Described as “the trend to end all trends,” #corecore was a paradoxical TikTok hashtag that briefly garnered mainstream attention at the beginning of the year. Just what did its chaotic, nonsensical, and melancholic output tell us about our relationship with contemporary online culture?

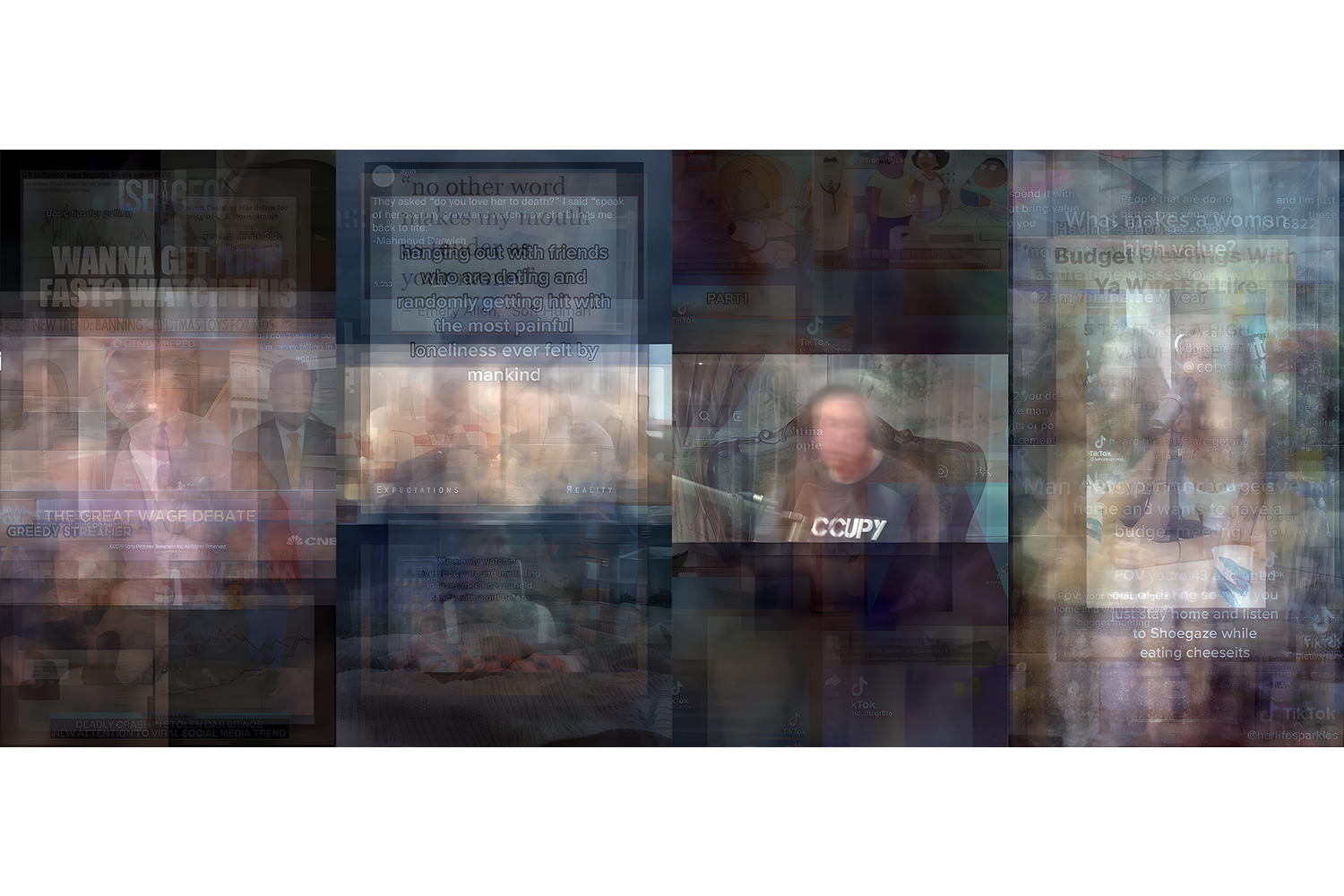

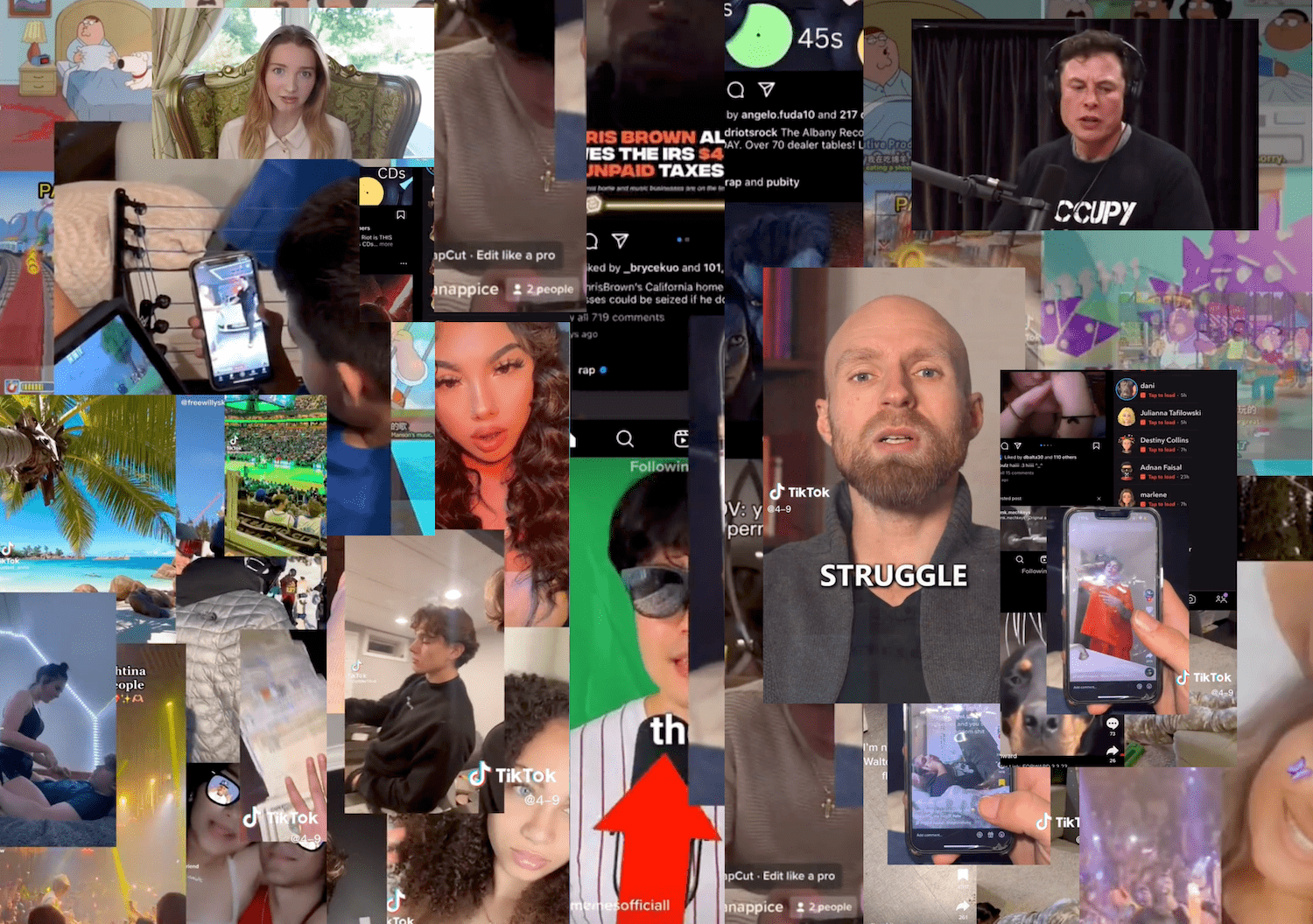

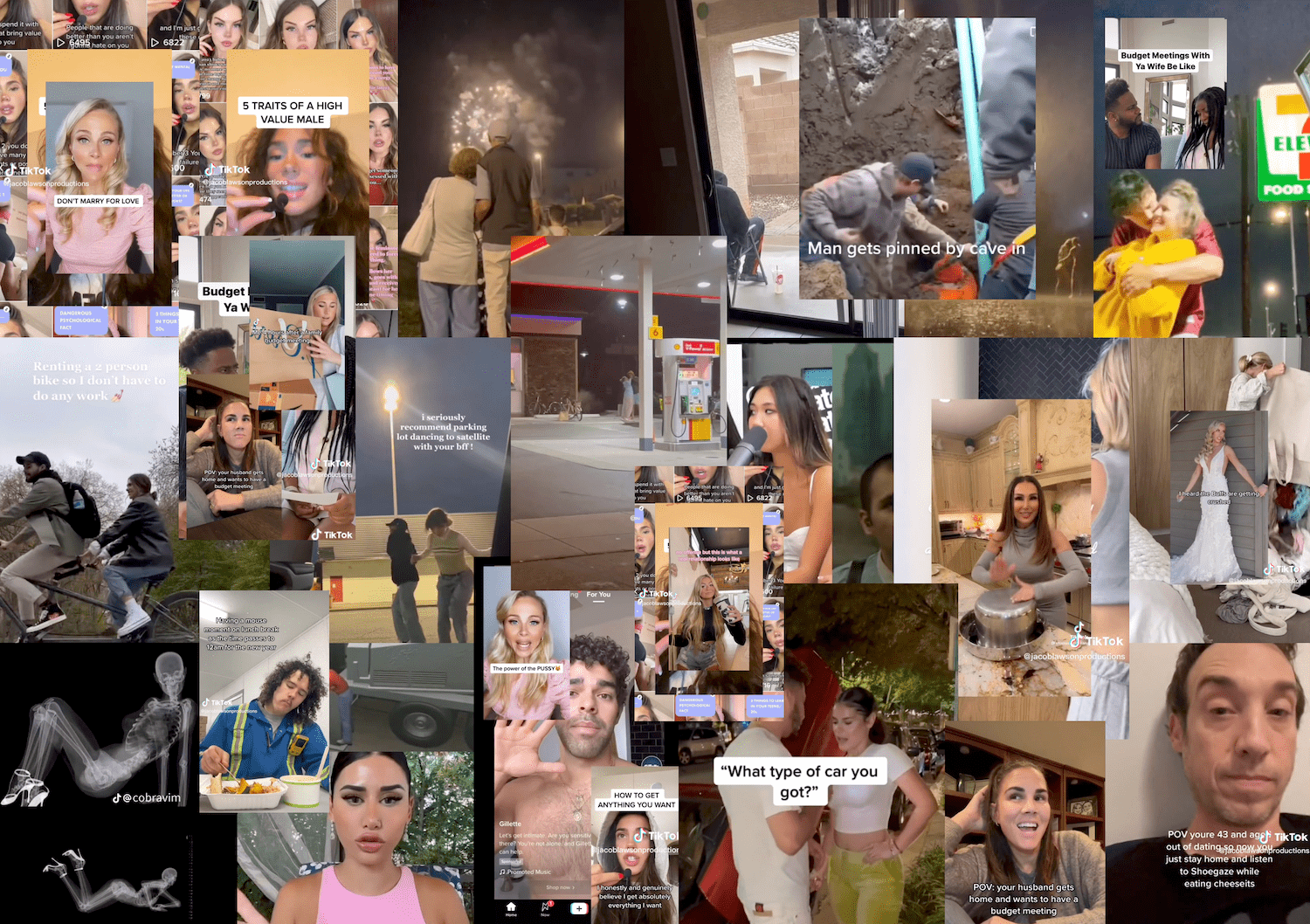

You are lying in bed. Your phone is about twenty-five centimeters away from your eyes. Content glides across the screen. The actual contents of this content aren’t of any particular importance in this instance. All you seek is stimulus with the appropriate tonal qualities to wash over you, to envelop you in a fine-tuned, abstracted