When Berlin Alexanderplatz was first broadcast on the WDR in Germany in December 1980, I watched the first episode as a 14-year-old in my parents’ living room. Televisions weren’t flat screens, plasma or high-definition flat panels in those days, but plain, big boxes with a cathode-ray tube that curved convexly into the room. In some of the early episodes we watched, we actually only saw the reflection of our living room, lit by a standard lamp, on the screen, which the dark picture had transformed into a mirror. My parents thought that the scenes we could see were too violent for the early pre-Christmas period, and starting with the second episode I watched the series on an old, discarded black-and-white television set in our cellar (in a completely darkened room, so that I could see better). So, for me Berlin Alexanderplatz has always been a black-and-white film.

Twenty-seven years later, Berlin Alexanderplatz has been restored, and with the technology available today the detailed picture structure and color nuances can be shown as Fassbinder originally conceived them. Sequences with resolution reminiscent of the translucency of watercolors are contrasted with opaque areas that look nearly like impasto. Soft color transitions, almost without outlines and sharp contrasts, occur in exactly the same way as settings composed from separate pictorial points. Linear episodes alternate with complex picture and sound collages that often involve different degrees of abstraction and various narrative levels. This extraordinary conception of form, especially in the pictorial sequences that Fassbinder invents very freely, leads to a quality suggesting an alienated, timeless world, almost caricatured, like a comic strip or fairy tale. Lettering and images of formulae alternate with moving images and stills that are faded in, and accelerations and rotations give way to almost stationary, very long shots.

