The advent and proliferation of technologies that encourage practices of accumulating and storing information has precipitated a contemporary preoccupation with the archive. This archival fixation is no stranger among the art world, in which artists, art historians, and curators look to records of all kinds as sites of potential. Baseera Khan’s solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum — awarded through the UOVO Art Prize and curated by Carmen Hermo — offers a unique and capacious approach to archival practices. Titled “I Am an Archive,” Khan asserts that, like the museum itself, they, too, are a font of knowledge. Khan’s multifaceted practice, which incorporates an almost endless array of media, mirrors the multiple and complex experiences and traumas their body holds.

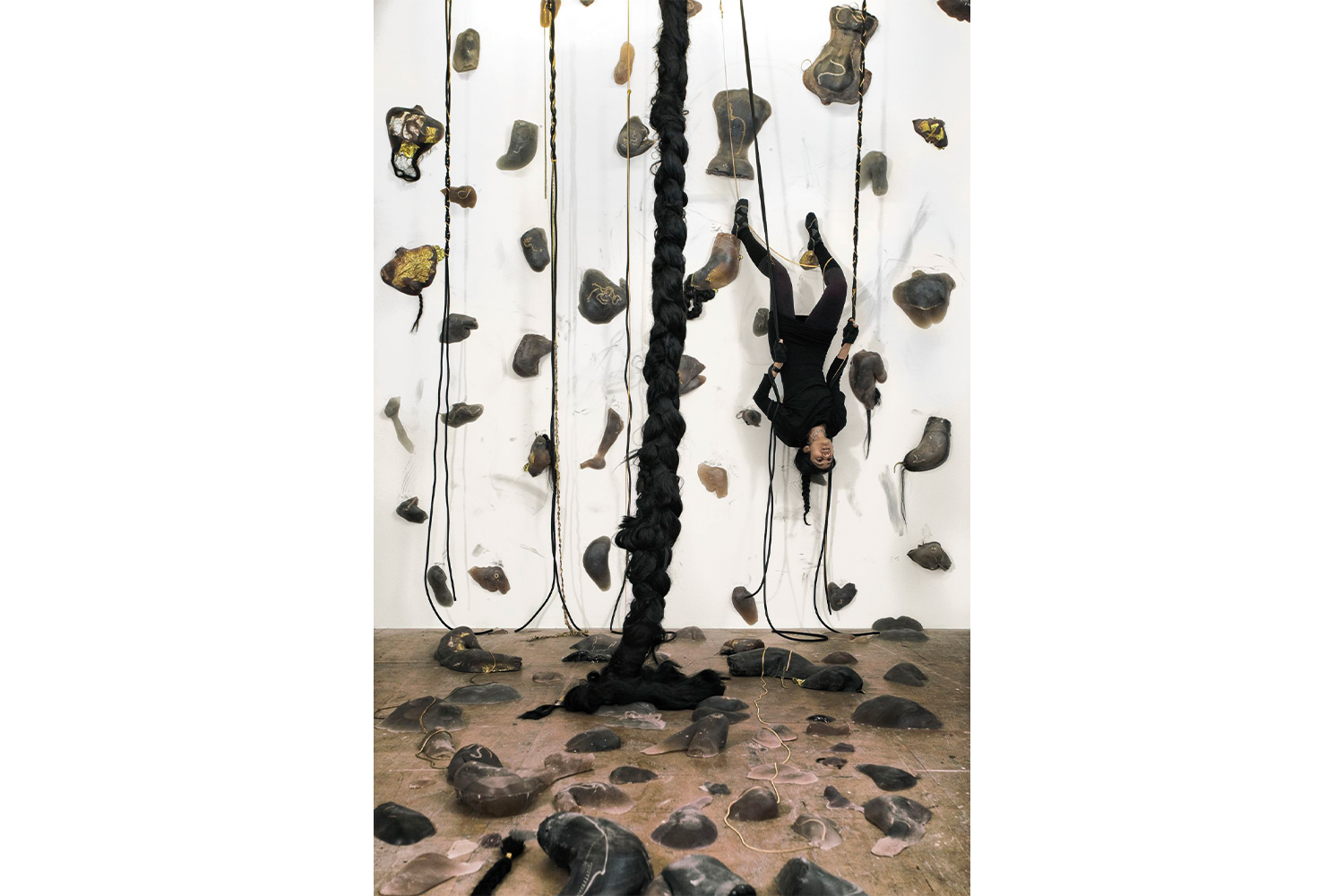

When you enter the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, you are greeted first by sound. As if creating four new bodies of work for the show were not impressive enough, Khan, along with Kaia Fischer and Stuart Gunter, wrote and performed an eleven-song album that reverberates throughout the galleries. The center of the first wing remains almost entirely clear, shining metaphoric (and literal) spotlights on four hanging chandeliers. These objects, made primarily of mirror-like, jewel-toned acrylic — a petroleum product — address negative stereotypes associated with oil-rich, Muslim- majority countries. Each chandelier is patterned differently, sourced from Khan’s family archive of Islamic Arab and South Asian textile and embroidery designs. As these pendant sculptures rotate, flashes of light swirl along the walls, reminiscent of disco ball reflections and moments of festive gathering that continue to feel foreign in the pandemic. The entire exhibition reflects this elegant dance through its delicate balance of dichotomies, including the personal and political, past and present.