vibe. Having abandoned a YouTube wormhole, your fingers automatically steer your attention to TikTok, where — after an indeterminate amount of time — you’re presented with a video depicting alpha- female GRWM influencers outlining the attributes and virtues of high-value males, a man taking a dinner break alone at work while the clock strikes twelve on NYE, a cornucopia of #relatable #marriedlife budget meeting videos, a street interviewer asking a seemingly wealthy young woman how many cars she has, and a team of construction workers attempting to save their colleague from a collapsed structure, all in under twelve seconds.1 And yet, despite the stark contrasts in subject matter, it is all coagulated into a consistent vibe, no doubt helped by the ambient Aphex Twin soundtrack. It’s hitting just the right tonal frequencies. It’s perfect. You look at the hashtags. You’ve found #corecore.

***

#corecore was first used on TikTok in July 2022,2 although uses of the word predate this by decades (more of which later). However, it wasn’t until later that year that writer Kieran Press-Reynolds began to notice its ascent. Writing for No Bells in November, he stated that “#corecore has no mission statement, no how-to video, not even a basic description of style,”3 and that the earlier interpretations of the hashtag were “frenetic — they were these rapid-fire fifteen- second montages of surreal memes with intense music and didn’t have much of a discernible meaning beyond the pleasurable rush of recognizable audiovisual material.”4

In terms of etymology, there is a logic to TikTok users’ initial interpretation of #corecore. Taking the definition of the core suffix offered by journalist Chance Townsend, that it describes “shared ideas of culture, genres, or aesthetics and groups them all into one set category,”5 you can undertake the equation that #corecore is a category defined by the very act of categorization. In other words, it is a trend whose defining characteristic is the trending of trends. So, while there is no immediate implication of an aesthetic here (unlike, say, weirdcore), there is an implication of a methodology of consistent inconsistence (or inconsistent consistence).

