Cosima von Bonin’s exhibition “Songs for Gay Dogs” at MUDAM, Luxembourg, is defined by dynamics of generosity and restraint: what of herself she chooses to make accessible and what she holds back. In a time when access to artists (and not just their work) is almost expected, von Bonin seems to say, “I’ve given you so much. Don’t push it.” In Do Nothing Club (2021), hundreds of books from the artist’s personal collection are stacked atop a wheeled plinth. A Dictionary of Marxist Thought (1983) sits alongside The New Poodle (1986); Rupert Everett’s autobiography rubs shoulders with Female Serial Killers: How and Why Women Become Monsters (2007). The work is less monumental than others exhibited but feels particularly pertinent to von Bonin’s practice. If a person’s book collection is an indication of who they are — their taste, politics, hobbies, and pleasures (guilty or otherwise) — we can assume that it’s the artist’s intention to pledge this cross-section of her psyche to us viewers. This candidness nevertheless comes with a caveat in the form of Fence (Corner Version) (2021). The plushy black barrier fencing off her books acts as a physical boundary between viewer and artist – a reminder of our position as bystanders, not participants.

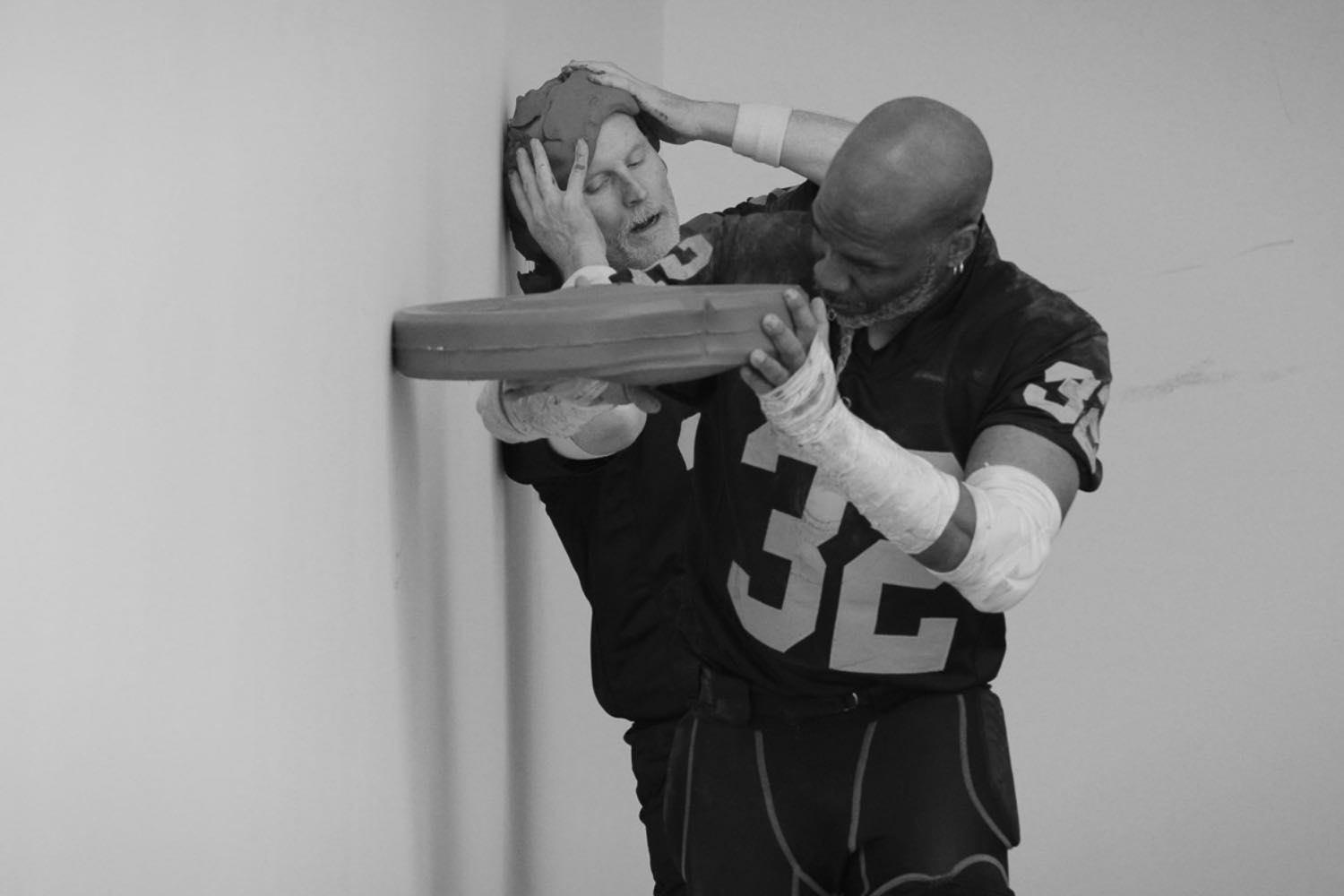

Throughout the exhibition — not quite a retrospective but featuring greatest hits from the past seven years — von Bonin brandishes the pop-culture iconography that has come to define her practice. Daffy Duck, Bambi, and Bart Simpson are her entourage. These cartoon icons were designed to be emotionally expressive, and their global ubiquity gives viewers an immediate point of access. Von Bonin uses these characters (and many more) as blank canvases for feeling: it’s easier to relate to pain and strife when it’s projected onto a Looney Tunes character instead of an actual person. In Open Your Shirt Please (2019), Daffy Duck — famous for his on-screen neurosis and egotism — battles encroaching negative space that threatens to consume him across five velvet-covered panels. He eventually loses the fight to the shadows, resulting in a single all-black rectangle. As Clara Drechsler writes in her essay “Demon Clearing Service” for the exhibition’s catalogue, “There’s no one who would rather be Daffy than Cosima. Sadly, the requisite qualities are not sufficiently pronounced in her. But perhaps they do share the same demons.”

