Chiffon Thomas’s sculptures are a vexed dance between laws of prohibition and compulsion for transgression. For his solo show at Perrotin, Thomas debuted fourteen untitled works responding to the social architecture of Catholicism – a system that underwrites rigid inscriptions of bodily conduct into its seductive aestheticism of gleaming decoration. Concerned with the appearance of the body and its construction within a system of belief that delegates both harm and repair, the exhibition negotiates fleshly scenarios that neither fantasize flight for ecstatic liberation nor accept defeat by looming catastrophe.

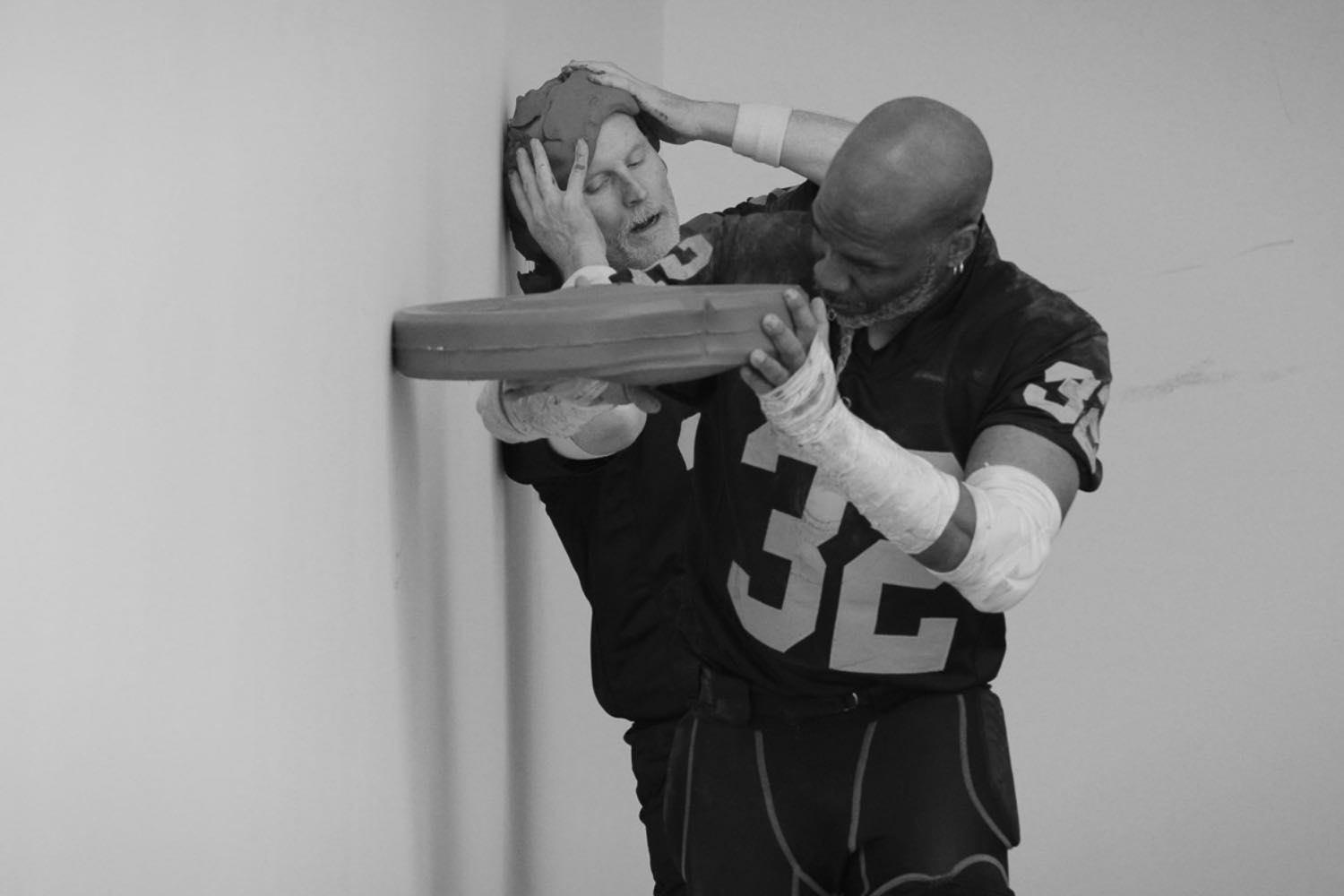

In the first room of the gallery, Thomas deploys his own body via malleable replicas that cohabitate with historical materials carefully sourced from construction sites in New England or the Internet to generate impossible environments. Untitled (2024), for instance, features a concrete cast of the artist’s frontal torso in the manner of attentive naturalism — scars from Thomas’s gender-affirming surgery are transferred with verisimilitude — on a steel structure with stained glass filling some of the negative space created by an intersecting web partially framed by bigger metal plates. The charred architectural structure appears to have endured fire, hence the state of incompleteness, or was never conceived to reference a functional original. The ambiguous dramatics of the tense body offer little clue about its movement in space. Thomas’s proxy could be falling from a roof or window of a Catholic church or being birthed out of the divine into the earthly. The interpretation is wholly situational, and the work only comes to fuller legibility in relation to other reproductions of the artist’s body, such as its more introspective counterpart installed across the room, in which two severed pieces of cast chest, the sites of nipple as hollowed apertures, fragilely attach to a structure of the same material that provides enclosure and connectivity. Charcoal lines behind index the work’s internal flow and serve as notional marks extending physical structures to imaginary territories.

Elsewhere, the body’s ambivalent entrapment can be felt in the monumental Untitled (2024), a found grandfather clock against a wall of steel roof shingles caught between impending collapse and rising momentum, with mica and silicon surgically stitched together inside the former locale of weight and pendulum, now transformed into a wounded belly.