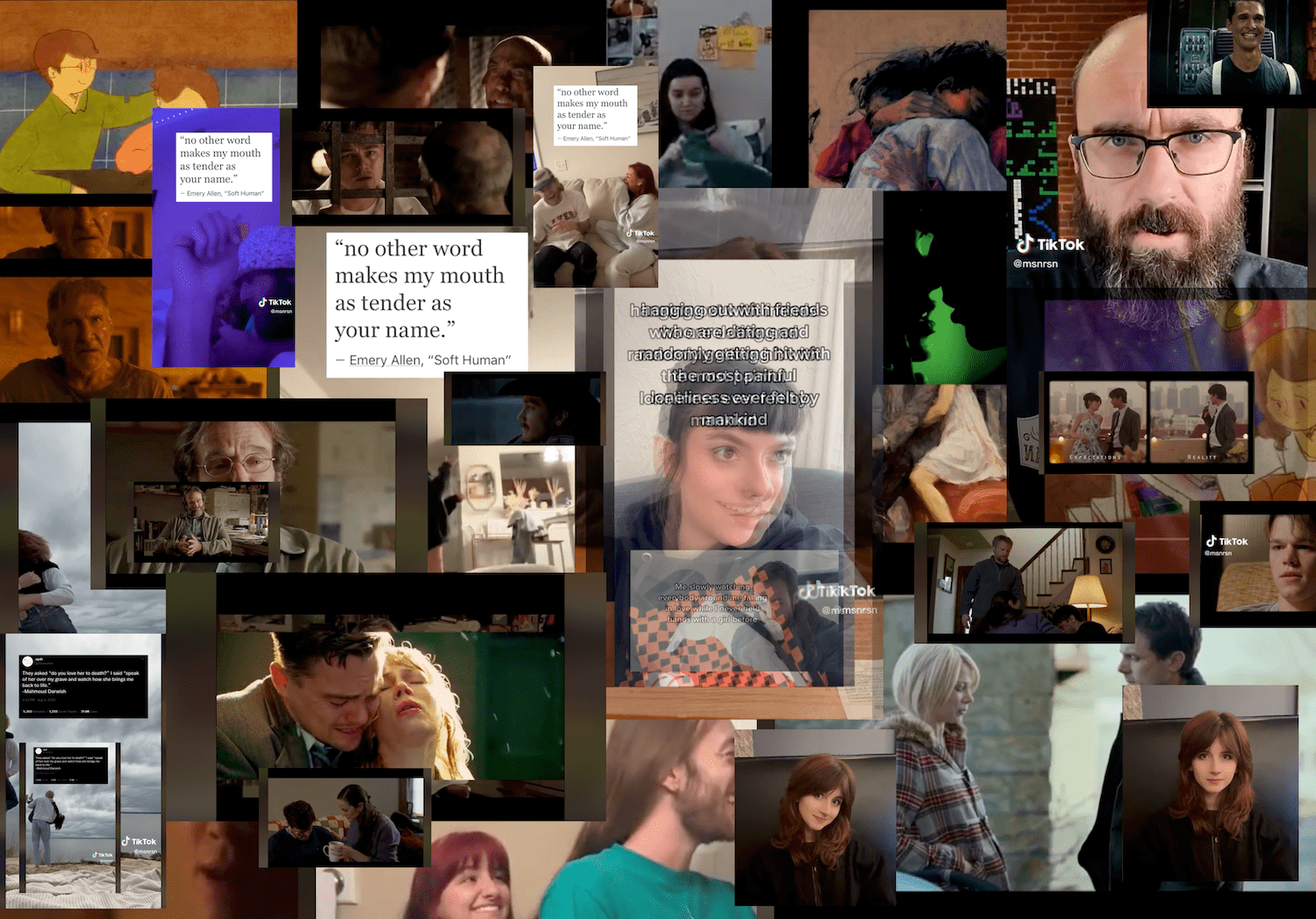

This outset of a chaotic and disordered structure deftly captured feelings of a more generalized, technologically induced disarray that appeared to resonate with the young people6 who form the bulk of TikTok’s usership. However, during its ascent, the anti- genre increasingly expressed a melancholia that was initially just an undertone.7 This particular strain of ennui was communicated through the layered application of media portraying senses of yearning or (at times) trite, aphoristic sentiments that usually launched critiques locating the root cause of this collective melancholia in consumerism, capitalism, technological atomization, systemic injustices against human groups, and irreversible climate change. In other words: expressions of endcore.8

There was a subtle generational nuance to this wielding of aphoristic-melancholia-as-critique; and that is the aporia of a post- ironic sensibility often found in the terminally online, in which an omnipresent glaze of potential ironic intent is cast over all forms of sincerity, so one is left with three conflicting notions: The first is that what you are receiving is a genuine — albeit oversimplified — critique of, say, capitalism. The second is that what you are receiving is subtly mocking this same oversimplification, or at least brandishing its kitsch naivety to signal a cultural fluency. The final notion is that it is simultaneously sincere and ironic, that it celebrates its oversimplified critique (with the celebration itself forming part of the critique). This final option articulates a notion that the targets of critique themselves are so overt, so entrenched, that sometimes all you can really say about them is that we truly do live in a society.

Of course, this technologically mediated expression of melancholia was not groundbreaking, and #corecore could easily be seen as a reprise of aspects of vaporwave,9 which was also borne out of a sense of detachment that is the native dialect of a now long-naturalized postmodernism.

