Danh Vo’s much-anticipated first institutional solo exhibition in Japan finally opened at the National Museum of Art after the Japanese government ended the country’s state of emergency on May 25. The exhibition’s title, “Danh Vo oV hnaD,” suggests the key role that mirror images play in both the show’s installation and accompanying publication.

Featuring approximately forty pieces, the museum survey was deeply impacted by the global phenomena of COVID-19, not only because the opening was delayed by two months. Some artworks couldn’t be delivered, and Peter Bonde, one of the artist’s closest collaborators, was not able to travel to Japan to work on site due to border restrictions. Vo, however, was already in Japan to install the exhibition, and was obliged to stay there much longer than planned.

Vo often notes that his works are the result of a series of chance occurrences. The sudden, unanticipated opportunity to remain in Osaka allowed him to explore Japanese culture further. It lead him to a new collaboration with a lacquer craftsperson, in which the traditional technique of kintsugi was applied to a carton of Lucky Strikes originally sold at a PX shop. Kintsugi (golden joinery) is a method of restoring broken utensils by binding pieces with lacquer mixed with decorative gold.

Some installation works were also altered due to circumstances. For example, Untitled (2020) was intended to revisit the work Vo presented at the 2019 Venice Biennale, in which Peter Bonde created a series of paintings on mirror foil. Because this was not possible in Japan, Vo himself painted one panel — a strategy that Vo and the curatorial team surely discussed as a means of articulating the installation without jeopardizing its value. This challenge added further conceptual layers to the work.

The space is mainly divided into six rooms of various size. In a second room visitors encounter the massive installation titled Untitled (2019), in which a series of huge mirror-foil paintings by Bonde dominate the installation under bright white light. In between these playfully reflective surfaces are photographs of Vo’s nephew Gustav, taken by Heinz Peter Knes, and a work on paper by the artist’s father, Phung Vo. Also a large lantern by Isamu Noguchi, Akari PL2 (c.1973), is on view here — an object that again appears in the final room.

Much of the rest of the exhibition features work with a strong connection to the Vietnam War. Central Rotunda/Winter Garden (2011) consists of a chandelier placed in a transport pallet, originally from the banquet room in the former Hotel Majestic in Paris, where the Paris Peace Accords were signed. In the next room, bunches of horsehair and wooden objects are situated on the floor alongside a letter by Jacqueline Kennedy. The pieces on the floor are from two completely dismantled chairs that once resided in the White House Cabinet Room during the Kennedy Administration. President Kennedy and Robert McNamara, the US Secretary of Defense, sat on these chairs when discussing war strategy. Even though viewers may not know precisely what it is they are looking at, the aura around these objects is potent. Perhaps it is the weight of history. As Vo points out, “we are the consequence of decisions made by powerful people.”1

Chief curator Yuka Uematsu said there was no particular intention to select works that directly connect to a Japanese cultural or sociopolitical context. However, some works do resonate in terms of US-Japan relations. For example, the Lucky Strike carton with kintsugi restoration mentioned earlier might be read as an attempt to mend the twisted relationship between the US and Japan since 1853, when Commodore Perry sailed into Tokyo Bay to command the Japanese to lift their isolation policy; or 1945, when General MacArthur landed in Tokyo to set up the Allied occupation headquarters after World War II. Also Robert McNamara, whose items repeatedly appear in Vo’s exhibitions, played an important role in the US bombing of Japan in 1945. Or perhaps it is a divided US that is to be mended via this subtle method — a subtext in keeping with Vo’s gentle sense of humor.

