Having received nearly simultaneous invitations from a pair of Parisian institutions, Cyprien Gaillard proposed an exhibition that could heap the two together and, as if in the claws of an excavator, capture the city, currently heaving with social unrest. The Berlin- based artist pulls his exhibition title, “HUMPTY \ DUMPTY,” from the eighteenth-century English nursery rhyme, popularized by Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1871). In Carroll’s novel, Alice buys an egg that grows “more and more human,” and seemingly comes alive as Humpty Dumpty. Alice’s sense of wonder, faced with the terrifying and surreal, carries through here.

Conceived in two chapters, “HUMPTY” comes first at Palais de Tokyo, opening with Gaillard’s readymade Love Locks (2022): industrial- grade plastic sacks overflowing with rusted remnants of padlocks that have been cut to prevent bridges, like the iconic Pont des Arts, from sinking under the weight of this twisted expression of love. Nearby is Giorgio de Chirico’s drawing of Oreste et Pylade (1928), Greek mythology’s boy cousins whose childhood friendship grew into proverbial loyalty. With entrails made of motifs from classical architecture, the two literally take on the form of the built city, a fate echoed in Gaillard’s video Lake Arches (2007), shown just opposite. Here, in the artist’s very first video work, we see two of his friends dive into deceptively shallow water surrounding Ricardo Bofill’s post- modern housing complex in a Parisian suburb. A bloody broken nose yields a scar for life.