***

As previously remarked, there was an aspect of #corecore — imposed by its own etymology — that took trends and trending as its subject. The sentiments articulated on this premise were ones of a sense of decision fatigue brought about by the (still active) proceleration of micro-trends and cores. #corecore’s maximalist collaging of media invoked a sense of — to borrow a phrase from sound artist George Rayner-Law — “stimuli shorn of meaning,”10 and established an exaggerated, satirical critique of not only the proceleration of trends, but also the formal qualities algorithmically encouraged by TikTok, as well as the wider rhythms and tones of a semioblitz11 that corrupts daily experience of urban life in the West.

The runaway acceleration in the proliferation of micro-trends increasingly clutters the present with aesthetic paradigms of the past. There are more of them, happening more often, and their life cycle is increasingly short. As a result, an increasing ideological and aesthetic pressure is applied to the present, and there’s only so much it can take. In her appearance on the “It Girl Theory” podcast last year, trend forecaster Mandy Lee discussed this proceleration and its possible consequences within the context of fashion:

The trend cycle will continue accelerating to the point where we […] will not be able to identify what is on trend. There’s no information, no one’s informing their decision about what they should buy […] all this influence around me means nothing, everything is conflicting, everything is back at the same time, I don’t know [where] to look for inspiration, so I’m going to just wear what I want. […] You can kind of see [the collapse of the trend cycle] right now too. […] It’s a lot of things overlapping at once and I think there’s more tastemakers than not-tastemakers in a way.12

From these observations we could posit the onset of an anti-incubatory terminus of cultural phase space resembling The Game. For those uninitiated: the simple rule of The Game13 is — and will always be — that if you think of The Game then you’ve lost The Game, whether you like it or not. And once a micro-trend has been named and defined then it loses its potency, whether you like it or not. #corecore was an approach to cultural creation that signaled an awareness of this fallacy as its premise.

***

We are bombarded by media, by content, and now, after prolonged exposure, we’ve built up a tolerance. For younger generations, it’s all they’ve ever known. But whereas overstimulation would once have been remedied by a period of seclusion or downtime, it is now the case for some that an absence of content is equally as distressing. This leads to a situation in which it is an act of self-soothing to expose oneself to a more fine-tuned barrage. In the same way that white noise is created by emitting “all frequencies across the spectrum of audible sound in equal measure”14 yet paradoxically also serves to soothe and aid sleep, #corecore emerged from an unexitable topology of stimulus in which in order to switch off, we can tune in and turn on, but there is no dropping out: not anymore. The world we inhabit is increasingly constructed of images, of media,15 and a shimmering lacquer of things-as-content recasts the semiotic foundations and historical authenticities of the IRL through URL filters. We forget where media ends and where we begin.16 Our boundaries become porous, we mix up outsides and insides.

This is precisely the experiential mode outlined by Franco “Bifo” Berardi in 2009, one in which the “acceleration of information exchange” produces “a strange kind of existential state, in which exhaustion bleeds into insomniac overstimulation.” It was also the hive mindset of #corecore.

