In 1969, Betty Tompkins (b. 1945, USA; lives in New York and Mount Pleasant, PA) began her series of “Fuck Paintings,” based on foreign pornographic images imported by her then-husband. Interested in the tension between the abstract and figurative qualities of these images, Tompkins began gridding them and transferring them onto canvas via airbrush. She was uninterested in how these works might be received because, for women artists, no one was paying attention anyway. Perhaps, in a perverse way, sexism was a blessing, because it allowed for an explosion of female creativity in the face of an oppressive patriarchal regime. When two of the paintings were slated for exhibition in Paris in 1973, they were detained at customs for their subject matter. Tompkins even had a dealer sheepishly back out of her studio upon entering a swirling realm of disturbingly realistic genitalia that were nevertheless expressive and large enough to elicit art historical fury at the perceived bastardization of Abstract Expressionism’s legacy.

Parallel to these art historical reservations were thematic questions that brewed as the feminist movement championed positive depictions of the female body, such as Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s 1971 founding of the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts, as well as the 1974–79 creation of the monumental The Dinner Party, a celebration of women’s history through a specifically female-bodied lineage of vaginal place settings. It seems, moreover, that Tompkins prefigured the bitter feminist sex wars that would re-route some feminist thought toward media representation of women, resulting in a raging battle against sexual depictions deemed to be objectifying. One can only imagine the scene that would ensue if Catherine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin made their way into Tompkins’s studio.

There is little doubt that Tompkins’s career could fill an entire volume on feminist imagery and body politics. However, as is often the case with minority artists, critics and historians collapse the complexity of the artistic act into subject matter, most notably the work of queer artists, male and female, during the AIDS era. Art made by women becomes necessarily and solely about feminist activism (or worse, some essentialist archetype of women’s work, as was the case with Ken Johnson’s review in The New York Times of Michelle Grabner’s recent show at James Cohan Gallery), and queer individuals must always make art that is about non-normative sexuality. There is thus no room for minority individuals to substantively rework the dominant art historical narrative; their contributions are instead begrudgingly integrated only because they are forcefully marked as perpetually different. Why is it that, for instance, we rarely discuss Marilyn Minter’s work in terms of its masterful process of layering, its distancing and cross-disciplinary nature — descriptions that could also be applied to Tompkins? Minter is only allowed to exist in the separate and gendered world of fashion, instead of, say, the history of Surrealism with its fascination for the sullied, disconnected body.

It is for this reason that Tompkins deserves to be positioned as both a pioneer of sexually progressive work, but also of formally replete engagements with appropriation, photorealism and abstraction. In fact, for Tompkins, identity politics and the medium are as intimately connected as the scenes she depicts. She hopes to “get content and the formal elements of the painting locked in an equal and eternal battle,” amounting to what I would tentatively deem a feminist formalism.[Email correspondence with the artist, 14 June, 2015]. Tompkins thus exhibits a simultaneous engagement with body politics and the politics of paint itself, which is to say that issues of gender are integrated into the very level of making, rather than solely manifest in her chosen themes or subject matter — as is often assumed of female artists. It is my hope to interrogate the multitude of ways in which gender and sexuality can be expressed, with full respect to the importance of feminist imagery and its necessary role in art history.

The first such site of inquiry is Tompkins’s relationship to appropriation. While her early “Fuck Paintings” are based on real, tangible pornography, Tompkins refuses to leave the image untouched. She crops, rotates and even changes the physical characteristics of her “actors,” all in an effort to zero in on a single moment that hovers between reality and abstraction. Take Fuck Painting #7, in which coitus becomes reduced to a (sexual, or perhaps entirely platonic) mingling of brushstrokes, a fact that is only intensified as a result of the hazy, atmospheric airbrush technique. Close examination of the “Fuck Paintings” leaves one with the joy of being confronted with an image of limitless visual possibilities, all drawn from an original photograph that we will never be able to see in its true fullness. Tompkins choses the world she wants us to see.