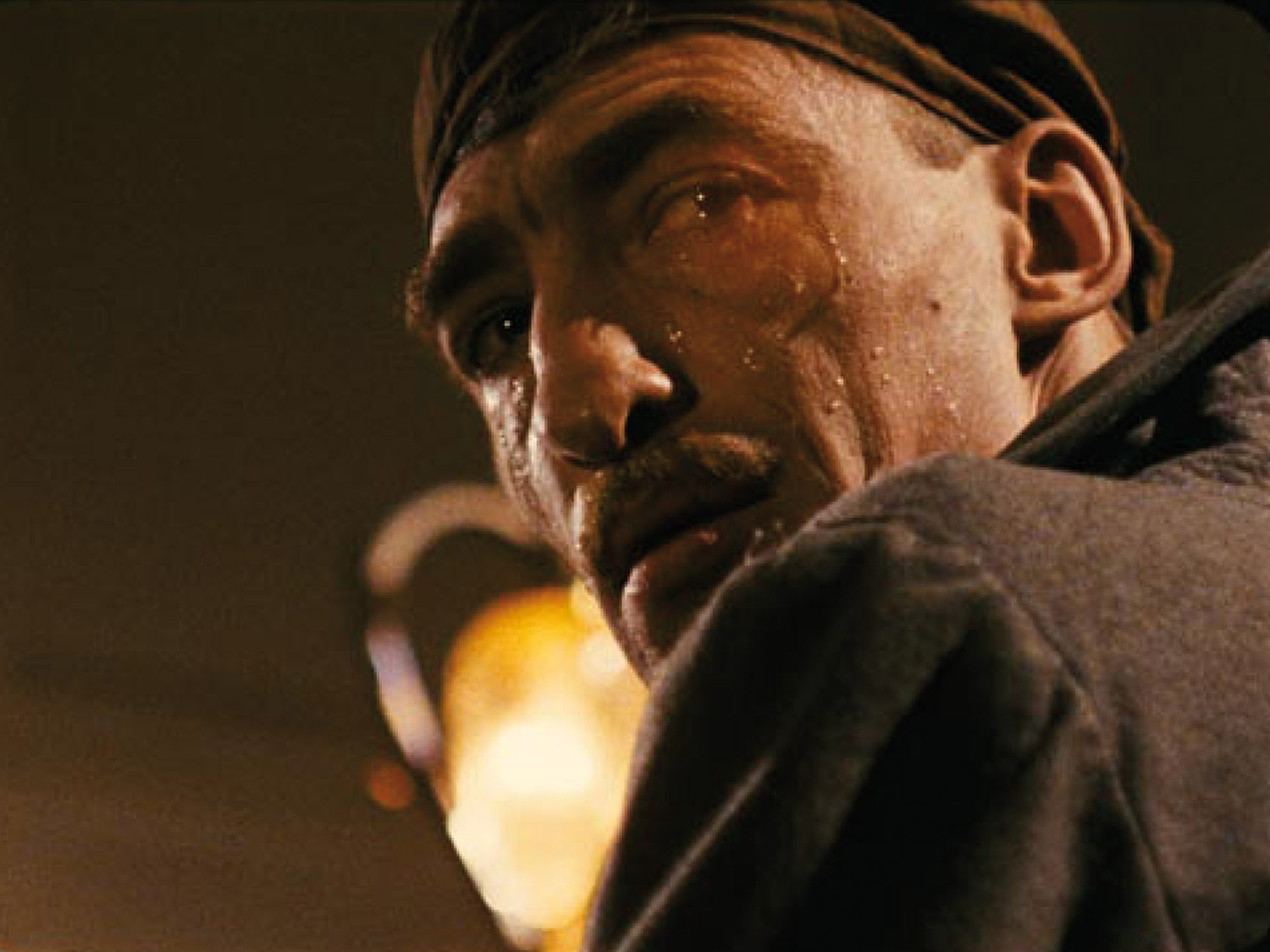

For financial reasons, Berlin Alexanderplatz was shot on traditional 16 mm film stock and televised from a positive copy, not even a negative. The television technology of the time alienated the lighting to a greater or lesser extent and made it almost impossible to transmit the material in a way that was faithful to the original. Like computer monitors, television screens are reflective, glowing surfaces; they radiate light into viewers’ faces, who can often see themselves reflected on the surface of the screen. But projections are matte images in which we cannot see ourselves reflected; the projected light is moving in the same direction as we are looking, almost as though it is extending our inner eye, our imaginations, our thoughts, and our dreams into the room. As a projected color, black is like a hole, a piece of non-information, a place on the film that is impermeable to light. Shades of darkness and the finer nuances of light and shadow can be presented more subtly. If it is raining at night and you look up through an umbrella at a street light, the moiré of the umbrella fabric creates a bright star with the light source at its centre. Light sources in Berlin Alexanderplatz often have a star-shaped aura of this kind. Candles, torches, ceiling lamps and candelabras exemplify this phenomenon as direct light sources, and so do lights reflected in mirrors, in sweat on faces or in the actors’ eyes. The disco balls used in several places and silver or gold glitter on hair have similarly radiant accompaniments. A bottle a character holds in his hand diffuses light and becomes a material-immaterial object made up of light. The light sources concentrate a powerful visual focus.

Fassbinder’s ambition to develop even the most minute detail of this film artistically and visually should have been argument enough against using 16 mm stock. In an interview with Juliane Lorenz, Fassbinder’s editor and director of the Rainer Werner Fassbinder Foundation, the cameraman Xaver Schwarzenberger mentioned that most of the scenes from Berlin Alexanderplatz were filmed with a silk stocking over the camera lens. A glance at the set photographs, taken by a photographer before and during the shooting of Berlin Alexanderplatz, reveal one of Fassbinder’s strategies for defining images. Long stretches of the film seem as though they have not been photographed in a straightforward manner, and the difference between set photographs, frozen stills, and the image on film is as vast as it is significant. In his play with light, contrast and focus, Fassbinder used artistic manipulation to heighten effects, especially in the treatment of light and spatial volumes, in a way that is characteristic to the whole film. Because the silk stocking did not create enough texture and structure in the image and did not transform enough light and spatial volume into material, Fassbinder also used mist in the woods or in the underground station. Reflective particles swirled around in the image, and these fill the space like a cloud of midges. He also hung rotating ceiling fans so low that the actors had to watch their heads if they made quick movements. Space is filled.