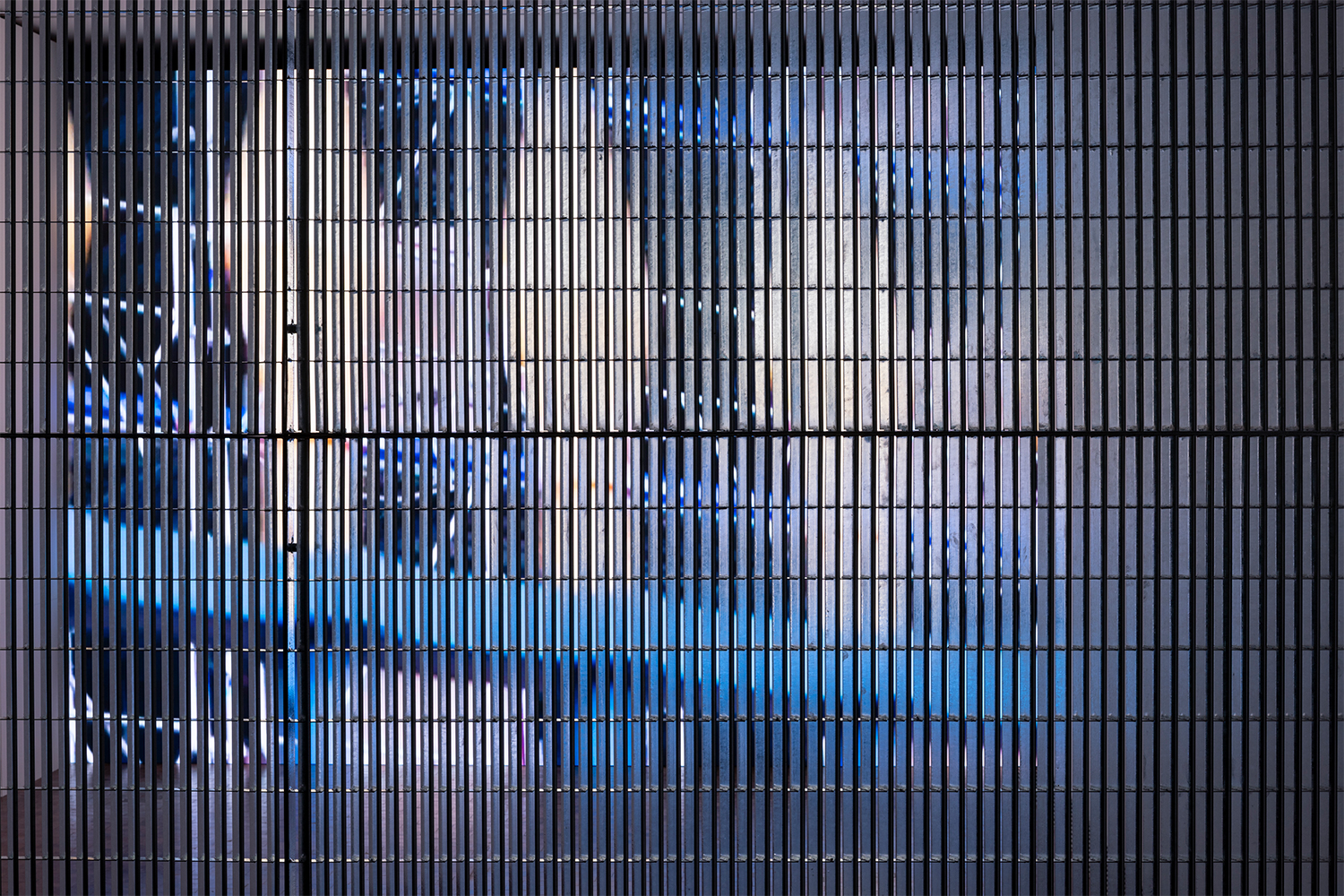

Of course, the story of artistic lineage that Gaillard is trying to create would not be complete without Robert Smithson, but the series of the American artist’s drawings from the early 1960s resonates less with Gaillard’s work here than Daniel Turner’s Eiffel Cable Burnish, Provenance: The Eiffel Tower (2022). For this work, Turner paints the gallery walls with blue and green dust he collects from an elevator inside the Eiffel Tower. His ephemeral installation provides a backdrop for Gaillard’s extraordinary readymades: Gargouilles crachant du plomb, 1873 1914 (Gargoyles vomiting lead, 1873 1914, 2022). Under German bombing, lead scaffolding, erected for repairs to Eugène Viollet-le-Duc’s renovation of Reims’s medieval cathedral, melted and ran through the structure’s drainage system, cooling as it poured through gargoyles’ open mouths. Suspended on delicate wires, the grotesque figures become artifact: of architecture, war, and society’s often futile attempts at reconstruction.