On the floor of MUDAM’s cavernous foyer, three tiny stuffed piglets face off across a green square of woolen fabric, in a direct reference to Mike Kelley’s Arena series (1990) in which the late Californian artist would arrange stuffed animals around the perimeter of blankets, placing them with a precision that neutralized any cuteness or comfort in the toys. Von Bonin’s work, Mike Kelley is my Goddess (2023), positions Kelley — in no uncertain terms — as an influence and guiding force. Where Kelley’s stuffed animals were decaying and neglected, Von Bonin’s are pristine. Her works, meticulously crafted from high-quality fabrics, pursue a seemingly unattainable perfection — a dynamic that typifies the unequal expectations for women artists compared to their male counterparts. These tropes are reinforced by the titles of other exhibited works: Open Your Shirt Please (2019), Killer whale with long eyelashes (2018), and Mae Day Petite Version (2024) all allude to pressures placed on women artists to perform, to dress-up, to submit. In the freestanding panel works Gaslighting and Love Bombing (both 2023), Bambi has lost his spots. A silhouette of the fawn sits below text that informs the respective titles of each work. It’s unclear whether Bambi — and the artist by extension — is the victim or victimizer of the titular psychological abuse; in either case, innocence (or perceived innocence) is corroded.

In a sense, “Songs for Gay Dogs” is a sitcom, and von Bonin is the protagonist: a depressed but effortlessly stylish heavy smoker who rarely gets out of bed, uses retail therapy to escape the horrors of real life, and would rather talk to her French Bulldog or any of her cartoon associates over real people. Whether these traits are factual or fictitious is unimportant; we love her because we can relate. The artist’s own disposition seems inseparable from her work. Her reluctance to explain, to give us more, is widely known — but what more could a viewer want?