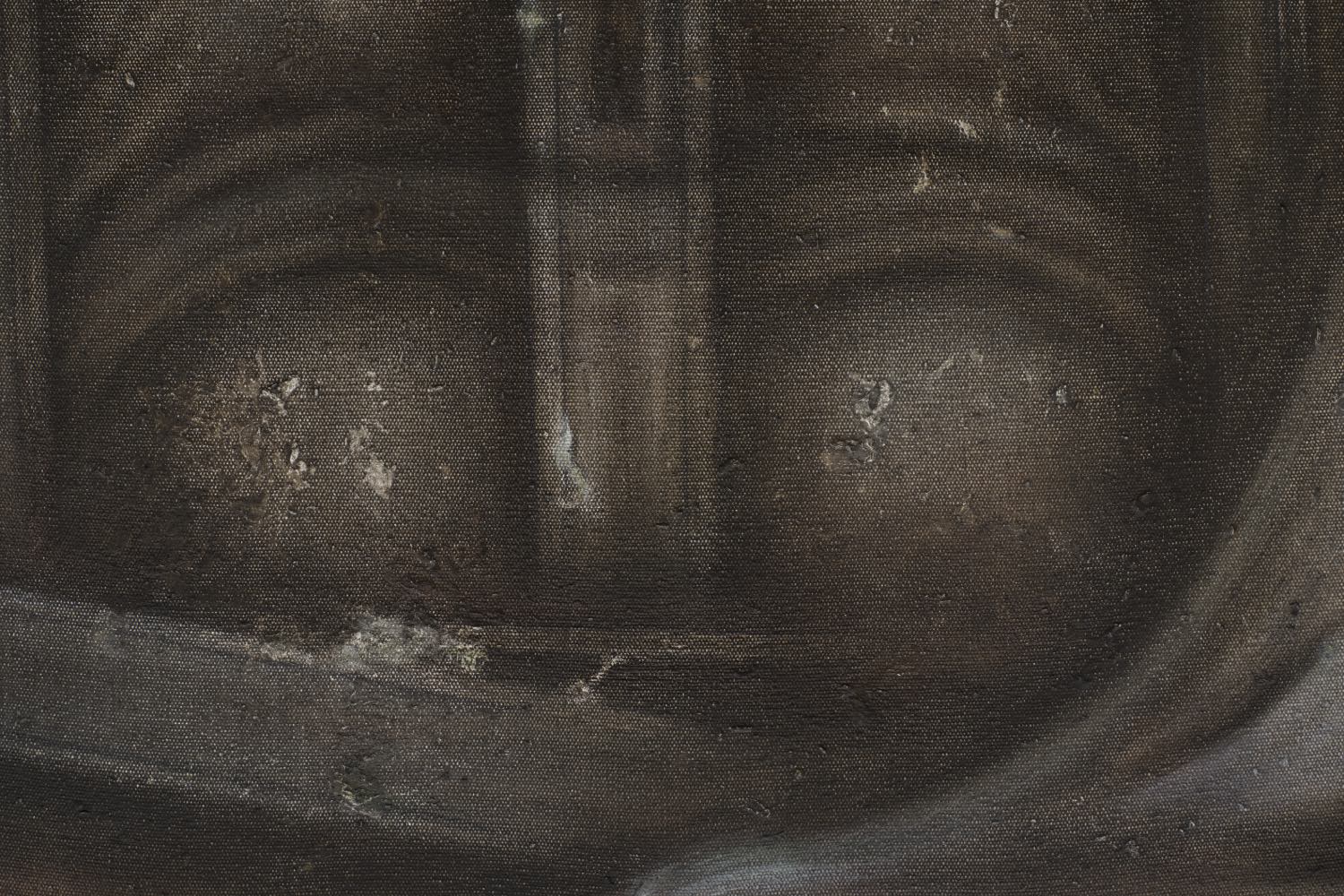

Positioned in the center of the second room, Untitled (2023–24) is an angelic figure in a kneeled-down position of humility or defeat — precise meaning again dependent on viewer projection — crushed by the weight of wings made from wooden colonial columns. In making the humanoid, Thomas intentionally allows for imperfect casting that liberally retains accidents of cracks and misalignments to construct a mythical effect of archeological decay. Like Thomas’s various face casts in the exhibition, the figure has no capacity for speech or vision, with only its back and buttocks visible. On both sides of the room, a colonial window frame slides against the wall, suggestive of a disrupted domestic setting that requires a working window to maintain an order of interiority. The stained glass adorning the window frame conveys no glory of spiritual devotion; rather, it takes on a feeling of organic opacity due to the artist’s insistence on using a mix of mica and silicon that simultaneously gestures toward the ornamental, the infrastructural, and the biological. In the far end of the room, a Romanesque alcove is repurposed to deny access to more space, while the space fenced off within seems to suffer from mystical leakage: a bronze cast of the artist’s feet grows from vaginal-shaped openings.

The third room houses Untitled (2024), a sprawling installation of rusted steel panels acting as wall surfaces. In a revisionist approach toward monumentality, the installation forbids viewers from entering the room and seals its other component, a flock of rusted cast resin feet, ranging from faithful recreations to sheer remnants, that cover the entire floor to form an unconcealed totality of pure grandiosity. Its signification is physically maintained by the doubled act of unmediated accumulation and consumption. Perhaps the component most committed to clarity in the exhibition, Thomas’s collection of resin feet remains strictly anonymous and impersonal despite its multiplying organization, harboring a quasi-religious affinity for the singular.