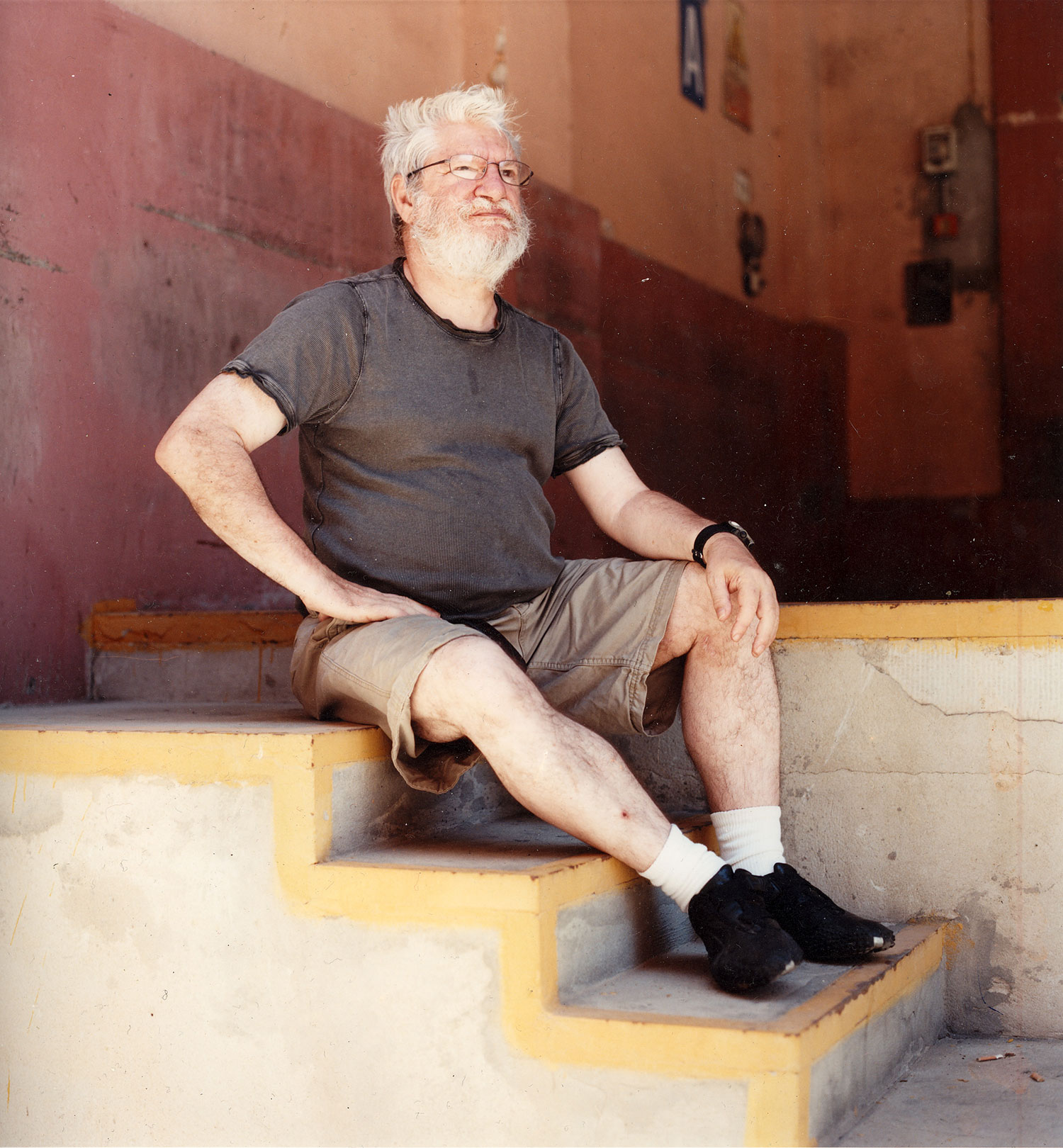

However, the most evocative thread of “Dark and Deadpan” illustrates artists’ negotiation of sexual liberation at the moment of its co-optation by capitalism. Herbert Marcuse named this channeling of desire into a need for instant consumerist gratification “repressive desublimation.” Kenneth Anger parodies tropes of popular romanticism in Scorpio Rising (1963), a soft-focus homoerotic homage to biker gangs set to ’60s girl-group hits. Animator Fred Mogubgub’s jumpy collage film, The Pop Show (1967), shuffles images of consumer and sexual desire against a pulsing soundtrack of Rolling Stones and The Beatles. The quick-cut film features a young Gloria Steinem as a soft-drink spokeswoman “drinking” Pepsi and cleaning solution with the same blank grin on her face. Ger Van Elk’s conceptual film of shaving a cactus provides a punny counterweight to Sherman Price’s trailer for The Imp-Probable Mr. Weegee (1966) — a dizzying parade of giggling, topless ingénues. But George Kuchar’s HOLD ME WHILE I’M NAKED (1966) truly shines with humor and pathos. This story-within-a-story features the loveless director’s attempt to make a glamorous erotic film. Knitting together passionate filmed scenes with vignettes from his lonely life, Kuchar exposes hippie hedonistic sensuality as a constructed yet alluring fantasy. This imbricated critique continues to define Pop’s avant-garde legacy.