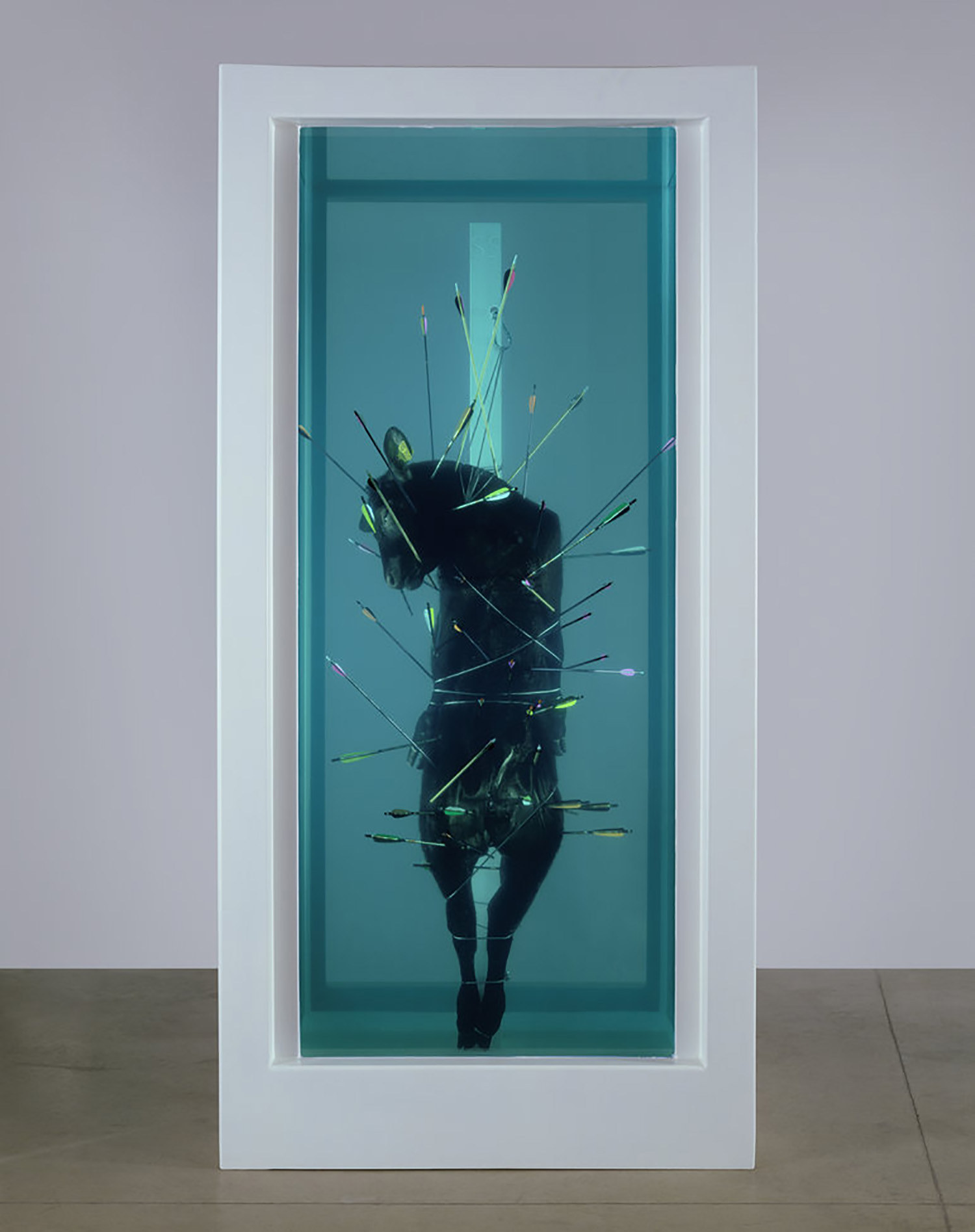

Like his model Douglas Sirk, Fassbinder loved views through windows or in a mirror as ways of structuring space in a film. But he goes much further in Berlin Alexanderplatz: his camera looks into the darkness, through stockings, etched panes of glass, curtains and aquariums. Based around this delight in experiment, in exploring creative and visual boundaries and constantly subjecting his images to new modes of alienation, Berlin Alexanderplatz and Fassbinder’s other films generally still have not ceased to influence today’s visual forms of construction. But the special interpenetration of fine art, theater, performance, music and literature Fassbinder experimented with seems to have made an impact on the exhibition canon of the great biennales and museums and thus on public awareness only in recent years. In fine art, projection formats, fades, collage and montage techniques have become something like the “golden frame” of the last 15 years in the context of moving images.