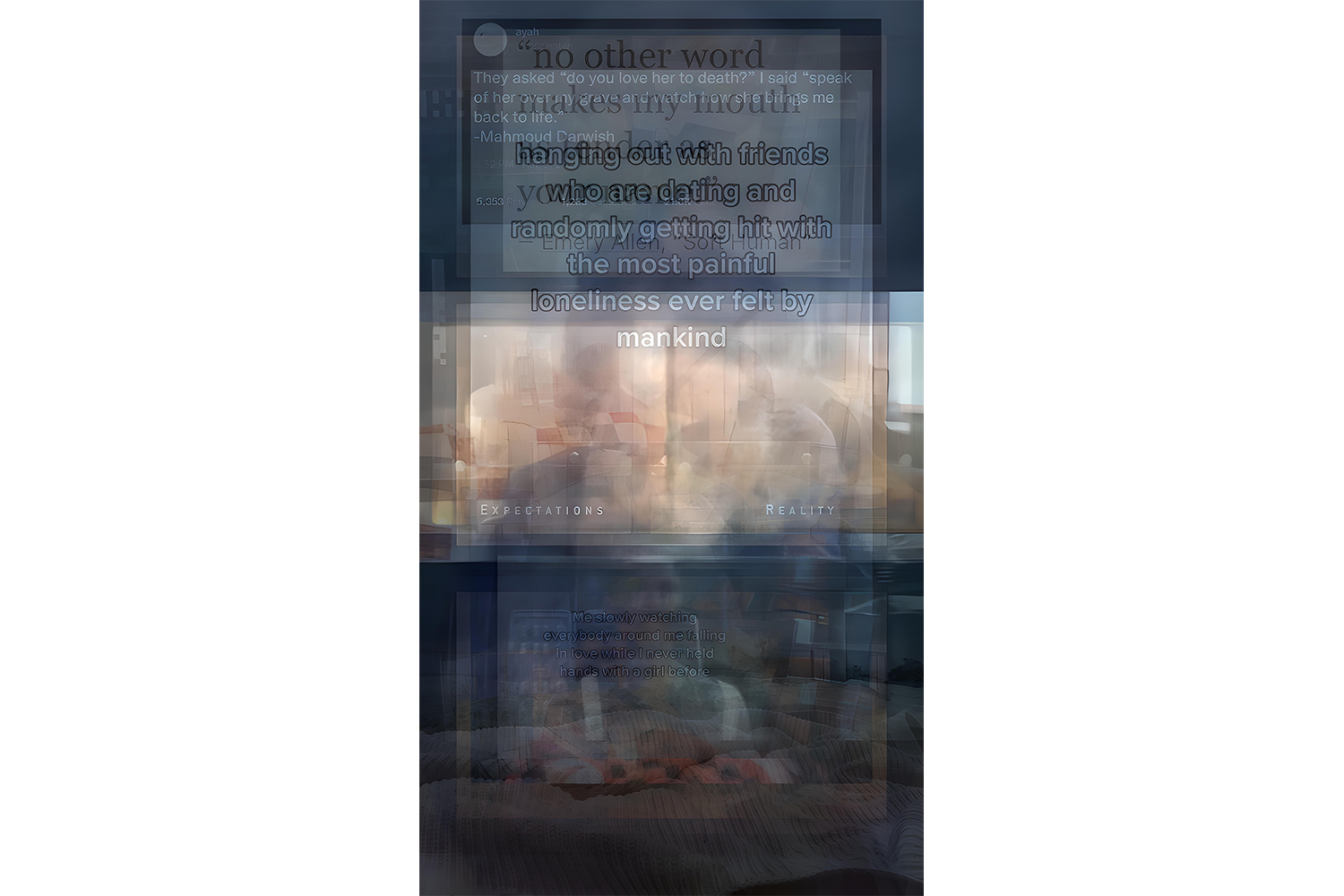

Users of the hashtag conducted an excessive superimposing of material that would, we suggest, be better thought of as emergent processes of hyperimposition. If, in superimposition, the composing units still retain their existence as discreet and recognizable, then hyperimposition can be conceived of as a process in which the mass and saturation of composing units disintegrate the existing semiotic or formal distinctions altogether, leading to a semioblitzed aesthetic Shumon Basar termed chaoscore.18

Further — more literal — examples of hyperimpositional processes can be found in Kevin L. Ferguson’s ongoing project of visualizing entire films in one image through sequential summing,19 as well as Brett Bergmann and Benjamin Roberts’s We Used to Be Friends,20 which is a simultaneous, overlaid playback of every episode from the first season of the sitcom Friends.