Tompkins’s appropriation strategy, which informs her categorization as a photorealist, is more than a blind sampling of culture; each image is carefully selected and manipulated according to her unique vision. This puts her in communication with artists like the late Sarah Charlesworth, who, in her “Modern History” series, removed all the text (save the header) from newspaper front pages, thereby exploring possibilities for creating a subjective relationship among and with images that are otherwise staid in their industrially produced silence. Tompkins makes her material sing anew — formally and thematically; a transubstantiation of medium and meaning occurs that, in its fearless collision with normative culture through crops and alteration, becomes a feminist act, an exemplar of female agency in a sea of high capitalist consumerism that would otherwise deny it. With this adroit relationship to images, Tompkins is thus as much a Dadaist as she is a feminist; the two strands of her work commingle and produce heretofore-unexplored spaces for reflection upon identity, causing one to understand the true nuance of art informed by gender and sexuality. The “Fuck Paintings” transcend, but still remain inextricably connected to, subject matter.

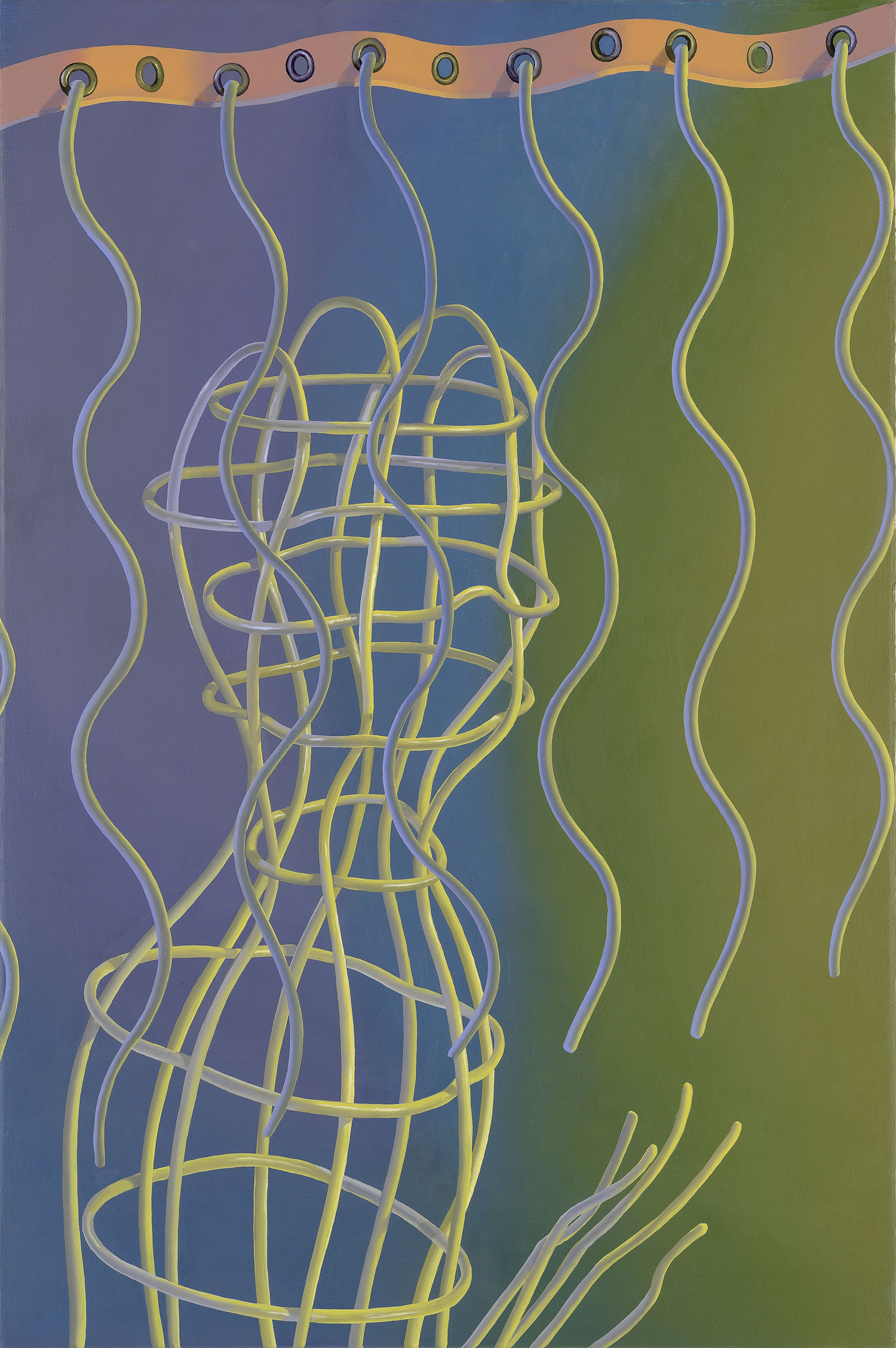

Central to Tompkins’s paintings and drawings is a dedication to the grid, which is readily apparent in drawings such as Censored Grid #1 (1974) and Censored Grid #5 (1975), one of which cheekily redacts the genitalia; the other highlights them. Chuck Close would be an obvious counterpart, but the importance of the grid runs even deeper in Tompkins’s paintings; the grid is occluded but nevertheless operative. It is intentionally hidden in her paintings, but its presence is doubtlessly felt, as its organizing function allows Tompkins to achieve a simultaneously structured and lively realism that she calls “the coolness of the process.” [Ibid.] As a result of the grid’s presence, there is a collision between the corporeal and the artificial — the grid being representative of all that is not found in nature — that is important to Tompkins’s work. She becomes, perhaps, a dirtier Agnes Martin.