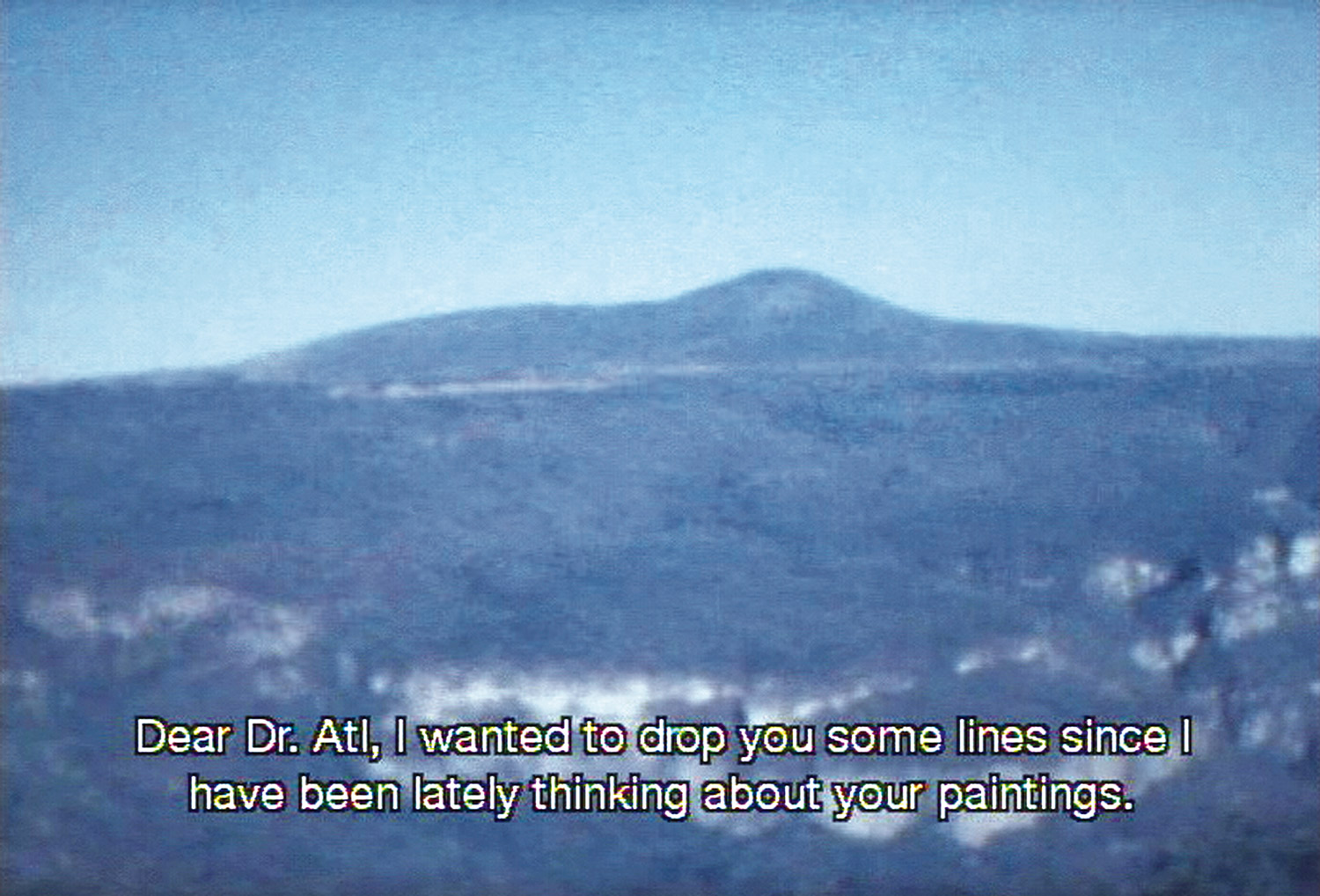

When I organized the 1st Berlin Biennale für Zeitgenössische Kunst in 1997-98, several works referred directly to Fassbinder. For example, a room installation by Johannes Kahrs contained sound elements from Fassbinder films, and there were also unmistakable references to Fassbinder in works by Jonathan Meese and Christoph Schlingensief. Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster had even quite explicitly reconstructed a Fassbinder bedroom. Ugo Rondinone’s video installation So Much Water, So Close to Home (1998) showed the first scene from Fassbinder’s Götter der Pest (1969) as a loop. Fassbinder’s work has become a point of reference and comparison for numerous contemporary artists, and in particular the epilogue to Berlin Alexanderplatz has a creative potential that now stands as a complex response in the dialogue with contemporary artistic practice. In Pina Bausch’s Die Klage der Kaiserin (1989) a remote-controlled helicopter flies in front of a dancer in a white dress. The helicopter flies high and low in the space, sometimes closer to the dancer and sometimes farther away. Its rotors spin like threatening knives that could tear the white dress or the performer herself to pieces at any time. This fascinating spatial tension, defined by the presence of a human body and a wind-producing machine, is described similarly with the countless fans Fassbinder uses to fill his spaces in Berlin Alexanderplatz. In Kring (Circle) (1992), Marijke van Warmerdam and her camera spin around a crowd of people in a circle, and she presents this footage with a projector rotating on a plinth. The Long Count (2001) by Paul Pfeiffer depicts a boxing ring astonishingly similar to the boxing ring where the two protagonists of Berlin Alexanderplatz finally confront each other. In Pfeiffer’s work light seems material on the digital surface, and the division between spectator and boxer, presence and non-presence, is manipulated. In his media-reflecting works, Pfeiffer appropriates major themes and motifs from sports, cinema, history or religion. In certain works he relates directly to figures in painting like Francis Bacon, for example, and shows how close his work is to painting as a surface and medium by pixelating his video images. While Bausch’s, Van Warmerdam’s and Pfeiffer’s works may share merely formal parallels with Fassbinder’s motifs, Jeff Wall’s The Destroyed Room (1978) can possibly be read as a more direct and explicit reference to Fassbinder. The same applies to Cathouse (1997), an early video work by Doug Aitken, in which the artist conveys his understanding of space and dialogue in Fassbinder’s work. Another example is Douglas Gordon’s Fassbinder mirror, which is installed so that it seems to deepen space; it permits an inside or outside perspective according to viewpoint, referring directly to how the eye is guided in Fassbinder’s work. In Runa Islam’s installation Tuin (Garden) (1998) the artist runs a remake of a short sequence from Fassbinder’s Martha (1974) in a loop. And even when we look at Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980) today, we immediately associate some of these photographs with Fassbinder’s pictorial world, which has become such an integral part of collective memory.