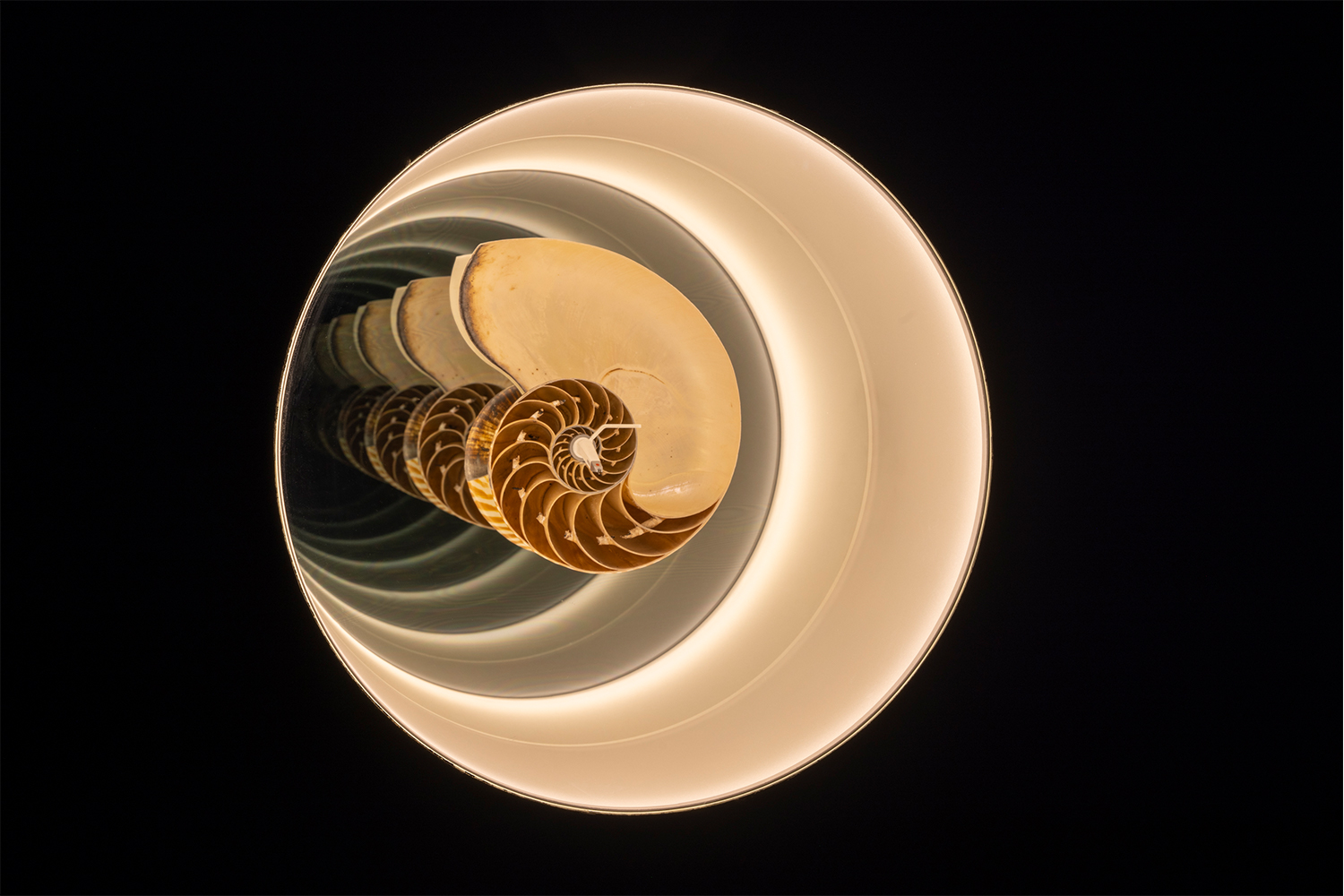

There’s a story that a crate of rose-ringed parrot chicks, cracked on a tarmac at Orly airport in the late ’70s, was what launched the invasive flocks currently thriving in cities across Europe, a case of Humpty Dumpty all over again. For Formation (2021), an ultra-panoramic color video of a flock of the once-exotic birds moving across a German cityscape, Gaillard called on animal documentarians to help him capture the breathtaking images. Huddled before the artist’s fifty- meter-long screen, curving with the museum’s expansive concave wall, is one of the few rare examples of Käthe Kollwitz’s (1867– 1945) work in sculpture: her Mother with Two Children from 1933, a bronze that Gaillard borrowed from the Museum of Berlin. Kollwitz’s crouching mother wraps strong arms around two young children (the artist had two sons, one lost as a young man in the First World War). Her bare back, rounded like a carapace, becomes their shelter.

Rem Koolhaas’s renovated Lafayette Anticipations, once a warehouse for the family-run retail empire that gives this institution its name and its funding, hosts “DUMPTY,” chapter two. Here, suspended midair, is Jacques Monestier’s Le Défenseur du Temps (1979), which Gaillard has rescued from Paris’s Horloge District. Restored by monumental watchmaking specialists Prêtre et fils in Besancon, Monestier’s animated sculpture, broken and nearly forgotten under layers of pigeon droppings for almost two decades, has come alive once again. Gaillard has set the clock to run backwards, as if we could go back and capture that lost time.

A soundtrack from Laaraji and an ethereal remix of pop music from two decades ago, the moment Monestier’s clock stopped ticking, amplifies a piercing nostalgia that reigns here. After the show, when Monestier’s sculpture is reinstalled in its original location, just steps from the Pompidou — just as Kollwitz’s sculpture will be repatriated to Berlin — Gaillard’s photo of his late friend Gaël Foucher will accompany it. The color image will face Le Défenseur. As boys, Gaillard and Foucher had loved watching the automate count time with its movements.

To end, I quote an essay by novelist Olivier Schefer — which will be published in the exhibition catalogue — who concludes his text in turn with a quote from Vladimir Nabokov: “The future is just the old man turned upside down.”