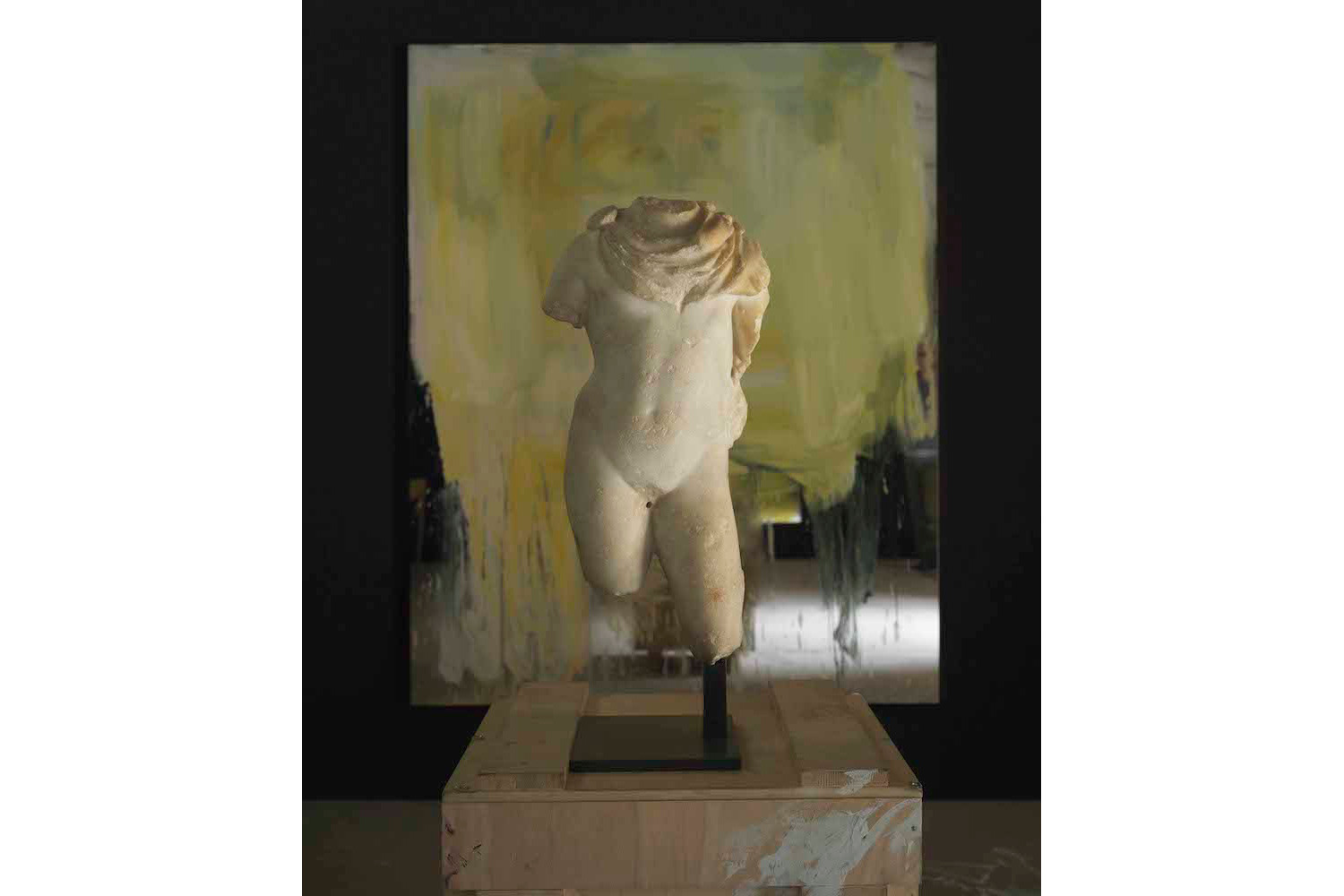

In the final room, Vo revisits his ongoing conversation with the legacy of celebrated sculptor Isamu Noguchi. Here, Akari PL2, made of washi paper and bamboo, stands between a marble torso from the Roman period and We the People (2011–16). The latter is one of more than 250 individual copper pieces that together form a 1:1 replica of the Statue of Liberty. These objects are situated amid walnut root balls from the farm of Craig McNamara, son of Robert McNamara and the founder of the Center for Land-Based Learning, which is dedicated to helping high school students develop social and human capital in their communities.

Vo’s manner of selecting objects and deploying them in space is truly mesmerizing. In some ways it echoes the ceremonial Japanese Way of Tea, in which the host arranges the space and carefully selects utensils and artifacts for guests on specific occasions. Guests in turn guess the connotation of items through minimal conversation, participating in an act of openness, anticipation, and appreciation. In this exhibition, Vo proves to be a masterful host.