It was clear relatively early in the planning phase of Berlin Alexanderplatz that the aim was a highly demanding approach, as concentrated as it was rapid, often with only one take per shot. As many of the scenes were shot only once, it was almost like working in theater: the actors had to play their parts and immerse themselves in character without a second chance. This blurs the boundaries between acting and performance: Mieze’s bloodcurdling scream in the tenth episode of Berlin Alexanderplatz, like a short, intensely overdawn version of Marina Abramovic’s 1975 Freeing the Voice action, functions as a performance.

Even the extreme duration of the film seems more appropriate as a device for special artistic expression in our present age of short attention spans. One has only to think of Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle (1995-2002), which runs for 11 hours. Warhol’s eight-hour film Empire (1964) reveals the proud symbol of New York as a phallic presence, while in over 15 hours of Berlin Alexanderplatz we see only a void or omission, rather than its namesake, the central square scarred by history. Fassbinder could not shoot in historical locations, not just because they were in East Berlin, but because they no longer existed in the same form.

Fassbinder influenced contemporary pictorial strategies, but the nearly black images in Berlin Alexanderplatz also parallel such works by early artist-figures as Francisco de Goya’s Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra, 1810-1823). Toward the end of his life, when absolutist power in Spain was restored again, Goya withdrew into the country for a few years before going into exile in France. From 1820 to 1823 he produced the Black Paintings (Pinturas Negras) directly onto the walls of his country house Quinta del Sordo near Madrid. As in the production of his late miniature paintings on ivory (1824-1825), this hermetic impulse, the concealment of the artist in his own darkness, presents man as inseparable from the environment that surrounds him. In the Black Paintings, figures group around light sources or are only visible in close proximity to that light. The seemingly tangible picture surface, miserable subjects, surrounding objects and dark background form a tactile, homogeneously flat yet simultaneously deep plane. As Goya painted the Black Paintings not long before his death, they are intermediaries between past and future catastrophe. From today’s perspective, 1920s Berlin is seen both as a post-war and a pre-war period. Alfred Döblin’s novel Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929), which the film is based on, processes the traumas of the First World War as much as he projects them forward, while almost seismographically detecting and recording the signs of a new impending disaster.

Almost three decades after it was completed, Berlin Alexanderplatz has not lost any of its explosive force. It is remarkable how many visual strategies and experiments Fassbinder anticipated, especially in his epilogue. His epic work pushes at the outermost borders of film language and creates a visual world that has a considerable closeness to current art production.