Khan’s new series, “Bust of Canons” (2021), brings contemporary surveillance techniques and social media culture into conversation with temple sculptures of Hindu goddesses and deities. In “I Am an Archive, Speaker,” an unnaturally contorted, 3D-printed acrylic bust bursts open from its heart chakra. Amid resounding song, this figure, unlike the historical statues referenced in the work, is anything but silent. Khan compares the unrealistic beauty standards exemplified by idealized sculptures of South Asian women’s bodies with those of applications like Instagram. The bust is painted in a kaleidoscope of colors that dialogues with the chandelier works and speaks to notions of desire, play, and unboundedness.

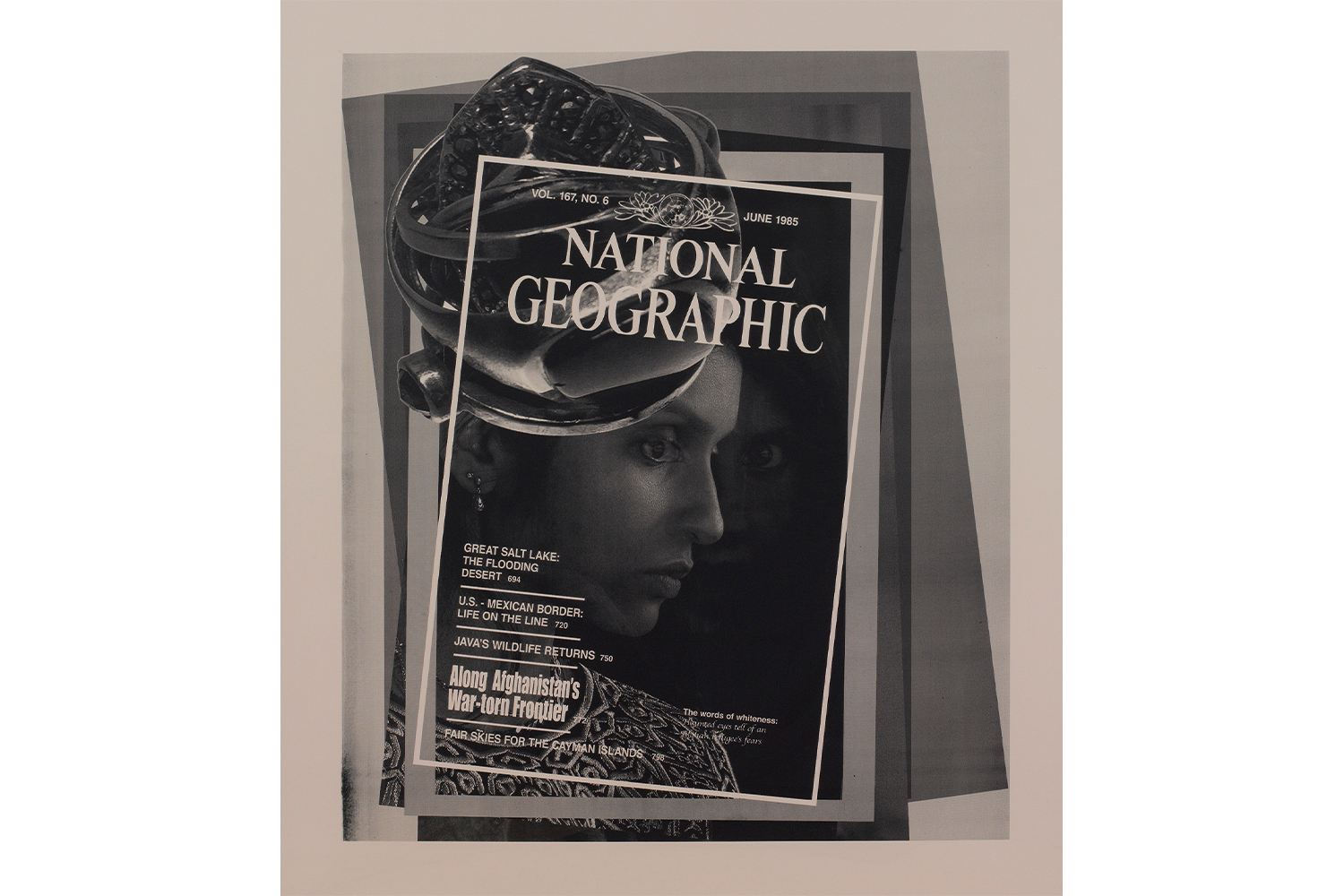

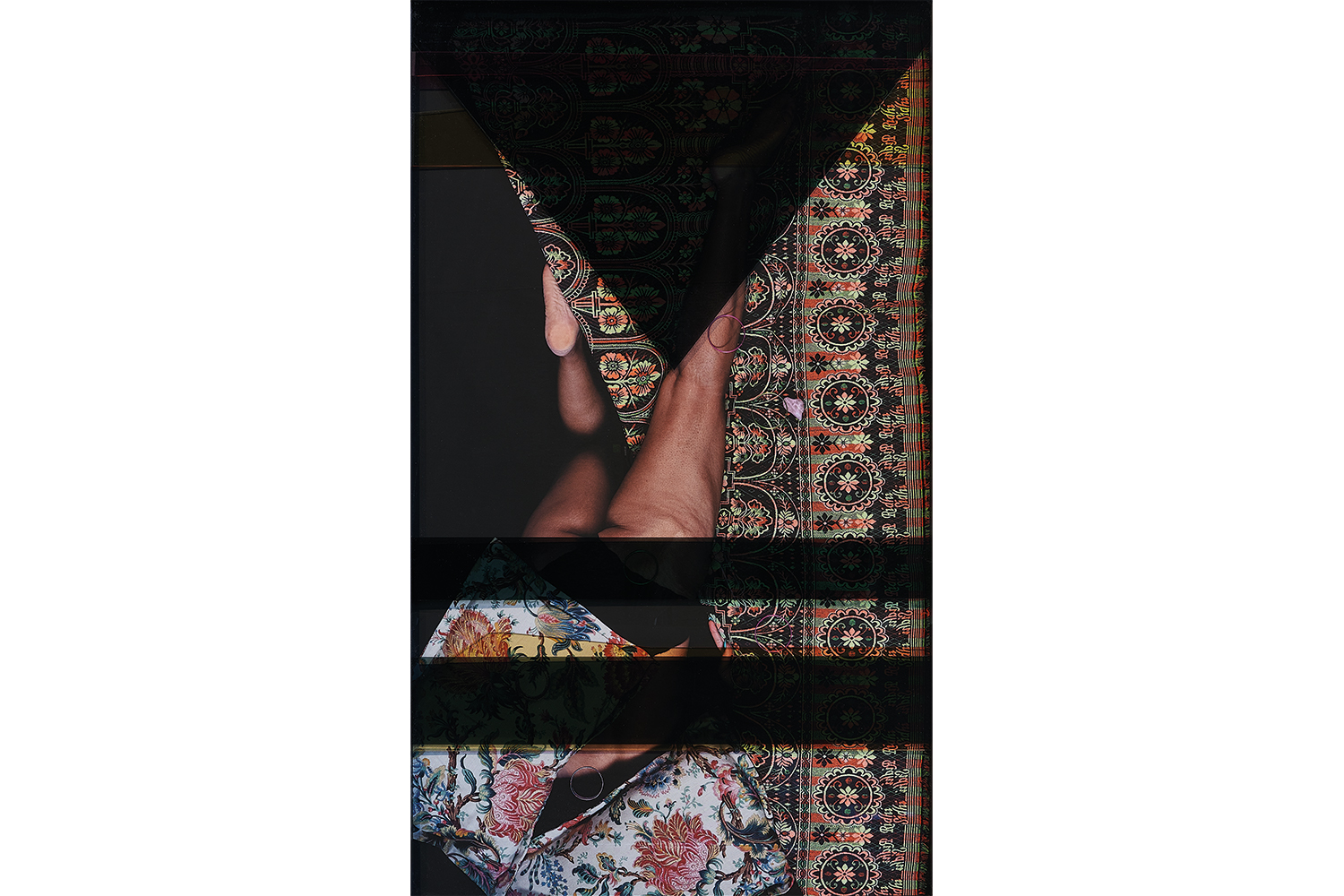

n the second wing, we encounter Khan’s new “Law of Antiquities” series, for which they collaborated with Brooklyn Museum curators and conservators to conduct interventions with objects from the Arts of the Islamic World collection. Staged in the museum’s photography studio, these collaged images are performance pieces and sculptural objects. Khan uses lime green and vibrant pink backdrops, which, in Jingle Johnny Processional Stand Pink (2021), for example, starkly contrast an old black-and-white cataloguing image of an Ottoman-era processional stand. Khan also highlights their brightly manicured hands. Along with their use of carabiners to provide structural support to the chandeliers and their inclusion of layered chain necklaces in several works, Khan brings aspects of queer and femme aesthetics to center stage. Even the nitrile gloves worn by those handling collection objects get a manicure. Khan seamlessly blends historical and contemporary, manipulating the museum’s archive to gain newfound control over its narrative.