#corecore too established this ethos of “the medium is the mass”; of the sheer weight and rate of memetic and aesthetic nodes appearing and dispersing in a hyperimpositional composite. While #corecore videos did not always overlay all-media-at-once in quite such a literal sense as the examples above, they still — not least through their brevity and saturation of references — invoked a sense of semantic satiation (the phenomena whereby words lose meaning through rapid repetition); of semioblitz, of “references and tastes all unmoored from their provenance.”21

Hyperimposition is a transformative process in which you can, by accelerating the BPM of a drum loop through the 100s into the 1000s, pass through gabba and enter nirvana.22

***

Let us return, one last time, to the etymology of the trend. As stated by Kieran Press-Reynolds, historically, core suffixes have “been used online as ready-made descriptors pointing to clear-cut aesthetics.”23 But cores aren’t neutral bracketing tools; cores change the things they are categorizing: cores are intensifiers.

To illustrate this, let’s compare cores with another suffix of categorization: isms. Compared to cores, isms feel softer, more nebulous, more open. Cores are pointed, concentrated. This is most likely because cores are haunted by their original prefix: hardcore. cores make a thing more thingier. They saturate, they concentrate. For instance, #surrealcore would be like surrealism, but more so. With this semiotic turn in tow, #corecore’s paradoxical feedback loop set itself up as an ouroboros of intensification, a positive feedback circuit. In a partial counter to Press-Reynolds’s initial observation that there is no instruction manual for #corecore, we would contest that there does in fact appear to be an innate methodology constructed by the term itself. In 2007 the elusive and prolific Australian musician Buttress O’Kneel released a mixtape titled “core-core” that uncannily resembles the aesthetic trappings of the more recent incarnations.24 The very implication of #corecore’s paradoxical outset seems to impose a maximalist nonsensibility.

This nonsensibility, this “medium-as-the-mass” is, at its core, actually a preoccupation with scale as an abstracting force. One of the repeated thematic and stylistic turns in #corecore was, put simply, to step back and see the bigger picture. To attempt to comprehend the processes that were (and still are) unfolding and making the present so extreme, intense, and dense. A technique mirrored in multiple #corecore videos is the iconic use of scale deployed in Godfrey Reggio’s Qatsi Trilogy,25 released between 1982 and 2002. These films consist primarily of slow motion and time-lapse footage of cities and natural landscapes, and contain neither dialogue nor vocalized narrations: their tone is entirely set by the juxtaposition of images and music.

***

As well as the more overt critiques of capitalism, consumerism, and inequality, which by their very nature must increase their scope of analysis to a systemic level, #corecore’s chaotic and anachronistic layering of clashing styles also dealt with scale on another — albeit less initially obvious — register.

To understand this, we need to use a term that the writer Timothy Morton coined in 2008 after they were struck by a “strange, existential feeling that there were phenomena too vast and weird for humans to wrap their heads around”;26 and that word is hyperobject. Climate change, COVID-19, and financial collapses are all examples of hyperobjects. We can see examples of their consequences, but we can’t grasp the thing-in-itself.

We posit that #corecore attempted to examine or illustrate systemic processes at the delirious level of the hyperobject of communicative media; hyperimposing cultural and memetic units into an ever- increasing pile of info-slop witnessed from the dizzying scale of nonlinear global networks.

It is through this that we can conceive of scale as a force of abstraction. A force that the theorist Kodwo Eshun articulated in relation to Sadie Plant’s seminal work Zeros and Ones (1997).27 Speaking in 2000, he commented that:

Sadie rejects all metaphors, nothing is like [something else]. Everything is scale, can be on the one hand microscopic, and totally macro as well. Everything can be molecular and molar […] You start thinking how across scale and materials, general processes emerge […] At a certain point you want to be maximalist.28

#corecore was a program of scale undertaken from an anti- anthropomorphic POV, an insensate delirium scanning an ultimately inconceivable hyperobject of communicative media; and yet it was also a program of yearning and melancholy; of cancelled futures, of attempts to reconcile with endcore’s cauterized horizons.