Central to Tompkins’s paintings and drawings is a dedication to the grid, which is readily apparent in drawings such as Censored Grid #1 (1974) and Censored Grid #5 (1975), one of which cheekily redacts the genitalia; the other highlights them. Chuck Close would be an obvious counterpart, but the importance of the grid runs even deeper in Tompkins’s paintings; the grid is occluded but nevertheless operative. It is intentionally hidden in her paintings, but its presence is doubtlessly felt, as its organizing function allows Tompkins to achieve a simultaneously structured and lively realism that she calls “the coolness of the process.” [Ibid.] As a result of the grid’s presence, there is a collision between the corporeal and the artificial — the grid being representative of all that is not found in nature — that is important to Tompkins’s work. She becomes, perhaps, a dirtier Agnes Martin.

This is not unlike Piero Manzoni’s famous Achrome with Bread Rolls (1961), in which the artist covered real bread rolls with kaolin and affixed them in a five-by-five gridded pattern. The monochrome (which Tompkins nearly approaches in her early work) and the grid come together momentarily, but their union is disrupted by the bodily rolls, which, according to Jaleh Mansoor, “literally [well] up as embodied figure and visually [withdraw] as support” [“Piero Manzoni: ‘We Want to Organicize Disintegration,’” October 95 (Winter, 2001), pp. 28–53]. The bread rolls, stand-ins for the unpredictability of human subjectivity, disrupt the grid, even as they are swallowed by its all-encompassing presence. This same interaction between abstraction and realism, the body and the technocratic, occurs between Tompkins’s unpredictable and subtle coitus-turned-abstraction, as well as her chosen process of transference among skin, the photograph and her canvas. A similar operation is at work in Jasper Johns’s Target with Plaster Casts (1955), in which Johns creates actual replicas of interrelated body parts that are mercilessly (or beautifully) divided by the grid. This history doubtless on her mind, for Tompkins, the grid is a generative tool that allows her to take on many roles — Abstract Expressionist, Photorealist, modernist, postmodernist and feminist, with no moniker taking precedence. This chameleon quality has continued into the present. After leaving the “Fuck Paintings” behind for some time, Tompkins picked up her airbrush once again to return to what could be considered her magnum opus. Now using colorful under-painting, the “Fuck Paintings” have taken on an entirely new life that will only evolve over time.