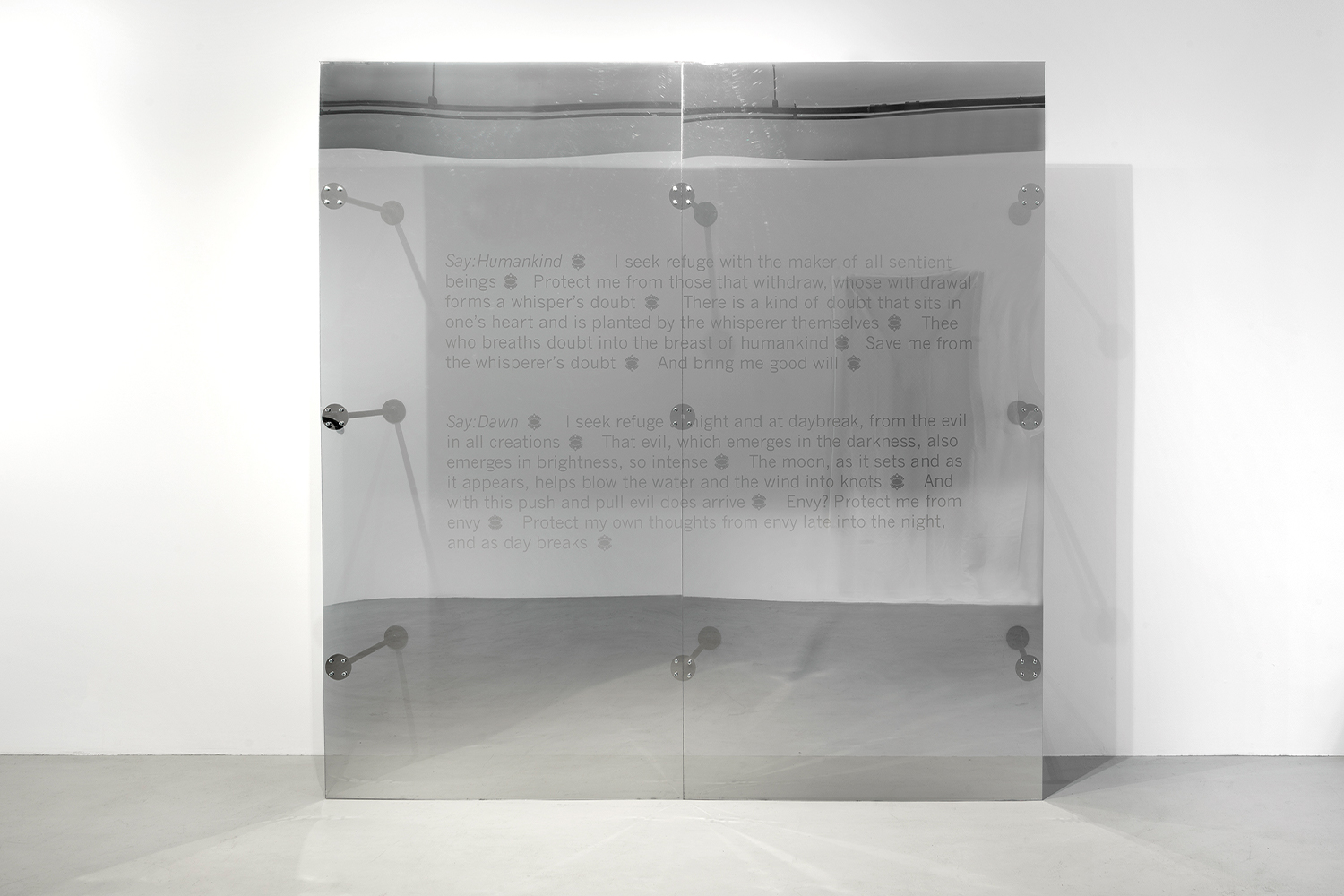

The final section brings the audience into intimate contact with the artist’s body and mind. In the Reading Room — inaugurated as a programming and community space in conjunction with the exhibition “Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall” (2019) — Khan includes copies of texts that inspire their research and practice and invites visitors to read these books and interact through marginal notes and comments in reaction to previous annotations. Khan hopes these acts of collective exchange might allow us to dream of possibilities outside current power structures, and to add to the living archive of their work.